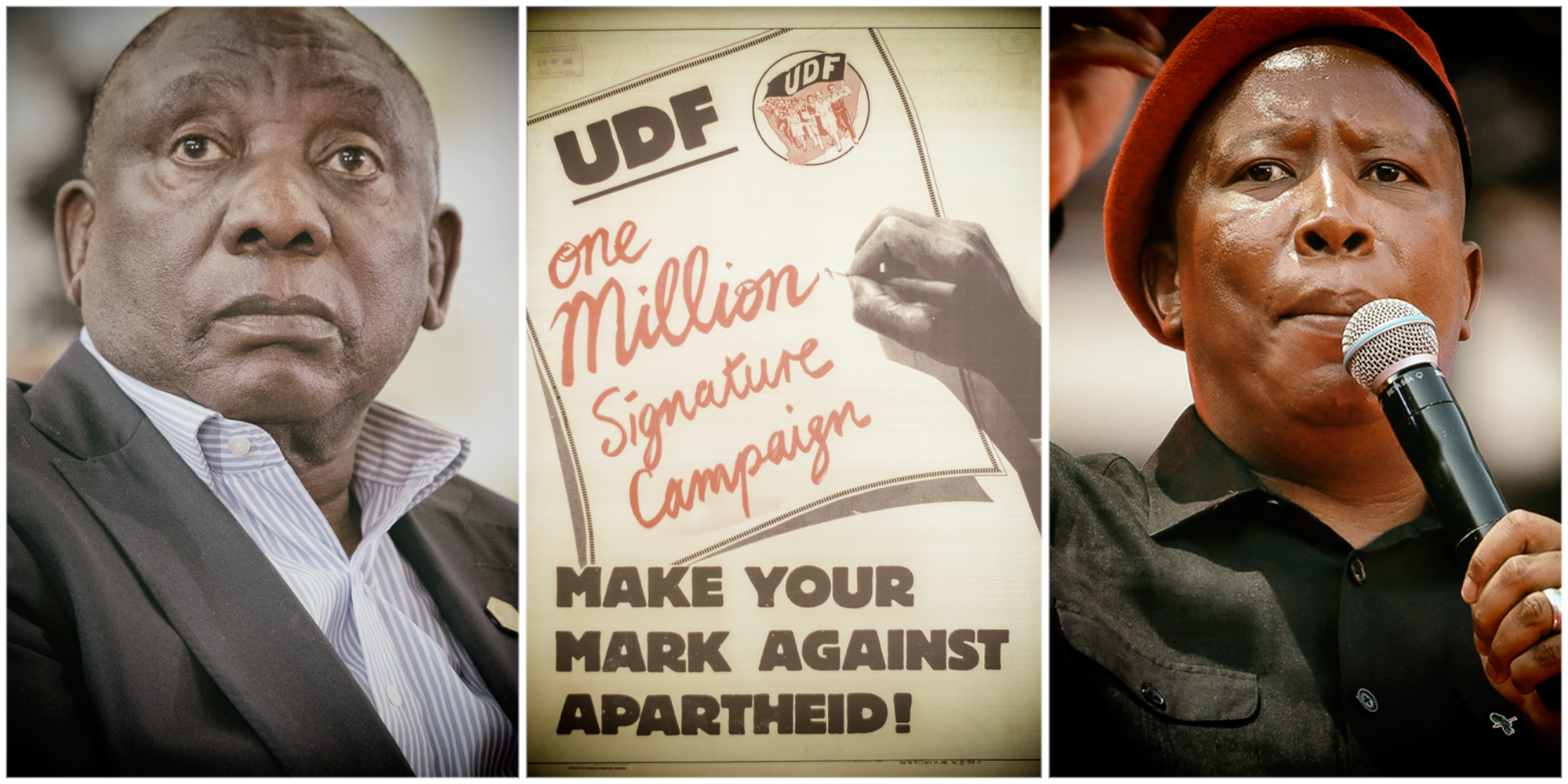

On Sunday, News24 reported that President Cyril Ramaphosa had told the 40th-anniversary commemoration of the United Democratic Front that Indian, coloured and white people “feel excluded” in South Africa’s political life.

As The Citizen put it, he also said that coloured and Indian people feel they are not properly represented in decision-making structures, and that “many white South Africans wrongly believe there is no place for them today, and some have drifted towards laager-style politics and a siege mentality”.

This comes amid a series of issues that have led to claims from these groups that they are suffering discrimination.

First, there were changes to regulations in the Employment Equity Act that allow the minister of labour and employment to set racial and gender targets for different industries in different areas.

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2023-05-30-employment-equity-act-yet-another-act-of-absurd-south-african-self-harm-looms/

Then there was a claim that the government was trying to limit the amount of water which can be used by farmers, under changes to the National Water Act. However, despite what was claimed, these changes apply only to what is described as “new water” — water that is being allocated to farmers for the first time. In short, farmers currently receiving water from our rivers will not be affected (it is worth noting that almost all of these farmers are white — it’s estimated that only 5% of agricultural water is used by “emerging” farmers).

Both these examples were useful for politicians looking to score points.

The ANC could claim that it was looking after its voters. But the DA and other parties could say they were opposing these policies in the interests of their voters (the DA referred to the Water Act suggestions as a Parched Earth policy).

More recently, EFF leader Julius Malema sang the song translated as “Kill the Boer” at the EFF’s 10th birthday rally, leading to the DA saying it would file charges at the United Nations for Malema’s “incitement of ethnic violence”.

This is a classic case of political parties deliberately dividing people for their own gain.

At the same time, the ANC has been aware of the feelings of coloured and Indian people for many years.

As far back as 2014, the then Gauteng Premier David Makhura said the government had “neglected coloured townships”.

A less diverse Cabinet

It certainly appears the top levels of both government and the ANC have become less diverse over time. A brief look at South Africa’s first democratic Cabinet under President Nelson Mandela and the current Cabinet will demonstrate this.

Also, some people feel that if they do not fit the demographic that the ANC or another political party is chasing, then the party ignores them — or worse, deliberately attacks them.

However, the true picture is more complicated than that.

As Professor Steven Friedman has observed, the voices of only around one-third of the adults in South Africa are heard in our national debate. Those in the middle classes have a louder voice than the poor.

And Indian, coloured and especially white people are surely more represented in these middle classes than black people.

It is also true that inequality has deepened since democracy. Those who were rich before 1994 and their children are more likely to be rich now than those who were poor.

That inequality has been to the benefit of some of the people within these classes (again, mainly white people).

At the same time, the proportion of white people in SA has declined to just 8.4%, while the proportion of coloured people is about 8.8% (based on the 2011 census, which has been published as a graph by Statistics South Africa; the 2022 census findings have not yet been released).

This would suggest that our current Cabinet is roughly representative of our population, although some groups are not represented.

This gets to one of the nubs of the issue.

In politics, symbolism is important, and if a group of people is absent from elected leadership, members of that group will notice. This is what gave the debates about the racial composition of our rugby and cricket teams such power 20 years ago. Much has since changed in those sports.

For example, it was surely politically significant, as Cyril Madlala noted, that no Indian people were elected, or even nominated, to the Provincial Executive Committee of the ANC in KwaZulu-Natal last year.

This trend has been evident in the ANC for many years and was first apparent in the ANC Youth League (ANCYL). From the time Malema took over leadership of the league in 2008, there was a noticeable absence of Indian, coloured and white people at ANCYL gatherings compared with the past.

It would be no surprise then, 15 years later, to find that there are also no Indian, coloured or white people in the ANC’s Top Seven national leadership.

The difference between this and the racial diversity of the all-male leaders of the new Multi-Party Charter for SA is striking.

There is yet another dynamic within all of this — groups that were accustomed to having power may feel its loss very deeply. But this does not mean they have less power than they should have.

That Ramaphosa made the comments that he did, as the President of South Africa and the leader of the ANC, is important.

But there does not appear to be any real motivation within the ANC to change the feeling of exclusion of white, coloured and Indian people. While it will occasionally campaign in the suburbs, it is likely to concentrate on townships, where most of its mainly black supporters live.

This will allow other parties to concentrate on Indian, coloured and white people, as they have in the recent past. It means that despite our daily reality, where in urban areas, schools and workplaces are becoming more diverse (despite huge problems, such as the recent example of the Crowthorne Christian Academy), political parties are still going to spend a large amount of focus devising campaigns that target racial elements of identity.

During this weekend’s UDF ceremonies, Ramaphosa noted that one of the organisation’s strengths was its slogan, “UDF Unites, Apartheid Divides”.

An apt description of South Africa’s modern moment may be, “Our Society Unites, Our Politics Divide”. DM