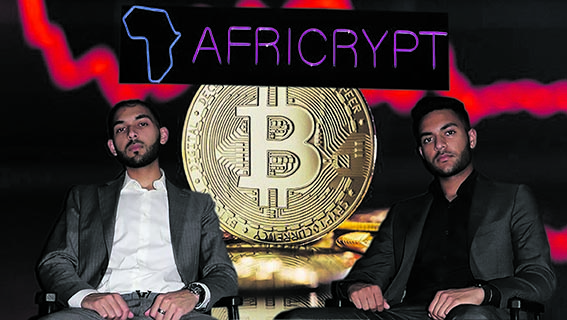

They disappeared with billions, left regulators flat-footed and triggered one of the biggest financial implosions in South African history. But the Cajee brothers never really vanished and the full truth about Africrypt, one of the largest cryptocurrency scams ever perpetrated in South Africa, has never really come to light.

In April 2021, Africrypt, a cryptocurrency investment platform run by brothers Raees and Ameer Cajee, collapsed abruptly. What followed was one of the most dramatic implosions in South Africa’s financial history: R3.6-billion vanished overnight, leaving thousands of investors without funds and an abundance of unanswered questions, with the brothers disappearing into a regulatory vacuum which allowed them to evade accountability for over two years – this is how it happened.

“It was a centralised system pretending to be decentralised,” cryptocurrency analyst Wiehann Olivier told Daily. “There was no oversight, no third-party security testing and no asset segregation.”

Make a promise or make a wish?

Africrypt launched in 2019, with the Cajee brothers – then 20 and 17 – marketing themselves as prodigious crypto entrepreneurs. Their pitch was simple but seductive: returns of up to 10% per day, enabled by proprietary trading algorithms and arbitrage systems.

While their youth and such promised returns may seem laughable now, at the time, with less public understanding of the crypto market and even greater volatility, their youth and apparent expertise could almost be seen to lend credence to their claims, as did their social media presence, which flaunted designer clothes and international travel.

Also convenient to the timing of the platform’s launch was the Covid-19 pandemic, which left many of the middle-class working remotely, watching stock market drama such as the incredible peaks and troughs around Gamestop trading and a crypto boom – all lending credibility to the Cajees’ claims.

By 2020, they claimed to manage hundreds of millions of rands across thousands of client accounts. The reality is that Africrypt was structurally opaque; there were no audited statements, external custodians or formal financial licensing. As later legal filings and investor testimony revealed, the Cajees retained complete control over the platform’s wallet infrastructure and funds.

“The entire operation was built on trust and perception,” said one large-scale investor, who developed a close relationship with the Cajees, and wished to remain anonymous. “There were no compliance processes, no separation of accounts - client money was pooled and moved at will” – including into their personal accounts.

Read more: South Africa Bitcoin ‘Ponzi’ Scheme Out of Regulator’s Reach

Exit, staged, left

On 13 April 2021, Africrypt investors received an email claiming the platform had been hacked – commonplace in crypto rug pulls – urging users not to report the incident to authorities, warning that this might compromise recovery efforts.

“Our system, client accounts, client wallets and nodes were all compromised,” Ameer Cajee said in the email. Within days, the company’s website was shut down, its Durban offices were emptied, and its known phone numbers stopped working.

The Cajee brothers appeared to have dropped off the face of the earth. In reality, they’d taken their ill-gotten funds and removed themselves first to the United Kingdom, then Dubai.

Blockchain analysts quickly noted inconsistencies at the time; instead of signs of an external breach, transaction data suggested internal wallet movements consistent with a classic rug pull. A rug pull occurs when someone solicits funds with promises of high returns and then does a runner with the money. Funds were split into smaller amounts, mixed through obfuscation tools, and routed through offshore exchanges.

Initial reports claimed losses of R54-billion – a number based on a misidentified wallet linked to South African cryptocurrency exchange Luno, but court-appointed liquidators would later confirm the real loss: R3.6-billion, based on investor records, bank transfers and blockchain analysis.

Inside an escape plan

Despite the magnitude of the theft, no formal criminal charges were brought against the Cajees. Investors scrambled to appoint lawyers and forensic investigators, but the brothers stayed ahead of the fallout.

Whistleblower emails and court records show that while public-facing communications had ceased, backend access to wallets and server infrastructure remained active for days after the alleged hack. In that window, whistleblower data obtained by Daily Maverick indicates that the remaining funds were siphoned and laundered through privacy-centric tools.

Internal access logs also viewed by Daily Maverick show that known Cajee device IDs remained logged into administrative platforms during this period – a crucial red flag and a clear contradiction of the platform being hacked.

Meanwhile, Raees and Ameer used family members and offshore intermediaries to move funds and shield assets. Their operations were run through a patchwork of nominee directors, VPN-encrypted routing and difficult-to-trace crypto accounts.

“When you control both the platform and the wallets, and you’re operating in a regulatory void, you can act with total impunity,” Olivier said.

Regulations? What regulations?

Despite mounting investor complaints, the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA) refused to launch a full investigation. In a public statement issued on 24 June 2021, the FSCA said: “At this stage, we do not regulate crypto assets and therefore the FSCA is not in a position to take any regulatory action.”

The Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC) also declined to act. Without a registered accountable institution or licensing requirement for crypto platforms, there was no formal KYC (Know Your Customer) oversight or transaction reporting channel.

“The FSCA and FIC were paralysed by a legal grey zone,” Olivier told Daily Maverick. “And that paralysis gave operators like Africrypt the perfect cover.”

Legal grey zone exploited

The Africrypt model relied on centralised custody, with investors sending money to accounts controlled directly by the Cajees, believing it would be stored or traded on their behalf – not entirely dissimilar to the methodology of platforms such as Satrix, but with zero oversight.

Whistleblower documents indicate that incoming funds were first routed through bank accounts belonging to personal or trust structures, rather than a corporate custodial account. This blurred the legal line between client capital and operator revenue – a strategy that later complicated legal recovery efforts.

No disclosures were provided to clients. No investor agreements were standardised. Africrypt had no FSCA registration, no FIC status and no linkages to South African Reserve Bank-monitored systems.

In short, the Cajees built a shadow exchange – accepting deposits and executing transactions while avoiding every requirement that would apply to a traditional financial institution.

“They essentially recreated a bank without any of the obligations that come with banking,” Olivier said. “And because it was crypto, everyone thought the rules didn’t apply.” At the time, they didn’t.

Settlement, but no justice

By mid-2021, one investor – Juan Meyer, CEO of Aurum Wealth – launched legal action against Africrypt, alleging that R177-million in client and personal funds had been stolen. Court papers revealed that Africrypt had failed to separate client and operational accounts, and that key wallet access was retained solely by the Cajees.

In late 2021, an anonymous settlement offer was tabled: investors who withdrew criminal charges would receive 61 cents in the rand. While some accepted, Meyer declined and liquidation proceedings continued.

A year later, Swiss authorities detained Ameer Cajee in Zurich on suspicion of money laundering and asset concealment, with Ameer having allegedly been in the country to access Trezor wallets – physical wallets on which the brothers had stored stolen Bitcoin.

He was placed under supervised release reportedly in a luxury hotel, which reportedly cost $1,000 per night. Swiss prosecutors later withdrew the case against Ameer Cajee. While no official explanation was published, legal insiders and leaked correspondence suggest that the decision followed the withdrawal of key investor complaints tied to settlement agreements. Ameer was released on bail, with no further prosecutions following.

Our old South African aphorism: ‘and then?’

To date, most investors have not been fully compensated, with no confirmed and comprehensive recovery of assets having taken place. And while regulatory frameworks have slowly evolved – with the FSCA now designating crypto as a financial product – gaps still remain.

Read more: South Africa to Demand Crypto Firms be Licensed by Year-End

Meanwhile, neither Raees nor Ameer Cajee has resurfaced publicly. Their digital footprint remains minimal. But behind the scenes, evidence suggests they have maintained access to at least part of the Africrypt infrastructure through proxies, and as our follow-up stories will demonstrate, have not kept their hands clear – or necessarily clean – of other business activities. DM

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R35.