Mina: Day three of Hajj.

We are at the foot of the winding path, looking up the hill to the second floor of the jamarat, the stone walls that represent the devil who had tempted the prophet Abraham against the sacrifice of his son. There, the Saudi soldier greets pilgrims. I look up in surprise. It’s not that the soldiers and police officers marshalling the crowd through these last days have been discourteous. Not at all. Most have been polite. And when I’ve seen some lose their composure, I’ve admired their restraint. Yet even among the experience of the general cordiality of the security personnel, there’s a note of respect so sincere in the greeting of that soldier that morning, that my bowed head whips up in gratitude.

“Ta qaballahu minkum”. May Allah accept it from you.

I feel the tickle of tears. We are at the height of our Hajj journey now and I’m wearing a weariness deep into my bones. My white clothes are stained by two days of exertion and the spilt blue ink of a fountain pen. My right ankle, ostensibly sprained three weeks prior, is pounding in my shoe.

It’s not been long since sunrise but the day’s already grown too hot. Far too hot. I will my tired body up the path, breathing deeply, my mouth dry and my spirit clenched tight. I’m not so tired as I am grateful. Not as grateful as I am anxious. Not so anxious as I am conscious of self, and others. I felt, I realise now, a year later, deeply fulfilled.

A long exposure photo shows pilgrims attending the symbolic stoning of the devil ritual at the Jamarat Bridge during the Hajj pilgrimage near Mecca, Saudi Arabia, 16 June 2024. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Stringer)

A long exposure photo shows pilgrims attending the symbolic stoning of the devil ritual at the Jamarat Bridge during the Hajj pilgrimage near Mecca, Saudi Arabia, 16 June 2024. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Stringer)

There are five days of Hajj. And for the two-and-a-half days until that moment, I had been immersed among fellow travellers, fellow pilgrims. I was ensconced in a cocoon of sameness, in a place where we were all alike, all equal. All of us in a state of ihram, men wearing two pieces of unstitched white cloth. The women, in colours of their choosing. But all of us, stripped down to our most basic essence of humanity, without the disguise of perfume, cosmetics, or soap. And at peace with the world, forbidden to even swat a fly.

So the soldier, in his fatigues, was an outsider. And in that greeting, physically close, but so far outside that experience, was an acknowledgement of the struggle, the pain, but also a respect for why we were there – the quest for a divine acceptance.

Johannesburg – Before travelling

Hajj is the fifth pillar of Islam, incumbent on all Muslims anywhere in the world, at least once in their lifetime, if they have the health and resources to make such a journey. The striving to perform Hajj is one of life’s certainties for us, the transformative journey, returning you home as a new person.

As a South African, my Hajj journey began in 2014. I was working in my bedroom one night when my sister called out for my identity number. She was adding our names to the list of South African applicants for Hajj. I sent her my details and forgot about it altogether.

Managed by the South African Hajj and Umrah Council (Sahuc), a non-governmental organisation that acts as the national regulator for the administration of South African Muslim pilgrims, the list is long and not without controversy – especially when the process is not often understood.

We would pause once a year to check how far up the list our names had trekked and in 2019, we knew our turn would soon come. In January 2020, we received our accreditation. We were to be a big group – my sister, my brother and his wife, my three aunts, and four cousins. And then the world came apart with the Covid pandemic. The Hajj was cancelled that year. And strict restrictions on numbers were enforced for the following two years. But our turn would eventually come.

In January of 2023, Sahuc released the first list of South Africans accredited to perform the Hajj this year. All our names were on it, even, poignantly, my aunt who had passed on just a few weeks earlier.

We were among the initial 2,500 South Africans accredited. This number was later increased to 3,500 after Saudi Arabian authorities increased the quota of South Africans eligible to perform Hajj in 2023.

It took some months for the quota to be filled; the weakness of the South African rand, inflation and a stagnant economy had raised the costs of Hajj travel prices significantly. But it’s not a uniquely South African problem. Around the world, the travel costs associated with Hajj continue to be high. It was also the first Hajj with a full quotient of pilgrims after the pandemic. It would turn out to be the largest Hajj on record.

Meanwhile, the news of our accreditation is greeted with an outpouring of love I had not anticipated. From the farthest reaches of my acquaintances to my closest relatives and friends, I am surrounded by gifts, wishes, quiet entreaties and vociferous admonishments.

Pilgrims attend the symbolic stoning of the devil ritual at the Jamarat Bridge during the Hajj pilgrimage near Mecca, Saudi Arabia, 16 June 2024. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Stringer)

Pilgrims attend the symbolic stoning of the devil ritual at the Jamarat Bridge during the Hajj pilgrimage near Mecca, Saudi Arabia, 16 June 2024. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Stringer)

In little strips of paper and WhatsApp text messages, friends and family note down their prayers, requesting that I repeat them on their behalf. My bags are filled with snacks. I feel dizzy trying to keep up with all the advice I receive.

The start of this journey begins with an accounting of interpersonal relationships; an attempt to restore harmony within yourself, seeking forgiveness from those around you, before repairing your relationship with the Divine.

Madina: Three weeks before the start of Hajj

In the rows of people sitting in the Masjid al Nabawi, the mosque of Prophet Mohamed and the site of his grave, we wait for the call to prayer. The mosque is full.

None of us has a passport – upon landing in Saudi Arabia, our passports are handed over to the Saudi government, only to be returned shortly before we leave. It’s not exactly clear why. So it’s a curious experience of identity.

We have been here for hours already – the only way you can secure a comfortable place inside is to arrive early. And expect to stay put for hours.

As we wait, some of us read from the Quran; a group of South African women near me talk in hushed tones, their accents unmistakable in a glorious medley of language and movement. To my right, a group of women I thought were Turkish, seated among a group of Turkish women, turned out to be from Dagestan, Russia.

We needed two Google products, Translate and Maps, to exchange this information. I’m embarrassed when the only thing about Dagestan I could ask after was the MMA fighter Khabib Nurmagedev. The only person they could remotely associate with South Africa was the Zimbabwean speaker and social media star, Mufti Menk.

We laugh at the smallness of our worlds and exchange sweets.

To my left, a group of women from Burkina Faso have formed a small circle. Like many others, they are dressed in a uniform that identifies them with others from their country. They are wearing orange and green wax print dresses with lanyards identifying themselves and detailing their places of stay.

As the woman nearest to me extends her hand in greeting, we talk about who we are and the work we do. She is a doctor, worried about the future of her country. We exchange contact details and promise to be in touch. But as the crackle of the speakers around us signals the start of the call to prayer, she holds my hand tightly. Pray for peace, she asks, “Pray for peace, my sister. Pray for peace for us.”

We come on Hajj, each of us on our own journey, expecting renewal, all of us hoping that the faults of the worlds we have come from may be repaired.

Makkah: One week before Hajj

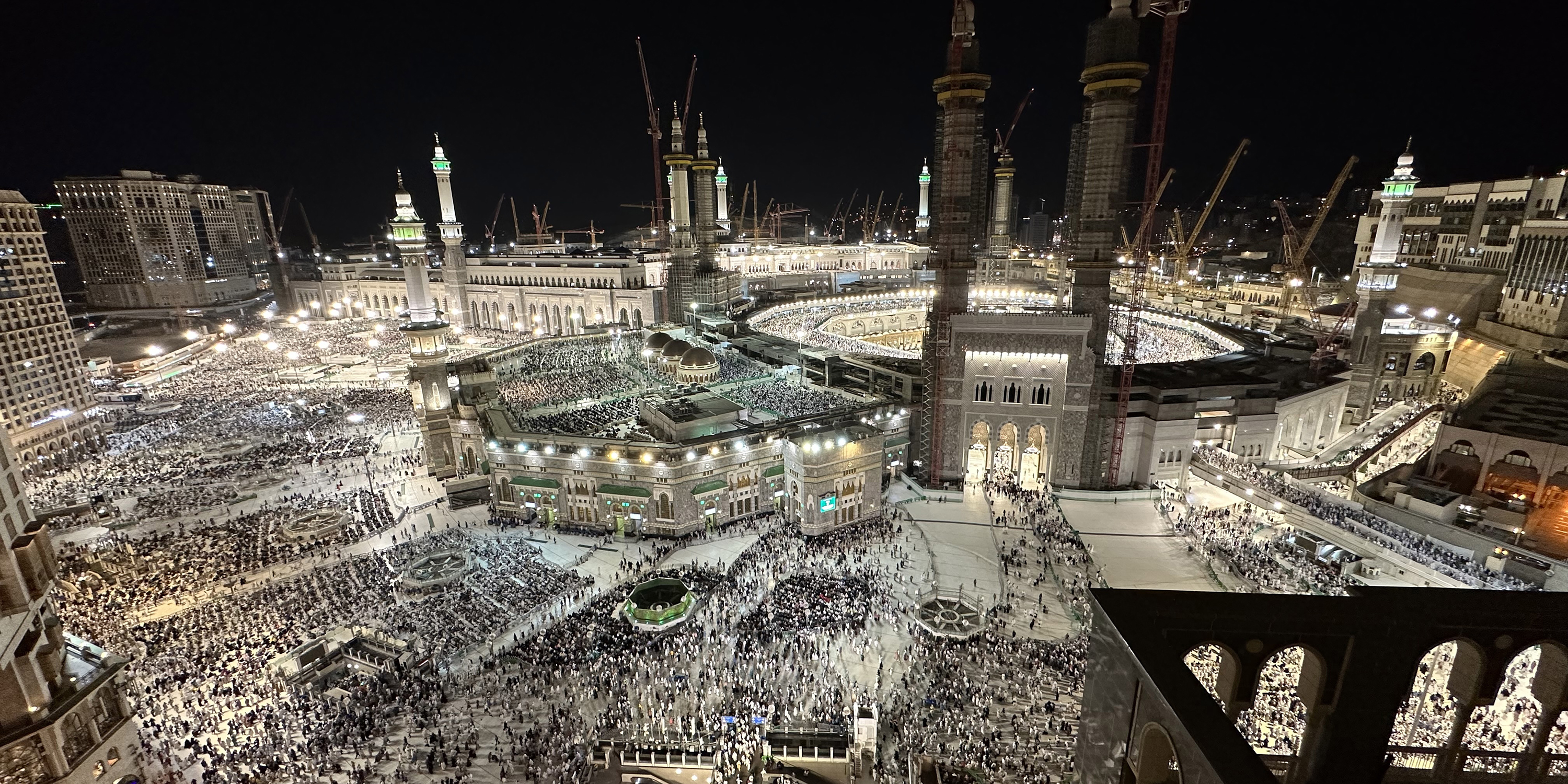

The streets of Makkah are heaving.

Daytime temperatures are over 40°C. The interiors of the Grand Mosque, the Haram, are hardly accessible. There are people everywhere. And they are from everywhere. Japan. Indonesia. Bosnia and Herzegovina. Chad. China. Everywhere you look, people are walking. It is wondrous. In incredible concert, like waves licking the shore and then retreating, people move to and from Haram.

In that crowd, you begin to understand something of your smallness within the universe and something of ceding the idea of control – you begin to ignore the little bumps and shoves; you move along, find the composure to remain calm when surrounded by difference, and understand what it means to belong to something greater than yourself.

Aziziyah: Four days before the start of Hajj

The closer to the beginning of the five days of Hajj we were, the more expensive hotels in central Makkah became. So at some point during the 10 days before the commencement of Hajj, the majority of South Africans moved to Aziziyah, east of Makkah and adjacent to Mina. Here, in humble hotels and apartment blocks, we ready ourselves for Hajj.

Ours is among the smaller of the South African groups. We gather in the prayer hall of the hotel to begin our introduction to Hajj.

“These are the days we have been waiting for,” says Moulana Bham, the spiritual guide of our group.

Mina: The first day of Hajj

On the first day of Hajj, we prepare ourselves in the early hours of the morning. Scrubbing the world off ourselves, we enter into the state of ihram, and await our buses to Mina.

It’s a short journey and there’s an impressive system of rotating the same buses between all the South African groups. While the rest of our group files into two other buses, about 10 of us file into the last bus to Mina.

The roads are shockingly empty; the bus system really does work.

Known as the tent city, Mina – nestled between mountains – is about 10km east of Makkah. Here, pilgrims congregate on the first day of Hajj. South Africans have been placed in Camp D, in a section apportioned for African pilgrims. When our bus reaches the tent, we haul our too-heavy backpacks and right ourselves for what lies ahead.

Pilgrims gather on Mount Arafat during the Hajj 2024 pilgrimage, southeast of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, on 15 June 2024. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Stringer)

Pilgrims gather on Mount Arafat during the Hajj 2024 pilgrimage, southeast of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, on 15 June 2024. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Stringer)

The wristbands we’ve been given to identify us as South African pilgrims are checked at the entrance of the camp and we follow the path to the tent in which we’ll be based. Peeking into the tent from the pathway, I’m stunned. We’ve been told to expect cramped conditions with sparse amenities. Camp D is distinct from Camp A, which hosted about 50 South Africans last year, where you have more space and better amenities, at a greater cost.

So this is Hajj. The full experience. The sight of people seated tightly next to each other, with hardly any daylight between them, is jarring. And any progress I may have made reconciling an idea of selfhood to being among many others, wavers.

Standing there, backpack in hand, trying to reconcile the space with the objective of Hajj, we’re told there’s no room in the tent for us. With men in an adjacent tent, the men of our last bus are already seated inside. Sahuc, the Hajj regulator, had said in various messages that each of us had been accorded a space – they had counted, and any lack of space could only be attributed to the wrongful hosting of pilgrims who’ve been accredited through other channels and should be in other camps.

We’re ushered inside, sharing seats, while a simple breakfast of croissants and fruit is passed around. I type a message to a Sahuc official I know. He’s not there, but he assures me everything will be worked out.

There is a nervous energy inside the tent.

Outside, our travel agent is in heated discussions with Sahuc, and after a couple of hours, another tent is set up, allowing several pilgrims to pass through, and we have space. Walking gently between the women in our tent, apologising profusely, trying not to tramp on someone’s toes, or meet someone else’s resting eyes, we get to our little spots.

Here, I fish out my journal and pen from my backpack and work on the list of prayers I wish to say the next day in Arafat. It’s terribly hot. The air conditioning system is blowing out hot air.

“It’s harder than climbing Kilimanjaro,” a pair of women who had climbed the mountain a few months prior assures us. “It’s almost as hard as the Comrades,” a marathon runner agrees.

Meanwhile, much of the talk around the tent is about the state of the toilets. It is deliberated upon with a gravity usually reserved for the state of global politics. With just 32 toilets allocated to the South African pilgrims, and no maintenance of the lavatories during the day, much of the difficulty you are told to expect during Hajj is here – the toilets of Mina.

The queues are interminably long. And the facilities are, well, filthy. And when there is a disruption to the water supply for two hours that morning, it grows worse. Some refuse to eat or drink to avoid the toilets, but end up in the medics’ tent, severely dehydrated.

The water gets restored, and as the day passes, there’s news of an empty camp allocated to Iranian pilgrims across the road from us – so we rush to use their toilets. Later, when the Iranian camp is locked, we are told the toilets allocated to Nigerian pilgrims are in much better condition, so off we go there. But even the toilets eventually become bearable once you know your way around the worst of them.

Seated next to each other in that tent, hot, nervous and uncomfortable, we soon began to laugh. Among our group were at least two doctors. Someone else was an executive at a petrochemical company, another person was a lawyer at a hospital in Australia. So many women in that tent had accomplishments and importance that ought to outstrip this measly space. And yet there was nothing we could do about any of it: the weather, Sahuc, the air conditioning, the toilets, the lack of space. Absolutely nothing we could do about it. And by that night, the space that seemed so confined appeared to expand; to accommodate the bond that would grow among these women.

We prayed, exchanged confidences, shared our snacks, laughed, shared our highest hopes, and went to sleep beside each other – if not happy, then certainly content knowing that even the most difficult moments become easier when you accept the limits of yourself – and consequence.

Arafat: The second day of Hajj

When we reach the plains of Arafat – the patch of desert that hosts the most significant time of Hajj – we are met with a host of mosquitos and a malfunctioning fan in a large tent.

We’re reminded that in a state of ihram, we cannot harm any creature and so cannot kill the mosquitos. Instead, we have to sit with the irritation, sharing water sprays to alleviate the itch.

This is the most sacred day we are to ever experience; we are granted an audience with God. Encouraged to pour our hearts out, “Allah understands English,” Moulana Bham had said previously.

Here, our Hajj, we know, will be defined. So mosquitoes are not meant to distract us. We eat ice creams for breakfast and wait for the appointed time of the wuqoof – the period of the afternoon where we stand before God, alone with what we’ve done, what we want to do, the people we’ve been, the people we want to be.

Muzdalifa: The second day of Hajj

Reaching Muzdalifa, we are exhausted. Here, we must rest under the stars – rendered invisible by the city lights. Unfurling a sleeping mat onto an embankment our group had reserved for us, I’m a little dazed. It’s been a whirl of emotion and activity. And still, it felt like it was not enough.

There was more to say in Arafat. I had also been trying to be more conscious of myself; my own instinct to be annoyed at something, or put out, or angry. It is a consequence of this journey, I think, that you are made to locate yourself physically; to reconcile a physical body, and its weaknesses within the space I find myself; how I relate physically to the person beside me, as we are all going towards the same thing.

What it has all amounted to, is an exercise in Muzdalifa. Here in Muzdalifa, among throngs of people, we bend down to collect pebbles from the sand, filling little bags with which to symbolically stone the devil, an act that invites us to think of repelling whatever it is that prevents us from the act of submission to the decree of God.

Makkah: The fourth day of Hajj

There is no point hoping for the Haram to be less crowded – it is crowded. The only way to survive the crowd is to merge with it.

As I perform the sa’aee – moving between the mountains of Safaa and Marwa – I think of the woman whose actions we repeat here. Hajer, wife of the prophet Abraham, stranded in the desert without food or water, anxious to feed her son Ismail, ran seven times between the mountains of Safaa and Marwa, searching for water.

It was an act so beloved to God, that hundreds of years later, we walk between Safaa and Marwa, just as she did. The act of a woman, of a mother seeking to feed her child so cherished in memory, we walk that walk, men, women, children.

And I learn, again, that being a good Muslim is being a good person; to do good for good’s sake. To give for giving’s sake.

Jeddah: Three days after Hajj

Hajj is a deeply individual journey. But the greatest lesson it affords is locating yourself within a multitude of meanings.

There is much to learn from negotiating the boundary between self and others; between exercising your rights, the force of your ambition, religious or otherwise, in the morass of humanity, all walking the same path.

Two million people travelled the same path in 2023, coveting the acceptance of their prayer and their pilgrimage, searching for a new beginning. Amid that effort, we found something else too – camaraderie, compassion, and a unique experience of love as the foundation for change. DM

Khadija Patel pushes words on street corners. She is passionate about the protection and enhancement of global media as a public good and is the head of programmes at the International Fund for Public Interest Media. She is the former editor-in-chief of the Mail & Guardian in South Africa, a co-founder of the youth-driven, award-winning digital news startup The Daily Vox and a vice-chairperson of the Vienna-based International Press Institute. As a journalist, she has produced work for Sky News, Al Jazeera, The Guardian, Quartz, City Press and Daily Maverick, among others. She is also a research associate at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research.

Muslim pilgrims gather on Mount Arafat during the Hajj 2024 pilgrimage, southeast of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, 15 June 2024. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Stringer)

Muslim pilgrims gather on Mount Arafat during the Hajj 2024 pilgrimage, southeast of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, 15 June 2024. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Stringer)