*See more here

Imagine a world where police no longer needed human witnesses. One where they could determine that, while inside your home, you walked exactly 453m between 9.18am and 10.05am? Or perhaps they could prove that you’re lying, since they have medical records reflecting your cardiac rhythms during a specific timeframe? These are actual cases where police in the US traced minute details of people’s lives through their smart devices. In the former, a woman’s Fitbit proved her husband lied about her movements on the morning of her murder. In the latter, a man’s pacemaker gave him away in an arson investigation.

This is what evidence will increasingly look like as we move towards the world of 5G, where smart homes and cities become the norm. While 2G and 3G are still the most widely available networks in South Africa, cities are already changing. Since 2019, Rain, Vodacom and MTN have all launched 5G networks.

To see the drastic impact of 5G on government surveillance, it helps to take a step back.

The size of a briefcase

In 1979 in Japan, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) introduced the world’s first commercial cellular phone network in Tokyo. This was the start: first-generation – or 1G – cellular phones. By 1984, the 1G car phone service was available throughout Japan. But it was a niche product for the wealthy. Signing up cost $2,000 (about $7,200 or R110,000 today). Then, you had to rent a phone for$300 a month (just over $1,080 or R16,000 today). On top of that, calls cost $1 a minute ($3.60 or R54 today). You could get one to carry around too: the size of a briefcase, it weighed about 10kg.

1G only allowed voice calls. With a radio scanner, a spy could tune into conversations as if they were radio programmes.

Since the birth of 1G, a new generation of mobile technology has emerged roughly every 10 years (hence the abbreviations 2G, 3G, 4G, and 5G). Starting with 2G in 1991, there was a major change that had a lasting impact on surveillance: communications became digitised. With that came encryption – a mechanism to scramble a communications signal so that the message is incomprehensible to an eavesdropper.

There was also a lot more to intercept. Along with better call quality came texting with Short Message Service (SMS) and audio- and video-sharing with Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS). In 2001, 3G brought internet connection to phones. Spies could now also get hold of emails and browsing habits.

With 4G, the use of smartphone apps became entrenched. Apps collect masses of data about their users. Consequently, government agencies have access to a new form of mass surveillance. For instance, they now buy location data harvested from apps we install on our smartphones. In November 2020, Vice reported that the US military was purchasing location data taken from several ordinary smartphone apps, including a Muslim prayer app downloaded by 98 million people.

But with 5G, the amount of data that authorities can intercept will vastly increase, simply because the new standard is capable of so much more.

A major change with 5G, is how fast data downloads from the internet. 4G can download at a maximum speed of around 150 megabits per second (Mbps). Download speeds for 5G range from one to 10 gigabits per second.

Another defining feature of 5G is latency, and it’s measured in milliseconds (ms). Roughly speaking, it’s how fast data is sent from your computer or smartphone to a destination device (like Facebook’s server), plus the time it takes for that device to process your data. For example, if you update your Facebook status, latency is the time taken from the moment you click “post” to when your post appears on your wall.

Whereas 4G’s latency is around 45ms, 5G latency could, in theory, be as low as 1ms. You don’t need 5G’s low latency for gaming or streaming movies. But when you need hundreds of machines in a megafactory to talk to each other and react instantaneously, you do. It’s also vital to applications like self-driving cars and remote robotic surgery.

Whereas previous generations were all about connecting people, 5G is all about connecting machines. Entire cities and homes are set to become dependent on 5G simply to function.

Billions of devices

But one change accompanying 5G expansion is expected to have major implications for surveillance: the proliferation of the Internet of Things (IoT). The term refers to everyday appliances with computing power that collect data (through sensors, microphones, or cameras) and send and receive data via the internet. They’re also known as smart devices. Smart TV’s, smartphones and smartwatches are common examples.

IoT devices aren’t new. In 2000, LG introduced the first internet-based smart refrigerator. You could use it to send emails, take photos, or order groceries online. But at $20,000 per fridge, the idea never took off.

Yet by 2018, according to Statista, there were 22 billion IoT devices connected globally.

With 5G the number of IoT devices will vastly increase, since 5G has a much greater capacity than preceding generations. The International Telecommunication Union predicts there could be as many as 50 billion devices connected to the internet come 2025, with the amount of data traffic estimated to increase between 10 and 100 times from 2020 to 2030.

With so much more data, these IoT devices will give governments a new surveillance resource. In fact, they’re already making use of it.

Intimate personal details

Take, for instance, a voice controller – a speaker with microphones that receive vocal commands. Prominent examples are Amazon Echo and Google Nest, and they’ve been around since the mid-2010s. Police investigators are increasingly approaching the two tech giants for customer data.

A voice controller (aka a smart speaker) collects intimate details. It recognises your voice, and it “listens” actively in case you command it to switch on the lights, lock the doors, or schedule reminders. You can synchronise it with your smartphone’s contacts and issue a voice command to initiate a hands-free call. Amazon’s new Echo Show 10 has a camera that “follows” you around.

Another example that’s been around since 2012 and is popular with police in the US, is the smart doorbell. Ring, a company owned by Amazon, offers a smart doorbell that connects to your home’s wifi network. It’s fitted with a video camera, and you can use your smartphone to see who is knocking at your door. It records video whenever its motion sensors are triggered, and sends alerts to your phone. Recorded footage is stored on Amazon’s servers. In 2019 The Washington Post reported that Ring joined forces with 400 US police agencies to engage customers in sharing footage to assist investigations (much to the chagrin of civil liberties organisations).

Then there are smart devices that police haven’t taken a fancy to (yet). But, if they did, a social robot for home entertainment captures a lot of intimate data. With sensors, an HD camera, microphones and speakers, it automatically navigates its way around your house, while it plays music and takes snapshots of your daily activities.

Information won’t just be generated in your home. If two driverless cars crashed, data collected by their sensors or cameras could reveal detailed information about the accident. Police could also give up blockades and simply pull smart cars over by taking control of them remotely. According to Professor Elizabeth Joh of the Davis School of Law at the University of California, “Autonomous cars are not yet commonplace, but soon they will be. Yet little attention has been paid to how autonomous cars will change policing. Vehicles equipped with artificial intelligence and connected both to the internet and one another may be subject to automated stops. The issue is already being discussed as a theoretical possibility and as a desirable policing tool.”

Burgeoning field

Along with increased data generation, the digital forensics field has burgeoned, according to a review paper from Interpol. The growth of smart technology and apps is a major factor driving this expansion. The global digital forensics market will be worth $9.68-billion come 2022, according to MarketsandMarkets. Behind the increase are tougher government regulations, escalating cyberattacks, and mass adoption of IoT devices.

Also trending upward: police’s reliance on smart devices as a source of evidence. There was a steady increase in police requests for Google Nest data from 2015 to 2018, but after that Google stopped issuing separate statistics for cops’ Nest data applications. Amazon doesn’t issue separate statistics for police requests of IoT data either, but 2020 saw the highest number of police applications yet – some 3,105 from January to June. That’s up 24% compared to the same period in 2019. Experts suggest that the increasing number of smart devices is contributing to this trend.

IoT devices have featured in some serious criminal cases. Fitbits, smart watches, and voice controllers have provided evidence in rape and murder investigations in Europe, Australia and the US. But how police use IoT devices to investigate brings “new challenges and risks”, says civil liberties group Privacy International. The organisation warns that laws are outdated, and people lack awareness of the data that IoT devices generate.

South Africa

That lack of awareness stems partly from the fact that data generated and transmitted by smart devices can be stored in a variety of formats and places. Formats include audio, video or any other data file depending on the device’s purpose. Data could be on the device itself, on company servers, or on the smartphone used to control the device.

That means if police in South Africa want data related to a smart device, they’ll need multiple subpoena laws.

To learn more about the local context, Daily Maverick spoke to digital forensic specialist Peter Fryer. He’s spent two decades in the field, working with the South African Police Service (SAPS) on cybercrime investigations, delivering expert testimony, and training police in the Southern African Development Community in digital forensics, evidence handling and first responder protocols.

Fryer said the SAPS hasn’t started making use of smart devices in investigations yet, since too few people use them. But if police wanted to get hold of smart device data stored on servers in the US by tech giants like Amazon, Google or Facebook, they’d use the mutual legal assistance treaty (MLAT) between SA and the US. It’s a legal framework through which two countries assist each other in criminal investigations.

These US tech companies distinguish between two data types: content and non-content. The former includes items like emails, WhatsApp messages, and social media posts (for instance, what you wrote on your Facebook wall). With smart devices, content can include photos, visual and audio recordings, and biometric information (in the case of body-worn devices).

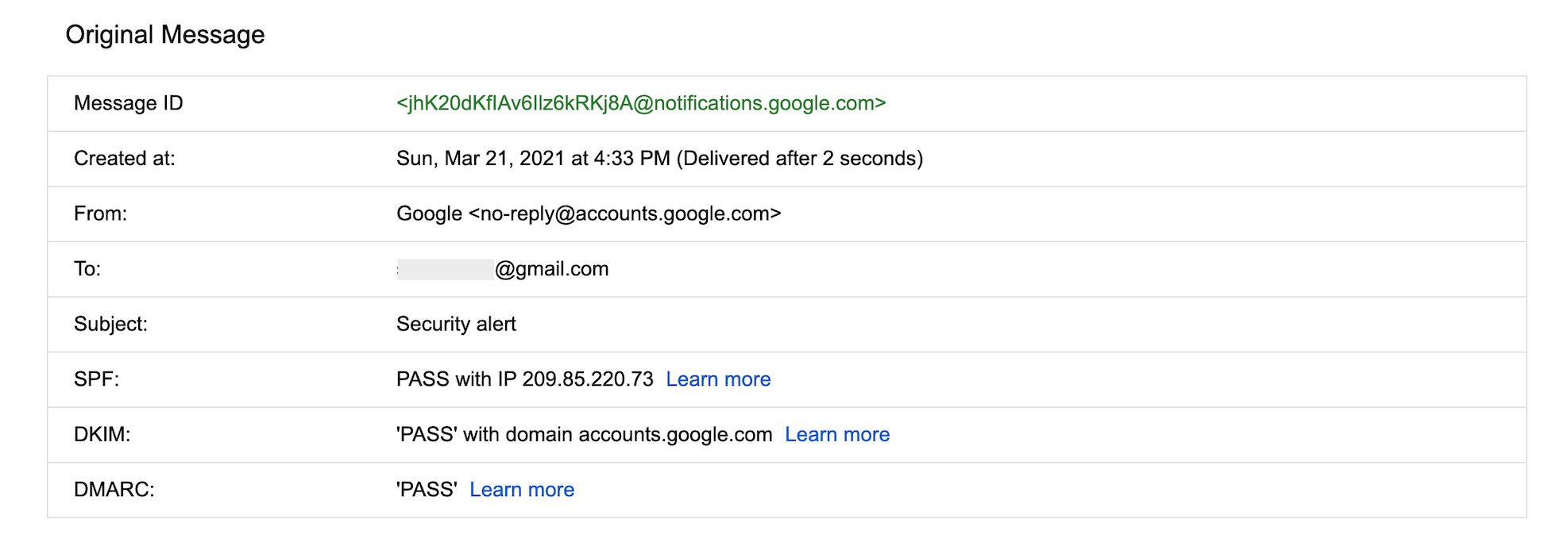

Non-content information includes data about your account and device. It includes subscriber registration information (like your name, surname, phone number, email and physical address), billing information, the date you created your account, and the times your device connected to the net. Police can also request your device’s Internet Protocol (IP) address – a unique number assigned to every device connected to the internet. An email header can also be disclosed. This includes the subject line, email addresses of the sender and all receivers, the email’s time-stamp, and the sender’s IP address.

Here’s an example of an email header in Gmail:

‘An arduous process’

But convincing companies to hand over information is a tough sell.

“It’s an arduous process,” says Fryer. “It can take weeks or months – you almost have to prove your case upfront.” He describes the procedure SAPS must follow (via the US-SA MLAT): First, they’d have to approach SA’s National Prosecuting Authority (NPA). The NPA would draft the request for information, which then goes to the US embassy. Here, the US State Department staff designated to deal with law enforcement examine the request, and then passes it on to the US Department of Justice, which then approaches the tech company.

Fryer says police’s motivation must satisfy South African and foreign legislation. He says tech giants have “robust and mature law enforcement liaison” staff that understand the law, but also know they must protect users’ privacy. Google, for instance, evaluates requests in terms of US laws, the law of the foreign country, the Global Network Initiative’s Principles on Freedom of Expression and Privacy, and its own policies.

Fryer says requests must be specific: “It can’t be a blanket application, like ‘I want the identity of everybody that tweeted #zumamustfall’. You have to approach it on a case-by-case basis. You have to show that the user you are making the inquiry about is actually in South Africa, that the suspicious act was committed in South Africa, and that the act is genuinely a crime in terms of South African law.”

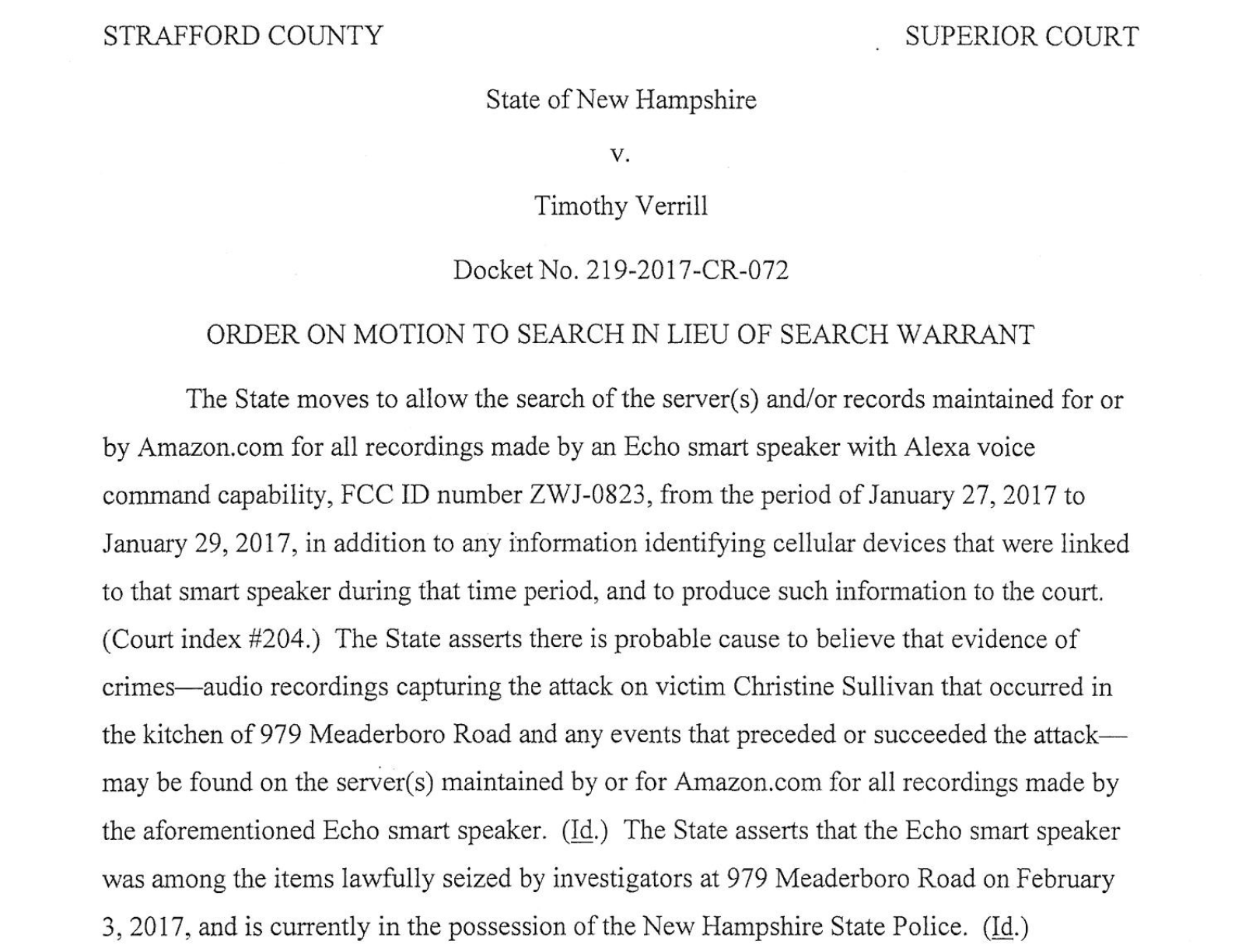

A US murder case from November 2018 demonstrates Fryer’s point. A judge ordered Amazon to release audio recorded by an Echo and stored on its servers. The court also ordered Amazon to hand over data about all devices that connected to the speaker. This extract of the court order (courtesy of TechCrunch shows the level of detail required.:

Amazon’s law enforcement assistance policy says it won’t disclose content without a search warrant or court order, and even then they will fight it in court if they think police are overreaching.

Google takes a similar stance: “If a request asks for too much information, we try to narrow it, and in some cases we object to producing any information at all,” its policy reads.

And that’s how it plays out in practice. Says Fryer: “They’ll review the application and say, ‘Yes, no, maybe.’ It can be a one-liner saying that your request doesn’t satisfy their requirements. They could say, ‘We’ll give you IP addresses but we won’t give you subscriber information.’ ”

Fryer says there’s another way for SAPS to get a bit of joy from tech giants. Most companies have online query forms for law enforcement agencies who need assistance. (See, for example, Google, Facebook and Amazon.) Police must send the request from an official government email address, says Fryer.

“They can request the preservation of an account.” (With account preservation, the company retains account information for a limited period to give police time to get a subpoena or court order.) But for anything substantial, says Fryer, they have to jump through the hoops.

It can lead to other information

But basic information leads to much more. In 2013, the Technology Analysis Branch of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada conducted some tests to demonstrate this. With readily available online tools (including Google) they could uncover intimate details without further court orders or special software. These new details could then be used to apply for further court orders.

Police can find detailed information based on a single piece of non-content data without needing further court permissions or special software. Compiled by: H Swart.

Police can find detailed information based on a single piece of non-content data without needing further court permissions or special software. Compiled by: H Swart.

Source: Technology Analysis Branch of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, May 2013.

The researchers concluded: “As information technologies become more common… and the more they become an extension of our very selves, the more sensitive and revealing subscriber identification information becomes.”

However, SA authorities seldom get what they want from tech giants. Companies like Amazon and Google release statistics on police requests for information biannually (although neither releases specific data on smart devices, or the crimes involved). Google reports date from July 2013 to December 2020. In all those years, SA made 28 applications. Only four were granted. The requests from SA to Amazon are so low that the company doesn’t report on them.

The alternative

Yet, there is another avenue for police: the device itself. It’s simpler, as this 2015 court ruling shows. A group accused of abalone poaching had their cellphones seized. Police used Section 20 of the Criminal Procedures Act; it allows them to search and seize evidence with a court order.

The suspects’ lawyer argued the order only applied to the phones’ physical hardware, and not the data. He argued that phones were actually “mini computers”, since they had software, could search the web, send emails, and store photos. (The jury is still out as to whether all smart devices are actually computers, but there seems to be a general consensus that IoT devices share some defining characteristics with computers. These include their abilities to connect to the internet, compute autonomously, and transfer data.)

But the judge sided with the prosecution, who argued that accessing a phone’s data after seizing it was akin to opening a seized safe to examine the contents. The judge thought it nonsensical that police could confiscate an electronic device, but be forbidden from accessing the data on its hard drive.

Fryer explains that if police wanted to seize a smart device, it would be exactly the same as searching your home for drugs, guns, laptops or phones: “The search warrant allows them to search any electronic media or anything that has the ability to store, transmit or transact with data.”

Yet, there’s a catch. What information is contained in IoT devices, which typically don’t have much memory? In 2019, Privacy International tried to find out what data was stored on an Amazon Echo. Despite their efforts, they remained unsure, concluding: “As connected devices... play an increasing role in criminal proceedings, we are concerned that... we do not know what data connected devices in the home may collect, including accidentally. We do not know what they store on the device.”

And one or two other ways

Still, there are other routes to private data. Often, a smart device is linked to an app on a smartphone. If you didn’t have a pin or other mechanism (like a fingerprint scan) to secure your phone, anyone could read your emails or access the smart device through the phone’s apps.

Daily Maverick asked Fryer whether police could seize a smartphone and access your accounts this way.

He said it’s possible, and explained there’s an ongoing debate in SA about whether authorities should require a two-step warrant to access data on electronic devices. Police would have to apply for a warrant to seize the device, and then apply again to access the data on it. The physical location of the device, and the data on the device, are treated as two separate places.

Says Fryer: “It prevents police from simply getting access to your phone and just flicking through every message.” Once police have someone’s phone, they’d have to apply for a separate warrant to access the accounts or any data or apps on the phone. “You’d have to create a relatively narrow investigative scope.”

But right now, there’s no two-step process. And, says Fryer, there’s other legislation through which police can access an electronic device, but they generally don’t use it. “The Electronic Communications and Transactions Act (ECTA) has a provision that can compel someone to give up their username and password. I don’t think it’s being properly applied.” In short, police aren’t taking full advantage of the law, says Fryer.

Although far cheaper than 1G phones, smart devices still aren’t entirely affordable. For instance, Deloitte’s Global Mobile Consumer Survey for 2019.

South Africans will have to wait for 5G networks to roll out sufficiently – and prices to drop – before IoT devices truly become mainstream. But, although the tech is new, old legislation already paves the way for the long arm of the law to get into these luxury personalised gadgets. How this ultimately impacts personal privacy remains to be seen. DM

Heidi Swart is a journalist who reports on surveillance and data privacy. This story was commissioned by the Media Policy and Democracy Project, an initiative of the University of Johannesburg’s Department of Journalism, Film and TV and Unisa’s Department of Communication Science.