Bloggers, YouTube pundits and prognosticators of every description have been all over this election, sometimes massively outperforming even very large media outlets. More on that later.

But prediction markets have also really exploded over the past few years and are now beginning to have an influence, so it’s worth looking at how successful - or unsuccessful - they have been. The short answer is that while they have been erratic, they were remarkably accurate in predicting the election results, although they missed some important issues.

It’s not the first time prediction markets have operated in a US election but, up till now, they have been extremely local and small. The University of Iowa has run something called the Iowa Electronic Markets (IEM) for years, but it is run essentially as an academic research experiment. Oddly, for the world’s most capitalist country, political prediction markets are heavily restricted in the US.

The reason is twofold, both of them kinda dubious. At a federal level, the US has strict anti-gambling laws and the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006, which is actually aimed at online poker, makes it difficult to operate a prediction market at a national level.

In addition, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), which regulates commodity markets in the US, has consistently rejected proposals to legalise real-money political prediction markets. It argues that they don’t serve a legitimate hedging purpose, which is a key criterion for CFTC-approved markets. The IEM operates with a specific limited exception granted by the CFTC.

The problem with these limits is obvious; in a sense, they are protecting their own turf. The existing gambling industry in the US lives in dire fear that gambling will move online, and rightly so because this is a huge threat that is gradually becoming a reality. The CFTC also has turf to protect, although it’s less clear. But if you allow political prediction markets, someone will soon want to trade other stuff and the CFTC presumably wants to nip that in the bud.

In many places around the world, political prediction markets are allowed; the largest is Polymarket, which, by the way, makes you swear you are not a US citizen as you sign up. But Polymarket facilitated $3.1-billion in trades related to the US presidential election and captured about 85% of the global market share in election-betting.

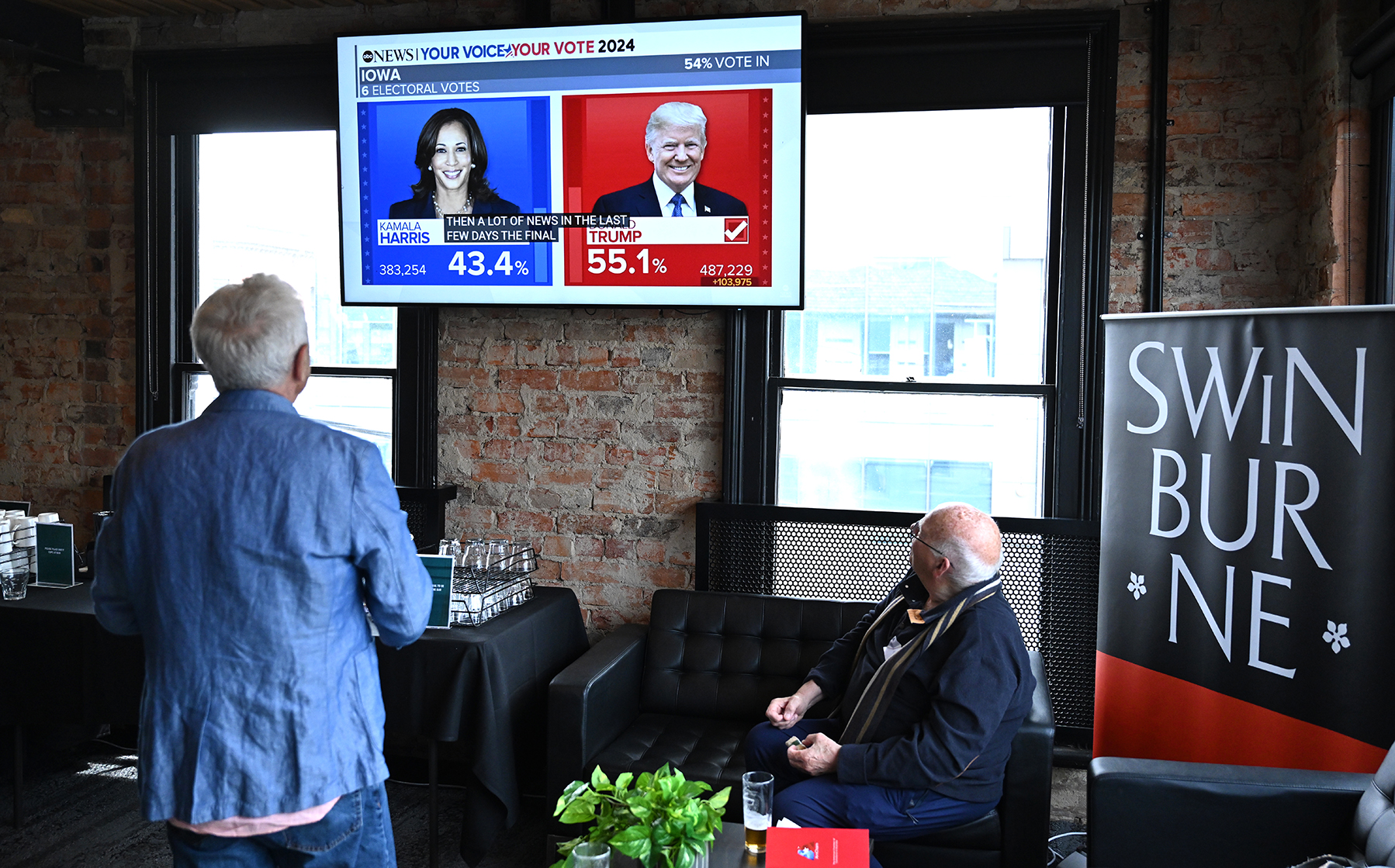

So, how did they do? In short, amazingly well and what they got indisputably right was the winner: Mr D Trump Esq. And, interestingly, they were massively more accurate than the pollsters, who were predicting a dead heat right up until the last minute. Just compare these graphs:

On the day before the election, Polymarket was giving Trump a 58% chance of winning. Compare this with an average of multiple polls, which were calling it all square and giving Trump a 10 percentage point lower chance of winning. Well, we know who we will trust from now on. Kalshi’s market followed the same pattern.

Interestingly, no lesser publication than Fortune magazine fell into a trap regarding Polymarket, heavily implying that the bets on the site were being manipulated because “analysts at two crypto research firms have found evidence of rampant wash trading on Polymarket”.

The fear of market manipulation is one of the main reasons often cited for not trusting prediction markets - and here it was happening before our very eyes! Wash trading sometimes happens, particularly in unregulated markets, where participants both buy and sell shares at the same time, creating a false sense of high volume. That, in turn, suggests high volume in the market which tends to underpin the price. The Wall Street Journal eventually tracked down the trader, who said he had no political agenda; he just wanted to make money. Which he did!

One interesting thing about the comparison is that the polling average shows Trump dramatically losing support at the time of the only presidential debate between Trump and Harris. But the prediction market showed only a small change, which is historically accurate: debate winners get a bump, but it doesn’t last. The polls did show Trump’s support building towards the end of the campaign, as the prediction market did, but they didn’t show Harris’ decline until very late and not strongly enough.

So, the question is: Why did this prediction market get it right? Other prediction markets, like Manifold, also generally called it, but were more scatty. The answer was provided a long time ago by author James Surowiecki in his book, The Wisdom of Crowds, which is a classic in this field. Surowiecki made the general point that markets work because they measure not what you want to happen but what you honestly think will happen. It helps that often they are binary; you are either wrong or right.

Surowiecki goes much further than this, pointing out that there are situations where crowds are utterly and sometimes dangerously wrong. This is something called “herd behaviour”, which is a widespread social behavioural pattern within a specific group. But these are typically small homogeneous groups.

For the wisdom of crowds to work, you need large, heterogeneous groups that contain independent thinkers and offer concrete gains. It’s noteworthy, for example, that Polymarket is a real-money market and Manifold, which was less accurate, is a fictitious money market (although that is changing).

Anyway, my prediction here, which will come as absolutely no surprise, is that prediction markets’ time has come and no future election will ignore them. DM

Tim Cohen blogs at timcohen.co.za

Business Maverick

After the Bell: The US election and the wisdom of prediction markets

Outside of the actual poll result, I suspect the 2024 US election will be remembered for two things: the new influence of bloggers; and the importance of prediction markets.