Driving westwards along the R62 in the Langkloof of the Eastern Cape, I am struck by the booming agro-industry in this once peaceful backwater. I have been a regular commuter on this road for almost half a century. The ballooning global demand for the Cape’s deciduous fruit has seen a marked increase in hectares under cultivation, packing sheds and informal housing throughout the valley.

Also noticeable is the abysmal quality of the road that serves this export-driven industry, underpins an under-realised ecotourism enterprise and provides an alternative route to the coastal N2 in the event of a road-closing disaster.

It’s the same old uneven, patched and pitiful two-lane road that has received no significant resurfacing or rehabilitation since at least the 1980s.

This winding route traverses several densely populated nodes.

It is burdened by freight- and fruit-bearing trucks, tractors, impatient farmers in bakkies, high-velocity sedans and the crawl-pace jalopies of the poor, not to mention a plethora of pedestrians. Simply stated: it is a dangerous route.

And then, somewhere beyond Misgund, I cross the Great Divide – from the Eastern to the Western Cape – and everything changes.

Here the R62 – newly surfaced for the second time since 2009 – provides a smooth drive, hard shoulders and a well-managed road reserve.

The lay-bys are clean and welcoming; an ideal spot for a stretch and a rest, unlike those in the Eastern Cape, which are repulsively filthy.

The Great Divide — the contrast between Western Cape and Eastern Cape roads is startling. (Photo: Richard Cowling)

The Great Divide — the contrast between Western Cape and Eastern Cape roads is startling. (Photo: Richard Cowling)

Roadside garbage on the R62 in the Eastern Cape. (Photo: Richard Cowling)

Roadside garbage on the R62 in the Eastern Cape. (Photo: Richard Cowling)

The R62 in the Western Cape is maintained by the Western Cape Mobility Department (WCMD), as are all provincial, regional and minor roads in the province.

In the Eastern Cape, the responsible authority for maintaining the R62 is the South African National Roads Agency (Sanral). Indeed, this agency maintains almost all the provincial roads in the province as well as all its national routes. This relieves the provincial authority, the Eastern Cape Department of Transport (ECDT), of a huge maintenance burden.

In 2021, Sanral spent R3.1-billion on road maintenance in the Eastern Cape.

However, almost all of this was allocated to roads in the eastern parts of the province, where economic activity, other than government services and trade, is subdued at best.

Here, extensive livestock farming prevails on private lands and minimal economic output characterises communal lands, where medieval land tenure policies constrain meaningful rural development.

When it comes to the ECDT-maintained regional routes, the geographical bias is even worse.

For example, in the Kouga Municipality – which, after the Nelson Mandela Bay and Buffalo City metros, has by far the largest gross geographic product in the Eastern Cape – none of these regional roads has received a significant upgrade in the past 20 years, and maintenance is confined to filling the odd pothole.

There is no funding for the maintenance of road verges, which are overgrown and littered.

These regional routes (R102, R330, R331) service the growing residential and tourism nodes of Jeffreys Bay and St Francis Bay, large dairy and fruit agro-enterprises, and a burgeoning renewable energy infrastructure. Yet ECDT focuses almost all its investment in the economically moribund far east of the province. Why is that?

Across the border in the Western Cape, the provincial government has done an excellent job in upgrading and maintaining the much larger network of roads under its jurisdiction.

Go anywhere in the province and you will encounter world-class roads.

In the 2021/22 year, the WCMD resealed 2.78 million square metres and rehabilitated 643,000m2 of sealed road; corresponding figures for the ECDT were 15,000m2 and 127,000m2.

The transport infrastructure budget for the Western Cape was R3.4-billion and for the Eastern Cape R2.1-billion, the latter allocated almost entirely to the maintenance of regional and minor roads, since Sanral funds and implements the maintenance of most provincial roads.

It might be assumed that ECDT is spending more than the WCMD on the maintenance of gravel roads, given the extensive network of unsealed roads in the Eastern Cape. But this is not the case.

In 2021, the WCMD re-gravelled and bladed more than double the length of unsealed roads than the ECDT.

The only area where the ECDT outperformed the WCMD was in patching sealed roads, where it filled 4.4 times the area of potholes – a consequence of the poor state of the roads managed by this agency.

The difference in terms of cost-effectiveness of road maintenance between the Eastern and Western Cape provinces is mind-boggling.

It’s no surprise then that other agencies are assuming responsibility where the ECDT falls short.

The Kouga Municipality, which has been governed by the Democratic Alliance for the past two election cycles, offered to rehabilitate the dilapidated section of R330 that traverses the bustling town of Humansdorp; this offer was turned down by the ECDT with no explanation given.

In the Gamtoos Valley, a productive citrus- and vegetable-growing region, the organisation responsible for irrigation services in the valley (Gamtoos Irrigation Board) manages road verges and fills potholes on 94km of the R330 and R331.

Woodlands Dairy and the Cape St Francis Civics Association fund verge maintenance on portions of the R330 to reduce the fire hazard and remove unsightly litter.

At the municipal level, the contrast between the two provinces is even greater.

DA-run municipalities in the Western Cape have by and large an acceptable road network. In most Eastern Cape towns, sealed roads are collapsing into rutted, potholed wrecks that are barely traversable by ordinary vehicles.

Perhaps one of the most bizarre local government-led road rehabilitation projects in the Eastern Cape is the Blue Crane Route Municipality’s plan to seal 158km of the R335 between Somerset East and the Addo Elephant National Park.

It is very difficult to get reliable information on this project.

The 2013/2014 Integrated Development Plan (IDP) for the municipality tells of a project designed to promote tourism by linking Somerset East to Addo via this route, despite there being a perfectly good, sealed-road route via the N10 that is only 16km longer.

According to the IDP, R144-million was allocated to the project via the Blue Crane Development Agency.

To date, about 15km has been sealed, literally in the middle of nowhere.

Other municipal documents reveal that this is a “long-term” project that faces “environmental challenges” and is “on hold”.

A 28km section of the intended route is a gruelling 4x4 track, most of it in the Addo park. Rehabilitating and sealing this road would likely cost billions and would be subject to hugely stringent environmental constraints, should SANParks ever sanction such a hare-brained project. There is a story here that needs further investigation.

The striking difference in road maintenance and quality across this “Great Divide” is a metaphor for different styles of governance in the two provinces: good in the Western Cape and bad in the Eastern Cape.

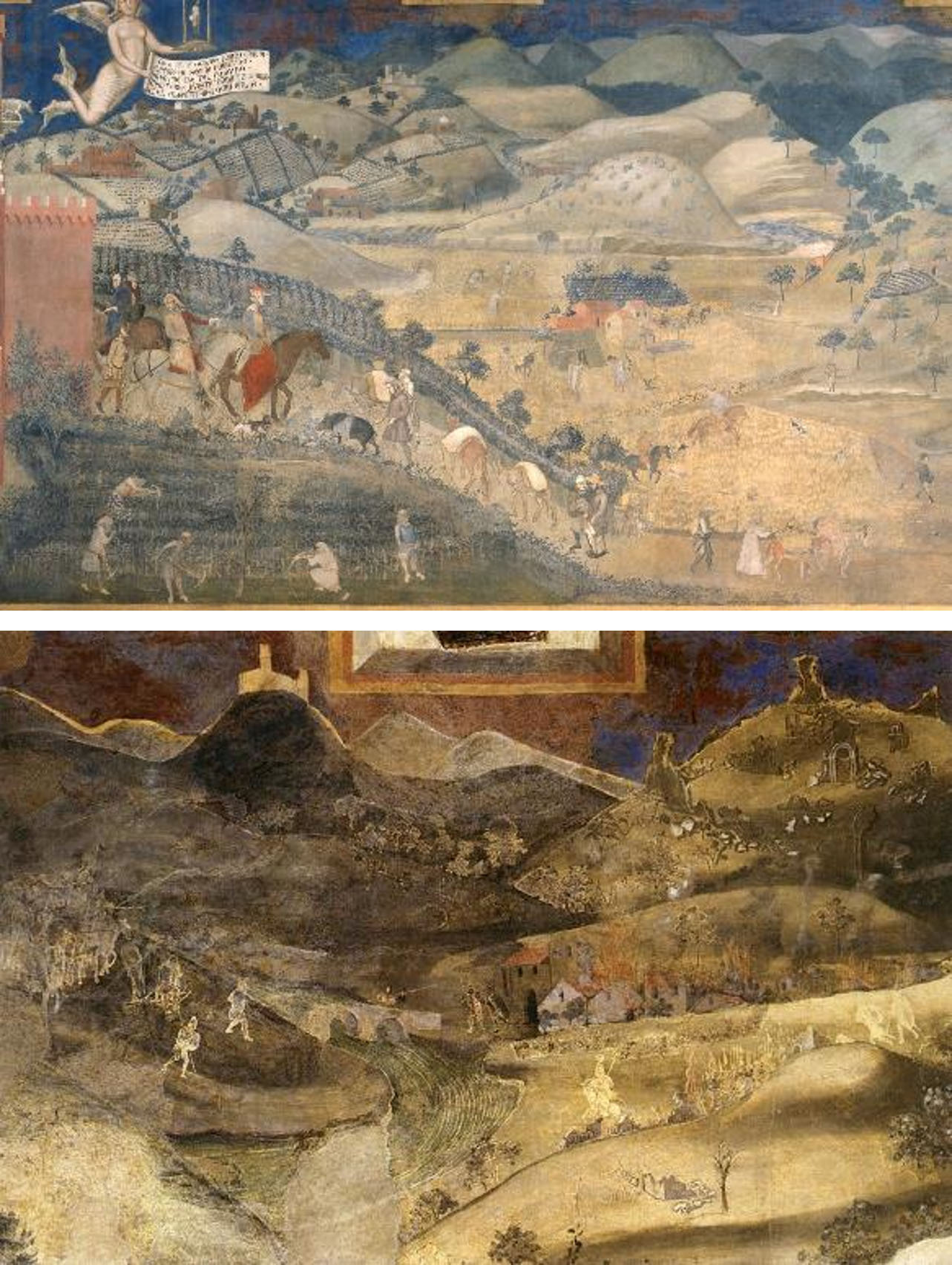

Way back in 1338, the Italian Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted six fresco panels in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico (town hall), titled, *The Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government. The frescoes illustrate four scenarios: good and bad governance in rural and urban contexts.

The lessons are as starkly evident to us now as they were to the nine councillors who governed from Siena’s town hall in the 14th century.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti fresco panels in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico. (Images: Supplied)

Ambrogio Lorenzetti fresco panels in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico. (Images: Supplied)

Bad governance leads to crime, corruption, poverty, famine, environmental degradation and war; good governance produces prosperity, security, judicious land use, productive agriculture and good infrastructure.

As a reflection of good governance, the WCMD has obtained its 10th consecutive clean audit report and spent 98.8% of its allocated budget for the 2021/22 reporting year.

The same cannot be said of the ECDT; for example, the Transport Infrastructure directorate responsible for road maintenance incurred R385-million of irregular expenditure in 2021/22.

By all means, invest in the roads of the eastern reaches of the Eastern Cape, but then link this to land tenure reform that can unleash the productive potential and entrepreneurial might of the people of this well-watered and fertile part of the province.

But don’t do this at the expense of much-needed investment in the economically productive western parts of the region, where sustainable jobs are at stake.

The geographic bias in road infrastructure investment in the province is all about short-term job creation and crony empowerment as a means of garnering votes for the ruling party.

It is unwise and unpatriotic.

One day, certainly not in my lifetime, the governance differential across the two provinces might be reduced or even eradicated.

This would require political leadership in the Eastern Cape that can prioritise competence over cronyism, economically sensible investment over pork-barrel patronage, and the common good over political self-interest.

The odds of this coming from the ANC are infinitesimally low. DM

*Thanks to Brian Huntley for introducing me to Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s fresco.