On the day the UK voted to leave the EU seven years ago, a British friend of mine shocked me by saying he was elated at the decision. Just getting free of all those Brussels mandarins would be worth it, he argued. I thought the decision was nuts. We argued in very familiar terms about the pros and cons, with only one way to resolve the argument: we took a bet.

The bet was simple: that the GDP growth of the UK would be lower than that of the EU in the three years following the UK’s actual exit. I honestly thought I had this in the bag. But I just lost the bet.

It’s an odd time to lose a bet like this because the arch-Brexiteer Nigel Farage has just pronounced that he thinks Brexit has failed. Furthermore, the most recent poll shows that almost two-thirds of Brits say the move has been more of a failure than a success. British public opinion has seen an enormous sea change.

From my point of view, the change of opinion was entirely predictable. But actually, it is not so much that Brits think Brexit was the wrong choice (although they do now by a small majority, if you can trust these polls), but that they think the Conservative government has handled the change badly.

The YouGov poll shows 58% of those who voted to leave the EU in 2016 now think the government is handling Britain’s exit from the bloc badly — a figure that rises to 83% among Remain voters.

But the surprising thing is that none of this sentiment is reflected in the numbers, and it is worth asking why that’s the case. It’s not that the UK has flourished following its departure from the EU; it’s just that the economic growth of both the UK and the EU has been a bit sluggish, the EU a bit more so than the UK. Not as sluggish as SA, of course, but that’s a different story.

One obvious reason is that the UK’s departure coincided with the coronavirus pandemic, but in a sense, the pandemic affected all European countries roughly equally.

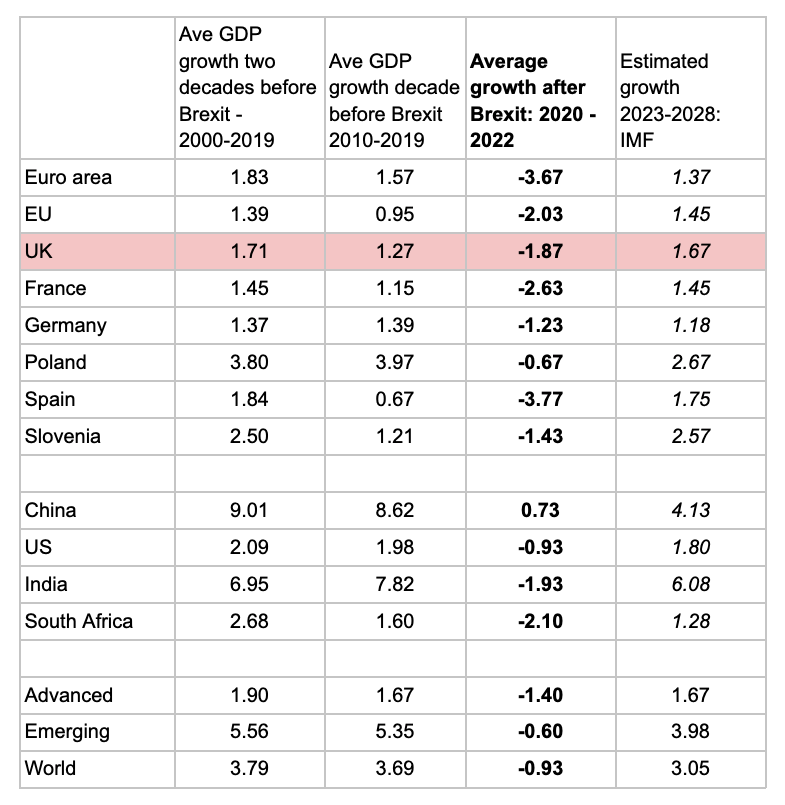

Anyway, here are the numbers: they are drawn from the IMF’s records and included are its predictions for the next five years or so.

I had three reasons for thinking I had the bet in the bag. First, I thought even in the best circumstances, there was bound to be a short-term contraction in the UK as both sides got used to the new way of doing things. Second, I thought it would be very unlikely that the EU would give the UK a decent trade deal since its immediate incentive would be to demonstrate to other wavering countries (hello, France and Italy) that leaving would result in economic pain.

And third, my extensive knowledge of economics led me to believe that easing trade is naturally a boost for all the countries in any given economic bloc. Ergo, exiting would have the opposite effect.

Turns out, in the three years following the UK’s departure in early 2020, the UK’s economy contracted by 1.87% on average, which was a smaller decline than the EU, and a much smaller decline than the euro area. The euro area was growing faster than the UK before its exit, but the EU as a whole was growing more slowly. This was one of the reasons some Brits wanted to leave: they felt the EU was a failing institution and it was crazy to be part of it.

But no sooner had the UK left than the page turned: all of a sudden the broader EU started outperforming the core European countries. It’s also worth noting that although the UK marginally outperformed (a trend the IMF thinks will continue), the UK dream of joining the dynamism and growth of the US economy hasn’t materialised either. And that isn’t expected to change either.

There is one other point (partly because I like being a contrarian): I still think the EU is a fabulous project, a sentiment a huge number of people who live there don’t share. But I support it because I think the incorporation of smaller countries gives them an enormous boost, which is why there are so many countries that are still gagging to join. You can see this in the figures for a larger country, Poland, and a small country, Slovenia. The problem for the EU now is not the small newcomers, it’s the old big countries. (Hello, Germany, Spain and France).

Some of how all of this is turning out does make sense to me, but, you know, I’m absolutely guessing here. Germany’s current woes are in some ways related to the decline of China; Germany’s reliance on trade in physical goods has served the country fabulously over the past decades, but it does make it more vulnerable to the vagaries of fast-growing, big countries like China. The UK’s current surprising relative strength may likewise be related to its greater reliance on the service industry.

Perhaps the most surprising thing is that there are few real surprises: overall, the numbers are pretty close to their previous trends. That makes sense too, if you think about it; services are Europe’s predominant industry now, so trade flows aren’t the differentiator they once were. And all of Europe, the UK included, still does have one huge problem: declining population growth.

What surprises me about this is how little it is discussed within Europe. Maybe it’s just my imagination, or perhaps I just don’t speak enough of Europe’s main languages. SA is also stagnating, but it’s very central to the public debate. It seems to me the big, old countries of Europe, the UK included, are looking a bit wobbly, and therein lies some big problems for the future.

For all the agonies and arguments, for all the pages of newsprint expended on the subject, Brexit doesn’t seem to have made a noticeable difference, either positively or negatively, to either side. It’s weird. DM

Business Maverick

After the Bell: Arch-Brexiteer Farage thinks Brexit has failed — is he still wrong?