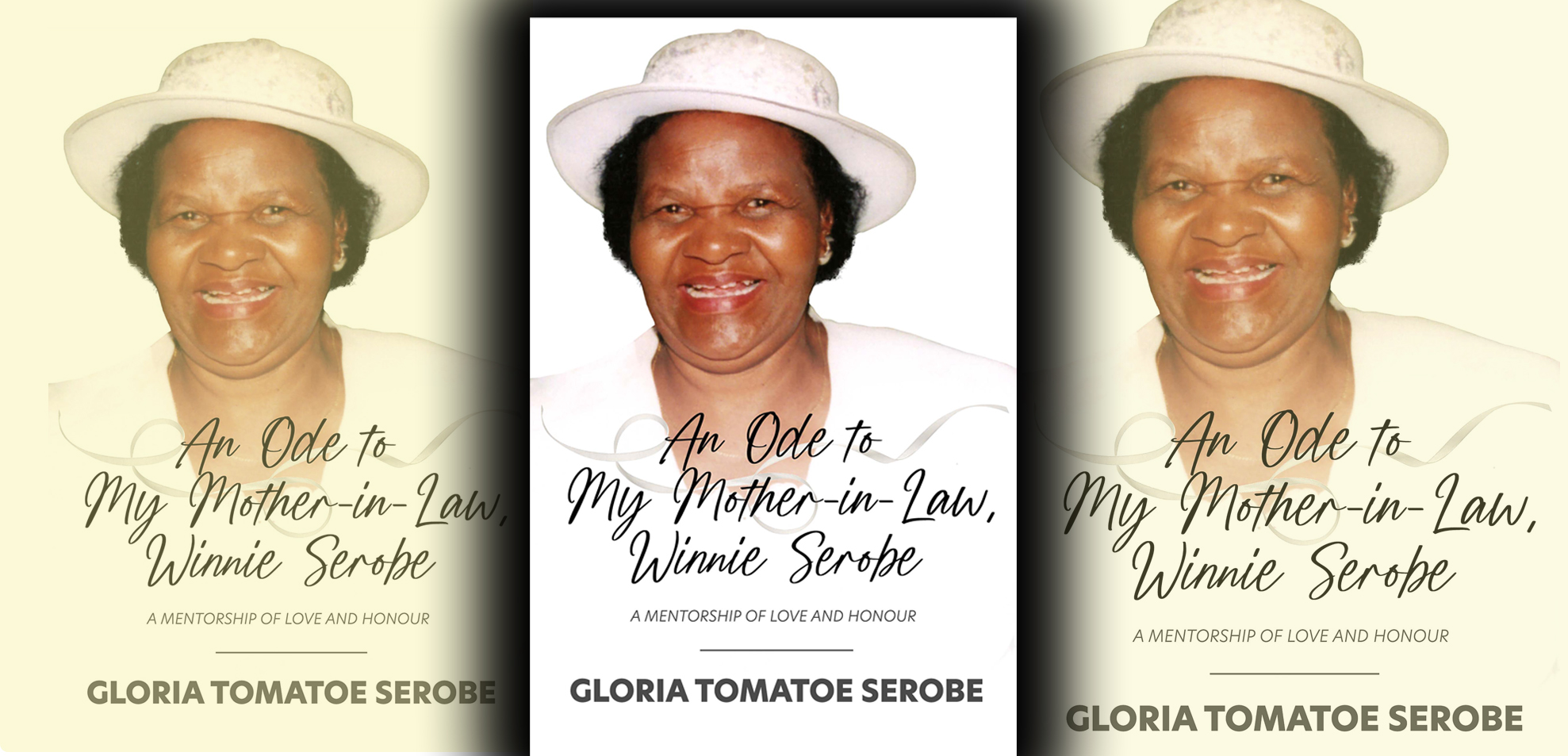

“This book is dedicated to a woman who held my hand with warmth, nurtured my heart with love and led me to a path of family love… That woman is my mother-in-law, the late Mrs Winnie Serobe.”

So reads the dedication page of Gloria Serobe’s book. In his foreword, Gaur Serobe – the author’s husband and son of the book’s subject – suggests that this book is about “an ordinary love between two exceptional women, an ordinary bond between two women that I love deeply”.

However, when one reads the 152 pages of the book, drinking it all in – and when one considers the fortitude with which Winnie Serobe (née Radebe) struggled with the apartheid-imposed limitations she was up against – one must conclude that there was nothing ordinary about Winnie Serobe.

Nor is there anything ordinary about Gloria Serobe (née Ndaliso) – the book’s author. Not even the word “extraordinary”, which Gaur Serobe later introduces, effectively captures the relationship between the woman from Matukaneng ko Thaba Nchu – the late Mme Mma Winnie Serobe aka ‘Sinky’ – and her daughter-in-law, Gloria.

Beyond the myth of the wicked mother-in-law

This book takes on and tries to overturn aspects of global and African cultures which are steeped in centuries of myths, fables, and children’s stories built around the character of the wicked mother-in-law. This character is the butt of jokes, the target of stigma and the object of vendettas.

The reason so much hate is directed at the mother-in-law is simply because she is a woman. If that was not the case, most cultures would also have an equivalent stereotype of a wicked father-in-law.

The myths and stereotypes of the “wicked witch” of a mother-in-law persist across many cultures as part and parcel of patriarchy and misogyny which intersect and overlap with other forms of bigotry, including racism and various forms of economic and cultural exclusion.

For these and many related reasons, we must refuse to take this short book of Gloria Serobe at face value. It is more than a conventional biography – more than an expanded diary or description of family trees.

The 26 chapters, packaged into five parts, are brief but punchy, strategically approached and purposefully unfurled, and the stories therein are told in evocative and thought-provoking ways. It is much more than an inward-looking feel-good story about two women whose experiences were merely a flash in the pan.

This is a book about the evolution of the black South African family and its struggle to overcome the limitations of both black culture and the economic stranglehold of apartheid. In this sense, at least, the book is not merely a manual about “daughter-in-lawship”, “mother-in-lawship” or “good-wifeliness”.

And we must not let the beautiful story of the ties that bound a mother-in-law to her daughter-in-law trick us into thinking that this is an apolitical book.

There is an unspoken, harder core to this book.

A woman in touch with the pulse of black life

The story of Winnie Serobe (and Gloria Serobe) is the story of the socio-political condition of the black woman in both urban and rural South Africa in the late 1980s up to the first decade of the 21st century.

In the same way that Ellen Khuzwayo’s standard-setting classic, “Call Me Woman”, was, according to Nadine Gordimer, more than just a book about one person, Gloria Serobe’s book about Winnie Serobe is not just the story of one woman. It is the story of “a woman who was connected to the South African psyche and that of black people in particular” – a woman in touch with the pulse of black life and the circumstances surrounding black women.

The book contains many brief but fascinating portraits of icons other than its central subject. Consider the character of Gaur Radebe – the grandfather of Gloria’s husband who was named after him. Gaur was the only other black person at Sidelsky’s law firm at which Nelson Mandela articled.

Among many other prominent roles, Gaur Radebe, like Walter Sisulu, was a mentor to the young Nelson Mandela. Consider Moses Mauane Kotane – former Secretary General of the South African Communist Party and former Treasurer General of the ANC. He was married to Rebecca, Winnie Serobe’s aunt.

Winnie Serobe was a force of life in her own right. There are not many mothers-in-law who will go searching for and choosing a wedding dress with and for their daughter-in-law. Winnie Serobe not only did that, but she also paid for the dress.

Some mothers-in-law would grab the opportunity to teach their daughters-in-law how to do domestic chores – especially if the daughters-in-law happen to be “not that strong in house chores”, as Gloria Serobe was. Instead, Winnie Serobe mentored, networked and enlisted her daughter-in-law into volunteerism and community service with a view to creating a more equitable society.

Winnie Serobe took her daughter-in-law to meetings of the YWCA, Women’s Club, Black Consumer Union, Housewives League and the South African National Council for the Blind. How many mothers-in-law would introduce their daughters-in-law to the Ellen Khuzwayos, Joyce Serokas, Sally Motlanes, Nonia Ramphomanes and Albertina Sisulus of this world? How many mothers-in-law would school their daughters-in-law in the strategies and tactics of mobilising “the poor to help the poorest”?

On the face of it, this is a book about a mother-in-law who taught a daughter-in-law how to be a good bride and how to “build a home”, but the book also sharply poses the question of “why women have to carry this responsibility [of building a home] – almost on their own”.

This is a book whose author, together with other women, achieved the ground-breaking feat of establishing a “retirement fund for domestic workers with Old Mutual in December 2007”. And they got employers of domestic workers as well as other players in corporate South Africa to contribute to the fund.

A name written into hearts

It is remarkable that in this book the author only begins to write – rather briefly – about herself on page 91. And the little that she writes about herself is framed as her humble attempt to multiply her mother-in-law.

And yet Gloria Serobe is a respected South African community builder in her own right. She established the Greenhouse Child Care Centre for young mothers – a seven-day-a-week facility with a 24-hour accommodation option. And guess who came out of retirement to assist with running the centre? Mother-in-law, Winnie Serobe.

In 1992, Gloria Serobe was awarded the Eskom Woman of the Year for the most innovative community project. And guess who else was honoured on that occasion? None other than the indomitable and inimitable Ellen Khuzwayo, who received the Lifetime Achiever Award.

When she was asked by then-president Thabo Mbeki and the leaders of 58 non-governmental organisations to join and chair the presidential working group for women, Gloria Serobe felt validated and energised. Fortunately, these accolades were showered on her when her mentor and mother-in-law, Winnie, was still alive.

But perhaps her greatest sense of self-actualisation came when Gloria Serobe, together with other women, “set out to confront [Eastern Cape] poverty head on”. In part, that is how and why Wiphold (Women Investment Portfolio Holdings) was born. Wiphold went on to prove, among other achievements, that “large-scale commercial farming can be financially sustainable on communal land”.

After four of the shorter chapters in which she briefly showcases the kind of work her mother-in-law inspired her to accomplish, the author swiftly returns to the subject of the book – her mother-in-law.

Lyrically and with a palpable sense of appreciation, Gloria Serobe describes the legacy of her mother-in-law: “We may not find the name of Winnie Serobe in any of the country’s annals of history. But you will find her name on the lips of her children, for whom she sacrificed everything to ensure they were taken care of, nurtured and educated.

“You will find her name in the hearts of the young women she encouraged to make different choices that changed the trajectory of their lives forever. You will find her memory in the community of Diepkloof and others, where she worked so tirelessly to make a difference to the lives of ordinary, vulnerable, and sometimes ‘unseen’ people.”

Can a daughter honour a mother better? Can a daughter-in-law show more gratitude to her mother-in-law? Can a woman honour a fellow woman more profoundly? Can a human show deference to another more splendidly? I doubt it. DM