By the standards of our time, Charles Bell was a polymath: anything he turned his hand to he succeeded in accomplishing. In this, he was the perfect product of the 19th century: a time of inventiveness and creativity in which no endeavour was deemed to be impossible.

Even among skilled Victorians, however, he was extraordinary. Born in 1813 and a product of St Andrews University in Scotland, his insatiable inquisitiveness led him first to cartooning and art, then exploration, land surveying, cartography, lithography, photography, meteorology, archaeology, palaeontology, philately, heraldry and numismatics (the study of coins and medals).

He designed stamps (including the famous Cape Triangular), medals, silverware, banknotes, carved wooden plaques, heraldry, book covers, stained-glass windows. He illuminated books, made ceremonial trowels and spades, engraved wood and brass, collected traditional Scottish ballads and Celtic harps. He even invented a tarred sailing catamaran — which nearly cost him his life when it capsized off Sea Point.

When Bell was but 20 years old, the Cape’s surveyor-general, Sir Thomas Maclear, predicted that he would make a success of simply anything he undertook.

Portrait of Charles Bell. Image: WikiCommons

Portrait of Charles Bell. Image: WikiCommons

His contacts were, to say the least, interesting. As a young man, he dined with Charles Darwin during the latter’s stopover at the Cape on his voyage aboard the HMS Beagle. He was a close friend of, among others, the renowned astronomer Sir John Herschel (who described Bell as a man “with extraordinary talents”), Scotland’s eccentric astronomer-royal Charles Piazzi Smyth, the roadbuilder Andrew Geddes Bain, crusading journalist John Fairbairn, the artists Thomas Baines and Thomas Bowler and the missionary Robert Moffat. He even had a favourable audience with Basotho King Moshoeshoe and Matabele Chief Mzilikazi.

At a time when colonial expansion was riding roughshod over the rights of indigenous tribes, he deplored the manner people were being deprived of territory traditionally. He recommended a just re-allocation similar to that being undertaken by the present-day land claims court. He was director of Old Mutual and the municipality of Bellville was named after him.

Throughout his life, he retained a sense of fun and an awareness of the grotesque and the comic that sparkled through his works.

But history is selective about those it canonises and, after his death in Edinburgh in 1882, the memory of his extraordinary achievements soon dipped out of popular memory.

There are several reasons for this.

Bell’s early sketches of an expedition to the Tropic of Capricorn were to have been published, together with an account of the journey, by expedition leader Dr Andrew Smith. The book, however, never appeared.

Much of Bell’s carvings and stained glass work was destroyed when his beloved house, Canigou, in Rondebosch, was burnt to the ground. Two-thirds of a collection of his documents were somehow ‘lost’ and fine pieces of his work mysteriously disappeared. He seldom, if ever, sold his works — he gave away many — so his art tended to remain with family or friends rather than in galleries. Much was lost or collections were broken up, over the years.

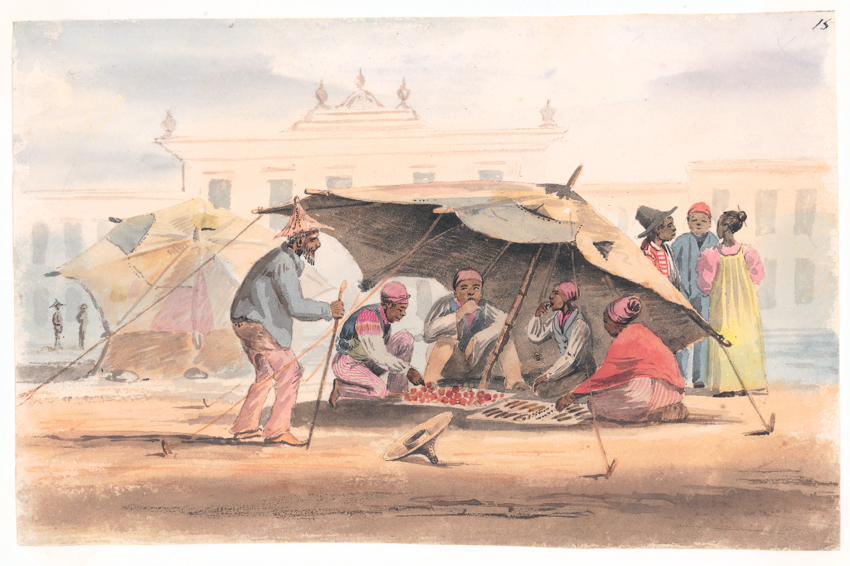

Malay traders in Cape Town. Image: WikiCommons

Malay traders in Cape Town. Image: WikiCommons

An early acquaintance of the artist, Sir Charles D’Oyly, got Bell reaching for his pencil and sketchbook and he was soon capturing the life around him with a critical and comic eye.

Undoubtedly influenced by the satirical cartoonist George Cruikshank, he often depicted people he saw in unflattering caricature.

He soon progressed to pen and ink and, in a way no other Victorian artist had done, captured the life of both rich and poor in the scruffy little town below Table Mountain.

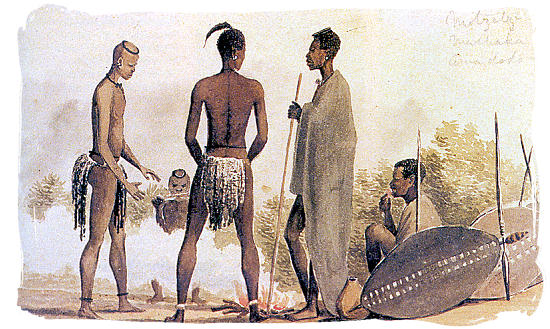

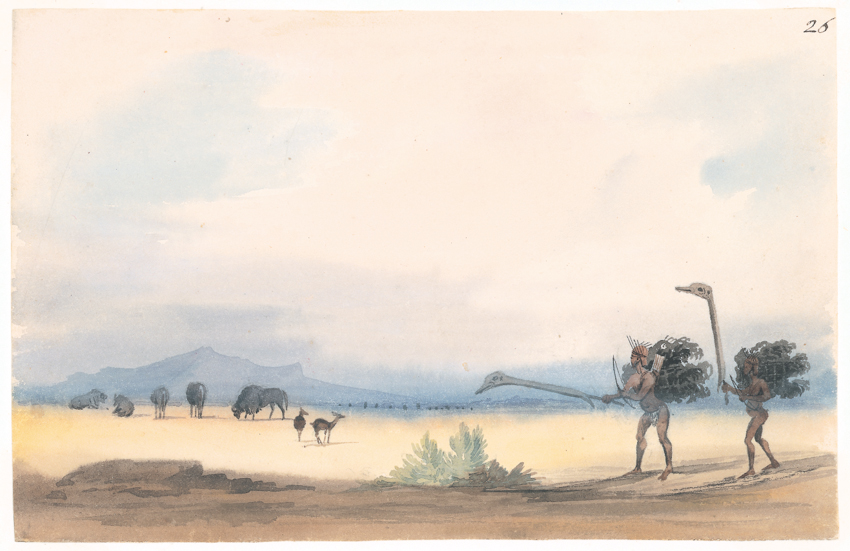

His skill got him chosen as the artist for a two-year expedition with Andrew Geddes Bain into the wild interior — through Kuruman and past the Magaliesberg Mountains to the Tropic of Capricorn. His sketches of Africa and its peoples set Cape Town abuzz with excitement after his return.

Bell’s work as a humble civil servant after this adventure seems to have been simply a platform from which to sketch and to tramp the social round of dinner parties and society balls. But he clearly yearned for a challenge and, at the age of 24, he sat the appropriate examinations and qualified as a land surveyor. It was a profession that was to occupy Bell for the rest of his working life.

Work by Charles Bell. Image: SWikiCommons

Work by Charles Bell. Image: SWikiCommons

Surveying allowed him to travel — and travel he did, even dragging his new wife Louisa, then pregnant, all the way to Grahamstown in an ox-drawn wagon.

In 1847, Bell and his family sailed for England to holiday with his parents. It was to be a fateful visit.

On the return trip, Louisa, then three months pregnant with their third child, caught the eye of an army surgeon named Lestock Stewart. Back in Cape Town, Louisa and Stewart were seen entwined on the campground in broad daylight and, soon afterwards, Bell arrived home early and “found the guilty pair.” The divorce was a messy affair and became the talk of Cape Town.

A decade later Charles Bell was to marry Helena Krynauw, 26 years his junior. It turned out to be the perfect match.

The arrival of Van Riebeeck by Charles Bell. Image: WikiCommons

The arrival of Van Riebeeck by Charles Bell. Image: WikiCommons

Painting by Charles Bell. Image: WikiCommons

Painting by Charles Bell. Image: WikiCommons

By the 1860s, Bell was a pillar of Cape society and director of Old Mutual. But his work as surveyor general and his almost feverish artistic endeavours were beginning to take their toll. He suffered blinding headaches and his eyesight was playing up. He took a brief holiday in Britain but, on his return, the problems continued. In 1871, he resigned and, the following year, he and Helena sailed with their children for England.

Exactly 10 years later — during which Charles never stopped being creative — Helena died at the early age of 42. Charles was grief-stricken. His headaches proved intolerable and the eyesight in his better eye failed. Six months after Helen was buried, he died.

Shortly afterwards Scotland’s Astronomer Royal, Charles Piazzi Smyth, wrote to the Royal Society informing it that Bell was “such an artist as showed him to possess the soul of a true genius, if there be anyone in the world of whom that can be properly said.” DM/ ML

If this has sparked your interest try to find The Life and Works of Charles Bell by Phillida Brooke Simons (Fernwood Press).

Painting by Charles Bell. Image: Supplied

Painting by Charles Bell. Image: Supplied