Without any conscious intent, I have found that sometimes, when trying to bring a character to life, an instinct in me would force me to withdraw from the world of the set. Generally speaking, a movie set is a wonderful place for an actor to be. Everyone is excited to be working on a new project that will help pay the bills, and old friendships are rekindled. Yet at times I felt the need to distance myself.

I’m often described as “the crazy actor who camps in the bush”, but becoming an outsider has been a deliberate decision on my part. I’ve always wanted to remain something of a stranger on set and to the other actors, since this has enabled me to choose how to interact and joust with the movie set – actors and crew – as an entity that I am part of, but, at the same time, apart from.

For example, throughout the six years it took to shoot all 36 episodes of the hugely popular Afrikaans television series Arende, I was inadvertently exploring my relationship as an actor with movie sets and the notion of maintaining a level of apartness.

It took many hours in many bars with different kinds of strangers, and hiking up many nearby mountains, to maintain a modicum of remoteness from the world of the screen.

I must thank all those garlic farmers, travelling salesmen and ad hoc boozers in the Hangklip Hotel, Froggy’s Barrydale Hotel, the Royal Hotel in Douglas and the Pofadder Hotel for their company. Their stories about the realities of their worlds kept me from being completely absorbed by the mini-world created by the actors and the crew on the set of Arende, which helped me to maintain the integrity of the character of Sloet Steenkamp.

From a young age, long before I became an actor, I always felt different. Over the festive season, for instance, when everybody is supposed to be in a party mood, I always feel a little depressed, a little distant. I remember an incident from my childhood when my parents took me to go and play at the house of a friend in Fort Beaufort. After a while, I found that I liked neither him nor his other friends and the games they played, so I soon disappeared.

When they realised I was gone, they searched high and low and eventually found me sitting inside a cupboard, enjoying the silence and the smell of the exotic wood. They shook their heads because to them I was something of a freak. In retrospect, I agree.

Over the years I’ve realised that there are times when I don’t fit in with the people around me, which has had the effect of making me feel even more inadequate at trying to be a “good guy”. I’ve always known that I am an outsider, and I believe every actor has to arrive at that magical island where it’s okay to be different and set up shop on the beach. Google can teach you many different things, but certain acting tricks can only be learnt through experience.

While working on the TV series Heroes in 1984, renowned director Manie van Rensburg was unhappy with the performance of one of the actors. In movie parlance, to “feed” another actor is to give them the lines you speak in the scene so that they can react in close-up, but you are not on camera. To “feed” this particular actor, Manie placed me so close to the camera that my ear was touching the lens.

“I need you to help me out here, Ou Grote. Just blow him out of the water,” he said softly in my ear and winked conspiratorially.

Having watched the flat performance of this actor during all the previous takes, I knew exactly what Manie meant. So I overacted as grossly as I could. The other actor was so surprised he was shocked into an acceptable, cuttable performance.

Fifteen years later, acting in a big international movie in Zululand, I had to call on that trick again to aid the performance of the leading lady, a famous American actress and smouldering blonde beauty. She was such a big name that the entire movie budget emanated from her status. She was the queen of the set, and you got the feeling that if she didn’t like you, you would be on the next bus back home.

But then one day, when we were shooting a pivotal scene, the so-called money scene, she struggled to get it into the can. The director was a wonderful man, but he did not know how to work with actors. The scene involved me and the young actor Nick Boraine: we played the roles of two men who had to bring the leading lady the terrible news that her husband had been gored to death by a buffalo.

In the scene, Nick and I had to come around the corner of a stoep where we would run into the leading lady. On the first take (to us South Africans, an extremely expensive one, with three cameras rolling 35mm film), our leading lady just stared back at us blankly after we had told her the news of her husband’s demise.

Initially, I thought perhaps we South African actors were too weak for her, that our acting wasn’t up to standard. She had acted opposite several Hollywood stars and maybe they knew how to do stuff that we had never learnt.

However, after the second take, when she again did nothing more than stare at us blankly, I knew the problem lay with her and not us. The director was standing behind us, shaded from the blistering Zululand sun by a thorn tree. When he called “cut”, I looked around to see an expression of helpless defeat on his face.

Nick and I returned to our first positions around the corner of the building, waiting for the third take. I recalled Manie’s advice to me on the set of Heroes and said to Nick, “You know what we’ve got to do now?”

“No, what? The woman’s nowhere, she’s dead in the water!”

“That’s exactly it, Nick. So we’ve got to blow her out of the water.”

“And how the hell are we going to do that?”

“Simply do the worst, over-the-top, bullshit acting you’ve ever done,” I said.

“Like what?”

I could see that Nick, who was a sensitive young man and by nature averse to grossness, was struggling to get his head around my suggestion.

“Like gross commedia dell’arte, broad and terrible acting.”

“No way, man, I can’t do that!” he said, wide-eyed. “What about my performance?”

“That was already in the can after the first take, boet.”

“ACTI-O-O-O-N!” was called and we set off again for our meeting with the leading lady.

She walked up the stoep and stopped when she saw us. The Panavision camera on the long tracks stopped. Everything stopped. And then Nick shouted very loudly: “Your husband’s fuckin’ D-E-E-A-A-D! He was gored by a fucking buffalo bull!”

A look of true shock spread over her face. Her mouth was moving almost imperceptibly but with no sound coming out.

I then spoke my own line as gently as I could. “It all happened very suddenly and quickly. He did not suffer at all.”

And then the leading lady burst into tears. Everyone was deeply moved. Behind me I heard a breathy, “Yes, yes, yes!” It was the director jumping up and down.

Some months later, I was sailing to Japan on a Safmarine container ship that, for a price, took passengers on board. At Port Klang in Malaysia, I left the ship to go into the town. On the quayside, a scrawny man was squatting beside a pile of DVDs that were for sale. And there, way before the film’s release in Hollywood, was a rough copy of the movie.

I bought it and played it when I got back to the ship, fast-forwarding to that scene. There it was, a little hazy at the edges and with poor sound, but still the real deal. It would blow you clean out of the water. DM

This article is more than a year old

South Africa

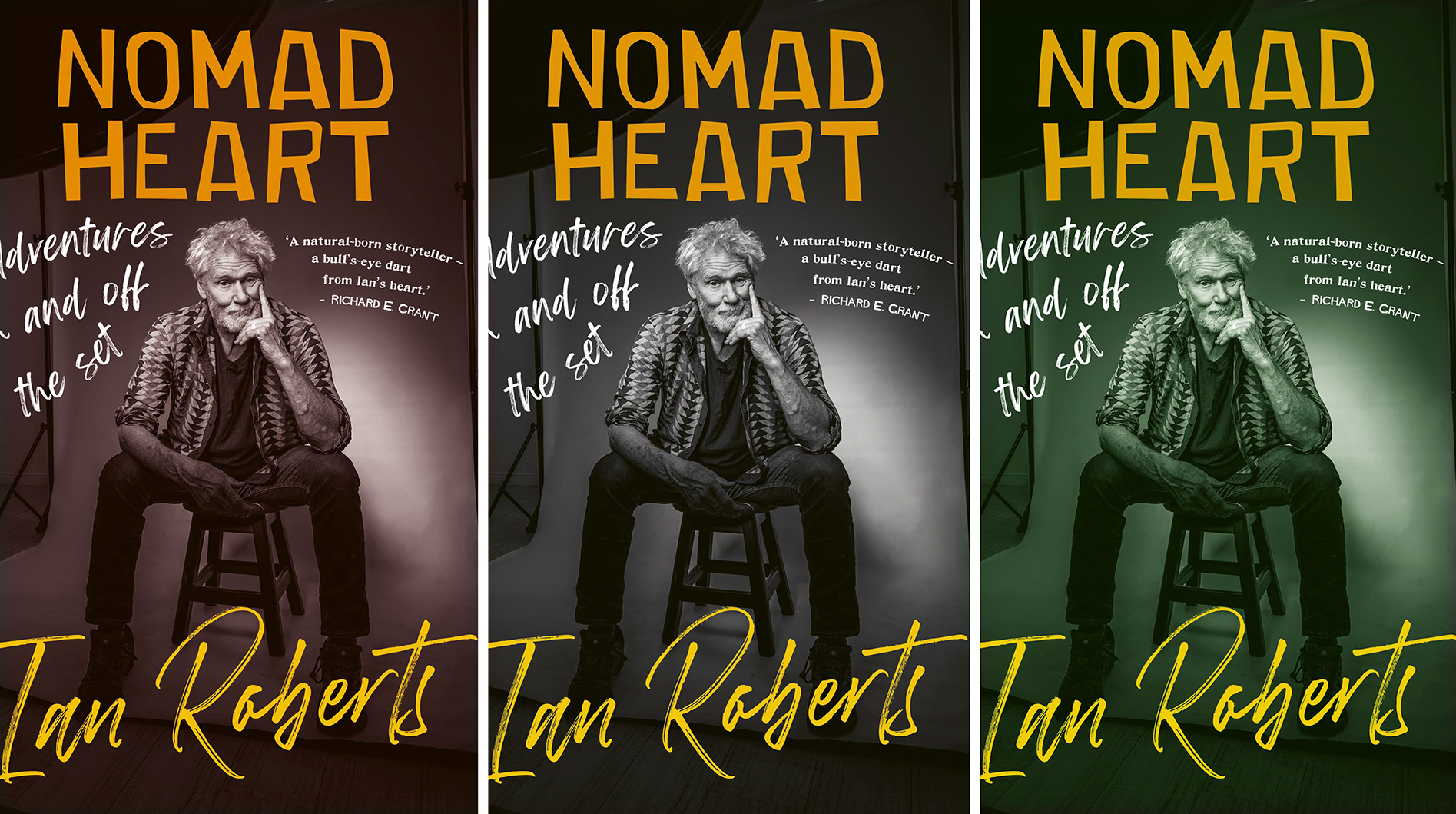

A pint of the best, Boet, as Ian Roberts tells (not quite) all in Nomad Heart

Ian Roberts is something of a South African icon, renowned for his roles as Boet in the classic Castrol advertisements, Captain Smit in the Oscar winner Tsotsi and as Boer rebel Sloet Steenkamp in Arende. His autobiography, Nomad Heart, is published by Jonathan Ball.