It’s hard to think of a sadder and more triumphant singer than Johnny Cash. He was a country singer long before the category established itself but gradually became an icon across genres, ending his career singing a set of searing pop songs against a sparse background in his famously deep and croaky voice.

For sheer visceral emotional exposure, it’s hard to get more personal than his cover of the Nine Inch Nails song, Hurt.

Yet he wasn’t always a figure of empathy and was often something of a contradiction, even at one point singing a lighthearted novelty song, A Boy Named Sue (he hated the song).

He was both a voice for the ordinary man and, famously, a highlight of his career was singing to the inmates of Folsom Prison. He was also personally haunted, leading to a very pop star-ish drug addiction.

Like so many famous people, he was a contradiction, but unlike many famous people, he cleaved towards an ordinary life.

There’s a scene in the movie about his life that starred Joaquin Phoenix as Cash and Reese Witherspoon as June Carter, in which she gets infuriated at the band’s disorganisation before a concert. As she turned on her heel and marched out, she spat out at the band (if I remember correctly), “You know your problem is ... you don’t walk the line.”

And that pronouncement became the chorus line of Cash’s most famous and bestselling song, I Walk the Line. The song is about responsibility and duty and shouldering the burden, however heavy it might be.

In fact, the movie did not portray the real origin of the song. Cash wrote it after meeting and falling in love with June Carter, but he was also married and seemingly trying to convince himself to stay on the path.

“Because you’re mine, I walk the line.” It’s both a love song and a curse.

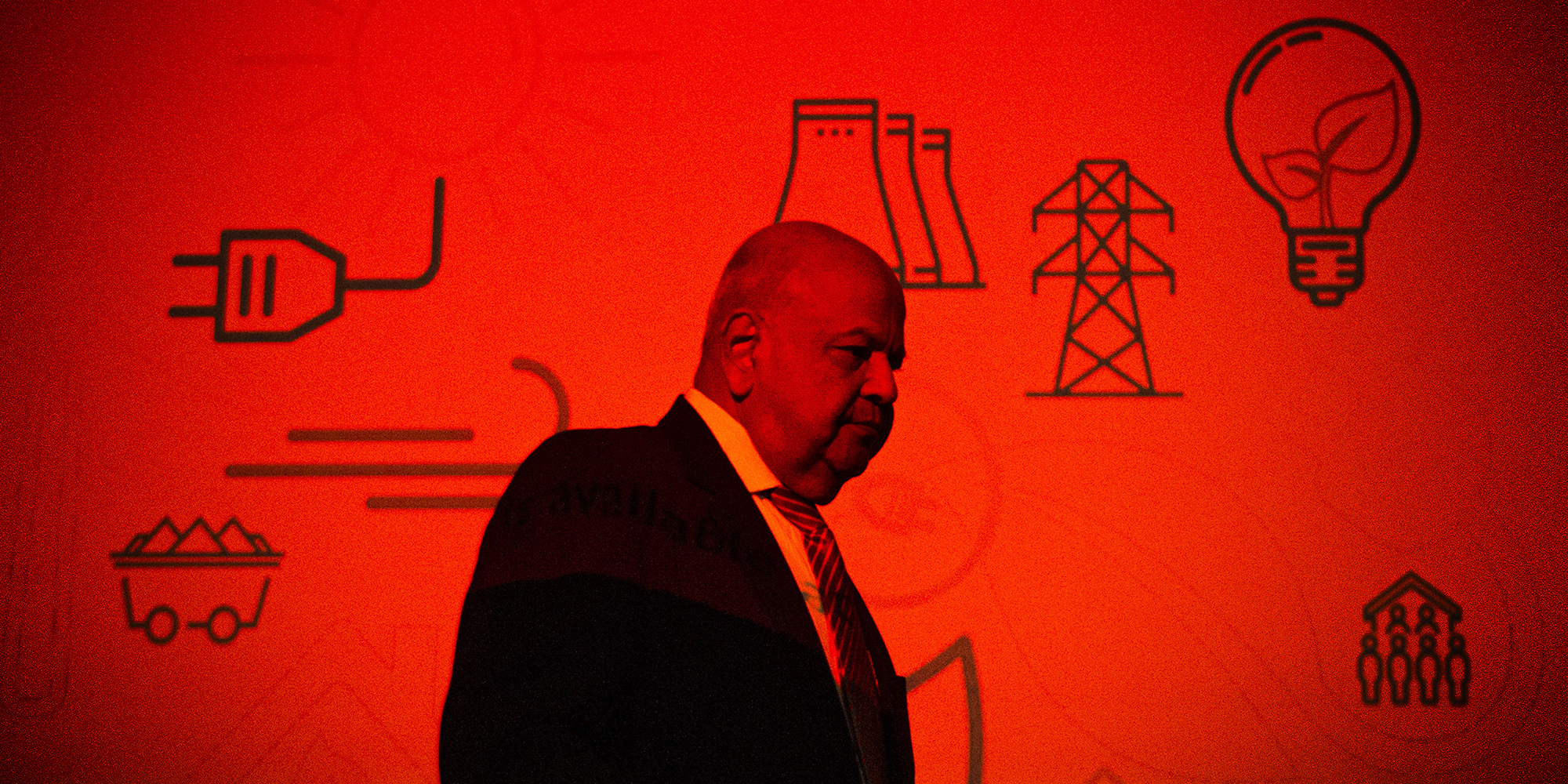

If there is any politician who reminds me of Johnny Cash – his career, his contradictions, his triumphant sadness – it’s Pravin Gordhan, who intends to hang up his gloves after an extraordinary career as an activist and a politician.

It must be said – and it’s unfortunate – that he leaves politics at a personal and political low point.

His last function as public enterprises minister has arguably been a disaster. Eskom is producing less electricity every year; SAA remains insolvent; Transnet has just fired the CEO, whose appointment he oversaw; the SA Post Office is bankrupt and so is the Land Bank. It just goes on and on.

It’s a wall-to-wall catastrophe.

How much of this is Gordhan’s fault is debatable. He had a reputation as a meddler and as someone who didn’t consider the CEOs of public enterprises any different from one of his deputies in the ministry. They were, as far as he was concerned, under the jurisdiction of the political system and therefore subject to its requirements.

Consequently, the CEOs of public enterprises, under his watch, were constrained from doing anything as outrageous as right-sizing the staff complement, heaven forbid, which could anger government union supporters.

In his book Truth to Power, former Eskom CEO André de Ruyter said Gordhan supported what he called an “activist board”. This was essentially “a peculiar governance construct” called an “engaged board” based on an old Harvard Business Review article.

What that meant in practice was that instructions were given by board members directly to people several levels below the executives – without informing line managers.

The board required reams of information and wanted to get involved in outage management and issues of plant management without really knowing much about either.

Gordhan was, in his later years as a politician, understandably torn by his long-standing belief in communism and the requirements of the modern era.

It’s never been clear whether or not he was in favour of public sector involvement in state-owned enterprises. And that’s despite President Cyril Ramaphosa repeatedly stating that this was the new policy of the government.

He certainly wasn’t a supporter when the SA Communist Party, Gordhan included, decided to throw in its lot with Jacob Zuma and forcibly remove the more modernist and irritatingly successful government of Thabo Mbeki, of which he was then part.

He came, as we all know, to rue that moment when he was fired by Zuma, not once but twice, essentially for not doing the bidding of the Guptas, we later learnt.

Gordhan became famous for instructing others to “join the dots” but, you know, the weird thing was that he never did so himself, or at least not in a way that would have caused a major breach. He remained a dutiful, diligent, disciplined member of the party, taking on new functions with vigour and staying in the fight.

And what a fight it was.

SA has many people to thank for the fact that the State Capture effort largely failed, but one of its major impediments was Gordhan, whose decision not to walk away, to play his cards carefully and deliberately, and to stick it out for the long game, was an important factor in limiting the damage.

Among the important skills Gordhan commanded (and I remember this from way back during the UDF days when I was a student activist and Gordhan was a UDF organiser in Durban) were subtlety and organisation. He’s always been a plotter by nature and sometimes by function, notably during the infamous Operation Vula.

And those skills were most evident during his inestimable spell as SA Revenue Service (SARS) commissioner. His dedication and functional literacy came to prominence at SARS.

SA suddenly became one of the first countries in the world to permit e-filing, for example.

SARS was transparently and sensibly run for decades, eventually becoming a crucial impediment that had to be overturned by the Radical Economic Transformation faction – and it was.

But under Gordhan’s leadership, year after year, SARS produced more tax for the government than budgeted. Sometimes so much so, that it was virtually an embarrassment to a government for whom social spending was such an important policy principle.

His years as finance minister were – I don’t know how best to put it – peculiar. He seemed both at home and at odds with the job.

In his interactions with business, he would often castigate company owners by pointedly asking them what they had done to promote democracy, address poverty, correct society’s evils and so on. It never seemed to occur to him that business success is rooted in being excellent at what it does rather than being good at what he wanted it to do, which was to be a kind of ANC government proxy and support system.

There was a palpable cultural difference. But there was also no lack of respect, so business, rather meekly, in my opinion, rolled with his tax increases, his low-key hostility and his ideological chastisement of wealth.

Yet for sheer endurance, dexterity and intellectual heft, he has no comparator in SA’s democratic period.

He might have been torn at points, but when all is said and done, he walked the line. Respect. DM

Business Maverick

After the Bell: Like Johnny Cash, Pravin Gordhan walked the line