This should be a book review but because I am impatient and too excitable, it will be a look at the author behind one of Jacana Media's latest titles, The Fragile Mental Health of Strong Women. For better or worse the conversation about mental health has become mainstream, but for black women it is still something that is seen and not addressed.

Michelle Kekana’s debut follows three modern South African women who find themselves brought to breaking point as they navigate the complexities of life, love and mental health. Utterly engrossing from the first page, The Fragile Mental Health of Strong Women is a bold exploration of what it means to be “strong”.

Kekana says she decided to follow three characters because she wanted to emphasise that mental health illnesses manifests differently in different people from all walks of life. The story was important to write because “it’s something that is experienced but not talked about. Mental health is a very taboo topic in black communities, unless you are raving mad or you have schizophrenia or you are stuffing papers into your panties. Anything less than that is just completely ignored.

“If you are experiencing depression, for example, without a perceivable outward cause, then people dismiss it as attention grabbing and attention seeking and ingratitude. It’s like that running joke on Twitter where they say your parent would say how can you be depressed when there is so much meat in the fridge,” Kekana explains as we both laugh at the reference.

In the book one of the characters, in planning a suicide, she thinks about how to make her death as convenient as possible for those around her, such as doing it close to pay day so they can have money for initial preparations. This gives a clear picture of the mental gymnastics it takes to be an adult, and if you are mentally unwell these thought processes and actions can be debilitating and overwhelming.

The book explores themes around mental strength, garnering hope and self-discovery. “It’s worse when you are a woman, I think, because we do a lot of the emotional labour in most households so we are not allowed to crumble, at all. So I was trying to contrast the strength that is expected with the fragility that is experienced in fiction form,” Kekana said.

An excerpt: Making the resolution to end it all fills me with an odd type of peace. My inner turmoil is silenced. A Saturday seems like the most logical day. For one, my mother can have the funeral the following Saturday. This gives her six full days to plan. Funerals in my community are big, expensive undertakings. We slaughter livestock to feed the masses of mourners. Funerals are so expensive they have been known to bankrupt families. Clever blacks like my mother offset the possibility of bankruptcy by having funeral policies that ensure the send-off is elaborate.

The book continues in this style that pulls you into what informs these women, their worlds and contexts. Asked what she hopes people will take away from the book, Kekana says: “I hope the characters breathe for the reader, I hope they don’t sound made up, I hope people see aspects of themselves or people they know. I’ve always thought that good literature is real literature; you want to read a piece of fiction and think, actually that is the truth.”

Although this is her debut book in fiction, Kekana has long been in the literary space. She was a 2021 JIAS Writing Fellow and has contributed to an anthology of essays exploring post-apartheid South Africa. She is a former teacher and considers herself a lifelong learner.

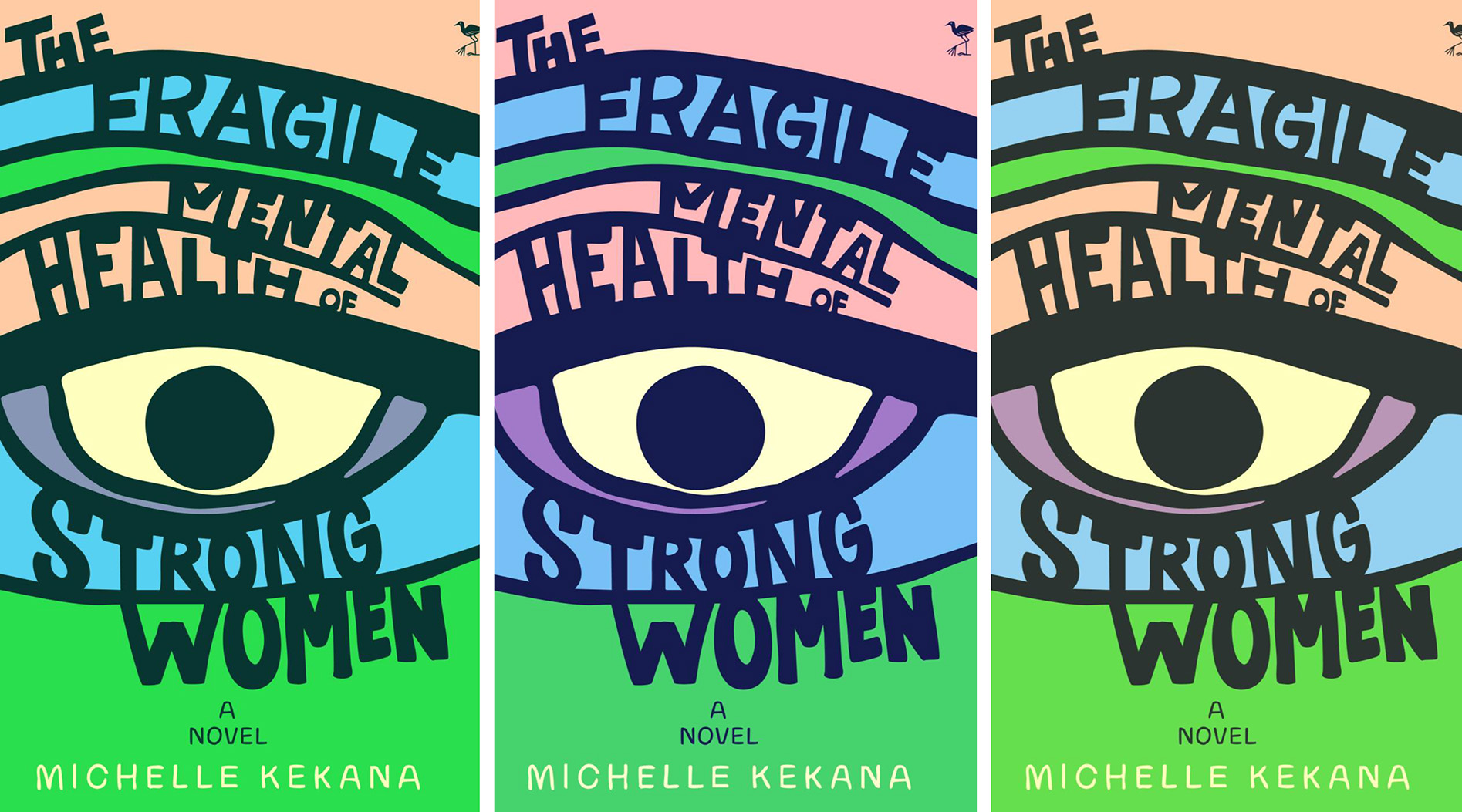

In Michelle Kekana’s debut novel, three modern South African women find themselves brought to breaking point as they navigate the complexities of life, love and mental health. (Photo: Supplied)

In Michelle Kekana’s debut novel, three modern South African women find themselves brought to breaking point as they navigate the complexities of life, love and mental health. (Photo: Supplied)

Beginnings

A passion for writing came from her mother having to take her to work at a very young age because she couldn’t afford creche or daycare.

“My mom was a teacher and would place me at the back of the class, give me crayons and a book and tell me to keep quiet. So because of passive learning, I was picking up words and sounds and it felt like cracking code. In my teens I would sneak out of actual class to be at the library,” Kekana says.

“I have always enjoyed words. I think, in a way, words make a person immortal. Shakespeare died 400 years ago but we still have content of his thoughts, in terms of books.”

Kekana is passionate about bringing to life the stories and ideas she wishes existed. As a devoted mother of four (ages 10 and 25), she balances family and creativity with deep intentionality, which are among the themes in the book.

Asked how she put the book together, she says: “I’m not a great planner, I’m a type B kind of person, so I wrote this book almost exclusively on my phone. A chapter would come as I was peeling potatoes or any mundane task and I would put it down. Sometimes nothing will come for three weeks after that.”

Kekana also approached writing in this manner because she wanted the book to feel like a passion project, not an obligation, and this allowed the book to come to her.

Another excerpt: Lunga keeps quiet for a few minutes after my rant. I feel terrible for shouting at him. Babies cry, I rationalise. They are impatient because they have no sense of time. Lunga is not trying to ruin my life. I cannot assign malice to an infant. I bend down to kiss an apology into his forehead, but he starts wailing, trying to thrust the pacifier out of his mouth.

The book reflects all Kekana’s research and lived experiences in a world she has created, exploring how black women are labelled as strong, with their tears often seen as indulgent and expected to have an imminent expiration date.

“The conversation of depression being idiopathic, without a cause, is also very important. Sometimes people look for trauma or a reason – it could just be like in my case that your brain does not produce enough serotonin so you need medication to assist with that,” she says.

Kekana says these conversations are significant because they can help lessen stigma and shame. This is seen in the book as the characters navigate mental health issues until they have to learn to be kinder to themselves.

“Your inner world is important, how do we relate with ourselves… when you trip and almost fall do you think ‘what a clumsy clutz’ or do you actually say, ‘I’m so sorry, I’m glad you didn’t get hurt’.

“The mind is the protagonist in this story. The thing about depression is that even though it is your mind that is ailing, it also is your mind that has to get you right, it is your mind that has to say, ‘okay, this is too much, me not being able to get out of bed’. It is your mind that will let you ask for help.”

We asked Kekana random questions as we got to know her:

What is your favourite drink?

Water. I know that is boring but that really is my go-to drink. Oh and also Oros, Oros on ice, beautiful! I love it.

What is your favourite book from the past two years?

The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy. I have an unhealthy obsession with the author in general, but I love that even though it is fiction, it is the truth about the human condition.

What do you try to do on the day that is specifically for you, whether it’s small or a ritual?

I don’t have a specific self-care thing I do daily, but I will say I don’t put on masks, I don’t smile when I am not amused, I don’t laugh when I don’t find something funny. I think that is the kind of self-care I need. Putting on a face is exhausting. Being yourself the whole day means there is no need to rest when you get home, you are truly yourself in all spaces. DM

Michelle Kekana’s debut book, three modern South African women find themselves brought to breaking point as they navigate the complexities of life, love and mental health.

(Photo: Supplied)

Michelle Kekana’s debut book, three modern South African women find themselves brought to breaking point as they navigate the complexities of life, love and mental health.

(Photo: Supplied)