A dozen years in the making, The Inheritors weaves together the stories of three ordinary South Africans over five tumultuous decades in a sweeping and exquisite look at what really happens when a country resolves to end white supremacy.

There’s political activist Dipuo, who fought to take down history’s strictest segregationist system; Dipuo’s daughter Malaika, who excels brilliantly after segregation’s collapse but wrestles with her relationship to her mother and her duty to her country; and Christo, one of the last White South Africans drafted to fight for apartheid as it crumbled around him.

In his review of the book for Daily Maverick, David Reiersgord called it “wonderful and thought-provoking” – a “remarkable achievement”.

Observing subtle truths about race and power that extend well beyond national borders, Fairbanks explores questions that preoccupy so many of us today: How can we let go of our pasts, as individuals and as countries? How should historical debts be paid? And how can a person live an honourable life in a society they no longer recognise?

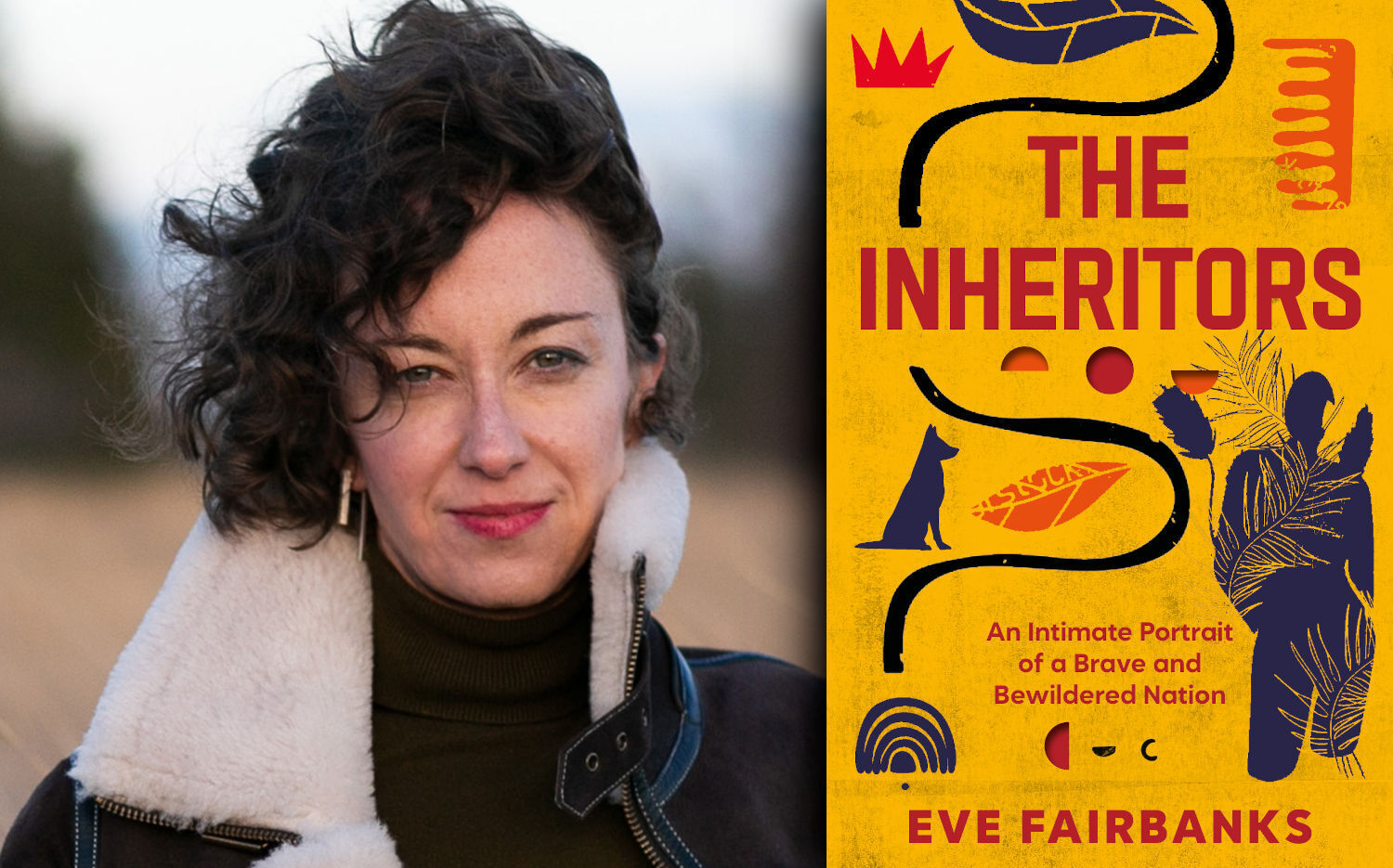

Born in Washington, DC, in the US and raised in Virginia, Fairbanks has lived in Johannesburg for 13 years. She has been published in The Washington Post, The New York Times and The Guardian, among others. The Inheritors is her first book. Read the excerpt.

***

One of the first books I read in South Africa was written by a former anti-apartheid activist. She confessed she missed apartheid: it rendered every choice you made, as a white person, meaningful and potentially heroic – from the race of the people you dated to the books you read. Another anti-apartheid white journalist lamented that there was “no [clear] moral place” for a white person to “stand any longer” without apartheid’s extreme manifestation of evil.

Believing a grotesque enemy still exists within your own community could be clarifying. I think some of that motive drove European and American foreign correspondents to Orania, the all-white town. It had negligible news value. But it gave them something to recoil from morally – and, thus, to feel more secure about where they stood on the spectrum of white people’s behaviour.

Foreign white people were always situating themselves on the white-people spectrum by locating unreconstructed Afrikaners at the reassuringly bad end of it. That put them in the pretty good middle. Often, American acquaintances of mine brought up news stories about South Africa: in particular, ones that implied the country was failing solely because of white intransigence. I remember receiving multiple copies by e-mail of a story in a British tabloid that claimed tens of thousands of Afrikaners were teaching five-year-old children how to kill black people at a secret shooting range.

It reminded me of a time, not long after I got to South Africa, I went to visit a farmer named André. I’d read about him in a newspaper. Under apartheid, he’d supported the white regime. But then he changed his mind.

After apartheid ended, he started a program to mentor black farmers, who hadn’t previously been allowed to own large commercial farms. He got his farmers’ union to sign on. Before dawn, they would drive to their black neighbors’ houses to put themselves at their service. André’s neighbor, Moses, who grew up poor in a segregated area, wanted help setting up a digitized accounting system, so André helped him.

It was a feel-good story. “We’re all people,” André said he had realized. “We sink or swim together, now I see.”

After I got into my car to leave his farmers’ union building, though, I heard a tap at the driver’s side window. It was André. I rolled the window down.

“Can I ask you a question?” he said, poking his head in. “As a journalist, you travel around. So. Our young people. Do you think they’re even more racist than we were?”

“What do you mean?” I asked, taken aback. “My son,” he said. “To be honest, I’m doing this for my son. He’s sixteen. I want him to be able to take over our farm. If our black neighbors go down, we all go down.”

But André was distressed by something he was observing in his son. He said his son lashed out bitterly about the new dispensation, even calling black people by a derogatory term André wouldn’t have used under apartheid.

Visit Daily Maverick's home page for more news, analysis and investigations

This wasn’t supposed to be happening. It was supposed to be older white South Africans who might remain stuck in the past. It seemed to André, though, that other, queer, frightening changes were occurring. “I’m afraid for my son,” he told me through the window. He lowered his voice. “I’m afraid of my son.”

The thing is, I didn’t think the “tens of thousands” part of the British tabloid story about five-year-old white children learning to shoot black people was remotely true. And, in retrospect, I’m not even sure what André said was true, either. André’s worry had sold itself as sincere concern. And, to André, I believe it felt that way.

But like so much of what I heard in South Africa – such an unexpectedly wide range of opinions and emotions – it ultimately absolved the speaker. If Andre’s son became racist no matter what André taught him, then that proved this instinct lies deep in human nature and can’t be eradicated. And so it wouldn’t be André’s fault that he hadn’t eradicated it in himself when he was young – nor, perhaps, that he hadn’t fully done so even now.

Fixating on extremists makes holding the fort – as morally ambiguous as your day-to-day life might be – a quietly heroic act. To be white in South Africa still recruits a person into constant unsubtle and subtle acts of cruelty and racial bias, whether it’s underpaying your domestic helper – even if you triple your neighbors’ pay rate, it’s still a pittance – or cruising past the half-dozen beggars you see on a ten-minute drive to the grocery shop. There is little practical way to help all of these people, or the tens of thousands whose shacks you see from many office buildings. There isn’t a way to dismantle systemic racism with your own hands. And so it was worth it for some people to keep Christo around – even to inflate his power. To believe that vicious varieties of white supremacy are reemerging paradoxically afforded white progressives a sense of comfort about where they ethically stood. DM/ ML

The Inheritors by Eve Fairbanks is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers (R320). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!