Yes, it is true that by the time Athol Fugard hit his stride as a masterful storyteller of contemporary South Africa, another theatrical current, “township theatre” by such people as Gibson Kente, was already touring in the country’s black townships.

Still, most (white) theatregoers largely remained content with British and US imports, most often light dramas or musical theatre (or the occasional hits like “Equus”). Few, if any, works appeared on stage to illuminate the true reality of South Africa’s human circumstances under apartheid. This is precisely where Fugard’s genius became something both rare and precious.

Instead of lighthearted comedy or stereotyped works, Fugard captured the pain inflicted upon people by the circumstances of the apartheid regime, sometimes mixing it with the lessons of his own experiences working as a white South African in his mother’s tearoom or as a clerk in a passbook court. (A passbook was the ID document black South Africans were forced to carry.)

Fugard also found ways to collaborate with a rising generation of angry, young black actors. Despite this anger, he still infused in his writing the flickers of optimism that proclaimed that even in the darkness that surrounded his characters, there might yet be light.

He wrote (including several collaborative efforts with the actors John Kani and Winston Ntshona) some 30 dramas, essays and the acclaimed novel “Tsotsi”, a work that later became an award-winning film. Fugard acted in some of his plays in SA and abroad, and appeared in several international films, including “Gandhi”, where he portrayed the South African general Jan Smuts, Winston Churchill’s military adviser.

For this writer, as a young US foreign service officer, living in South Africa on his first assignment there in the mid-1970s, seeing Fugard’s “Boesman and Lena” and “Blood Knot” was an extraordinary eye-opener. I was already acquainted with the textbook facts about South Africa, but seeing the human elements of apartheid portrayed on stage about people caught at the margins but driven to imagine something different, yet constrained from ever reaching it, was a revelatory experience.

Over the years, scripts continued to flow from his pen. These included those workshopped together with Kani and Ntshona, two young actors of the Serpent Players, such as “The Island” and “Sizwe Banzi Is Dead”.

For other works, Fugard drew upon his lifetime, such as with “Master Harold and the Boys”, pinpointing the fault lines between races in South Africa — along with the unrealised hopes of bridging those gaps.

Even in the dark times, there could be a slightly more hopeful side in such dramas as “Playland” and “My Children, My Africa”. There, the glimmers of a hoped-for evolution could be faintly discerned amid the wreckage of an apartheid apparatus beginning to come apart.

Onrushing mortality

In his later years, with works like “Exits and Entrances” and “The Shadow of the Hummingbird”, audiences saw another Athol Fugard. This time it was a man trying to grapple with onrushing mortality and how to pass life’s torch on to a future generation.

In this last period of his writing, Fugard had moved beyond that earlier call by the novelist Nadine Gordimer who had argued the role for a white writer in South Africa was to focus on the politics of the place and its peoples’ struggles with it. In Fugard’s last works, he reached for attempts to answer the meaning of life.

Over a decade ago, David Smith, then The Guardian’s Africa correspondent, interviewed Fugard the morning after the opening of “The Shadow of the Hummingbird”.

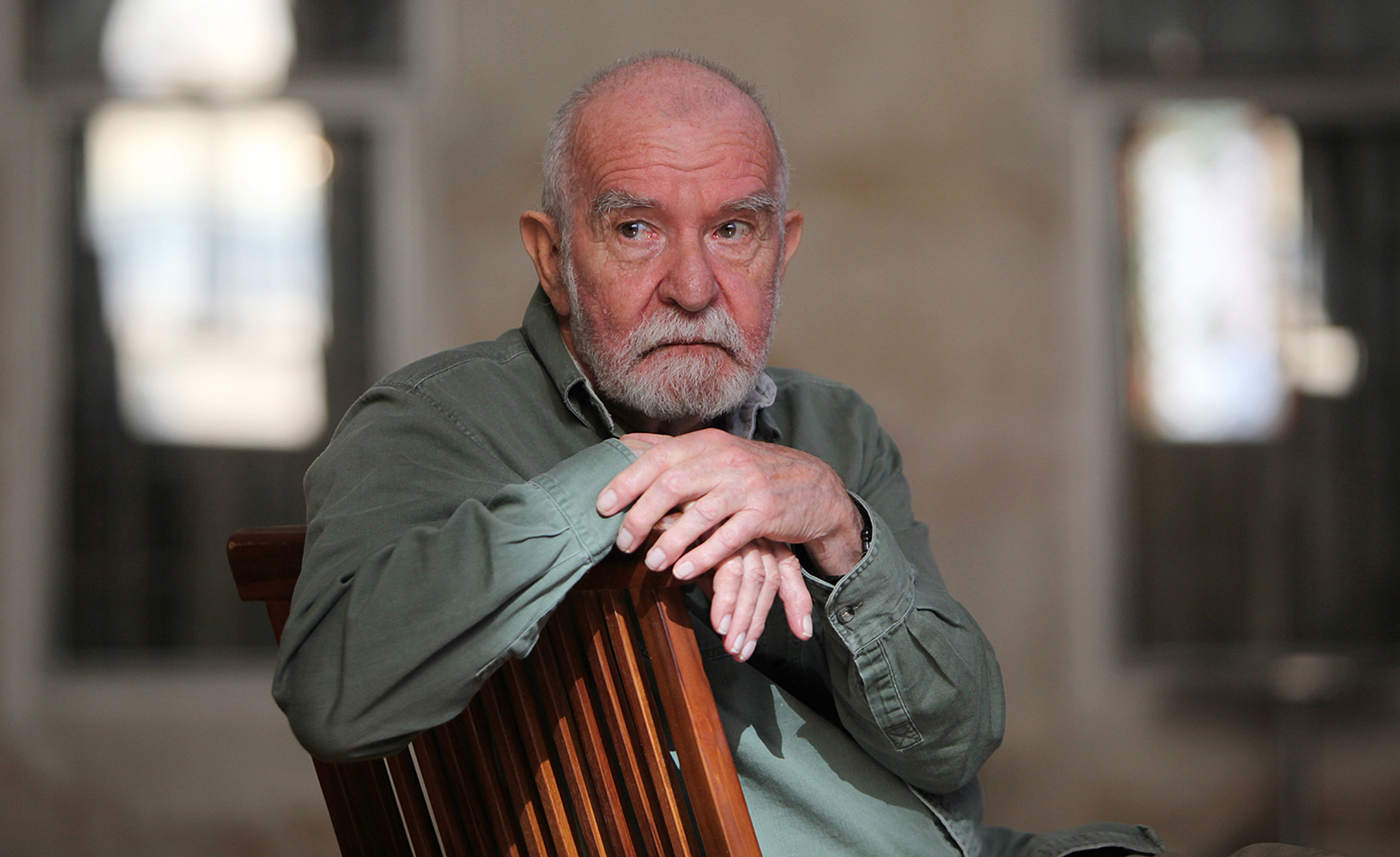

Smith wrote, “Yet the following morning, in a discreet guest house down a discreet street, Fugard is firing again. South Africa’s greatest ever playwright turns out to be also one of its most likeable. Ebullient and gregarious … he settles into a seat on a veranda overlooking a manicured garden, lights a pipe and is interviewed against a ripple of birdsong; it is a scene that could be taken from one of his recent elegiac works.” A man surprisingly content with his work and his life.

For many years, Fugard has been widely recognised as South Africa’s pre-eminent playwright. Beyond South Africa, his works continue to be staged in Britain, the US, Canada, Australia and elsewhere, underscoring a global reputation. Some of his works, such as “Blood Knot”, “Sizwe Banzi Is Dead” and “The Island”, continue to be staged in South Africa, despite their roots in an earlier era of anguish for so many South Africans.

His ability to speak to those very large things via the conversations, the confessions and those revealing monologues by ordinary people, may be why his works connect with audiences two generations beyond the old regime. No one carries a passbook anymore, but it remains easy to relate to the title character of the play, Sizwe Banzi, as he hopes for a lightning strike, a deus ex machina that will release him from his agonies.

In its obituary of the playwright, The New York Times noted that “in none of these plays, however, is apartheid the addressed subject. Rather, it is the saturating reality of the plays, the societally sanctioned philosophy — like American capitalism in Arthur Miller’s ‘Death of a Salesman’ — that informs the lives of the characters.”

Not surprisingly, Miller’s play is another modern work whose contents and characters also continue to be staged around the world.

Scourge of the regime

The Guardian’s Smith added, “Fugard fought the liberation Struggle as playwright and impresario. He organised a multiracial theatre company, supported a boycott of South African playhouses in protest at audience segregation and was a scourge of the white minority regime. In 1961, in ‘The Blood Knot’, he and Zakes Mokae became the first black and white actors to appear together on a public stage. Mokae would be a close friend and creative partner.

“‘I remember taking a train from Cape Town to Johannesburg where we were going to do the play ‘The Blood Knot’, and Zakes had to travel third class and I was of course white and could travel first class. What do you do? Don’t go? No! The dilemma of having to accept the compromises in order to get the work done to raise the issues that white South Africans were reluctant to raise — the issues that were happening in the country.

“‘I ended up having to carry Zakes’s passbook — that was a dreaded document — because he had refused to carry it. So I said, “You give it to me,” because you are going to end up in jail and he did many times when he was by himself and I had to bail him out.’”

Beyond the extraordinary impact he had on his audiences, Fugard had a galvanising impact on the actors, younger playwrights and directors who fell into his orbit.

Paul Slabolepszy, a distinguished dramatist and actor, said of Fugard when they first met on the roof of the Space Theatre in Cape Town — the first integrated theatre venue in SA — back in 1972, “This is where I met the man who spoke of the light and the dark and all shades in between. The man who told me to follow Barney Simon back to Joburg after Barney and Mannie Manim had come down to see us in that first dangerous, going-it-alone year when the land we lived in was bleak.”

(Three years later, Simon and Manim set up the Market Theatre in Johannesburg.)

Slabolepszy added, “I am one of the remaining few who witnessed the very first performance of ‘Sizwe Banzi Is Dead’ at the Space in Cape Town in 1972. It was the play that launched Athol, John Kani and Winston Ntshona on to the global stage and I remember it like it was yesterday. It was Athol who encouraged me to head to Joburg and work with Barney Simon. Athol sensed I was a storyteller and believed that Barney was the one to set me on my way. How perceptive he was! I’m forever grateful to our master playwright who showed us all the way.

“Athol Fugard was more than a trailblazer for all of us in this theatre we love so much — he was father, mentor and master. We literally sat at his sandalled feet and listened — mesmerised, grateful for the stories that never ceased. When he left us in those early days and disappeared to that windswept place by the sea [Port Elizabeth] that gave him such inspiration, we understood.

“Athol had gone off to write a play again and we’d all be wiser, richer, when the new offering he’d poured his heart, mind and soul into finally came alive onstage. Athol spoke of sacred spaces — lights fade up … here comes a wonderful story — lights fade down ... to a deeper understanding of who and where we were in this bright, beautiful, sick and tortured land.”

Or turn to the testimony of James Ngcobo, now the artistic director of the Joburg Theatre, on what Fugard meant to him as a young actor and director.

‘He inspired multitudes’

Ngcobo told me, “Athol Fugard hoisted the flag of this country during the madness and anarchy of the apartheid years. He penned stories that gave ordinary, faceless people a pedestal. He inspired multitudes of playwrights, not only in South Africa, but internationally.

“I had an opportunity to direct ‘Master Harold and the Boys’, ‘Boesman and Lena’ at the Market, Baxter and Theatre on the Square, ‘Nongogo’ at Soweto Theatre, Market and Canstage in Toronto. With each of these works, I witnessed how his writing grabbed audiences from the first scene.”

Veteran arts and cultural entrepreneur Ismail Mahomed said, “In his quest for delving into the human experience Athol Fugard’s plays offered hope where there was despair, courage where there was dismay and resilience when all else seemed to be getting lost.

“Thirty years into a new constitutional democracy, Fugard’s ‘Blood Knot’ would be as relevant today as our nation once again grapples with issues of racial privilege and its tensions through scars and unhealed wounds on which salt has in recent weeks been poured by AfriForum and Solidarity.”

Meanwhile, back at the death of another great South African writer, Gibson Kente, The Independent (UK) noted, “If Athol Fugard was the intellectual in South African drama during the dark days before multiracial elections in 1994, ‘Bra Gib’ (Brother Gib) was the popular entertainer. Each inspired opposite ends of the anti-apartheid struggle, but Kente never achieved Fugard’s international fame, principally because he was black and unable to travel abroad.”

Mahomed adds, “In honouring Fugard, I reflect on his play ‘Blood Knot’, simply because Fugard’s work was more than just about imagination and inspiration. His work was a slice of our lives in South Africa. His words on a page knotted together our very existences.”

In the words of Mr M, the lead character in Fugard’s ‘My Children, My Africa’, the playwright had said: “Hope is like a piece of string when you’re drowning; it just isn’t enough to get you out by itself. But it can keep you afloat.” There was much in Fugard’s body of work that could help people keep afloat.

Timeless appeal

Summing up Fugard’s universal, timeless appeal, David Coplan, the author of “In Township Tonight!”, an authoritative history of South African theatre and music, told me the news of Fugard’s death had left him with overwhelming sadness.

He wrote: “South Africa’s greatest playwright as well as theatrical craftsman, Athol Fugard made the comprehension of the apartheid regime’s style of perfidy, turpitude, moral corruption, hypocrisy and almost unspeakable oppression clear and performatively visible on stages and screens throughout the world.

“His sharp-witted, ironic prose crystallised humanity’s issues like no one else’s. He was credibly called the greatest playwright in the English language during his lifetime. Even now, the many regular revivals of his works point the way toward an immortal future for this magnificent treader of the boards.”

Malcolm Purkey, the lead creator of yet another great piece of South African theatre, “Sophiatown”, and a veteran director and drama educator, added to the applause for Fugard’s influence: “Growing up in apartheid South Africa and working in theatre from my early twenties, there was nothing more exhilarating than watching the work of Athol Fugard.”

Great figure that Athol Fugard was, and a guarantee people will be watching productions of his plays for many decades to come, it is a great sadness he will never become a Nobel Literature Prize laureate, as only the living can be nominated for it. Fugard now belongs to the ages and the angels. DM