What do you do if there is something you want but can’t afford? We all face this problem nearly every day. Personally, my preferred solution is to find an appropriate person or circumstance to blame for this inadequacy, because naturally, the world owes me the desirable object. The fact that I don’t have it means someone or something is at fault. Obvs.

There are other possible solutions. One is to convince myself that I can afford it. You can achieve this by ignoring your bank statement. A version of this “solution” is to claim that although I can’t afford it now, I may well be able to afford it in the future. So, I might as well just go ahead and buy it now because, in time, it won’t break my piggy bank.

There are still other approaches. One is to indignantly claim that because there are people out there suggesting you can’t afford it, they are the ones who are delusional, or even worse, deliberately self-serving and mendacious and determined to prove me wrong. Their private interests impel them to falsely claim that the object of my desires is unaffordable. The fact that they suggest it’s unaffordable is enough (for me) to believe that it is affordable.

The more you think about it, the more ways you can justify your expenses. In my youth, anything my friends had was naturally owed to me, otherwise, the world was being “unfair”. The argument has a high-mindedness which tends to obscure the possible counterargument that I, or my parents, couldn’t afford it.

Oblivious

I know this is all slightly childish, and yet, in respect of the new National Health Insurance Bill (soon-to-be Act), we have heard versions of all of the arguments above. Simply put, the arguments in favour of the NHI system are oblivious to the facts of South Africa today. (I should say the parties in opposition to the NHI system as proposed — not as it happens, national health insurance in principle — are also oblivious in some respects, but I’ll get to that in a moment.)

On Monday, the head of SA’s largest healthcare scheme, Adrian Gore, provided an analysis of the finances required to activate the NHI scheme in SA, explaining for the nth time why a national health insurance scheme as envisaged cannot work in SA now.

He and other healthcare insurance providers, who are all now staring extinction in the face, have made these arguments endlessly to the health department and politicians generally. I’ve heard some of these arguments before, but even so, on the eve of the legislation becoming law, it was interesting to hear an informed voice, familiar with the issues, running through the arguments, yet again.

The basic problem is this: we are who we are. There is no getting around that. South Africa is a medium-income, highly unequal society, in which there has been no real economic growth for more than a decade. Why does that make NHI, as envisaged, unimplementable?

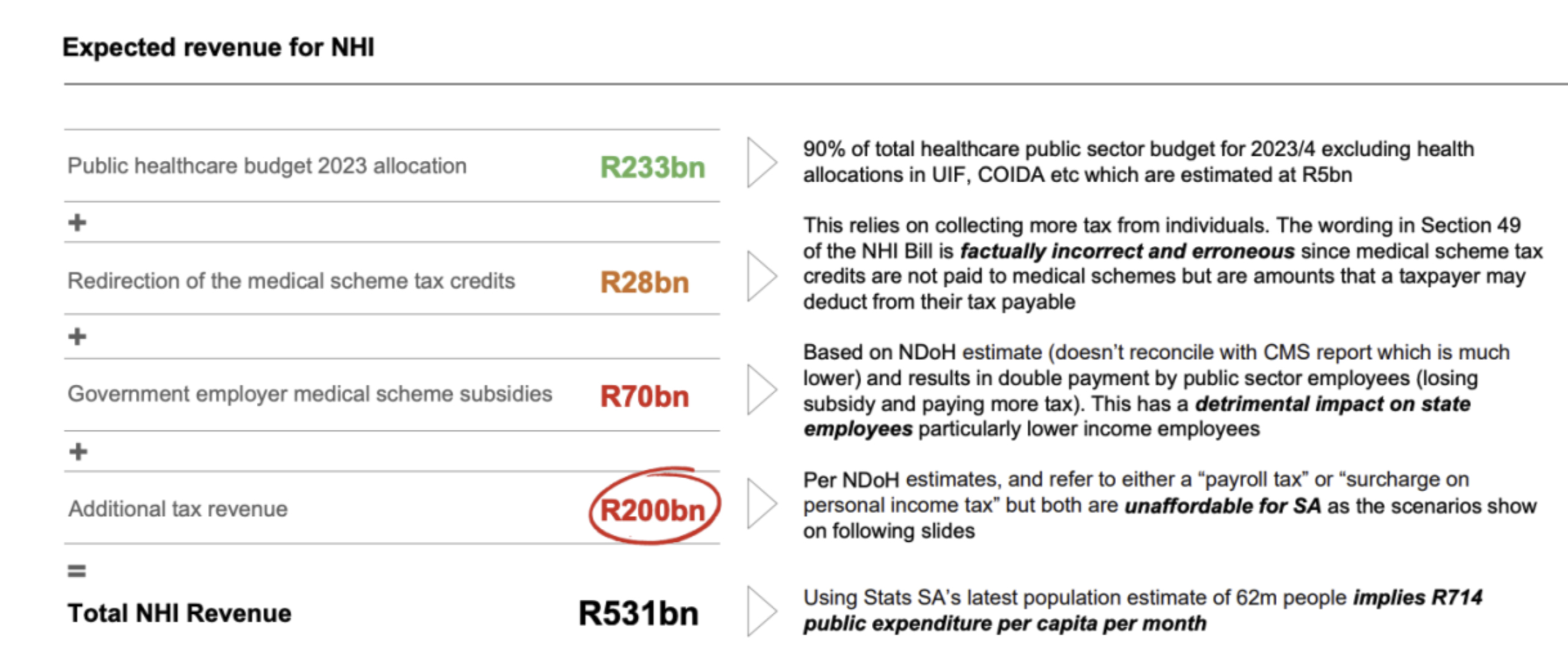

Well, we don’t actually know what the financial basis for the new NHI will be, because the Bill is being passed without clear financial modelling and there is a reason for that: the financial truth is too hard to contemplate. See the unaffordability argument above. But, says Gore, let’s assume that the NHI uses what is currently available. What you get is the following breakdown:

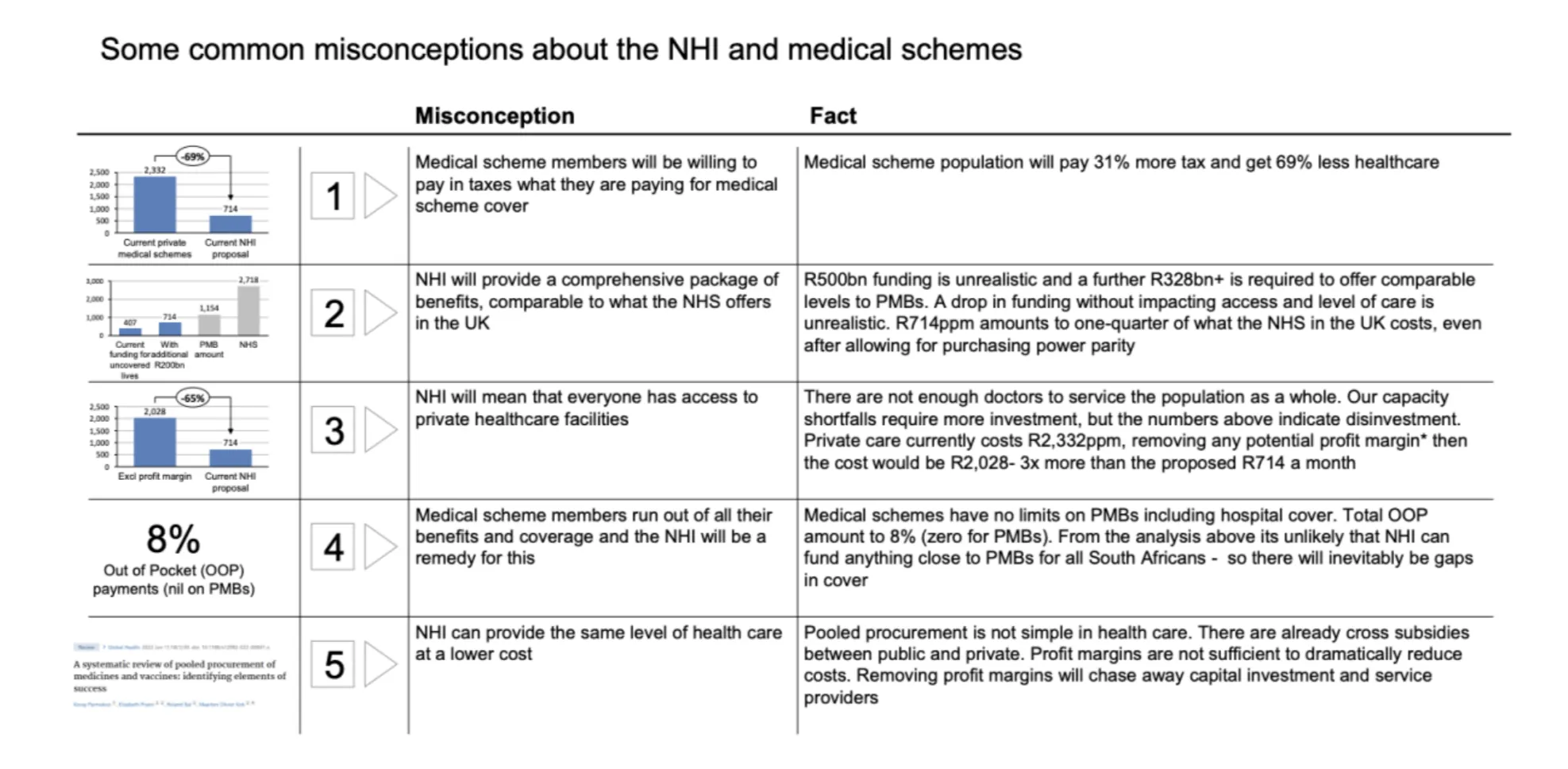

The NHI legislation appears to assume that what it will have available will be in the order of R531-billion in current money. Fine. But this includes an extra R200-billion in new taxes. To get that, VAT will have to go up by 6.5 percentage points, or personal tax will increase by 31% or payroll tax (currently UIF contributions), will have to increase tenfold. I am not making this up.

Gore didn’t say this, but allow me to add: The government is working on the assumption that people paying for private healthcare now will be happy to hand over what they currently pay to the government. Trust me, this is not true. But in their minds, that would cover roughly the R200-billion shortfall and means that net-net, these people will be in the same position from an income point of view as they are now; they would just be paying for healthcare to a different entity.

Of course, from a healthcare point of view, they would be getting a lesser service, but it would be the same service everyone gets, so it would be fair.

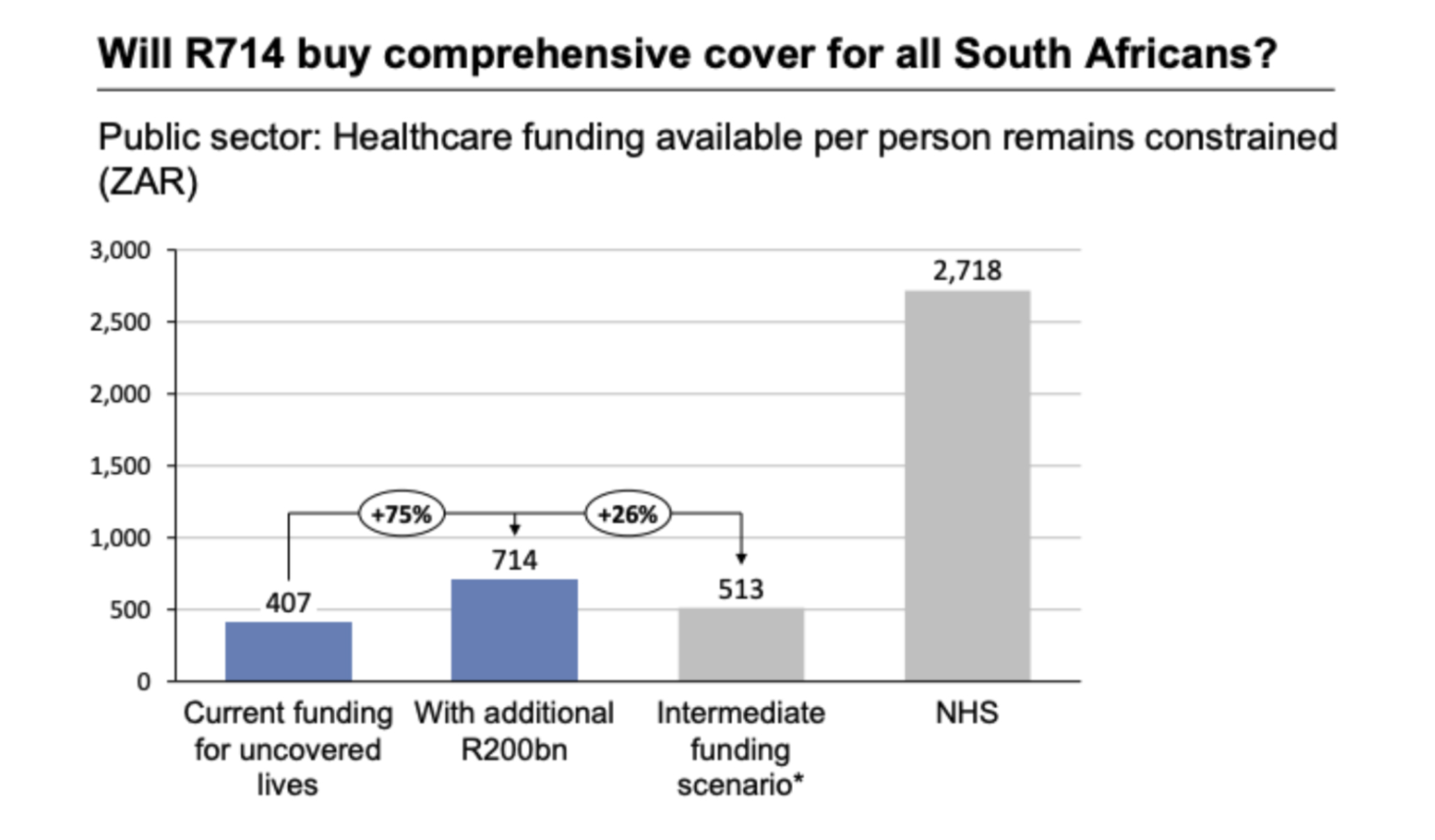

But Gore asks an additional question: what kind of healthcare will this provide South Africans? What we will get is an average expenditure of R714 per person per month. That is substantially less than the Prescribed Minimum Benefits, which healthcare insurance companies are required to cover, of R1,154 pp/pm.

“There is no evidence to show that R714 pp/pm can purchase ‘comprehensive health care services’ contemplated in the NHI Bill,” Gore says. At the current prescribed minimum benefits level, the tax increase would be in the order of R528-billion, or an 82% increase in personal income tax.

What about the lucky people who do have health insurance now? What will they get?

“The medical scheme population will pay 31% more tax and get 69% less healthcare, including a significant portion of pensioners with the highest healthcare needs,” Gore says. That includes public servants, BTW.

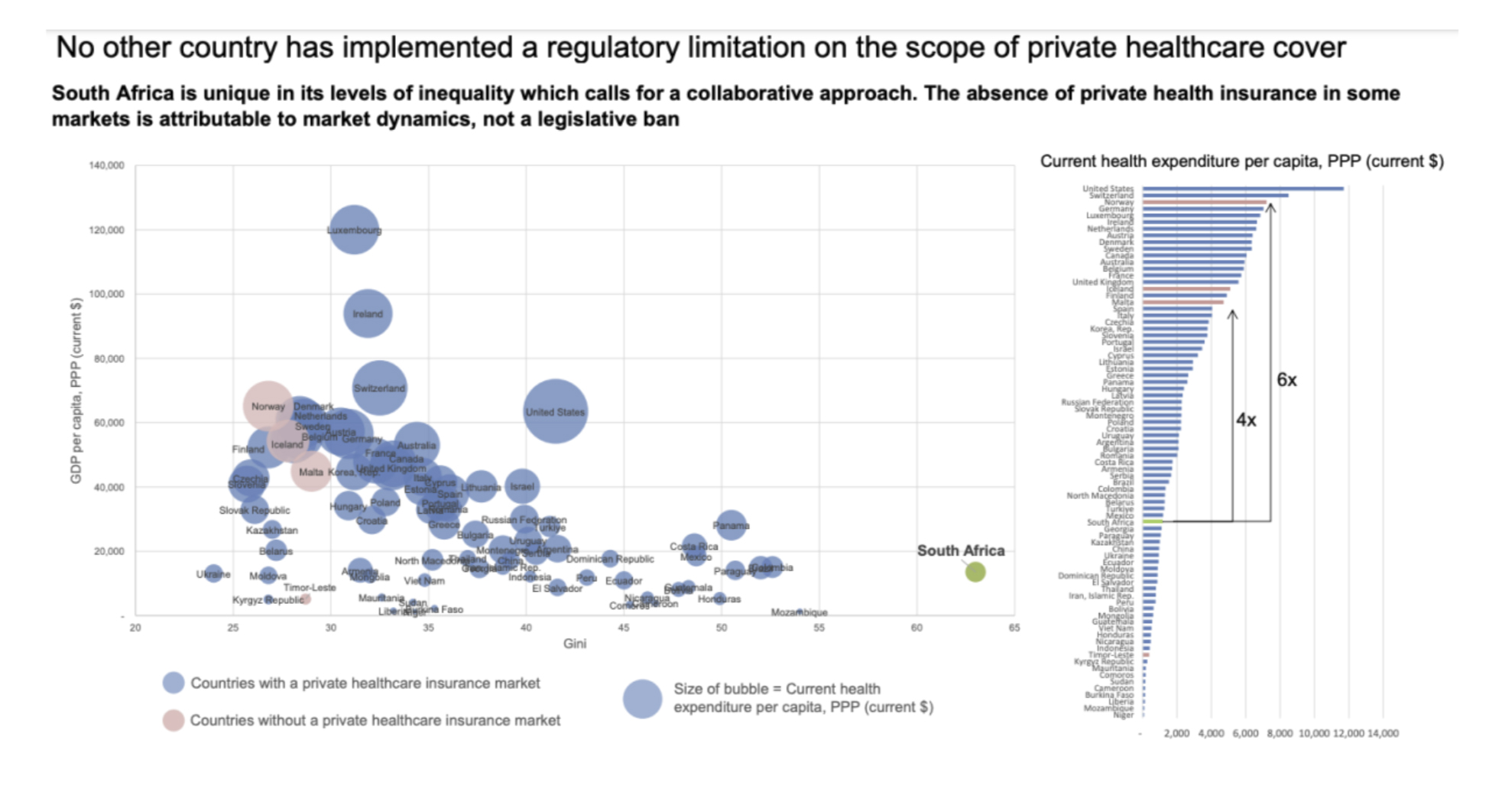

There are countries which offer national health insurance without any additional support from the public sector: these are fewer than people think. Almost all countries allow a private sector supplement. Discovery says there are 17 countries that don’t allow any private sector involvement, as opposed to 169 countries that do. Those that can get by without private healthcare are generally rich nations without huge income disparities.

The proponents of NHI have this fanciful notion that everyone will have access to reasonable healthcare facilities. But the numbers suggest that people will be paying much more out-of-pocket. And that’s because if you take SA’s limited resources and stretch it out over the full population, everybody gets very little — if anything at all. This is because, just to take one constraint, there are not enough doctors to service the population as a whole.

We are who we are. We need more investment in healthcare, not less. And less investment is what the NHI will create because since it excludes the private sector, it will no longer have access to private capital.

It is so weird; this is precisely the moment when the government’s solution to its destruction of SA’s electricity provision and transport system is to draft in the public sector. Just when the state has demonstrated — and you can say this without fear of contradiction — its organisational, managerial and financial weaknesses, is the very moment it decides to take over the management of the healthcare system. It’s incredible. I wish I were making this up.

Gore is adamant that he, Discovery, and the private sector are not against NHI in principle. But they too are oblivious in two respects, IMHO. The first is that private sector healthcare has not managed to make its case outside of its bubble. The number of people covered by health insurance is not increasing and when you confront healthcare insurers about this problem, they tend to throw up their hands.

Gore’s response to this charge is that what SA needs is economic growth and more investment in healthcare. He says the industry is open to discussing, in depth with the government, how this should happen.

Gore makes the point that healthcare inflation is higher than general inflation because it’s the way the industry rolls: innovations don’t tend to reduce costs in healthcare, they tend to increase them (research, trials, patents, etc, make this so). I think he is right, but tell that to people with zero healthcare in SA right now. It’s hard.

So what is going to happen? Gore says, realistically, nothing will change for at least a decade. Then there will come a point (we don’t know when), where the health minister will outlaw private health insurance. And then we all throw away our healthcare cards and line up at Baragwanath with our lunch packs and our sheets, and wait for days to see doctors who are overstretched and nurses who are on strike.

Discovery, Profmed, and their ilk will only be able to offer “complementary cover for services not reimbursable by the Fund.” In other words, plastic surgery and stuff like that.

The bigger problem for me is that private healthcare has been trying to push the government on to a different path, which is not actually that different to the one they have chosen, by talking to its leaders.

I have seen industry after industry adopt what they think of as a “constructive approach” — the mining industry, the construction industry, and now the healthcare industry — using this “appeal to the logic of political leaders” notion. And they have all failed.

They have failed because fundamentally SA’s politicians don’t care about affordability, detailed finances or alternatives. What they care about is votes. And if it’s possible to frame a policy solution in a vote-catching way, it’s a done deal, finish and klaar.

The healthcare industry needs to convince not SA’s political leaders, but voters in general, that NHI is not a solution and that there are alternatives — but so far it has not come close. DM