This year marks the 46th anniversary of the death of Bantu Stephen Biko, and it seems he is fast fading from the country’s memory.

I have often written of the importance of history and memory, not only as a marker of our evolution, but also as a means of learning, accountability and informing a future we can all aspire to.

This has never been more urgent than in the wake of the death of IFP president emeritus Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi and how he is being remembered.

Steve Biko in 1977. (Photo: Gallo Images / Daily Dispatch)

Steve Biko in 1977. (Photo: Gallo Images / Daily Dispatch)

It seems to me that the commemoration of Biko’s death has been traded in for a revisionist and dishonest posturing of commemorating Buthelezi. For those who do not know, have forgotten or choose to forget, it is necessary that we examine these separate but intersecting legacies.

Being born in the early 1980s means I am acutely aware of the events that unfolded in the 1970s through first-hand accounts, and even more so in the 1990s as lived experiences, and I will never tire of speaking of them.

While studying medicine at the University of Natal, Biko founded the Black Consciousness Movement in the mid-1960s during the leadership vacuum that was left after the arrest of ANC and PAC leaders following the Sharpeville Massacre. He understood that part of the colonial and apartheid project’s endeavour was to psychologically inculcate a sense of black inferiority to whiteness and conversely white superiority to blackness.

As Biko said: “At the heart of this thinking is the realisation by the blacks that the most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

Biko led the Black Consciousness Movement with Barney Pityana who was quoted at a lecture during the National Arts Festival in 2007 as saying of Biko’s character that most important was his “humanity, a level of inherent trust in our people to cure, the possibility to think beyond what confines, and the possibility of humanity” and said that black consciousness “produced a cadre not bound by finance and structures, and pushing the bounds of possibility”. Pityana is himself a respected academic and human rights lawyer and to this day none has contradicted Biko’s moral character and dedication to the liberation of black people.

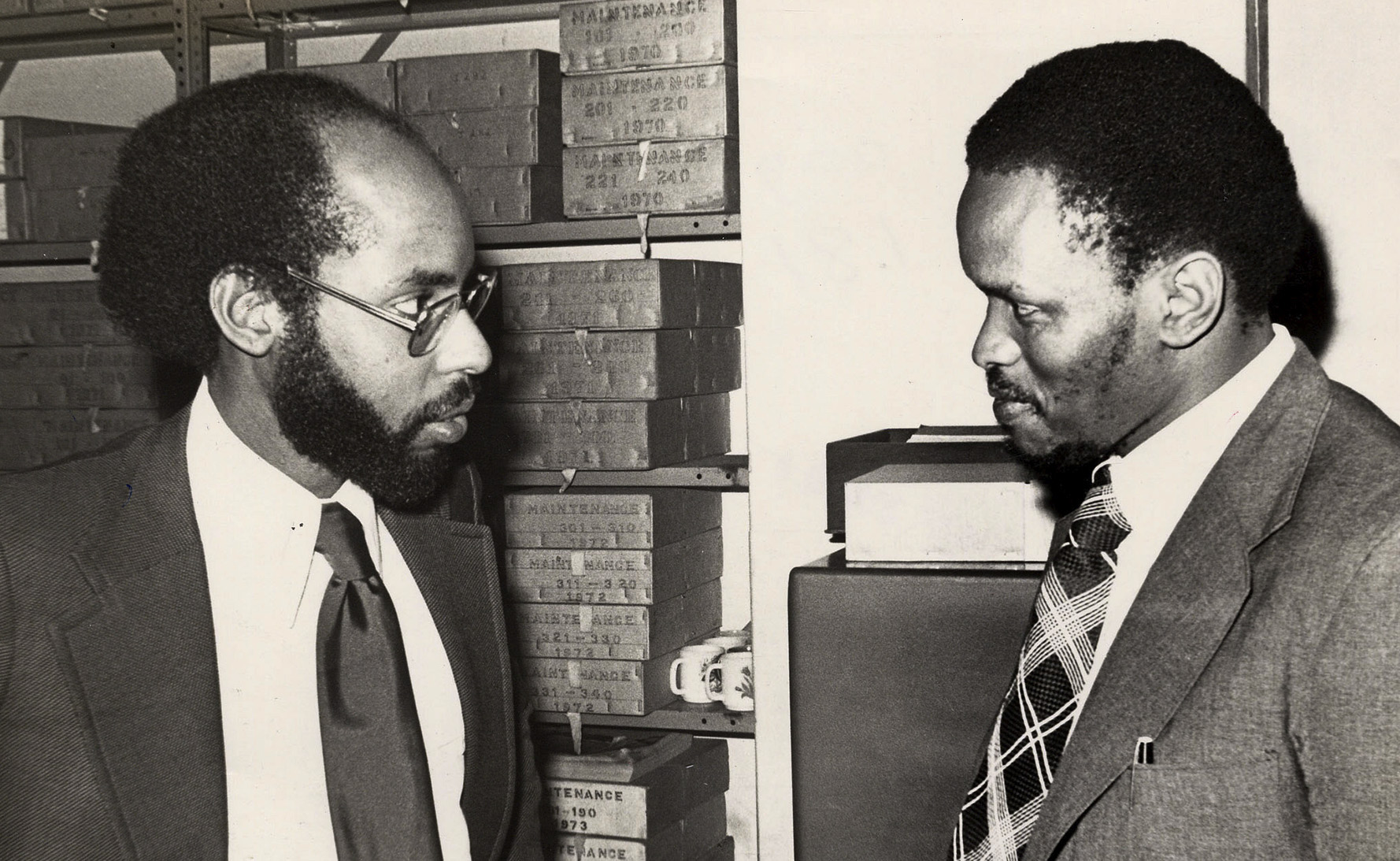

Steve Biko with US embassy official Richard Baltimore after Biko was charged with subornation to perjury. Circa 1970s. (Photo: Gallo Images / Daily Dispatch)

Steve Biko with US embassy official Richard Baltimore after Biko was charged with subornation to perjury. Circa 1970s. (Photo: Gallo Images / Daily Dispatch)

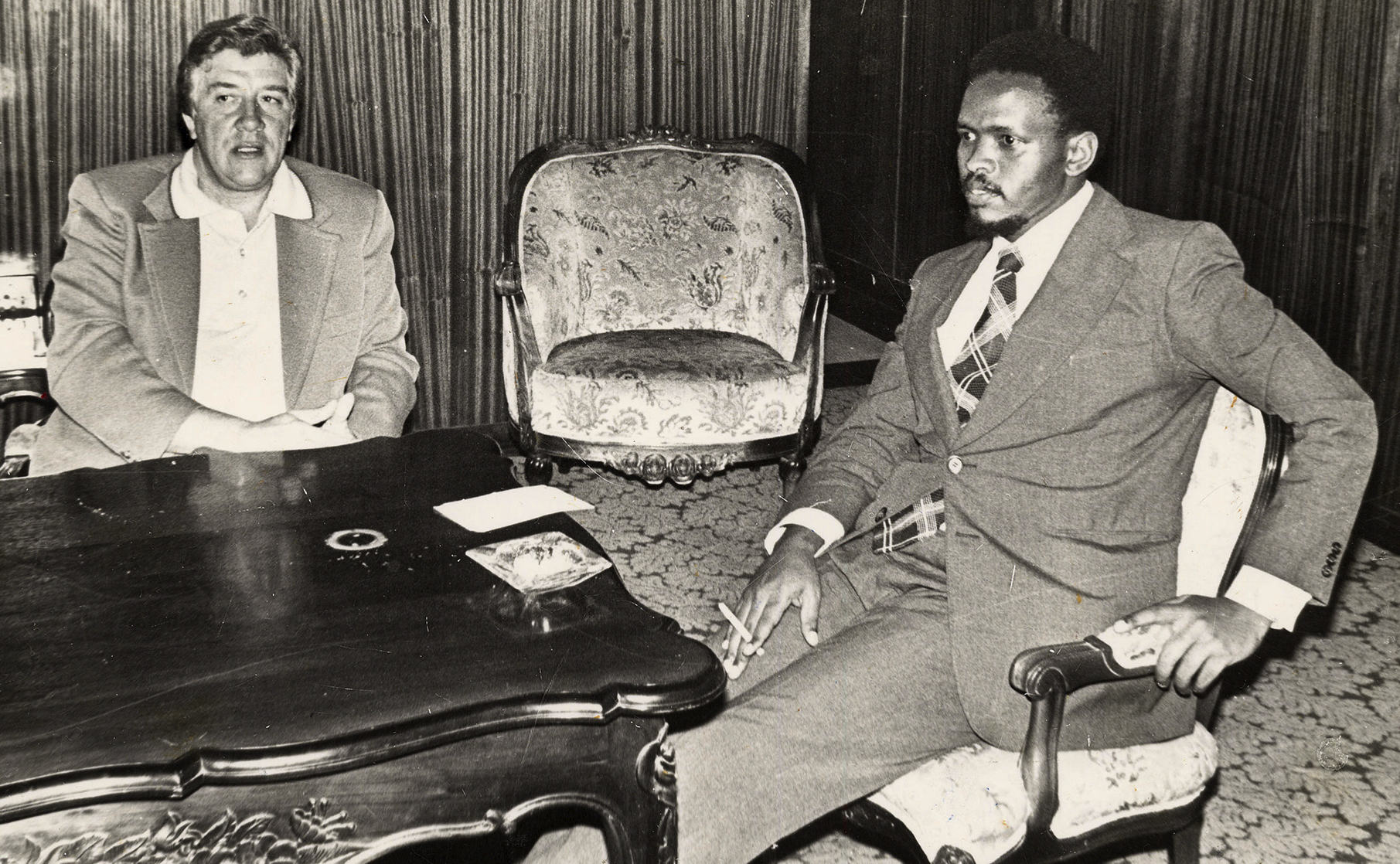

Steve Biko with US senator Dick Clarke, chairperson of the senate subcommittee on Africa, who flew from Lesotho to East London to meet Biko. (Photo: Gallo Images / Daily Dispatch)

Steve Biko with US senator Dick Clarke, chairperson of the senate subcommittee on Africa, who flew from Lesotho to East London to meet Biko. (Photo: Gallo Images / Daily Dispatch)

Buthelezi achieved academic success at the historic University of Fort Hare which is known to have produced some of the most progressive black political minds who contributed to South Africa’s liberation struggle. Among them are Oliver Tambo, Nelson Mandela, Robert Sobukwe, Barney Pityana, Chris Hani and Govan Mbeki.

Interestingly it was during his time at Fort Hare that Buthelezi joined the ANC Youth League. However, soon after graduation he started work at the department of Bantu administration, first as a clerk before rising up the ranks to chief executive officer of the Zululand Territorial Authority. This is when he started to drift away from the ANC’s political ideology as his continued position as a “bantustan homeland leader” was dependent on the apartheid government’s continued existence. In 1975 he formed the National Cultural Liberation Movement, Inkatha Yenkululeko yeSizwe which subsequently became the Inkatha Freedom Party, and in 1976 he became the chief minister of the KwaZulu government.

Today, people’s memory of Biko and his real contribution fades while Buthelezi has been hailed as a ‘nation builder’ and a ‘complex’ leader, whatever that means to the families of those who were butchered.

Biko was a vehement opposer of “bantustan homelands” and made it his mission to resist the illegitimate system, describing them as “the greatest single fraud ever invented by white politicians”. Characterised by repressive violence by the apartheid government over black people, any black person associated with the bantustans was seen as a corroborator and dissenter against the plight of the oppressed.

He therefore sought to liberate black people and it was because of his ideology, which threatened to derail the apartheid system, that in August 1977 he was arrested and the following month died in police detention. His heroic ideology lived on through the struggle to liberate South Africa and usher in a democratic system not based on oppression.

Brutal slaughter of thousands

In the early 1990s, as South Africa’s oppressive system was on the brink of defeat by liberation movement efforts, a counterforce in the form of the IFP, led by Buthelezi, collaborated with the apartheid government in the brutal slaughter of thousands of black people. This was in part driven by Zulu nationalism and Buthelezi’s determination to continue to enjoy the spoils of being a Bantustan leader installed by the government.

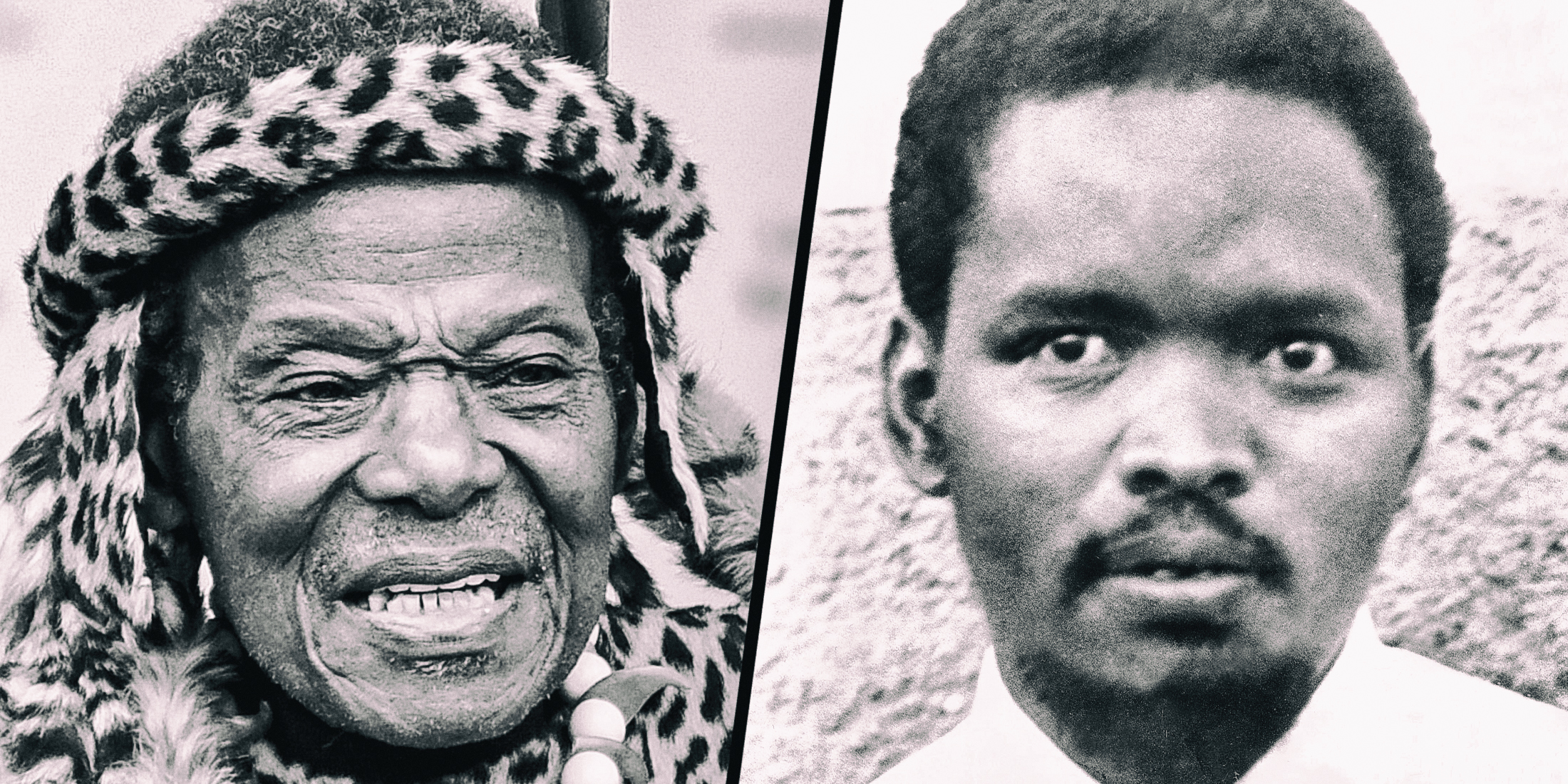

Gatsha Mangosuthu Buthelezi at a PFP meeting. (Photo: Wessel Oosthuizen / Gallo Images)

Gatsha Mangosuthu Buthelezi at a PFP meeting. (Photo: Wessel Oosthuizen / Gallo Images)

Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi addresses the media at Durban Manor on 15 October 2021. The IFP founder reportedly deliberated on the baseless and unwarranted attacks emanating from the ANC in KwaZulu-Natal and other pressing matters. (Photo: Gallo Images / Darren Stewart)

Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi addresses the media at Durban Manor on 15 October 2021. The IFP founder reportedly deliberated on the baseless and unwarranted attacks emanating from the ANC in KwaZulu-Natal and other pressing matters. (Photo: Gallo Images / Darren Stewart)

My memory of that time is that of hearing about people being butchered with pangas on trains, having nowhere to run, with some resorting to jumping off to their deaths. I remember the fear that gripped the East Rand township of Boipatong as people were burnt and massacred by IFP supporters. People were displaced and families remain broken as a result of Buthelezi’s legacy.

In a stinging yet necessary article, City Press editor-in-chief Mondli Makahnya says: “Buthelezi never acknowledged his role in propping up apartheid through violent means and his role in the slaughter of innocents. He spent his last years trying to convince the world that he had always been a man of peace, right up there with Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi.”

Whereas Biko never lived to see his 31st birthday, Buthelezi lived to the ripe old age of 95, with the blood of thousands on his hands. He lived long enough to refashion himself as a supporter of democracy and a seemingly sage elder statesman.

Today, people’s memory of Biko and his real contribution fades while Buthelezi has been hailed as a “nation builder” and a “complex” leader, whatever that means to the families of those who were butchered.

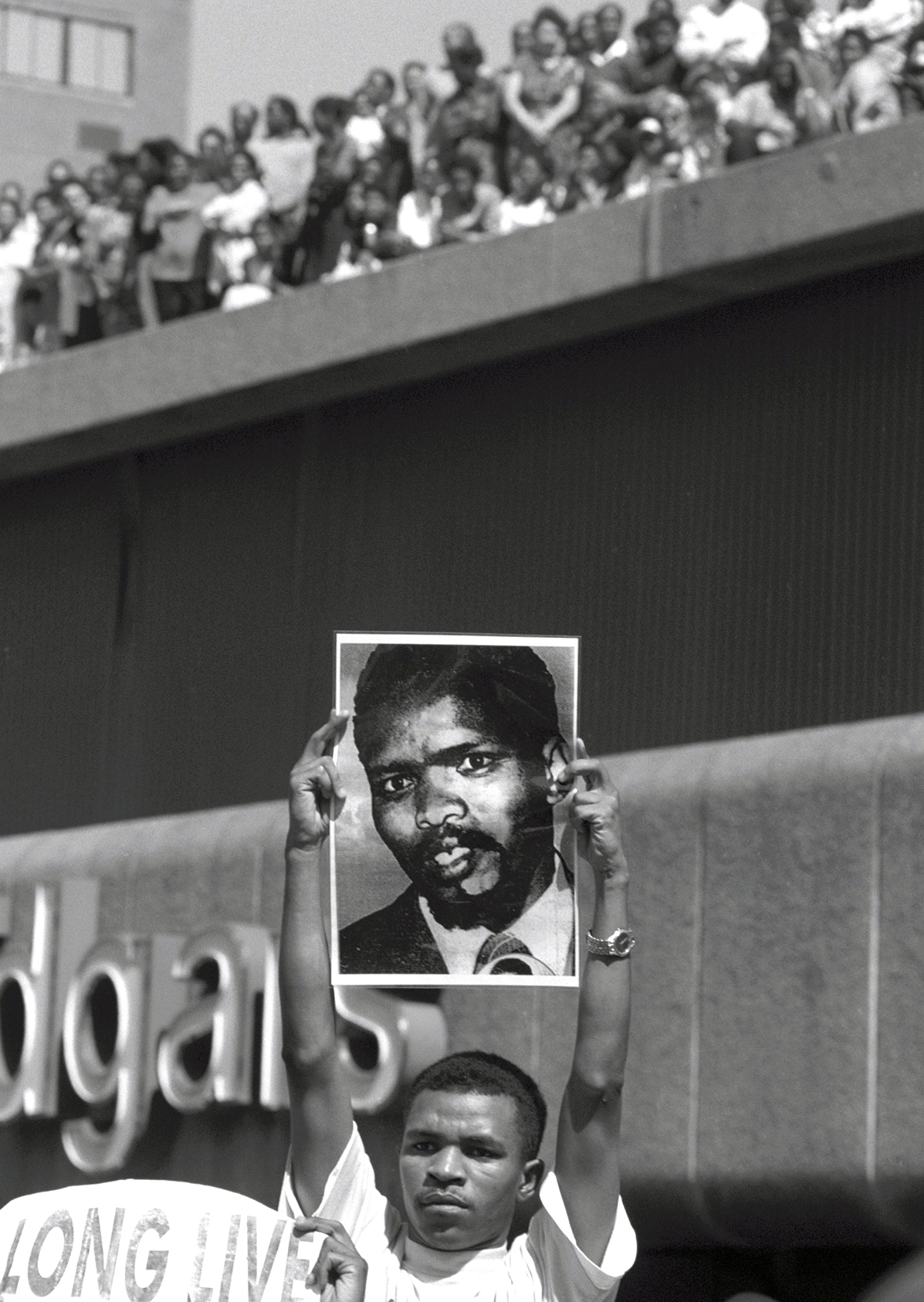

A picketer holds a poster of Steve Biko during a demonstration on Oxford Street, London, during TRC hearings in East London in 1996. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oryx Media Archive)

A picketer holds a poster of Steve Biko during a demonstration on Oxford Street, London, during TRC hearings in East London in 1996. (Photo: Gallo Images / Oryx Media Archive)

The funeral of the massacred. The site of the infamous Boipatong massacre on 17 June 1992, when 46 township residents were killed by local hostel dwellers. This happened at a time when negotiations towards the end of apartheid in South Africa were in progress. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media 24)

The funeral of the massacred. The site of the infamous Boipatong massacre on 17 June 1992, when 46 township residents were killed by local hostel dwellers. This happened at a time when negotiations towards the end of apartheid in South Africa were in progress. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media 24)

Biko dared to dream of a future where all black people were free from oppression and violence and instead found value in themselves. While Buthelezi led a separatist and tribalist agenda that turned people against each other.

So, as we look back on our heritage as South Africans and the legacies of these two men, we will find that it may be more prudent to follow the principled and humanity-based values espoused by Biko. Buthelezi’s legacy is, however, not to be relegated to the dustbin of history but instead to be examined as a cautionary tale of the dangers of pursuing singular nationalist interests as a means of rising to power.

An honest account of history will not be kind to Buthelezi, but an honest account of history will show that we owe Biko our freedom. DM

5 June 1992. The funeral of the massacared. The site of the infamous Boipatong massacre on 17 June 1992, when 46 township residents were massacred by local hostel-dwellers. This happened at a time when negotiations towards the end of Apartheid in South Africa were in progress.

(Photo: Gallo Images / Media 24)

5 June 1992. The funeral of the massacared. The site of the infamous Boipatong massacre on 17 June 1992, when 46 township residents were massacred by local hostel-dwellers. This happened at a time when negotiations towards the end of Apartheid in South Africa were in progress.

(Photo: Gallo Images / Media 24)