Day 6, Thursday, 12 October 2023

Yesterday evening I went to visit some friends sheltering in various UNRWA schools in the neighbourhood. Entering the first of these was like going back in time nine years. Thousands have fled to the schools where, just last week, young children were sitting at their desks, learning.

Now every classroom houses 50-plus people, from several different families. In many cases, these 25m² classrooms have been partitioned into three or more smaller rooms by sheets of cloth, draped randomly across the room.

The families bring with them clothes, mattresses, blankets, pillows, kitchenware. But as more people flood into the schools, others take up places in the corners of the rooms, or in between the officially allocated spaces. Everyone needs a place in the end.

I know many of these displaced people personally, and I know that many of them have only just rebuilt their houses after previous bombardments. They haven’t really been able to enjoy their new houses yet, to make them comfortable and lived-in.

It took them between five and seven years to rebuild what was destroyed in 2014. Now the houses are gone once more and God knows when they will be able to rebuild them again.

Hisham, a friend of mine, asked me: “Why should I build a new home if the next war is only going to flatten it?”

I knew what I wanted to say: “To live in it.” But that answer would’ve seemed glib, so instead I replied: “First, let’s hope this war ends, that we all survive it, and that it’s the last of these wars.”

“It’s never the last time,” he said, angrily. After a while, he calmed down a little and said: “I know, one day, we will have a country.” He was referencing Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. Everyone wants a country. What he means is a state.

Atef Abu Saif was visiting Gaza with his 15-year-old son, Yasser, when Israel started its war on Gaza. (Photo: Supplied)

Atef Abu Saif was visiting Gaza with his 15-year-old son, Yasser, when Israel started its war on Gaza. (Photo: Supplied)

We sat for a while in a small room that my friend Ali had managed to create between two walls near the school gates. It felt like a gatekeeper’s cottage, but made from canvas. In this tiny space, he lives with four other members of his immediate family, as well as the family of his sister-in-law.

He was expecting his father- and mother-in-law to move in too in the next couple of hours. He had insisted I pop in and have a coffee with them. His wife prepared it on a small gas stove and we enjoyed our “displaced coffee” for a moment.

Afterwards, I walked round the school. Other friends invited me into their canvas “rooms”. Despite the situation, people are still generous and welcoming. Everyone offered me coffee or tea and even biscuits they’d brought with them. In these “coffee sessions”, you hear horror stories, tales of miraculous survivals and difficult journeys to this new shelter.

We then moved from one school (boys) to the neighbouring one (girls) through a small door in the wall that separates the two. Ramzi, an old friend, told me his son was administrating the shelter. “He’s the boss here,” he said. He then suggested we pay our condolences to a man there who had just buried four of his kids. The blood of his children was still on his clothes and tears ran down his cheeks continually as he spoke. At one point, he looked to the sky and said helplessly: “It is His wish.”

Ramzi told me that some people coming into the schools witnessed the loss of loved ones while on the road, and had since taken the risk of going back to retrieve their bodies for burial. “Every hour, there’s a new funeral,” he said. Many go to check on their houses and search for lost relatives. Some come back, some get killed in the process. Few come back with the people they were looking for.

A journalist, who was reported to be dead and buried under the rubble with her children, was found alive the next day when her dad decided he wanted to hear her voice on her answerphone message. He rang her and, to his complete surprise, heard her voice: unrecorded, live, alive. She and the kids were waiting to be rescued.

In the fourth school we visited, I met with my close friend Bassam, Hisham’s older brother. Bassam has spent many years in Israeli jails and knows hardship all too well. His “room” was on the third floor of the school, and when I asked him why he didn’t choose one on the ground floor, he said he was lucky to get the one he did. He and the other men had just spent the day preparing the school, cleaning it and getting it ready to be a new town.

When night fell, I decided we should stay in the Press House, as the hotel was no longer safe. The Press House had electricity at least, if not internet. There were five of us planning to stop the night there, it seemed: my son Yasser, my brother Mohammed, the journalist Hatim, Abdullah (a lawyer and activist) and me. We prepared dinner together: eggs, beans, cooked tomato. After that, we sat around the narghile, as explosions sounded in the distance and the Press House shook from side to side. Being Palestinians, we enjoyed the opportunity to analyse the situation, politically.

Being Gazans, we also knew which strikes were coming from the warships in the harbour. On the radio news, the presenter was talking about the departures of what he called 15 “moons”, meaning souls. Such language doesn’t help to lessen the weight of what we were hearing about.

Suddenly a piece of shrapnel fell into the front garden of the House. It made a terrifying sound. We ran to check it hadn’t hurt anyone and calculated that the original missile it was part of must have struck the shop next door, crashed through the roof of the building, then flown off into our front garden, via the door of the shop.

We picked it up and carried it into the hall. It was hot to touch and heavy, and we set it down next to the jackets of the three killed journalists. The whole scene told a story of the growing devastation.

Mosquitoes attacked and bit me as the evening went on. Abdullah told me how his sister was allergic to them, as well as to dust. We finished the remains of our supper. By now, the war has somehow become normal. At the start, you count the strikes and try to work out where every single one was, but after a few days you stop counting. I think some kind of auto-pilot has kicked in, a survival mode developed in the 2014 war that allows you to stop paying too much attention to every detail.

For a few hours, we managed to disconnect from the world. Not having internet helped. Now that the electricity has been cut off, we are entirely dependent on the solar panels. This means we have to watch our consumption. Water has been cut off as well, but we have enough for a day stored in the tanks.

This morning, I walk with Mohammed towards the harbour. Two nights ago, many buildings in Institution Street were destroyed, making us too nervous to walk anywhere near the beach. So we turn inland and head east up Omar Mokhtar Street towards al-Shifa Hospital. The Karmel Tower seems to be collapsing. Concrete and debris are scattered across the street. Delice Coffee, one of Gaza’s main coffee shops, has been damaged.

On my way back to the Press House on al-Shuhada Street, I see a flag still waving from the third floor of an attacked building.The building is resisting the fate of so many other buildings and somehow still stands. The Abbas Mosque has collapsed, but its dome is left completely intact. Now the dome stands, pristine, if leaning at a slight angle, on top of a pile of grey rubble.

I arrive at my flat in the Saftawi neighbourhood of Jabalia. As my family and I now live in Ramallah, we don’t use the flat often and we don’t use the water. So now there’s plenty of it. I fill the bath with hot water and take a long soak. I wash my clothes in a pan, scrub them and leave them hanging out around the apartment.

Knowing there’s a chance the flat will be destroyed in this war, I go round collecting all the photos from the walls, putting them to one side. I look to the shelves for something to read in my spare time, of which I will have plenty. I pick Anna Karenina and also grab two copies of my book, The Book of Gaza, vowing, if I made it back to the hotel after the war, I would leave them in the reception on its guests’ bookshelf.

Atef Abu Saif has lived in UN shelters in schools and has been displaced multiple times during Israel’s war on Gaza. His book tells of the struggle to find food and maintain contact with the outside world, as well as his decision to leave his father in the north for his own son’s safety. (Photo: Supplied)

Atef Abu Saif has lived in UN shelters in schools and has been displaced multiple times during Israel’s war on Gaza. His book tells of the struggle to find food and maintain contact with the outside world, as well as his decision to leave his father in the north for his own son’s safety. (Photo: Supplied)

Day 7, Friday, 13 October

A house on our street was destroyed last night. Fourteen people were reported to have been killed, initially, but by the morning it would be 27.

Our street is named after the refugees from both Jaffa and Howj (a village northeast of Gaza), so sometimes it is called the Jaffan Street and sometimes Howji Street. In recent years, the Howji name has grown more widely used. I know many of those who were killed. They are my neighbours.

All around the street, buildings were hit. Now the only thing that seems intact is a single banner strung across the middle of the street, welcoming Ramadan.

When the attack happened, I was at the Press House. I called Ibrahim to ask about my dad and the rest of the family. One of my half-sisters, Amina, lives in a flat opposite the targeted building. Luckily, she had moved to my father’s house earlier that day.

Samah, my other half-sister, who lives near the beach, way up north, near Beit Lahia, has also moved into my father’s house. After the attack on Howji Street, she made the decision to move again, to a school shelter in Nasser or Shatti Camp. She gave birth to her third child just a few days ago.

In the same attack, my friend Mohammed Mokaiad’s wife was hit by a piece of shrapnel that came through the roof of their house and caught her in the neck. Her injury is critical. I tried to contact him to ask if he needed anything, but I couldn’t get through. The Press House’s internet was down yesterday as the main router had no electricity.

In the House, we’ve instigated a new policy of austerity in our usage of electricity. We only use one lamp at a time. Also, there’s no hot water today: the normal tank is empty, only the tank that supplies the boiler has any water in it.

During the night, Yasser and I slept in the open air, near the garden at the front. Most of those sleeping in and around the House wake up at 5am. I hear them talking about how the Israelis have ordered the people of Gaza City and the north of the Strip to move to the south.

“That’s a rumour,” I say, dismissively, as I sit up. “No,” someone replies. “It’s true. My friend just told me over the phone.” There’s no internet to confirm or deny it, so I lie back down and try to sleep some more. At 7am, after two hours, Mohammed wakes me up saying we have to evacuate the place. “Why?” I ask. Out front, on the street, the Red Cross employees were evacuating their building. “All the international organisations are heading south,” Mohammed says.

There are 10 of us still here. We go to the entrance and watch the cars of the Red Cross employees pulling away. Everyone seems frightened; even the little cat sitting under the table outside the closed pastry shop looks terrified. We agreed that, come the afternoon, we will decide whether to leave and head south or stay.

Yasser, Mohammed and I drive back to my flat in Saftawi. I pack up all the family photos and souvenirs. I ask Mohammed to put three mattresses in the car and three pillows as well, in case we needed to move quick. I place various essentials onto a kufiya, which I then wrap up into a bundle. Was this what the Nakba was like, I wonder.

As we prepare to leave, a missile hits the house owned by the Abu Lihia family not far away. Later we will learn 15 people were killed by this strike. Such things become normal. With every strike, though, memories scatter along with the debris, rubble and shrapnel; histories are being erased. And with every blare of an ambulance siren, someone’s hope dies.

The streets are full of people. They walk without particularly knowing where to go. Like us on the night we fled the hotel, they just want to keep moving. Many are weighed down by bags, while simultaneously dragging their crying children behind them. Who can give them what they’re looking for? Safety. Survival.

Kamal, a friend from my university days, phones and proposes we come to stay at his place in Nuseirat. Back at the Press House, I ask Hatim: “Where are we going to stay?” Our decision was to drive south and see if that’s what everyone is really doing. “In the worst case scenario,” I say, “if we’re unable to return, we can sleep in the car.”

“Good idea,” Abdullah says. Hatim suggests that in such a situation we could always go and see Hikmat, the editor of Sawa, the news agency. It would be good to see how things were on the ground down there.

When Yasser hears that we’re heading south, he asks: “South to where?” “Believe me,” I say, “I don’t have answers to every question. Half answers have to suffice sometimes.” Yasser, who sometimes seems to be the most anxious of my children, who is afraid to go to the supermarket at night on his own, now seems much stronger and braver. I ask him: “Are you afraid?” He replies: “Of what?” This is good enough for me.

The businessman Abu Sad Wadia is going round the neighbourhood distributing items from his store – yoghurt and milk – for free. He sends some bottles to the Press House. I drink mine – peach flavoured – wondering when I’ll taste something as sweet again. DM

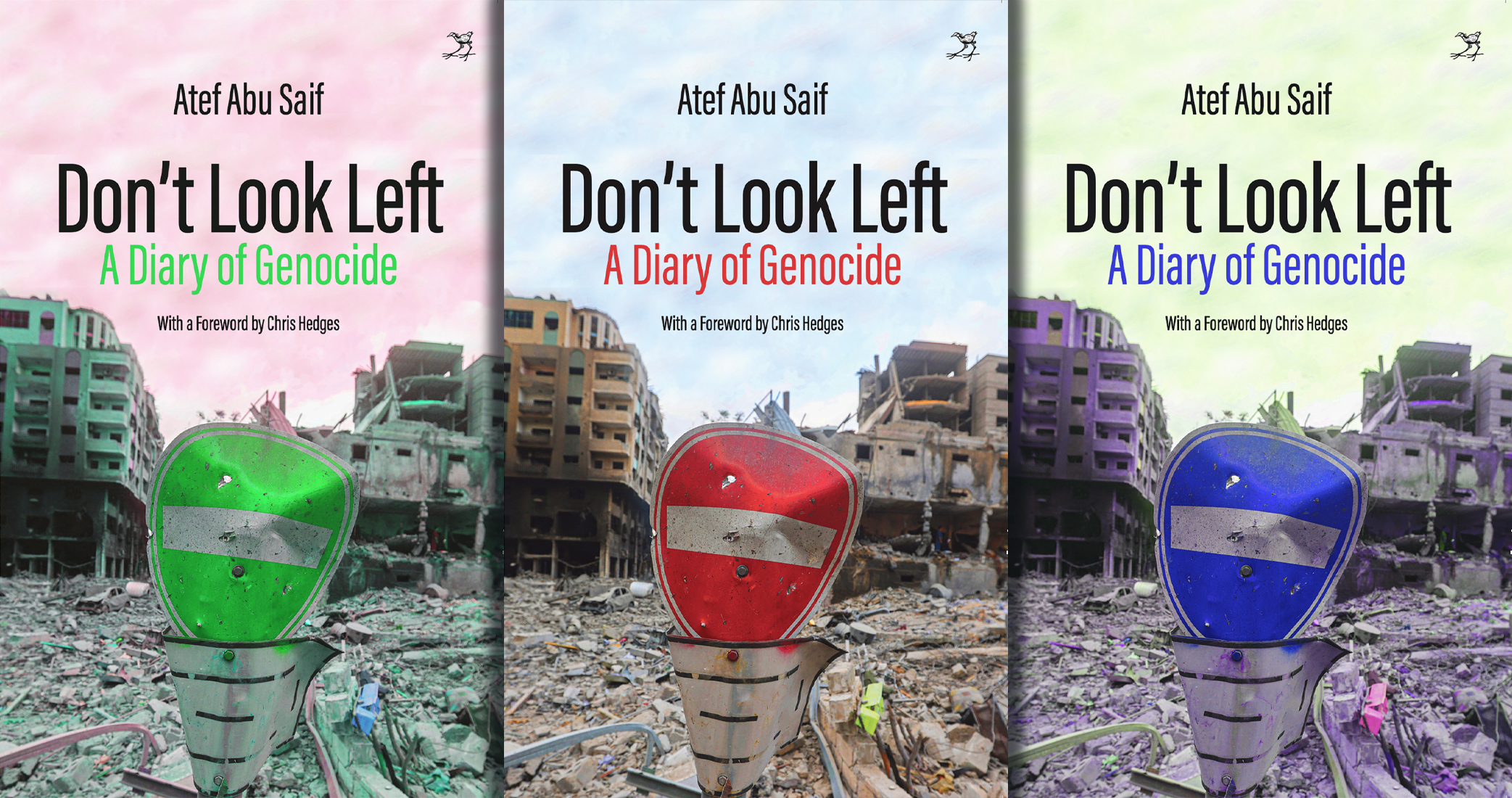

Don’t Look Left: A Diary of Genocide is printed in SA by Jacana Media and costs R300.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R35.

You may write a letter to the DM168 editor at heather@dailymaverick.co.za sh

Atef Abu Saif lived in UN shelters in schools and has been displaced multiple times during Israel’s war on Gaza. His book tells of the struggle to find food and maintain contact with the outside world, as well as his decision to leave his father in the north for his own son’s safety.

(Photo: Supplied)

Atef Abu Saif lived in UN shelters in schools and has been displaced multiple times during Israel’s war on Gaza. His book tells of the struggle to find food and maintain contact with the outside world, as well as his decision to leave his father in the north for his own son’s safety.

(Photo: Supplied)