In 1973, English rock band, The Who, released a “rock opera” on a seminal double album called Quadrophenia. Its opening track is titled The Real Me and has the desperate refrain of a youngster to his mother, “can you see the real me?”

The album was The Who’s contribution to a teenage rampage then making itself felt across music; an irruption from a new generation of young people pissed off with grayness and excited by the power of sound, colour, rebellion and the arrival of genuinely benign technologies that suddenly seemed to add an extra dimension to living (a bit like now without the benignness). The meaning and moods of the songs that seemed to come mysteriously off the vinyl were enhanced by album covers that were works of art and imagination. Back then the look and feel of an album was as important as the sounds that would explode from within it.

Buying a record was a total experience.

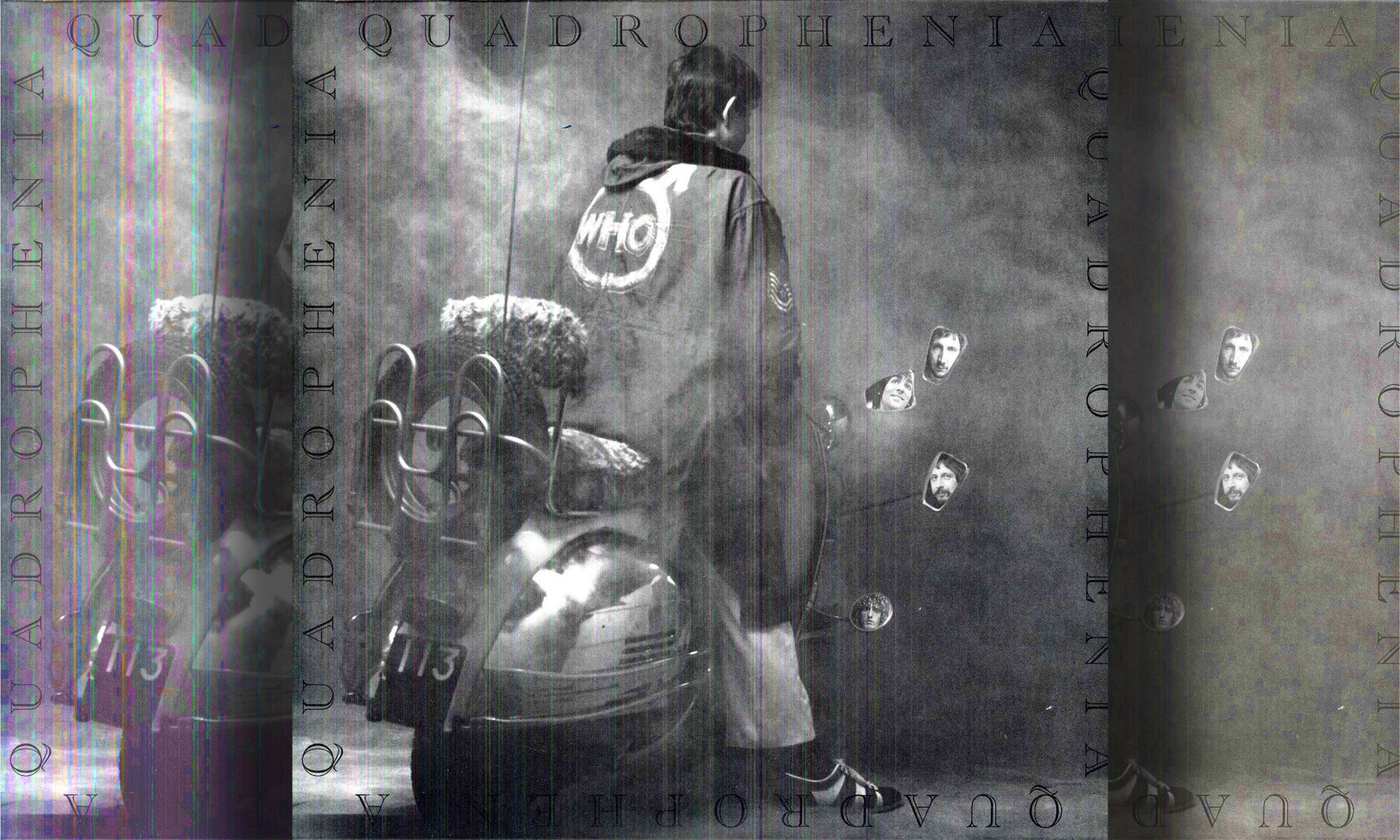

But unlike a Bowie, Beatles or Pink Floyd album, Quadrophenia’s sleeve was grey, dour and dark. Its front cover is a photograph of a Mod, uniformed with parka and Vespa, his back to the camera, staring out into the distance. Mods were part of a subculture of working-class youth and this album represented what we might call the genre of musical realism, embracing alienation rather than denying it.

Such was its power that the music on the two LPs inside Quadrophenia’s haunting soundtrack have stayed with me since I first played it on a tape recorder in the mid-1970s.

Something was planted inside me from listening to those songs of disaffection and rejection in a cellar at my boarding school.

Its opening track, I am the Sea, announces the album’s dark side with a horn melody, drifting over the waves like the sound of a distant foghorn, riffing with the swells of a perpetually restless sea. The cry “can you see the real me” is carried across the waves before the opening crash of Keith Moon’s furious drums launches a series of songs expressing youth alienation, anger, rebellion and defeat. It was bleak but beautiful, simultaneously local and existential. It spoke to teenage angst during a time of political and social transition.

Those words, that melancholy, has run through my blood ever since.

Six years later, in 1979, Quadrophenia the album was followed by Quadrophenia the film, with its screenplay implanting on the music a more explicit narrative about youth culture and alienation, culminating in a battle between working-class gangs of Mods and Rockers in the Southern coastal town of Brighton in England circa 1960. The film’s denouement comes when Jimmy, its lead character, drives his idol’s Vespa scooter off the top of the abrupt chalk cliffs of Beachy Head on the South Downs.

A moment of modern tragedy as definitive as the suicide of Othello.

‘Oh I do like to be beside the seaside’

Quadrophenia is just one of the many layers of memory and meaning that have accreted around Brighton, a seaside town on England’s South coast, over time. As a youngster I was aware of Brighton as a centuries-old seaside resort, and the place where the IRA planted a bomb that nearly succeeded in killing Margaret Thatcher in 1984.

In real life I visited Brighton only once, somewhere in the mid-1980s, to attend a conference of the Labour Party Young Socialists, then controlled by Labour’s Militant Tendency. I stayed in one of the now tawdry B&Bs that clutter the edge of the famous seafront Parade, looking out onto the West Pier; once glorious and bold in its architecture, now just a metal carapace marking time.

I’m writing this essay because a recent visit to Brighton (on my way to give a talk at the London School of Economics Inequality Institute) revived these threads and thoughts in a surprising way.

I spent a few days staying with Robin Gorna, a friend and veteran Aids activist, at her home in East Dean, a village about 10 miles from Brighton. East Dean hails back to the 13th century. It is situated in the middle of the South Wolds National Park, where the public has been given freedom of the hills even though the land is still farmed and privately owned.

It was going to be a quick visit to an area I didn’t know. So, I hadn’t planned on doing any running. But the beauty of the surroundings, the deep green of the English countryside in June, drew me onto the downs, hills whose contours guided me onto the Seven Sisters Cliffs and to the precipitous sea’s edge.

For me, running is almost always a release. But every now and again, it can be a catalyst to an out-of-body experience. The joy of running happens when your body stops transmitting to your mind its complaints about the hard physical labour of rapid movement and instead feels lifted by your spirit. Wings on your heels replace lead in your thighs. It’s all in the head.

Finding myself on the edge of the high chalk cliffs, with nothing but seagulls, cows and sheep for company, lifted me out of myself. This was a point of convergence of the senses: sea, sky, cloud, cliff, land, wind, green fields and little me. It transferred to me a physical and mental energy that hadn’t been there when I’d pulled my running shoes on an hour earlier.

Love Reign O’er Me

In my state of endorphin-induced euphoria, those songs and their lyrics from Quadrophenia were drawn from recesses of memory. They became the soundtrack to my run, blending with and shaping my feelings, making thought crystals.

From the top of Flagstaff Brow I set my sights on Beachy Head. My path took me through the Birling Gap, a cluster of houses, cafe and walkway down to the beach, and past the Belle Tout Lighthouse (“one of the few lighthouses in the world where you can now stay Bed and Breakfast”).

After half an hour’s flight I reached Beachy Head. Standing on top of the cliffs, buffeted by a wind coming off the sea, I stumbled across a granite memorial to members of the Royal Air Force who, during World War 2, took off from this corner of “forever England” on bombing missions to Germany. The memorial looked lonely and faded. It recorded that: “For many Beachy Head would have been their last sight of England.

“55,573 gave their lives in the cause of Freedom.”

Royal Air Force Memorial at Beachy Head (Photo: Mark Heywood)

Royal Air Force Memorial at Beachy Head (Photo: Mark Heywood)

That’s a lot of people and as I stood there I imagined those unknown (to me) soldiers and their loss.

But unfortunately, on that blustery afternoon, with blue skies and a view to die for out over the English Channel, it was hard to feel anything other than futility in their sacrifice. I have had the same feeling on the top of Spion Kop, the site of a famous battle between the Boers and the British at the turn of the 20th century, as you look across to the beauty of the Drakensberg mountains.

To me, all that lost life just feels like a waste, a culling of the young to advance the deceits of a class of elites, who when they run into conflict with each other make another class bear the sacrifice. “Just as they are preparing to do again,” I thought to myself, as today’s elites concoct new wars against Russia and China; or seed but then stand aside from wars and genocide in other parts of the globe.

I guess our contemporary state of burgeoning war is why these thoughts came to mind. Bob Dylan sang it best: “Damn you masters of war.” Sex Pistol Johnny Rotten, put it more bluntly: “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?”

Nature’s symphonies

But on a smaller scale these cliffs, the land’s end, were also saying something else. I was aware that writer Nick Cave’s 15-year-old son Arthur fell to his death somewhere along the route I ran. They felt to me like the frontier for the wars that go on within ourselves, our battles with loneliness, addiction, experimentation with mind-altering substances and quest for identity and meaning. The cliffs’ have a power that flows out of their ancient geology: they are a place where the endless roar of tortured thoughts can be matched, but not quelled, by the endless symphonies of wind and crashing waves.

This place where the land ends is a place of joy and defeat, life and its fuckeries, what Cave calls the “fucked-up cosmic mischief”, which can intrude to remind us that there’s only a terribly thin line that separates living and dying, security and tragedy, happiness and loneliness, even at the best of times. Our fragility and cosmic insignificance. Humans break things with gay abandon. But we too can be broken.

Maybe that’s how these cliffs acquire a mesmeric force that draws people here to create art… and to commit suicide. Indeed, just that morning Robin had told me that Beachy Head is one on the most popular suicide destinations in Europe.

A popular place for doing some dying.

After my encounter with the granite war requiem my spirit guide brought me to a second monument. This time the stone plinth was much smaller, almost hidden in the grass. I presumed its deference to be deliberate; it sought to be unobtrusive and deferential in daring to offer a last counsel to those thinking of ending their lives. Its small plaque starts with a biblical injunction:

Mightier

Than the thunders

Of many waters

Mightier

than the Waves

Of the Sea

The Lord on High is

Mighty

Psalm 92:4

Before adding:

God is always greater

Than all of our troubles

Last post to the anguished. (Photo: Mark Heywood)

Last post to the anguished. (Photo: Mark Heywood)

Nearby a bunch of fading flowers had been tied to the stump of a signpost, perhaps a memorial to someone who didn’t get the memo or believe.

Too late: In memory of somebody’s somebody. (Photo: Mark Heywood)

Too late: In memory of somebody’s somebody. (Photo: Mark Heywood)

Zen Buddhism likes to remind us that “we are more than our thoughts”. Quite right. In the midst of our rage of feeling there is a constant: insentient life, the swell of the sea, sometimes becalmed, sometimes angry, ever gnawing away at the base of the cliffs, slowly cutting them down to size. (Such is the force of the sea, I was told by a helpful volunteer lady at the cafe at the Birling Gap, that the coastline has been eroded by several hundred metres in the past 100 years. “Wait to see what happens when the seas rise because of climate change,” I thought. But she won’t be around then and neither will I.)

Brighton’s Rock

That might have been the end of this stream of connection. However, just before I left Brighton, Robin gifted me a copy of Graham Green’s classic novel, Brighton Rock which, despite its “classic” status and my being a student of English literature, I had never read.

The novel was written in 1938, coincidentally another time of transition into social breakdown and war. It is a bleak, beautiful depiction of the life and thoughts of a small-town Brighton gangster, Pinkie; Rose, the innocent ignorant working-class girl he entraps in marriage as a way to silence her from ratting on him for the murder of Fred Hale; and the larger-than-life drunkard come amateur detective, Ida Arnold, who manages to unravel the murder of Hale, a man she never knew, but who kissed her distractedly in the back of a taxi, his eyes on the killers in the car behind him.

Aside from being a celebrated crime story and morality tale, Brighton Rock is a tale of the two towns in one Brighton. The hotels and townhouses of the glitzy, pretentious, faux bourgeois Parade that looks out onto the sea versus the dark city and damaged people who are hidden – and hide – behind its bright lights.

It’s the tale of every tourist town.

Pinkie thinks of the area behind the Old Steyne, one of Brighton’s attractions, as “the shabby secret behind the bright corsage, the deformed breast”. He associates it with the extreme poverty of his childhood, an “obscure shame as if it were his native streets which had the right to forgive and not he to reproach them with the dreary and dingy past”.

Observing children at play in broken streets and dilapidated houses “took his mind back and he hated them for it; it was like the dreadful appeal of innocence, but there was not innocence; you had to go back a long way further before you got to innocence; innocence was a slobbering mouth; a toothless gum pulling at the teats; perhaps not even that; innocence was the ugly cry of birth.”

Something distinctly Beckettian here.

Brighton Rock and Quadrophenia felt eerily connected to me. But on the basis of a quick Google search I could find no evidence that Quadrophenia is influenced by the novel. Still I’d hazard a bet that Pete Townshend, its composer, must have read it. The rock opera seems to draw from the novel the moods of Brighton, the restless, unceasing swell and retreat of the sea, the darkness and light. As importantly, although their storylines differ, Quadrophenia and Brighton Rock are both depictions of disaffected youth, the alienation of the young people trapped in England’s infamous cradle to grave inequalities of class.

Film and book both end with the deaths of their tragic heroes, falling from the cliffs above Beachy Head.

Film and book are both about children of working-class people grappling to find an identity in a culture that didn’t see them or allow them to dream. They are about identity-denied long before the notion of “identity politics” came along; they ask probing and painful existential questions about “the real me”, life’s meaning and purpose; questions that, dare I say, may be a level deeper and more intractable than those based on sex, race, gender or ethnic origin (important as these signifiers of oppression and discrimination are). They come out of a time when identity could be forged (including through forming a rock ‘n roll band) but rarely faked, as it is today through social media.

“Can you see the real me,” Jimmy pleads to his mother. I used to ask my mother the same question. Her response:

“… I know how it feels, son

‘Cause it runs in the family.”

Like Jimmy, Pinkie is also tortured by insecurity and a thwarted desire to be somebody. His “awful resentment” of society is like a terminal disease, driving him into the easy certainty of hate; he is too scared of the world to entertain the possibility of love even when it briefly stirs within him because that requires a reconciliation with the present; he is haunted by the intimacy of sex because he associates it with his parents’ vulgar weekly coupling in the bedroom opposite his in their too-small house:

“ … he wasn’t made for peace, he couldn’t believe in it. Heaven was a word; hell was something he could trust. A brain was only capable of what it could conceive, and it couldn’t conceive what it had never experienced; his cells were formed of the cement of the school-playground, the dead fire and the dying man in the St Pancras waiting room, his bed at Frank’s and his parents’ bed. An awful resentment stirred in him – why shouldn’t he have had his chance like all the rest, seen his glimpse of heaven if it was only a crack between Brighton walls…”

After killing Fred Hale and then one of his own gang he tells himself, “It’s no good stopping now. We got to go on”, making him like a suburban Macbeth, a yob (that class-laden term of disparagement once in common use against English youth) “in blood/ stepped in so far that, should I wade no more, returning were as tedious as go o’er”.

Except there’s no tragic hero status or redemption for Pinkie Brown. He never had a shot at goodness or greatness, he’s just a hateful, irredeemably damaged small-town hood.

Last thoughts

“And what’s the moral of this?” you might be asking yourself.

As with all literature, there is so much in these stories and songs of Brighton, so powerfully told, that speaks to our present condition. In particular, they remind me for how many generations, class inequality has blighted the lives of those denied equal dignity and opportunity. It didn’t end after Quadrophenia. In fact, little did we know but in the 1970s class inequality was just getting a new lease of life with Thatcher leading the elite charge to a neoliberal world. So it’s not surprising that the same characters are remodelled throughout literature. Two recent Booker Prize winners come to mind: Pinkie reincarnated as some of the young thugs who terrorise the council estates of Glasgow in Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain, or as some of the young soldiers of hate who man barricades in Dublin in the descent to fascism and civil war depicted in Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song.

Read more: Shuggie and Agnes Bain — two newborns on the pantheon of the great characters of world literature

Read more: A review of the 2023 winner of the Booker Prize, ‘Prophet Song’

But inequality tells a much larger tale than just that of blighted lives kept mostly out of polite company. While the cliffs of Beachy Head have maintained their eternal guard, the humans who visit them come from a society that has continued apace in its self-destruction. Since the days when I was a youth listening to The Who at the end of the post-war boom, inequality has metastasised again, thanks in no small part to the political and economic forces unleashed by Thatcher, who, as we know, didn’t die that day in Brighton.

I realise now that part of what was overwhelming me that day on the clifftops was these sirens of inequality. My privilege to be healthy, well-educated and alive, to be able to feel and summon up a life of mostly joy, versus those who will never stand atop Beachy Head, or any similar place of outstanding natural beauty, and feel able to transcend your body and fuse with the elements, calling upon history, music and culture to form the thoughts that capture the moment.

Inequality is not a victimless crime. It is hurting someone, somewhere, with every passing moment. It is damaging psyches, has fuelled anger and hatred, that has created a seam of violence and violent people in all our societies. One wonders, how many of the people who today fill prisons worldwide owe their violence and criminality to the smouldering resentments we witnessed in Pinkie.

At the end of the day, the question we should ask ourselves is not so much “Can you see the real me?” as “Can you see the real we?” The “we” are the societies that harm the “me”.

So my last thought on the clifftops as these strands of being and expression came together was one that I have often had: it is that music and literature remain keys to understanding the subterranean currents that flow under the surface of human society. We would do far better to seek wisdom and remedy from the arts than from sociopathic politicians and their praise singers.

Brighton, Brighton Rock and Quadrophenia, Jimmy, Pinkie and Ida, the exuberance I felt on the clifftops over three days of running, became testament to the fact that politics and government have still solved none of the underlying causes of human pain, alienation, anger and violence that have become characteristic of modern human society.

And probably never will.

We have to look elsewhere, and it starts in ourselves. DM

Too late: In memory of somebody’s somebody. (Photo: Mark Heywood)

Too late: In memory of somebody’s somebody. (Photo: Mark Heywood)