‘Where is the collective in this merry-go-round of miscommunication, missed opportunities, cumbersome licensing practices and blatant evasion? Buried under a thick layer of paper and data, the public interest that is supposedly at the heart of copyright never seemed more elusive.’ – Lion’s Share by University of Texas at Austin Professor of Ethnology and Anthropology Veit Erlmann

By almost any measure, the beginning of Sakhile Moleshe’s music career was an unqualified success.

Read more: Scratched Record Volume I

Plucked from his practice room deep in the bowels of the University of Cape Town’s music department in 2009, the young Eastern Cape jazz music graduate found himself in Ibiza, Spain, then Glastonbury, England, performing on some of the world’s biggest party stages as the featured vocalist for the multi-award-winning electro jazz duo, Goldfish.

Sakhile Moleshe, musician, composer and featured vocalist for the band Goldfish. (Photo: Sinethemba Konzaphi)

Sakhile Moleshe, musician, composer and featured vocalist for the band Goldfish. (Photo: Sinethemba Konzaphi)

Within a few years, Moleshe’s vocals on bangers like Fort Knox and Cruising Through were seemingly playing everywhere, racking up tens of millions of views and listens, and the group was sharing stages with massive acts, such as Faithless, David Guetta and a roster of international DJs.

Then came the single, We Come Together, a track co-written in 2010 by Moleshe and the Goldfish duo, David Poole and Dominic Peters, and released on the album Get Busy Living. The record won the Best Global Dance Album at the South African Music Awards the following year, along with several other nominations.

For the first time, Moleshe was listed as a composer on a Goldfish track, entitled to a portion of its ownership, and any royalties it would come to earn. Composer royalties are administered by the Southern African Music Rights Organisation (Samro), one of multiple Collective Management Organisations (CMOs) in South Africa that collect royalties on behalf of artists, record labels, publishers and songwriters.

As the song climbed the charts worldwide over the next months and years, Moleshe tried repeatedly to become a member of Samro, so he could claim his share. This required a simple application to be filled out and submitted. According to Samro, this core operating process “has been in place for many years” (the organisation was founded in the early 1960s), one that has evolved from a manual to an online system. In a response to emailed questions, Samro said the latest version requires “applicants to meet certain earnings thresholds to progress from Prospective to Associate to Full Membership”. Moleshe says he began applying as a first-year student in 2004, when physical forms were the available method.

“I promise you, I sat down and filled that form out about 40 times,” Moleshe told Daily Maverick.

No reply, no acknowledgement, no membership. Despite his demonstrated success and his growing repertoire, Moleshe says it took 15 years and a chance encounter at a dinner party in mid-2019 with the then Samro CEO, Nothando Migogo, to finally force the matter.

By August of that year, he had a battering ram with which to do so: his lawyer, the late Dr Graeme Gilfillan, had found out by searching on Samro’s self-service member portal that an International Performer Number (IPN) had been assigned to Moleshe’s name without his knowledge and royalties were being collected against it in at least 20 countries.

“I am unable to reap due benefit from this in any way,” Moleshe wrote to Samro general manager Karabo Senna on 28 August 2018. “I find it extremely disconcerting that I am unable to gain Samro composer membership, yet my name is in the [International Standard Musical Work Code] database.”

Moleshe became a member shortly thereafter, and he was paid out a small lump sum. But then Samro came back with bad news: because he had taken so long to claim his royalties on songs he’d written throughout the early 2010s, his share of We Come Together and other compositions had actually been prescribed, or “written back”.

This means that unbeknown to him, Moleshe had had just five years from the date of registration of each track – subsequently revised down to three years – to identify and claim his royalties. When he failed to do so, they were declared “unclaimed” and prescribed. Left unclaimed, because he had been unable to become a member until 2019, Moleshe’s royalties were incorporated into “undoc”.

In industry parlance undoc – short for undocumented works – is a murky slush fund of royalty payments owed to the composers and publishers of songs both local and global for which, according to Samro, the “rights holders are not known [or] have not yet been documented” – or, in Moleshe’s case, haven’t claimed their royalties in time.

Declaring works as “undoc” and saving the royalties in bank accounts at interest rates undeclared to members in annual financial statements is a common practice in the South African music industry, and one often at the root of frequent complaints about its collusive and corrupt practices.

Every CMO and record label reportedly has an “undoc” slush fund, tempting abuse of this opaque resource, which can accrue to hundreds of millions of rands, according to Gilfillan, who was a copyright specialist as well as a lawyer, and a controversial figure for the bombastic tone of his frequent industry criticisms.

During apartheid, “undoc” was called “the Black Box” – a term which was eventually deemed inappropriate both for its racial undertones (at a time when black musicians were almost never paid their due) and for its sinister implications.

Sakhile Moleshe during Cassper Nyovest vs Priddy Ugly celeb boxing match at SunBet Arena in Pretoria on 1 October 2022. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)

Sakhile Moleshe during Cassper Nyovest vs Priddy Ugly celeb boxing match at SunBet Arena in Pretoria on 1 October 2022. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oupa Bopape)

After Samro explained to Moleshe that his royalties had been written back (even though the Prescription Act of 1969 states that prescription is “interrupted” if the beneficiary is unaware of or unable to claim his royalties), it dropped a second bombshell: it would now be deducting the lump sum payment it had made to him from his future royalties, recouping them over time. By early 2022, according to Samro correspondence, the “current outstanding debt to the payment on account” was still sitting at R7,727.86.

What’s more, Samro would claim an average of 30% from those royalties for “administration expenses” over the next few years, according to its annual financial statements – a figure three times higher than the roughly 10% average fee deducted elsewhere in the world.

Examining this last fact more closely, Samro’s financial statements show total costs as a percentage of revenue distributed between 2019 and 2022 as averaging 44%, verging on half a composer or publisher’s allocation, a figure far higher than the global average.

(Samro told Daily Maverick the “regulatory landscape for CMOs is very different in European countries from that in African countries, and as such, their revenue base cannot be compared to Samro”.)

“I feel sorry for the average young rapper with no business savvy, because … artists get taken for a ride in this country almost every damn day,” Moleshe wrote in a frustrated Facebook post in May 2020. By then, he was a solo artist releasing his debut album, with very different earning potential to his days in an established, globally renowned band. “Legal advice says [Samro’s actions are] bullshit of course,” he wrote. “But … I can’t afford to fight it.”

Dozens of musicians sympathised in the comments. It was a bitter – and very likely unlawful – pill to swallow: Moleshe had finally become a Samro member and could collect the royalties due to him, only to be told Samro would be recouping those historical royalties, and spiriting them away into its slush fund to accrue interest for someone else’s benefit.

Due to no fault of his own, Moleshe had become one of thousands of South African musicians not being fairly or sufficiently compensated for his considerable talents and success.

A study released in 2023 by music researcher Gwen Ansell found that, of the 711 recipients of the Jazz Income Relief Fund administered by Pro Helvetia in South Africa during the Covid pandemic, veteran musicians with “substantial professional experience” reported earning only around R26,000 a month, “no more than a mid-level, formally employed technical worker”.

“[Samro] is crooked,” Moleshe alleged to Daily Maverick. “The whole system is.”

(Samro told Daily Maverick it could find “no evidence” to support Moleshe’s claims – the organisation says it could find no record of his attempts to register before 2018.)

Between 2011 and 2022, according to an independent analysis of Samro’s annual audited financial statements, the amount of royalties that were officially “written back”, as in Moleshe’s case, amounted to a staggering R466.3-million. (Samro claims it paid out “significant royalties” to members during that time, totalling a similar amount: R471-million. It did not specify how this was possible, but placed the burden on composers and publishers to try to identify any missing royalties within its system. It told Daily Maverick that it provides members with “a process that allows them to claim royalties for undocumented works by providing [Samro with] the necessary documentation and evidence within three years of the allocation.”)

“It’s an old trick in the music industry: ‘If you don’t ask for your money, we won’t pay it to you’,” former recording producer and industry veteran Clive Hardwick said. “It goes into the ‘black box’. If you don’t ask for it, how do we know who to pay?”

Aemro unresolved

Two of the most notable “undoc” write-back figures (R51.8-million and R60.2-million) in Samro’s recent audited financials appear to have been ploughed back into the organisation’s bottom line in 2017 and 2018, right as the organisation was reeling from a major scandal. It remains unresolved and uninvestigated by South African law enforcement.

About R47-million had been lost to “unjustified enrichment, fruitless and wasteful expenditure” on establishing a new subsidiary CMO in Dubai, called Aemro. This caused “serious financial prejudice” to Samro, according to the second of two forensic reports commissioned (the first by PwC in 2017; the second by SekelaXabiso in 2018).

The subsidiary’s stated aim was to “set up a collecting society with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) government being the local partner and shareholder”, to administer the use of music in the region and increase profits for Samro’s — and other global CMOs’ — members, according to board meeting minutes from 26 June 2014.

Aemro would’ve been the first of its kind in the region at the time – the 110-year-old British CMO Performers Rights' Society had tried and failed to establish a branch in the UAE, which should perhaps have given Samro’s board and executives pause. (In 2020, a CMO called the ESMAA was finally established in Abu Dhabi to represent the rights of music creators in the Gulf. More organisations have subsequently been established.)

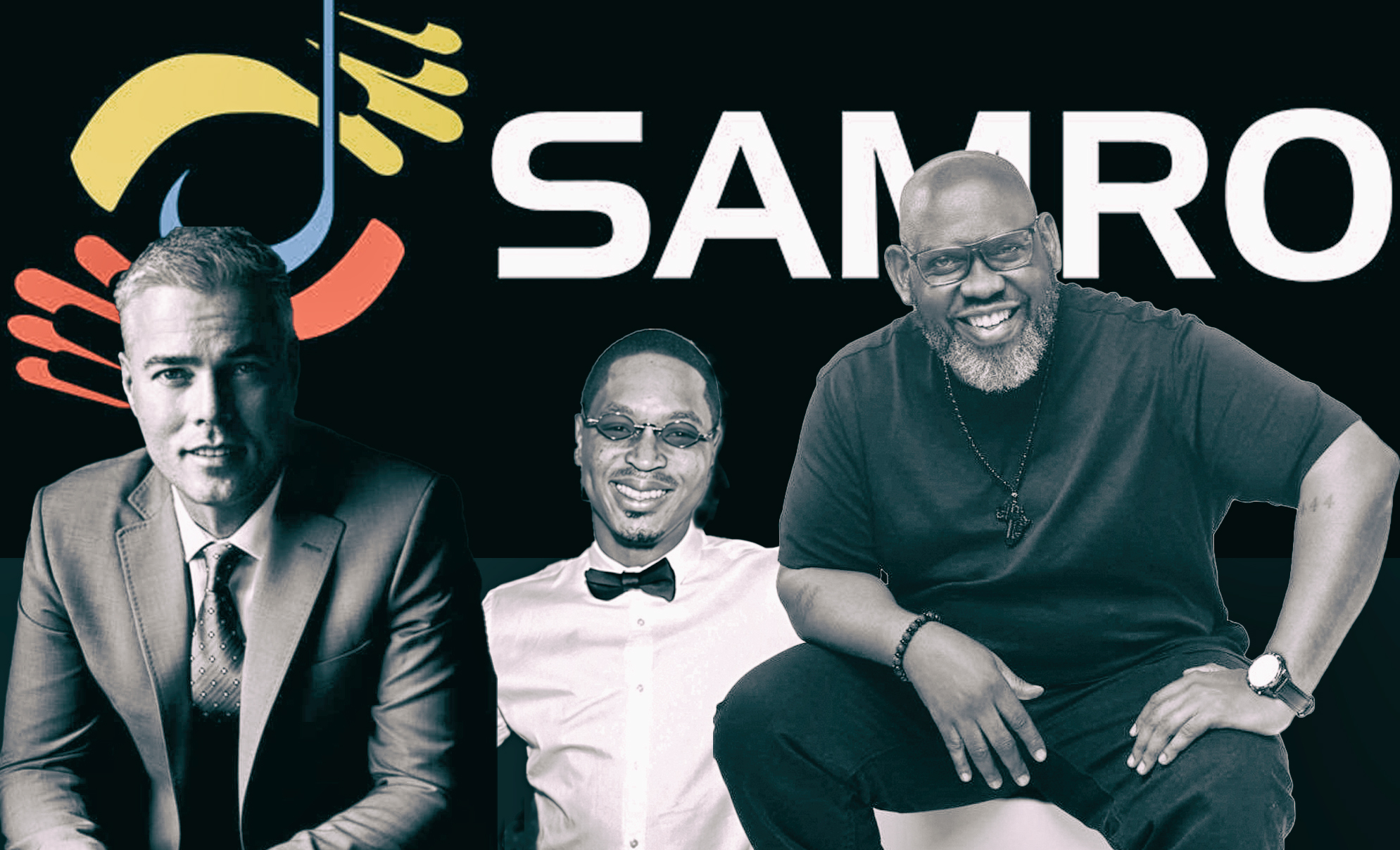

Sipho Dlamini, former CEO of Samro and Universal Music Group. (Photo: Facebook)

Sipho Dlamini, former CEO of Samro and Universal Music Group. (Photo: Facebook)

A young businessman called Sipho Dlamini had been promoted to CEO of Samro in June 2013. After a stint working in Dubai, he moved to South Africa and dashed up the organisation’s ranks, from GM of marketing in 2012 to head of the organisation the following year. In August 2013, the board of directors authorised him to “sign all documents and do all things necessary” to further Samro’s aims, “indemnified [from] any liabilities” in the course of his work, according to a 1 August round robin resolution seen by Daily Maverick. In other words, he was given free rein to set up the new entity. But minutes from subsequent meetings show the board and the executive were involved in and aware of the decisions that led to Aemro’s expensive establishment and its rapid demise, in 2017.

“There was continuous supervision and oversight regarding this project during my tenure at Samro”, Dlamini told Daily Maverick in a detailed response to emailed questions. “The Board’s involvement in the Aemro project was extensive and began as early as 2013, [before my tenure],” he wrote. “This hands-on approach continued up until the successful registration of Aemro, in October 2015.”

After hiring local lawyers Nseir and Omar Jaber of Advolaw to set up the paperwork – and granting them power of attorney over Aemro – Dlamini and Samro hired Hamza Khalaf, a Syrian national and former colleague of Dlamini’s from a conceptual design company in Dubai called Creative Kingdom. They also hired Khalaf’s relative, Yaser Aljabal, who was “a seasoned IP protection executive with experience working with the Dubai and Abu Dhabi governments, as well as global brands,” according to Dlamini.

According to documents in Daily Maverick’s possession, Khalaf and Aljabal owned a company called IPR Management, and they presented a business plan to Samro’s board in Johannesburg in March 2015. Aemro was registered by October, with offices in Dubai Media City, and the two consultants were put on a sizeable retainer of roughly R518,000 each a month. IPR Management became a 20% shareholder in Aemro, entitled to 5% of the organisation’s administration fee, which would escalate with increased revenue.

The first of the two forensic reports later found that the South African Reserve Bank had denied Samro’s request, as a non-profit company, to invest in a foreign entity. It was compelled to establish a new entity in the UAE, Music Rights House FZ-LLC, but by the time the first report was published in August 2017, the investigators had not been provided with “any documentation as to whether [Samro’s] shareholding in Aemro was transferred to Music Rights FZ-LLC”.

By mid-2017, Aemro’s operations were still in limbo, waiting for clarity on the required membership approval of the global body, Cisac. Aemro did not yet have reciprocal agreements with other global CMOs that would give it a mandate to collect royalties in the UAE on behalf of artists everywhere, although Dlamini told Daily Maverick that the intention to register Aemro had been announced at a Cisac General Assembly in June 2015, and representatives from member organisations had conveyed support for the initiative.

More importantly, according to both forensic reports and Samro board minutes, by June 2017 Aemro did not yet have a vital federal operating licence from Dubai’s Ministry of Economy, despite IPR Management’s much touted government relationships. By then, roughly R37-million in South African composers’ and publishers’ royalties had already been spent on the CMO’s establishment.

At a Cisac meeting in April 2017, the organisation said proof had not yet been provided to demonstrate that Aemro had or was in the process of applying for a federal licence. (Dlamini told Daily Maverick Aemro had received the “establishment card issued by the Ministry of the Interior” before he resigned, along with the required Dubai trade licences.)

In March 2016, Dlamini left Samro to take up the position of CEO for sub-Saharan Africa of Universal Music Group, a role he also quietly resigned from with immediate effect in March 2023.

More than 10 people who worked with or knew Dlamini during his tenure spoke to Daily Maverick under the condition of strict confidentiality, for fear of reprisals, about lavish spending of company resources, a culture of toxic masculinity and abuse of power. (“You will no doubt appreciate that in circumstances such as this, those providing such information may have a grudge against me for whatsoever reason as well as an alternative agenda [sic],” Dlamini wrote to Daily Maverick in response to these allegations.)

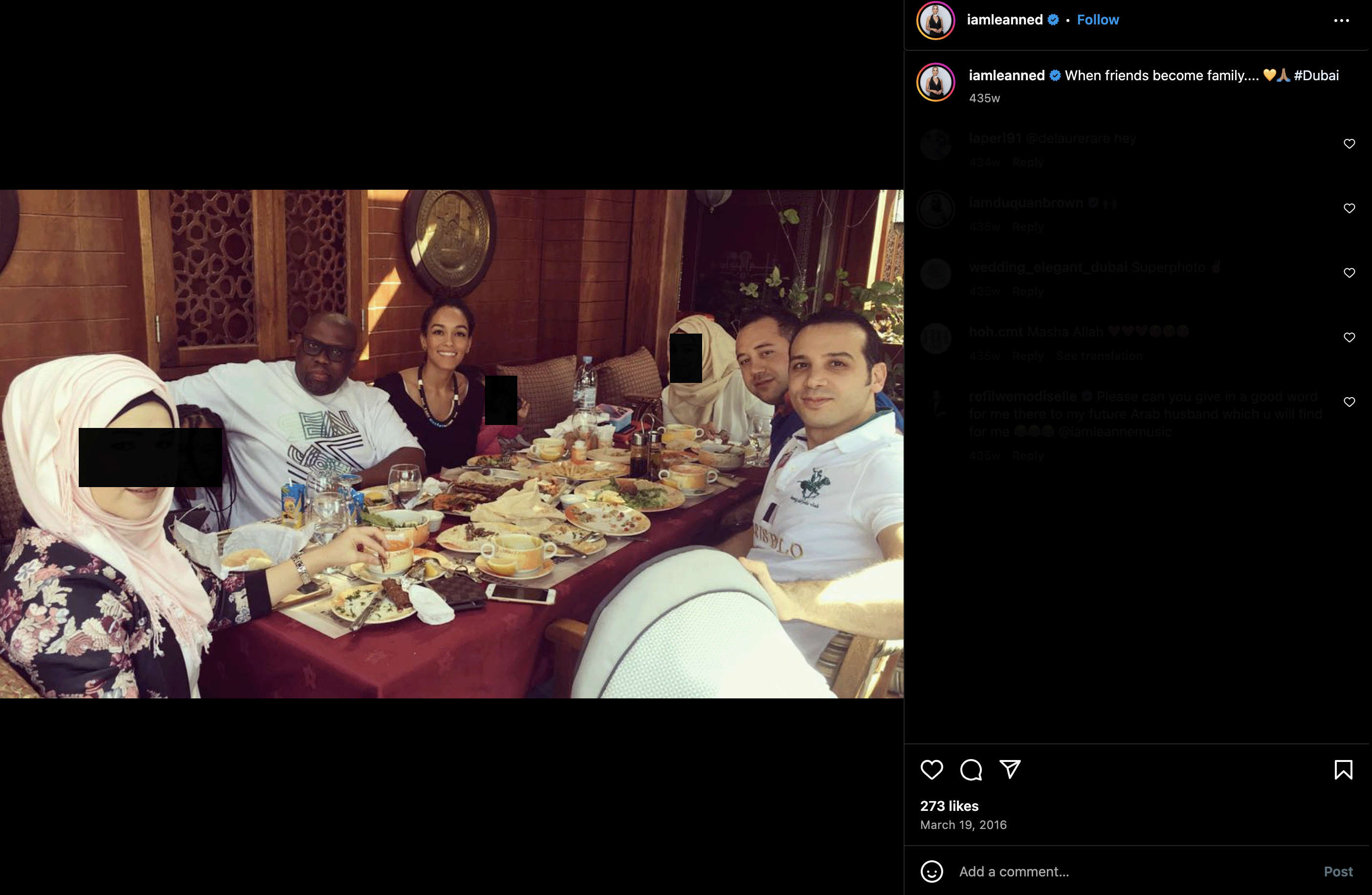

During his two and three-quarter years as CEO at Samro, a non-profit company, content posted on social media by Dlamini and his wife, singer and influencer Leanne Kistan Dlamini, shows the couple took at least seven international trips, mostly to Dubai, first class, sometimes with their whole family. Dlamini denies that Samro ever paid for his family members.

The Dlaminis with Hamza Khalaf and Yaser Aljabal in Dubai on 19 March 2013, shortly before Sipho Dlamini became CEO for sub-Saharan Africa of Universal Music Group. (Photo: Instagram)

The Dlaminis with Hamza Khalaf and Yaser Aljabal in Dubai on 19 March 2013, shortly before Sipho Dlamini became CEO for sub-Saharan Africa of Universal Music Group. (Photo: Instagram)

Despite R18-million in wasteful expenditure on Aemro by the end of that year, when he resigned in early 2016, Dlamini was reportedly paid a leaving bonus of at least R500,000 (not included in his employment contract), and given a vehicle worth R240,000, according to documents in Daily Maverick’s possession. Dlamini told Daily Maverick bonus payments are “always at the discretion of the board, based on the performance of the company,” and that the vehicle was part of “a standard process that provides employees an option to buy the company car they have used during employment”.

Documents state Dlamini was released from reimbursing a pro-rata restraint-of-trade payment for early termination of his employment contract, paid to him when he became CEO. He was also offered a consulting contract by the interim CEO who replaced him, board member Reverend Abe Sibiya. This was reportedly granted without the board’s approval and was worth R235,600 a month for four months. (Dlamini disputes this, writing: “Samro requested my consulting services to ensure continuity. This was part of the agreement reached between me and Samro relating to my departure and the provisions in my contract of employment.”)

Screengrabs of Dlamini family trips.

Screengrabs of Dlamini family trips.

The second forensic report on Aemro found there was “prima facie justification to claim certain amounts back from Mr Dlamini and possibly Messrs Khalaf and Aljabal for gross dereliction of duty and … unjustified enrichment”.

It also found that the board “failed in its oversight and fiduciary responsibilities to actively monitor this operation”. In 2018, Dlamini told the media Samro was using the SekelaXabiso forensic investigation as a “scapegoat strategy” against him — a position he maintains, telling Daily Maverick that the findings against him are “false and defamatory”. He went on to say that “further publication of those findings would constitute a separate unlawful and defamatory publication about me unless my version of what happened and these responses are dealt with adequately [sic]”. He declined to share any documents supporting “his version of what happened” on the record, however.

Dlamini is still working in the music industry: he is the Africa & Middle East president at gamma, a “modern media and technology enterprise”, with an office in Dubai.

***

A further R29-million was spent on Aemro and IPR Management in 2017 and 2018, before the board elected to dissolve the project. Overall, IPR Management would eventually bill Samro a total of R31,772,602.93 between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2017.

At least 86% of payments from Samro to cover office rent, parking, salaries and other administrative expenses went straight to IPR Management and not to Aemro’s Dubai bank accounts, according to the PwC forensic report. Khalaf and Aljabal were paid settlement amounts totalling roughly R7-million, to break their employment contracts early.

Despite the recommendations of the forensic reports to pursue the case further, Samro told Daily Maverick in an emailed response that it had “followed due process, the matter was reported to the relevant authorities who, upon reviewing the evidence, made a decision not to prosecute”.

Written-back royalties in the organisation’s “undoc” slush fund kept it afloat, according to its financial records, despite at least two years of technical insolvency.

Mark Rosin, a prominent media lawyer who was brought in for a short stint as interim CEO several years after the fact in 2020 to help “turn Samro around”, said that, in the absence of fresh information or evidence following the publication of the forensic reports, the organisation chose not to continue to investigate Dlamini, Khalaf, Aljabal and Aemro.

“There were many things that needed to be fixed in the business if I wanted to turn it around,” Rosin said. “So it was like, well, I’ve only got eight to 10 hours in a working day and even if I’m working seven days a week, if I’m going to try to do everything to try to fix Samro and try to unravel and get to the bottom of Dubai, I’m going to fail on both scores. I’ve got to focus on the future.”

Rosin is credited with, among other things, opening access to Samro’s undocumented works catalogue in an effort to help composers identify unclaimed royalties before prescription.

But for members and critics, the Aemro scandal remains an open wound, one which is indicative of a broader culture of impunity and exploitation at the hands of executives within the music industry at large.

In a more recent but far less publicised scandal, Samro informed members on its website in December 2023 that another forensic report, commissioned by the board last year and verified by an independent third party, had confirmed fraud within its system after finding that members had been claiming royalties that did not belong to them. The investigation highlighted “weaknesses in internal controls”, Samro said at the time, adding that the case had “been handed over for investigation to the South African Police Service”, once again placing the onus on the beleaguered law enforcement system to pursue justice for Samro members.

In an emailed response, Samro told Daily Maverick that “a process is currently underway, which has been communicated to the affected parties including Samro Members [sic]”. But it would not provide the report, in order “not to prejudice those involved”.

Correspondence sent to Hamza Khalaf requesting comment on the findings of the Aemro forensic reports went unanswered.

Administering rights, wrong

Samro is one of South Africa’s oldest institutions. Established in 1961, it is the largest CMO on the continent, responsible for collecting royalties for public performances, broadcasts and diffusion services. It has more than 18,000 members – all of them music composers, authors and publishers – who rely on Samro to issue blanket licences to television and radio stations; clubs; bars; restaurants; events venues and retailers — roughly 15,000 licensees in total. It then administers the income and pays members their royalties, according to how often their songs get played.

The model sounds simple enough – receive the licence money; administer it; pay out the royalties. But in reality, the job of protecting copyright and administering royalties in a previously segregated and isolated country – one that is now a part of a deeply integrated and completely digitised, global economy – is anything but straightforward.

In addition to its local members, Samro collects royalties for composers and publishers in other countries, represented by their own CMOs, and receives royalties in return. The “currency” of Samro – the compositions – can include dozens, sometimes hundreds, of people: The composer, lyricist or songwriter, singer, session musicians, producer and recording technicians all have a hand and a voice in the final assembly of sound. All are entitled to fair representation and compensation.

As a result, there are multiple CMOs in South Africa. Some collect for the performers of songs. Some for the writers and publishers. Some represent the biggest interests in the industry – the record labels. And some representing the little guys – the independents. Samro is by far the largest such organisation, with an annual revenue of R600-million in the 2023 financial year.

Often, however, the system just doesn’t seem fair.

Renowned musician and record producer Sello Chicco Twala and members of a new representative body called the Pay Our Royalties Movement (Porm) have accused the multinational record label-controlled industry and the CMOs that administer the music economy on its behalf of behaving like an organised criminal syndicate that is hindering the sector’s growth.

Attempts to engage with the major record labels on the matter of royalties – and to lobby for more say for musicians in the running of the music economy – have failed. When Porm gathered at the Zone in Rosebank on 30 April to deliver a memorandum to the MD of Universal Music Group, Manusha Sarawan, staff simply locked up and fled the building.

But technological advancements in music monitoring, along with a David vs Goliath-style legal case – the focus of the second part of this investigation, coming soon – brought by former independent music producer Clive Hardwick, are creating conditions for musicians to demand a better, fairer and more transparent system.

They should start, say industry veterans, by withdrawing their membership en masse to the country’s main CMOs – Samro; the South African Music Performance Rights Association (Sampra); the Composers, Authors and Publishers Association (Capasso) and the Recording Industry of South Africa’s audio-visual association, RAV – to protest against a system that, in too many cases, over too many years, has failed in its primary function: paying musicians for their music.

“Samro is a template for all the CMOs, because it’s by far the oldest one, and because they all collect their revenue from the same place,” Hardwick said.

“In the digital age, it should be easy and inexpensive to administer [royalties] and get it right, but there’s no incentive to do that, because the people who are running the show are benefiting,” Hardwick said.

A system for the people, against the people

Over the course of Moleshe’s career, South Africa’s contribution to global recorded music revenues has shrunk to a figure very close to zero, even as international figures have soared in the opposite direction. In its annual Global Music Report, published in April, the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) announced that global revenues for recorded music reached $28.6-billion in 2023, off the back of a seven-year, streaming-led growth cycle. One of the most quoted clickbait headlines from the report touted South Africa’s “world-leading” revenue growth rate of 20%, driving sub-Saharan Africa into first place at 24.7% cumulative growth.

Yet what the glossy document and misleading headlines failed to mention is that South Africa’s total revenues for recorded music consumed in South Africa, according to the Recording Industry of South Africa (RiSA), totalled R878,813,905.62, or roughly $47.7-million last year – less than 0.18% of the global revenue figure. Revenue generated bySouth African music in 2023 amounted to an even more minuscule sum – just R167,880,898.15, or $9.1-million.

In other words, South African-recorded music’s “record-breaking” 20% growth rate generated less than $10-million globally in 2023. Of that paltry sum, the overwhelming bulk went directly to the three largest record labels – the “majors” – Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment and Warner Music Group, headquartered overseas in the United States and Europe. Their share of the South African market totals more than 80%.

While South African musicians’ net worth dwindles ever nearer zero, globally, music has never been more valuable. As the Financial Times wrote in September 2022: “In recent years, music streaming has resuscitated industry revenue, while central banks cut interest rates to historic lows, sending investors searching for new sources of returns. The result: the world’s biggest investors poured billions into what had been a staid sector and music royalty payments were turned into a recognised asset class.”

In 2023, Universal HQ’s revenue hit its highest number yet – €11.1-billion. Sony earned $10.35-billion, Warner $6.03-billion. That heady success is not reflected in the South African music sector.

Executives from the majors – including Sony Music Entertainment MD Sean Watson, who was a central figure in a R65-million wasteful expenditure of public funds scandal in 2014 investigated by Daily Maverick last year – sit on the boards of both RiSA and Sampra.

Sean Watson, the MD for Africa of Sony Music Entertainment. (Image courtesy of Facebook)

Sean Watson, the MD for Africa of Sony Music Entertainment. (Image courtesy of Facebook)

David du Plessis, who was the COO of RiSA between 2002 and 2015, and the CEO of Sampra until 2016, said he left the latter organisation in protest when it became clear to him that he would be expected to rubber stamp practices between the two organisations and certain members of their boards that were not in adherence with the principles of good corporate governance.

This included the sponsorship of the category Sampra Best Artist of the Year, at the 2016 South African Music Awards, administered by RiSA under its CEO, Nhlanhla Sibisi. The sponsorship amount was inexplicably inflated from R12,000 the year before, to R600,000 (excluding VAT), after the awards event had taken place.

“As the CEO of Sampra, the first time I got to know about the increased sponsorship amount was when I received RiSA’s invoice, one month after the event,” Du Plessis said. The amount was not budgeted, and could otherwise have been paid to performers and record companies.

The Black Box

Sadly, Sampra and Samro echo each other, highlighting the issue with CMOs more generally. As in his experience with Samro, Moleshe says he also had a similarly difficult time of signing up with Sampra. He was eventually introduced to an administrator by his Goldfish bandmates, and became a member in 2019.

Where Samro administers royalties on behalf of the composers, lyricists and publishers of music, Sampra administers on behalf of artists who perform that music and the record labels that represent them. This is known in the industry as “needletime” – from the days when radio stations publicly broadcasted a certain portion of a track on a vinyl record from a gramophone, sometimes referred to as “pay to play”.

Sampra began administering needletime royalties in 2007, during a protracted and complicated 15-year legal battle to get broadcasters to pay performers fairly. It was helmed in large part by industry veteran Keith Lister and helped formalise the royalties system. However, it left licence holders – broadcasters, streamers and retail outlets that play music – having to pay two separate amounts for their playlists every year: one to Samro, one to Sampra. Naturally, this created resentment and confusion. Two licences — and two payments — for the same music?

Things grew more complicated. An organisation called Capasso was established in 2014 to continue the work of collecting mechanical – streaming and digital – royalties on behalf of composers and publishers. RiSA established RAV back in 2000 to collect music video and audio dubbing royalties.

In an open and largely unregulated market, both local and global independent CMOs also sprang up over the years, as the profit motive of playing middlemen to musicians — who are frequently denigrated as being “unable” or “uninterested” in tending to the business administration side of their craft – became more craven.

One of the biggest questions surrounding CMOs remains the so-called “undoc” issue — the slush funds of royalties disconnected from their rights holders that Moleshe’s allocation disappeared into at Samro. This has troubling global implications as well. Because a large majority of the music played on South African airwaves belongs to international, predominantly American, artists, the share of royalties owed to non-South African artists and composers is concomitantly high.

However, Sampra does not have what’s known as “reciprocal agreements” with CMOs in America to collect needletime (performance) rights. That has not stopped it from implying it is paying American artists their due royalties in its annual reviews. An independent organisation founded by Twala and Du Plessis, called Imbokodo Collecting Society, last week signed a reciprocal agreement with a new CMO in the United States, Universal Royalty Exchange - the first of its kind between the two countries. The partnership pledges to “address past issues of undistributed royalties and introduce new benefits for American and South African performers ... to ensure accuracy and transparency in the collection process”.

On its website, Sampra appears to have deliberately tried to obscure the fact that it does not have reciprocal rights with CMOs in the United States. The screengrab below shows how, on a pin on the state of Georgia, the hyperlink that pops up takes the user to the website of the Georgian Copyright Association, a CMO in the country of Georgia, in Eastern Europe.

Sampra has no relationships with CMOs in the United States because that country does not recognise needletime rights. It is believed that a huge amount of American artists’ royalties are sitting in the “undoc” slush funds at Sampra, RiSA and the three majors, accruing undeclared interest, or being utilised for undeclared activities.

“There’s no transparency in the industry, so we don’t know what is being distributed, why or to whom, and we’re not sure exactly how much is in each of those ‘black boxes’,” Hardwick said.

Following an independent analysis of Sampra’s 2023 audited financial statements to try to better understand some of these issues, Daily Maverick sent Sampra CEO Pfanani Lishivha an email in September 2023, and again in November, asking for clarification on more than 30 aspects of the report.

Emailed questions sent to the organisation’s PR and marketing officer, Yvette Rammalo, on August 21, went unanswered. Daily Maverick has also been in contact with RiSA on numerous occasions for comment on these and other matters. No replies have been forthcoming.

As long as these opaque practices continue, musicians will continue to be starved out of the industry. If South Africa hopes to keep fostering talent and listening to beautiful music, something must change. DM

So what is happening to the royalties of artists and composers in South Africa? And why is it so difficult to obtain information about these and other questions about how royalties are administered? Part Two of this story, An Embarrassment of Royalties, will be published in the coming days.

Sean Watson, the MD for Africa of Sony Music Entertainment. (Image courtesy of Facebook)

Sean Watson, the MD for Africa of Sony Music Entertainment. (Image courtesy of Facebook)