When music legend Johnny Clegg sang and spoke isiZulu he came alive.

He was possessed by a distinct energy which animated his conversation and which was often lacking when he gave interviews in English.

When Johnny spoke Zulu – or when Zulu spoke Johnny rather – there was a playfulness and presence which English didn’t seem to provide.

Zulu enabled the musician and legend to find a path to his soul, his heart, his creativity, his place in the world.

There are languages which allow this playfulness.

English, of course, is pliable, but must be radically bent and tickled and reshaped to allow a sort of informality some other languages offer more readily. Nigerians have stretched English, as have the Irish and the Americans.

The Queen’s English is as much of an emotional and social straitjacket as Algemeen Beskaafde Afrikaans (Generally Civilised Afrikaans) – it keeps all people and things in their place.

Two tongues

There are two versions of Afrikaans in conversation with itself. Always have been.

There is the “generally civilised” version which in 20 years established itself as a full-fledged and internationally recognised literary and academic language.

En route it became the language of officialdom, power, control and white Baaskap (supremacy). It was one of only two official languages in apartheid South Africa and was a compulsory subject in schools.

That is how it landed in my mouth and worked its way to the arsenal of languages that surrounded me.

The push of Afrikaans onto a multilingual black populace led to the rebellion in Soweto in 1976. More than 100 children were shot resisting the imposition.

It was this Afrikaans that was resisted.

Then there is the Afrikaans that has pushed back and smashed the claustrophobic window on the universe a narrow Afrikaans offered.

And it is this Afrikaans which opens up a pathway to a sort of a unique verbal jazz, a flexible code with ready access to humour, satire and ridicule.

Portuguese and German were the mother tongues of our parents in virulently Afrikaans-speaking Pretoria in the 1970s. Being raised in a family where accented, broken English was the lingua franca, however, opened up many other paths to communication.

Read in Daily Maverick: "Where did this story that Afrikaans is a white person’s language come from?"

And so it was that Afrikaans acquired a generation of new speakers, while they in turn acquired and possessed it. Today it is spoken by about eight million South Africans.

Because of this, I could call Conservative Party leader and Dutch Reformed Church dominee, Dr Andries Treurnicht, from the Cape Town offices of the English-language Cape Times in the 1980s where I worked.

The instruction that evening was to seek his opinion on the announcement by President PW Botha of proposed “reforms” to apartheid, roundly rejected within and without formal politics. Naturally these “reforms” excluded the black majority.

Treurnicht had left the National Party in disgust to form the Conservative Party. He had been deputy minister of Bantu Administration and Education in 1976 when the Afrikaans-language policy was imposed on black students.

As an Afrikaner nationalist and neo-Calvinist he strongly supported apartheid, a policy later declared by the UN as a crime against humanity.

Treurnicht answered his landline at his home in Cape Town. It was late. Around 11pm. The story had been a leftover from the day shift. No one was keen to call up Treurnicht.

Offering comment to an English-language newspaper would have coloured how Treurnicht pitched his response. Our conversation in “algemeen beskaafd” Afrikaans was easy.

Being Catholic and unfamiliar with the bible – dogma being the preferred method of conjuring – I asked Treurnicht to explain what he had meant by “Ichabod” which he had used in his comment.

“Dan is dit Ichabod” (Then it will be Ichabod) he had replied.

It had something to do with the loss of the ark to the Philistines in Book of 1 Samuel, I later understood.

But this reporter’s lack of knowledge was an immediate alert to Treurnicht that he was speaking to an outsider, not someone raised Afrikaans and not a protestant.

But that is what happens when you force a language on a country and its people.

Afrikaans took me there right to Treurnicht on the other end of the line that night, but it also took me elsewhere.

In the 1980s it took me to the music of Johannes Kerkorrel, Koos Kombuis, Amanda Strydom and Piet Botha, the comedy of Casper de Vries and Nataniël. This was when white speakers of the language hurled it back at those who used it as a weapon.

The late South African singer, songwriter, journalist and playwright Johannes Kerkorrel. (Media24)

The late South African singer, songwriter, journalist and playwright Johannes Kerkorrel. (Media24)

It was in Antwerp, Belgium in the late 1980s when my dear friend, Belgian writer Tom Lanoye, convinced me to untether, once and for all, Afrikaans from its history and those who claimed it as their own.

The journey began and has never stopped.

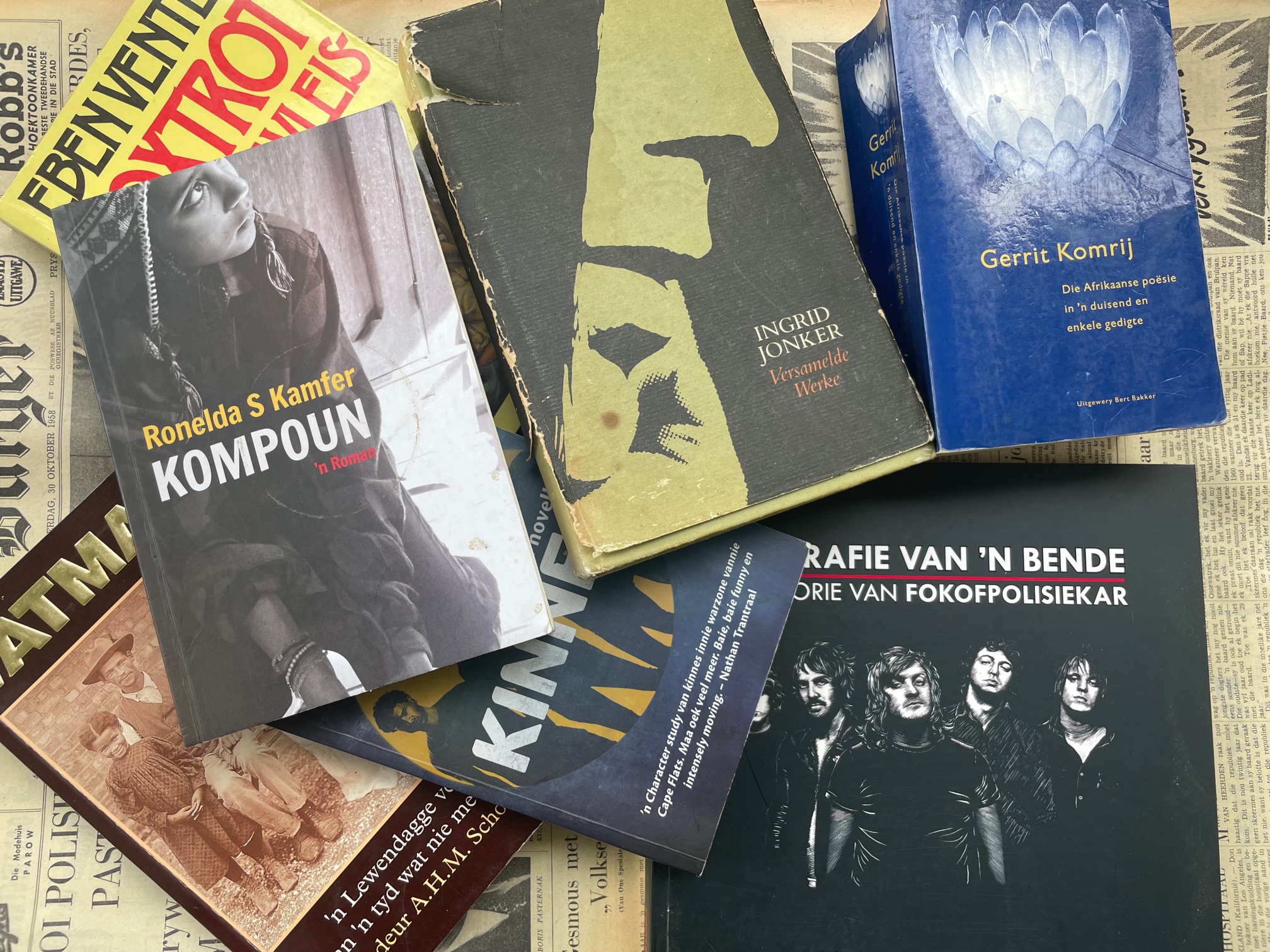

Along the way stood a stellar line of individuals who offered up the tongue in protest, defence and pushing the limits it imposed: Adam Small, Antjie Krog, Breyten Breytenbach, Ingrid Jonker, Andre Brink.

Today Afrikaans, to those who speak it, offers a smorgasbord of literary, artistic, musical, intellectual and cultural delights. More books are published in Afrikaans than any other indigenous language. It is celebrated in world-class, contemporary theatre at myriad festivals.

A thriving film and television industry provides work for thousands of artists, writers, actors, musicians, directors – black and white.

Many artists, particularly musicians, have made lucrative and enduring careers: Karen Zoid, Nataniël, Amanda Strydom, Fokoff Polisiekar, Youngsta CPT, Early B. The list is too long and keeps getting added to.

Early B performs at the annual Liefde By Die Dam at the Meerendal Wine Estate on November 12, 2022 in Durbanville. The much-loved Afrikaans pop-rock music festival is celebrated annually. (Photo by Gallo Images/Die Burger/Jaco Marais)

Early B performs at the annual Liefde By Die Dam at the Meerendal Wine Estate on November 12, 2022 in Durbanville. The much-loved Afrikaans pop-rock music festival is celebrated annually. (Photo by Gallo Images/Die Burger/Jaco Marais)

Black Afrikaans

As an author and chronicler of the history of black writers of Afrikaans literature, Professor Hein Willemse, of the Department of Afrikaans at the University of Pretoria, has written extensively on the subject.

In September 2019 he noted: “It is striking that not a single Black Afrikaans writer formally debuted between 1961 and the 1976 uprising.”

Willemse’s article was a complimentary piece to a 2002 paper by Professor Ampie Coetzee titled “Swart Afrikaanse Skrywers: ’n diskursiewe praktyk van die verlede” (Black Afrikaans writers: a discursive practice of the past).

It was 1985 when the first Black Afrikaans Writers Symposium, in association with the Department of Afrikaans and Dutch at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), took place. This was followed up in 1995, 2005 and 2015.

Notable here is the role of UWC) and its vice-chancellor, the iconic Jakes Gerwel (1987-1994), who inspired a generation of black professionals, activists and politicians. Or rather “coloured”, as the apartheid government would classify students attending this “bush” college at the time.

While back then Stellenbosch University was still a bastion of white Afrikanerdom, UWC was where revolution in Afrikaans was fermenting.

As Willemse records, the Black Afrikaans Writers symposia “brought together writers who had several characteristics in common”.

“They mostly shared a legislated racial classification and used the Afrikaans language as a medium of literary expression. They mainly came from the Afrikaans rural areas, were fairly educated and were born in the immediate post-1948 era.”

These writers “ascribed to divergent social identities and diverse political orientations, implicitly suggesting multiple ways of resolving the late apartheid crisis of the 1980s”.

These symposia, writes Willemse, had “bestowed an identity on a literary development that in crucial respects was antithetical to the dominant perceived notion of Afrikaans and Afrikaans literature as white, Afrikaner-centric, middle class, nationalist, pedestrian and for the most part, indifferent to the political struggles of black South Africans.”

Literary pioneers

Willemse cites a long, long list of the post-1976 wave of Black Afrikaans writers including Frank Anthony, Farouk Asvat, André Boezak, Floris A Brown, Leonard Koza, Shawn Minnies, Dikobe wa Mogale.

Then there is Frieda Gygenaar, Abraham Phillips, AHM Scholtz, EKM Dido, Karel Benjamin, SP Benjamin, Mathews Phosa, Allan Boesak, Zulfah Otto-Sallies, Loit Sôls, Clive Smith, Kirby van der Merwe, Joseph Marble, Elias Nel and Catherine Willemse, who were all published, notes Willemse, with “mostly mainstream Afrikaans publishers in the immediate thawing of the apartheid state”.

Former ANC Treasurer General, Mathews Phosa at the release party of his revised poetry book, Deur die Oog van 'n Naald, in Stellenbosch on Monday 14 September 2009. The 19 new poems was written during the ten-year Thabo Mbeki administration. (Photo by Gallo Images/Foto24/Natalie Gabriels)

Former ANC Treasurer General, Mathews Phosa at the release party of his revised poetry book, Deur die Oog van 'n Naald, in Stellenbosch on Monday 14 September 2009. The 19 new poems was written during the ten-year Thabo Mbeki administration. (Photo by Gallo Images/Foto24/Natalie Gabriels)

Subsequently a “third-wave”, a post-2000 generation “broadly categorised as black, has come to the fore,” notes the author.

These include novelists and autobiographers Simon Bruinders, Olivia Coetzee, Zain Eckleton, Jenna-Leigh February, Brian Fredericks, John Fredericks, Fatima [Osman], Hemelbesem (Simon Witbooi), Valda Jansen, Chys Rhys, Jeremy Vearey and Bettina Wyngaard.

Poets who have captured the times are Ronelda Kamfer, Lynthia Julius, Andy Paulse, Jolyn Phillips, Shirmoney Rhode, and Nathan Trantraal as well as playwrights Christo Davids and Amy Jephta.

Officially Official

In 2021, Minister of Higher Education Blade Nzimande announced that Afrikaans would no longer be considered an “indigenous” language.

Protest followed after the release of a Language Policy Framework for Public Higher Education Institutions which excluded Afrikaans, Khoi and San languages from the definition of an “indigenous” language.

By May 2022, Nzimande backtracked and declared all these tongues were from one mother and belonged along with the others.

It was a historic victory cementing the status of these languages and finally Afrikaans.

UWC has been at the forefront of liberating Afrikaans (there were some dissidents at Stellenbosch, however, fighting from within). Today Afrikaans is spoken without fear at UWC while at Stellenbosch it has become a fraught political football.

For some of us Afrikaans feels like home. DM/ML

Visit Daily Maverick's home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Former ANC Treasurer General, Mathews Phosa at the release party of his revised poetry book, Deur die Oog van 'n Naald, in Stellenbosch on Monday 14 September 2009. The 19 new poems was written during the ten-year Thabo Mbeki administration. (Photo by Gallo Images/Foto24/Natalie Gabriels)

Former ANC Treasurer General, Mathews Phosa at the release party of his revised poetry book, Deur die Oog van 'n Naald, in Stellenbosch on Monday 14 September 2009. The 19 new poems was written during the ten-year Thabo Mbeki administration. (Photo by Gallo Images/Foto24/Natalie Gabriels)