A public apology can be a very powerful mechanism for a politician, as well as a good way to bring closure to a scandal or controversy in a struggling democracy, so Zwane’s failure to offer one is rather unfortunate.

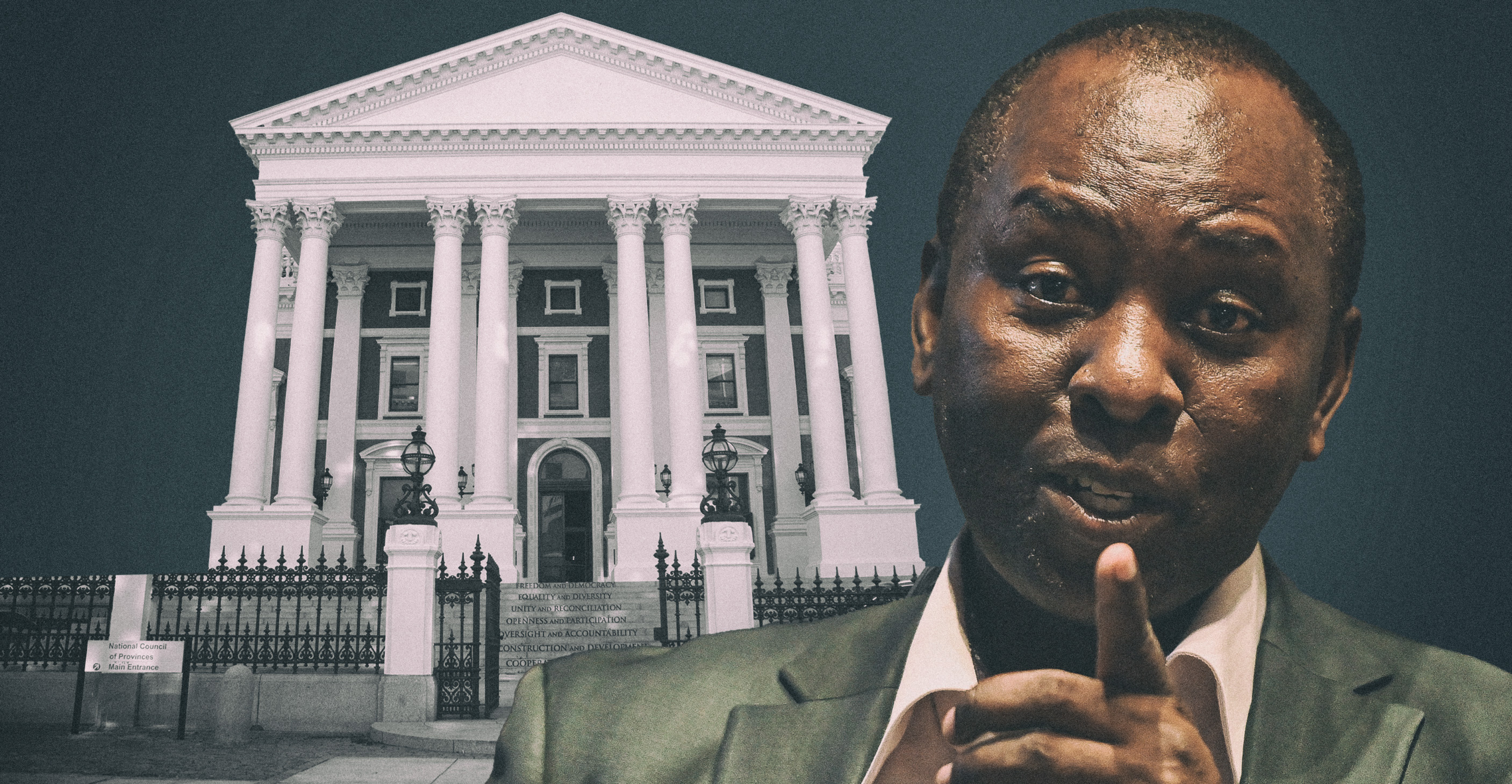

Last week, the National Assembly adopted the findings of Parliament’s Joint Committee on Ethics and Members’ Interests that Zwane had not disclosed the benefits he received from the Guptas, and that he had appointed two of their business associates to adviser positions. The committee and the ANC’s chief whip said he must apologise for his actions.

Zwane failed to attend the parliamentary sitting and did not apologise. Never before has a member of SA’s Parliament failed to publicly say sorry when ordered to do so.

This unprecedented move suggests that Zwane does not accept the authority of the National Assembly, of which he is a member, and that he rejected the findings of the committee.

Still, there have been times when the opportunity to apologise was taken. Former president Jacob Zuma eventually had to apologise over Nkandla, after the Constitutional Court ruled that a Public Protector’s remedial action was binding.

He said: “The matter has caused a lot of frustration and confusion, for which I apologise on my behalf and on behalf of government.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ABHrFrGPX48

Also, the former deputy minister of higher education, Mduduzi Manana, resigned after being filmed assaulting a woman in a parking lot in 2017. While he did not use the words “I’m sorry” or “I apologise” in his “address to the nation”, there can be little doubting the tone of his comments, and that an apology certainly appeared to be meant.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e_TQtZ0Hx_4

Later, he promised publicly to apologise directly to his victim.

Former communications minister Dina Pule also did what Zwane failed to do, when ordered by the same parliamentary committee as Zwane to apologise in Parliament. This she did, and was immediately embraced by ANC MPs.

There can be no doubting the power a political apology can have.

As in many relationships, saying “sorry” can allow things to move on and end an issue which could otherwise continue to consume a politician.

And many people like to see someone apologising. Strangely, even if it is someone who has done something seen as very wrong, an apology can almost grow their support.

Despite all of that, it does not appear to happen very often in our politics. Why not?

It is interesting to examine countries where apologies happen often.

Apologise, resign, return…

In the UK, for many years, there was almost a formula for this kind of thing. There would be a scandal and the person concerned would apologise and resign. Within a relatively short period of time, say six months, they would come back into the government.

Tony Blair, famously, had to let Peter Mandelson, one of his closest political allies, resign twice.

There is a good example of a very powerful and cynical use of a public apology. Recently, Suella Braverman was able to resign from the short-lived government of Liz Truss and appeared to use her resignation letter to make a point about taking responsibility for her actions. That then forced Truss to resign, while Braverman was appointed back into the government just six days later when Rishi Sunak was elected as Prime Minister.

This shows how an apology, with its particular power, can be a useful tactic.

But not in the US.

The reason is that the US is simply more polarised: if you “give in”, you are not just accepting you were wrong, but your entire side of society is let down. In other words, someone will not apologise because it would allow the other side in the culture war to somehow win.

This suggests that the deeper the levels of polarisation in a society, the less likely you are to see a politician apologise in public.

Given that the lived experience of apartheid is still very much the defining feature of our present, the fact there was no real apology for that period immediately comes to the fore.

The failure of the last apartheid president, FW de Klerk to apologise for the policy is one of the reasons he became such a controversial figure towards the end of his life.

After he died, a video was released of him saying, “I, without qualification, apologise for the pain and the hurt and the indignity and the damage that apartheid has done to black, brown and Indians in South Africa”.

If he had made the same gesture while still alive, he might have been seen differently.

The shameless ones

There is another element, which is impossible to quantify.

Some people simply give no evidence of having personal shame and appear to believe that they could never be in the wrong, almost as if they believe they are not accountable to any other human beings.

Former US president Donald Trump is one example of this, former UK prime minister Boris Johnson is another.

It is interesting to consider Zwane’s position here.

He could fall into this category of shameless people. Or, he may feel that if he does apologise, he is letting down a group of people who were all a part of the State Capture effort.

In the meantime, it is important to consider whether public apologies will be heard more often in the context of SA politics.

There was a time when it was unheard of for a South African Cabinet minister to resign from office. Until 2017, there had been hardly any (the one prominent exception was the current Finance Minister, Enoch Godongwana, who resigned as deputy trade and industry minister in 2012).

But in 2017, Manana resigned, followed a year later by Nhlanhla Nene. He stepped down as finance minister after it emerged he had lied about never meeting members of the Gupta family. A month later, the then Home Affairs Minister Malusi Gigaba stepped down following a high court finding that he had lied under oath (among other issues…).

Then, in 2022, Ayanda Dlodlo resigned as public service and administration minister, though she was taking up a position at the World Bank.

This suggests that political resignations from the government are becoming less uncommon. As resignations are often (but not always) the result of alleged wrongdoing, it may be that one follows the other.

This would be a positive development — both for our politicians and for our democracy. DM