This article is an extract from “Multi-stakeholder analysis: South African Covid-19 vaccine procurement contracts” and was written by the Multidisciplinary Stakeholder Analysis Group, led by Health Justice Initiative (HJI). The group is made up of the following organisations:

- Health Justice Initiative (HJI) – South Africa; Fatima Hassan and Marlise Richter;

- Health Law Institute, Schulich School of Law at Dalhousie University – Canada; Matthew Herder;

- O’Neill Institute at Georgetown University – USA; Matthew Kavanagh and Luis Gil Abinader;

- Public Service Accountability Monitor at Rhodes University – South Africa; Jay Kruuse;

- Global Justice Now – UK; Nick Dearden;

- Health GAP – USA; Professor Brook Baker;

- Expert IP Lawyers – India; Roshan Joseph and Leena Menghaney;

- Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge – USA; Tahir Amin; and

- Public Citizen – USA; Peter Maybarduk.

Globally, at least 14 million people lost their lives in two years (2020-2021); these are excess deaths associated with the Covid-19 pandemic. Many of these deaths were preventable.

The uneven and unfair allocation of vaccines to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic globally, has been correctly described as a “moral failure” including by the World Health Organization (WHO). In that time, the majority of black and brown people in the Global South struggled to access life-saving vaccine supplies. Many parts of the Global South especially, saw declining public health outcomes, premature death and suffering, and terrible socioeconomic devastation.

By early February 2023, within three years, according to Our World in Data, 69.7% of the world population had received at least one dose of a Covid-19 vaccine, 32 billion doses have already been administered globally, and 28% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose.

During the Covid pandemic, and given this global context on access inequity, HJI tracked vaccine equity, supplies, and access for South Africa (SA). For the better part of 2021, the HJI found that SA either had negligible or staggered access (also referred to as a “drip-drip” supply system) for several reasons.

Thus, for months, while people were getting vaccinated in the Global North and elsewhere, with even two shots of vaccine doses, people in SA were waiting for vaccine supplies and for the national vaccine programme to properly kick off (save for a few hundred clinical trial participants, a few hundred thousand healthcare workers via a J&J donation/“study programme” called Sisonke, (and oddly and unfairly, if not unethically, through that programme, a handful of sports people and celebrities too).

While SA scientists and researchers led global efforts on genomic surveillance, detecting variants first, well ahead of other countries in the Global North, the SA Government led a bold proposal on a waiver of IP rules at the World Trade Organization, with others. SA also supported and took part in at least four clinical trials, contributing to the global generation of knowledge for vaccine approval and use too. People in SA volunteered for trials for Pfizer, J&J, AstraZeneca and Novavax.

But for access to scarce supplies, SA was placed in the back queue, the “African queue’’, like apartheid, this time by powerful companies, where access to the very same vaccines tested on people in SA was delayed or denied.

Subtle threats invoked to block the IP waiver proposal led by SA

Per media reports, the same companies also lobbied and, in some cases, invoked subtle threats to block the IP waiver proposal led by SA. For example: Politico previously reported that government officials in Belgium were lobbied by J&J representatives who “asked” them not to support the waiver proposal, in return for retaining their investments and plants in Belgium:

“Is that a direct threat? I don’t know.” The adviser to the Belgian prime minister spoke calmly as they recounted a lobbying phone call from 2021, but the contents of the conversation are extraordinary. The call was from a spokesperson for Janssen, the Belgian-founded pharmaceutical arm of J&J that developed the company’s single-shot Covid-19 vaccine. According to the adviser, the spokesperson warned them that if Belgium supported a radical proposal made by India and South Africa at the World Trade Organization, then Janssen might rethink its vast billion-dollar research and development investments in Belgium.” [Politico, emphasis added]

The complex issue of vaccine apartheid and nationalism has been extensively set out in the main set of legal papers for the HJI in the case at hand, and by several leading CSOs in multiple other reports, academic journals, health publications, opinion pieces, and media articles and stories and by the WHO, since late 2020. The same issue has been emphasized on multiple occasions on global platforms by SA’s President, Cyril Ramaphosa as well, most recently at the World Leaders’ Summit for a New Global Financing Pact, where he referred to Africa being akin to “beggars” (for vaccine supplies).

Why are the contracts important?

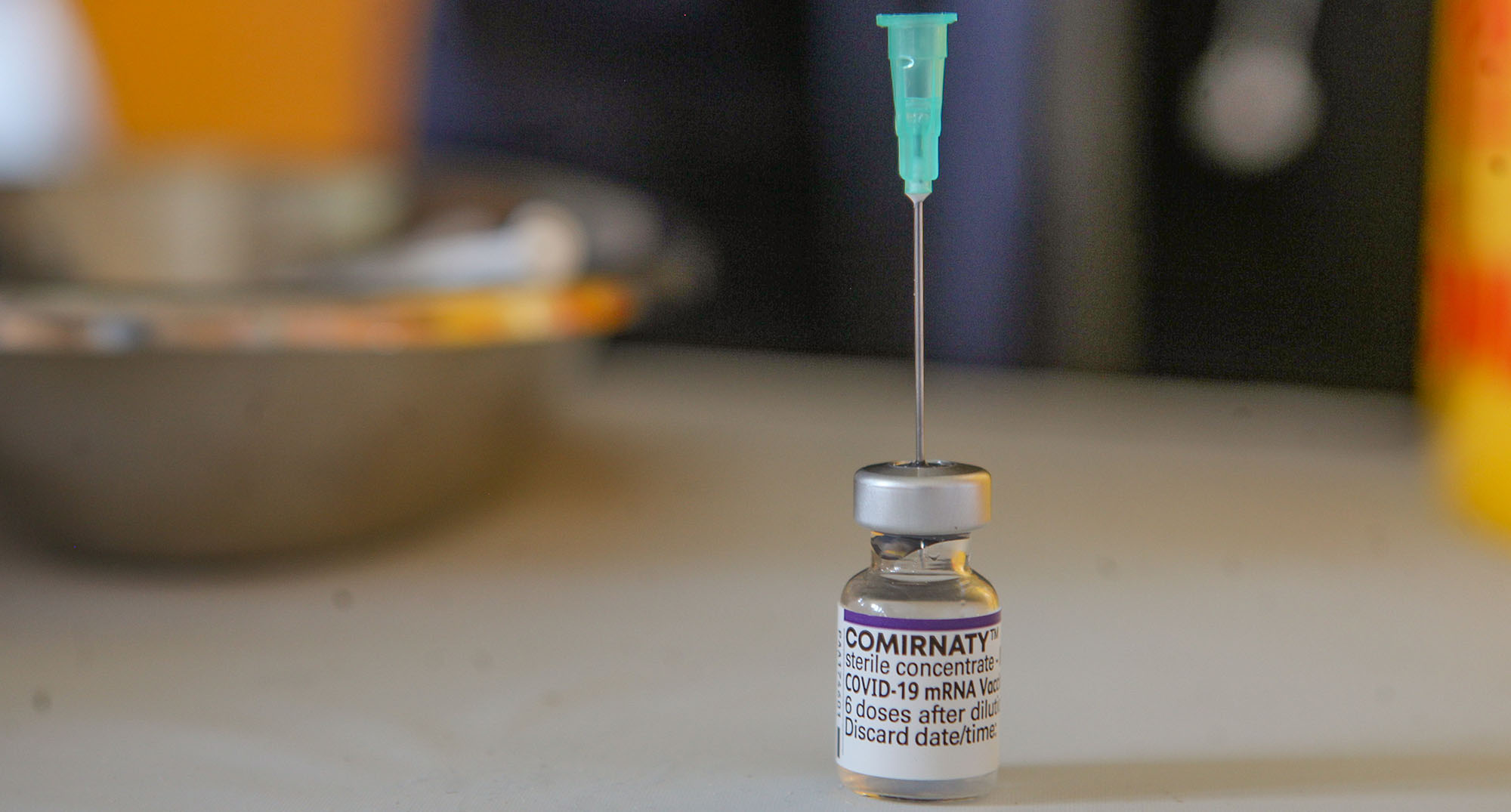

As of 4 June 2023, more than 38 million Covid-19 vaccines doses had been administered in SA. Since late 2021, SA has received several millions of vaccine doses by directly buying from pharmaceutical companies, or through the Covax facility administered by Gavi or by receiving donations. These vaccines have been procured at great cost.

The public has, until now, not known the content of the contracts, nor the complete details of the contracting parties, nor the details of unsuccessful or paused negotiations with other entities too. In other parts of the world, civic groups, NGOs, public interest lawyers, and journalists have also attempted to obtain copies of contracts entered there, and using a variety of means, successfully secured a combination of unredacted/redacted versions through leaked copies or information access requests and legal filings. We therefore hope that the precedent set by the judgment of Millar J – involving the HJI and Minister of Health – in the Gauteng High Court will ensure that in future pandemics, this information is automatically placed in the public domain and transparency is prioritised.

Paragraph 2 of Millar J’s judgment is clear and unambiguous – about the role vaccines play in mitigating a health crisis and in managing a global pandemic (emphasis added):

In this application, it is not in issue between the parties that Vaccines play a pivotal role in mitigating the consequences of Covid-19, by preventing death and controlling the spread of the virus. They are a central element of the global – and the South African – response to Covid-19, prompting a worldwide effort to immunize billions of people. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has emphasised the importance, to trust in the vaccination programme, of governments demonstrating their ability to procure vaccines and to develop effective and inclusive roll-out plans. It recommends that such plans should be open to public scrutiny and require proactive disclosure of information.

Because of this judgment, and the decision by the minister not to appeal it, by 31 August 2023, four contracts were handed over to the HJI’s legal representatives. On 5 September 2023, it was available to download from the HJI website, accompanied by a multistakeholder analysis.

A bit of history…

In mid-2021, the HJI requested and then filed access to information requests (using the “Promotion of Access to Information Act” – PAIA – a freedom of information law, in SA) to obtain copies of the Agreements, among other documents, which request, and internal appeal were refused or rejected by the department.

HJI also tried to get the contracting parties’ details and complete identities, but these requests were also “rebuffed” [per Millar J]. As a result, in 2022, the HJI filed legal papers against the SA Minister of Health and the National Department of Health’s Information Officer. It was argued on 24 July 2023 in the Pretoria High Court in Gauteng before Millar J. Shortly thereafter, on Thursday, 17 August 2023, the High Court ruled in HJI’s favour in its bid to compel the department to provide access to the Covid vaccine procurement contracts and other documents.

The Court [Millar J], in a groundbreaking judgment, ordered the disclosure of: a) Copies of all Covid-19 vaccine procurement contracts, and memoranda of understanding, and agreements (we refer to this as “part 1”); and b) Copies of all Covid-19 vaccine negotiation meeting outcomes and/or minutes, and correspondence (we refer to this as “part 2”); within 10 court days of the judgment (31 August 2023).

The minister did not pursue an application for leave to appeal the judgment: But the department’s legal representatives requested an extension until 29 September 2023 for the handover of the “part 1” and “part 2” documents.

HJI granted the extension for the “part 2” documents (negotiation meeting outcomes, minutes, and correspondence) but did not grant it for the “part 1” documents (Contracts, MOUs, and Agreements).

A few days ago, on Thursday, 31 August 2023 there was a handover of documents to HJI’s legal representatives purporting to be the “Contracts, MOUs, and Agreements” (part 1) with three companies (Janssen/ J&J, Pfizer, the Serum Institute of India (SII), and with one not for profit initiative – Gavi, for COVAX).

The documents were not redacted. The HJI now awaits the “part 2” documents, due by 29 September 2023, which date constitutes the extension period to which HJI has agreed.

On receiving the “part 1” documents, the HJI, with a diverse range of academics, lawyers, and researchers from different organisations and universities, immediately worked on verifying what was handed over, and since the evening of 31 August 2023, studied and reviewed the documents, to provide the following joint analysis (preliminary):

- a) The HJI chose this approach because this case is of grave importance, both locally in SA, and globally, for transparency norms in the domain of vaccines and pharmaceuticals. As such, HJI drew on its partners to assist with the review;

- b) At a time of social media and other forms of disinformation and anti-science messaging, which is anti-evidence, and where anti-vaccine groups are becoming more vocal on social media, we have chosen this path to share proper and accurate information with the public; and

- c) Our starting point is that approved vaccines are safe and effective, can save lives, and that if Covid vaccines were more speedily available at the RIGHT time in the Global South, in 2021 especially, and with a greater focus on broad universal and unencumbered technology sharing, immediate suspension of IP rules, and proper attention to public health equity needs, then the devastation on our societies and health sectors in particular during that time, in SA, everywhere in the Global South, and beyond, could have been mitigated better.

At the outset it is important to note that this analysis is based on four sets of agreements provided by the state to HJI in terms of the court order and that the outstanding documents are due to be delivered by the end of September 2023.

There are four contracts

This being the four entities that SA procured and/or received vaccines from during the Covid-19 pandemic, where payment was made from the national fiscus. Agreements related to the donation from the US Government of Pfizer supplies are not included here.

The four Contracts are thus for: J&J/Janssen, Pfizer, SII (licensee of AstraZeneca), and COVAX (Gavi).

Within the four contracts, while the following documents are referenced for COVAX/Gavi (“Terms and Conditions”; “Allocation Framework”) and for Pfizer (“Indemnification Agreement”), they were not attached and/or included in the handover of 31 August 2023. If separate non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) were signed for any or all the parties, those NDAs have not been provided either. HJI’s legal representatives have accordingly requested confirmation of, or copies of same. All four contracts were legally obtained as part of a court-ordered process. These contracts were thus not “leaked” to the HJI. The contracts, per the court order, are not redacted, and HJI has since 5 September 2023, shared them on its website for public viewing.

After reviewing and studying the documents making up the four contracts, we found that in all four contracts, the pernicious nature of pharmaceutical bullying and Gavi’s heavy-handedness were plain: the terms and conditions are overwhelmingly one-sided and favour multinational corporations and preserving their intellectual property (IP) empires.

Extractionist terms and conditions undermine SA’s sovereignty

This placed governments in the Global South, and in turn, the people living in these countries, in the unenviable position of having to negotiate scarce supplies in a global emergency (2020-2023) with unusually onerous demands and conditions, very little leverage against late or no delivery of supplies, and inflated prices – all under conditions of strict secrecy. SA’s sovereignty was, in short, completely undermined. This should never happen again. We have argued that it is unconscionable, imperial, and unethical.

The most egregious example of this, in our review, has been a multinational pharmaceutical company (Johnson & Johnson/J&J) trading scarce or very delayed supplies for extractionist terms and conditions that undermine national sovereignty – precluding SA from imposing any export restrictions or bans. This was mainly to benefit their bottom line or patients in Northern countries first: in Europe, not Africa. This requires further investigation.

Equally problematic is another very profitable multinational company, Pfizer, which extracted over-the-top concessions from SA, shirking its own liability, and worse, demanded that it retains 50% of the ‘’first payment”, even upon its own default to register or deliver the vaccines to SA. Pfizer also included a one-side disclaimer of non-infringement of other right holders’ IP, in effect, demanding the very kind of IP waiver that it vehemently opposed be granted to vaccine developers in the Global South.

By all reasonable accounts and based on what was agreed to with SA, COVAX overpromised and under delivered for SA (and elsewhere), supplying even fewer vaccines than what the US Government donated to SA in 2021, when it mattered the most. Further, South Africa received no price guarantee under the COVAX Agreement: while the all-inclusive weighted average estimated cost per dose was $10.55, South Africa had the right to reject doses costing more than $21.10.

J&J contracted to charge SA $10 per vaccine dose, while the EU reportedly paid $8.50 – and the “non-profit price’’ was in the range of $7.50. It is not clear from the contracts if, and when, and for what period, SA was not charged the price contained in the contract/refunded the balance in price difference, as J&J has since claimed that it only charged SA the “not-for-profit price’’.

For the SII, it is also likely that SA overpaid compared to European countries by at least more than two-and-a-half times! In the UK and EU, AstraZeneca charged £2.17 and £2.15, respectively, whereas SA’s contract included $5.35 per dose.

The contracts also required SA to seek “permission’’ to divert or donate or sell doses which have already been paid for by the South African public, despite the benefit to other poorer countries or buyers. Frankly, in a global pandemic, this is paternalistic and imperialist, harms public health programmatic planning, and deliberately reduces the autonomy of African states.

In particular, J&J, Pfizer and COVAX did not commit to supply volumes and delivery dates, making it increasingly difficult to plan and run a timely and proper vaccination programme.

A dangerous precedent for future pandemic readiness measures

Our analysis has set out extensively out why this type of “take it or leave it” contracting signals a dangerous precedent for future pandemic readiness measures and systems, and why this level of bullying and lack of transparency has no place in any democracy. It requires systemic redesign.

The point of an advance purchase agreement is to have a minimum level of certainty for South Africa to order and purchase vaccines or medicines and receive them timeously. These contracts belie that purpose and attempt to shroud that failure in secrecy.

And regrettably, this is not a once-off Covid-related modus of operating: at present, even more pharmaceutical corporations are insisting on NDAs – with broad confidential information clauses, and including them more aggressively in supply agreements to suppress the disclosure of pricing and supply terms, particularly in negotiations covering monopoly products such as HIV medicines.

It is also unfortunate that the South African Government spent almost two years resisting disclosure, for the main benefit of big pharmaceutical corporations and Gavi - COVAX. Lack of timely public access to these contracts created mistrust and limited public accountability action towards these corporations during a global pandemic. It also created opportunities for price variations and enabled these multinationals to impose coercive terms on the SA Government.

This deference to and fear of pharmaceutical power, in the middle of a crisis, in a constitutional democracy, should be of deep concern to the global public health community. It shows how much power was put into the hands of private sector actors and how few options governments had, when acting alone, in the middle of a pandemic.

This is not a problem that can be solved by a single government but requires a regional and global solution and the exercise of state sovereignty.

Unless acted upon with clear, legally binding international agreements, not whimsical pledges, we will arrive at the next pandemic with little more to enforce fair terms than platitudes and scathing press statements from the minister and president in SA and other world leaders in the Global South.

Transparency and fair terms on quantities, price, and delivery must be deliberated upon in Pandemic Accord negotiations and revisions of the international health regulations currently under way, and at the upcoming United Nations General Assembly.

Thankfully, the courts in SA have mitigated and addressed some of the uglier sides to contracting in the Covid pandemic, with this groundbreaking judgment.

While the HJI case and Millar J’s judgment have opened up the secret Covid-19 vaccine procurement contracts to foster transparency and accountability in public procurement of health goods, hopefully this will have far-reaching implications, not just for the next set of pandemic procurement negotiations and contracts/agreements here and elsewhere, but also for the substantial amount of procurement due to take place under SA’s future National Health Insurance system.

Finally, we therefore call on governments in the Global South, the boards of these and other pharmaceutical corporations, as well as their wealthy shareholders, and the Geneva-based not-for-profit initiatives, to take the necessary steps to ensure that this type of bullying and extremes of non-disclosure, and secrecy are not repeated in the next pandemic. We need open procurement processes, not secretive ransom negotiations. DM