A crisis is brewing in local higher learning institutions over the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to cheat – and university authorities seem to be at sea over how to handle it.

Charne Lavery, associate professor in English at the University of Pretoria, first realised the scale of the problem when reading her 800 second-year students’ essays two years ago.

The submissions shared an uncanny uniformity – flawless grammar and impeccable format, but with a synthetic flatness that set alarm bells ringing.

“These essays just sounded completely different to what we would get in the past: this bland tone with a perfect essay structure,” says Lavery.

When run through a plagiarism detector that many universities rely on, Turnitin, most essays came back clean. Yet Lavery estimates that 70% to 80% of the essays were to some degree AI-generated.

The problem? “The burden of proof is on the academic. And there is really no way to prove it at all,” she says.

South African universities have battled funding crises, student protests and pandemic disruptions over the past decade.

Now they face an insidious new challenge: across the country, students are using ChatGPT and other ever more sophisticated large language models (LLMs) to generate essays, solve assignments and in effect cheat their way through their degrees.

The institutions are scrambling for ways either to stop them or to turn their use of AI into a positive academic tool.

Daily Maverick investigated how top local universities are handling this growing issue. The responses suggested a certain amount of institutional denial.

Meanwhile, academics on the ground describe a system struggling to keep up: unreliable detection tools, inconsistent policies and a generation of students who, after years of pandemic-era online schooling, never properly learnt not to cheat.

We asked a class of 26 postgraduate students at Stellenbosch whether they knew of someone who had used an LLM to cheat on a university assignment. Six did not reply; three said no; and 17 (65%) answered yes.

University of Pretoria's Professor Charne Lavery. (Photo: Ignus Dreyer)

University of Pretoria's Professor Charne Lavery. (Photo: Ignus Dreyer)

A problem that can’t be quantified

By definition, it is impossible to accurately assess the scale of this problem because of the difficulty of detecting AI-generated work. Although all the universities Daily Maverick contacted said they used plagiarism-detection software, no software can reliably detect AI bot language as yet.

Academics themselves, meanwhile, admitted that their ability to detect the use of LLMs in written submissions was limited.

“This cannot be overstated. Anyone who claims otherwise is a victim of hope and marketing,” said Dr Carla Lever, a contract lecturer in cultural studies who works at several Western Cape universities.

Dr Jonathan Shock, interim director of the University of Cape Town AI initiative, agreed: “Basically, there is very little possibility of [reliably detecting] this with any reasonably large cohort of students.

“The only option is when there are small groups of students where a lecturer knows the style of writing, and can then see the difference,” said Shock.

Particularly in South African undergraduate humanities and commerce courses, which have huge student intakes, the chances of this happening are vanishingly low.

Dr Carla Lever, who works at several Western Cape universities. (Photo: X)

Dr Carla Lever, who works at several Western Cape universities. (Photo: X)

Cheating en masse during Covid

Plagiarism – or, as some academics are now terming it, “traditional plagiarism” – has always been a problem for universities. But the cheating problem appears to have developed a new force and scale during the Covid-19 pandemic, when students were doing most of their learning online.

University of Johannesburg (UJ) history lecturer Dr Stephen Sparks told Daily Maverick that students began to lean heavily on online “paraphrasing tools”, which enable users to bypass plagiarism checkers by redrafting another person’s work using plenty of synonyms.

Sparks cited a now-legendary example of a South African student who included a reference in an essay to a paper from “Stronghold Bunny University”. This is a bot’s substitution for Fort Hare.

“We were seeing a lot of that in Covid and it just became really thankless and dispiriting,” said Sparks.

A philosophy lecturer, who asked to remain nameless, said pandemic-era schooling appeared to have accustomed some students to cheating as an academic way of life.

“The undergraduates we have now did a large part of their high school careers online. Not to sound grim, but they could basically cheat as much as they wanted to, without ever doing any research.

“I really think that the underdevelopment of these reading and writing skills is driving students to rely more and more on ChatGPT. They never learnt the skills, and why would they now, when there is a tool for it?”

The problem is not limited to the humanities and it has significant knock-on impacts.

Aidan Bailey, an assistant lecturer in the University of Cape Town (UCT) Computer Science department, expressed concern about the “foundational issues arising from early LLM reliance”.

“This is not to say that students relying on LLMs to cheat and complete assignments to a high degree of competency would be entirely handicapped,” said Bailey.

“I believe a crafty student, i.e. one who doesn’t just copy and paste but also curates the output, could probably scrape by second year. A particularly crafty student might even get the degree.”

He said there were even stories at this stage, less than three years after ChatGPT’s widespread adoption, of IT professionals who were entirely reliant on the service.

“I’ve heard of IT professionals holding very lucrative positions essentially secretly outsourcing their jobs to ChatGPT by screenshotting dashboards – sometimes holding sensitive data – then feeding them into ChatGPT, doing what it tells them and occasionally swearing loudly when it inevitably fails.”

Sparks pointed out that Silicon Valley tech firms are now themselves starting to reap what they’ve sown, with companies grappling with the problem of recruitment in an era where dependence on AI tools has become so prevalent.

University of Johannesburg's Dr Stephen Sparks. (Photo: University of Johannesburg)

University of Johannesburg's Dr Stephen Sparks. (Photo: University of Johannesburg)

What do the universities say?

Daily Maverick canvassed the following universities to assess their responses to the challenges posed by the new AI tools: UCT, Stellenbosch, Rhodes, Wits, UJ, Pretoria, Western Cape and the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT).

The CPUT struck a rare note by openly acknowledging how common the use of LLMs has become, with spokesperson Lauren Kansley saying: “There is no denying that students are making use of AI in their essays and assignments.”

Kansley also acknowledged “the danger of AI use and its impact on learning”.

Most universities, however, seemed keen to downplay the extent to which students are manipulating the system by using AI.

The University of the Western Cape’s Gasant Abarder said: “There hasn’t been a dramatic increase in submissions containing AI content.”

UJ’s Herman Esterhuizen said: “UJ has not encountered widespread misuse.”

Other institutions were at pains to reframe the issue more positively.

A spokesperson for Rhodes University responded: “This question assumes that using tools like ChatGPT is inherently cheating. This common framing stems from concern that the value of a university qualification is undermined by the use of ChatGPT and other [generative AI] tools, which is an incorrect assumption.”

Yet most universities simultaneously acknowledged that they have had to change their assessment practices in recent years to move away from essays completed at home.

“The CPUT is supporting academics in exploring alternative forms of assessment such as oral examinations, in-class presentations, reflective writing and collaborative projects that are more resistant to misuse of generative AI,” said Kansley.

She added that assignments involving computers now often require tools such as “lockdown browsers” to block access to the internet.

UJ said that where online assessments are still used, they are paired with measures such as “using tools to monitor students during assessments” and “requiring students to provide video evidence of certain tasks”.

UCT’s Sukaina Walji, director of the centre for innovation in learning and teaching, told Daily Maverick: “Lecturers are having to consider their assessments.

“In some cases, this has meant some moves to in-person invigilated assessments or other forms of assessment that we might class as ‘observable’, such as orals and vivas, to ensure that students do not have access to unauthorised AI tools.”

UCT's Sukaina Walji. (Photo: University of Cape Town)

UCT's Sukaina Walji. (Photo: University of Cape Town)

Move to handwritten essays

Academics confirmed to Daily Maverick that they have had to shift to alternative teaching and assessment methods. “In one of the third-year philosophy modules, the students now have to write their large research essay by hand during tutorial time slots instead of the usual arrangement whereby students do independent research over a number of weeks and type up an essay to then submit,” said the philosophy lecturer, who wanted to remain anonymous.

“The risk, and amount of AI submissions we’ve been getting, have simply become too large.”

The University of Pretoria’s Lavery said: “We do all assessments in person and that has impoverished the degree to a huge extent. Students no longer write long essays on their own; they do four-hour invigilated sessions.”

Even this practice has not proved infallible. Post-It notes to mark students’ reading had to be banned because students were printing out ChatGPT essays and cutting them into tiny squares.

Silver linings

Yet most academics also acknowledge that there are positive aspects to this unprecedented pedagogical situation.

“I have to thank AI for forcing us to think harder about what we are doing in the classroom,” says Sparks.

Universities say many staff members have incorporated AI into their teaching in positive ways.

Bailey told Daily Maverick that in Computer Science, the ability to engage with an LLM to “instantly generate explanations at various levels of abstraction, memorable limericks, exercises or examples, or personalised, understandable metaphors” was “an unbelievably beautiful notion”.

Lever is similarly enthusiastic about this aspect: “I condense theoretical readings into 10-minute podcasts through NotebookLM and play them in class to students. I love the ways that AI can be coded to work as a personal tutor. Gosh, we could never give each student that kind of attention.”

Other academics report that they have incorporated AI into their own work. Shock calls it a “collaborator” in his research, and uses it “to explore ideas, to find literature, to critique my writing, to suggest flows for a paper, to check at the sentence level for errors in my own writing, for helping me with coding, for suggesting novel projects”.

At the institutional level, however, there appears to be little consensus on how best to “ride the dragon”, as Sparks puts it – understandably, since the sophistication of these tools is now improving by the week and rendering the future of knowledge-based jobs increasingly uncertain.

Lavery said: “I suspect that universities are doubling down on the idea that this is not a problem because it is unmanageable.

“Universities, to their credit, are slow-moving beasts. They don’t jump to every fad. This is moving too quickly and there isn’t a good solution.”

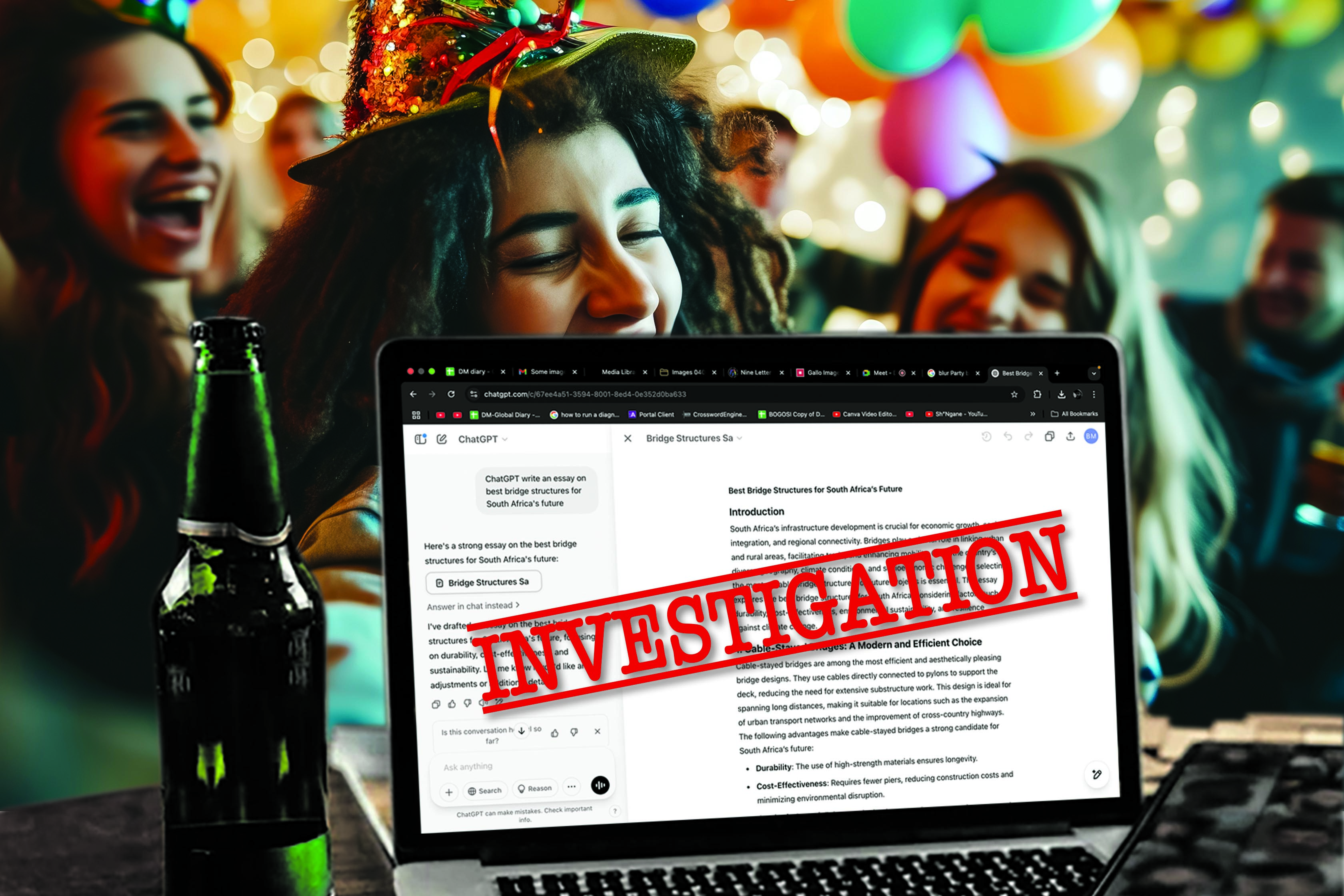

Example of an essay generated by ChatGPT

We gave ChatGPT this prompt: “Write a 300-word essay evaluating the ethics of using ChatGPT in academia.” It took milliseconds to produce the following:

Evaluating the Ethics of Using ChatGPT in Academia

The rise of AI tools like ChatGPT has sparked debates about their ethical implications in academia. While these tools offer benefits such as efficiency, accessibility, and assistance with research, their use also raises concerns about academic integrity, originality, and the potential for misuse. Evaluating the ethical implications of ChatGPT in academia requires balancing its advantages with the challenges it presents.

One ethical concern is plagiarism and academic dishonesty. AI-generated content can be used to complete assignments without genuine understanding or effort, undermining the learning process.

If students submit AI-generated work as their own without proper acknowledgment, they violate principles of academic integrity. Institutions must therefore establish clear guidelines on the responsible use of AI in coursework and research.

However, ChatGPT can also be an ethical tool when used appropriately. It can aid in brainstorming, summarizing complex ideas, improving writing skills, and even tutoring students in various subjects. For researchers, AI can help generate ideas, organize data, and refine arguments, enhancing productivity.

The key ethical distinction lies in whether AI is being used as an aid for learning or as a shortcut to avoid

critical thinking.

Another concern is bias and misinformation. AI models like ChatGPT are trained on vast datasets that may contain biases, and their responses are not always accurate.

Relying on AI without verification can lead to the spread of misinformation or reinforce biased perspectives. Ethical academic use requires cross-checking AI-generated information with credible sources and critical analysis of its content.

Ultimately, the ethical use of ChatGPT in academia depends on transparency, proper attribution, and responsible engagement.

Rather than replacing intellectual effort, AI should be integrated as a

tool that enhances learning while upholding academic integrity and ethical scholarship. DM

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R35.

Sukaina Walji. (Photo: University of Cape Town)

Sukaina Walji. (Photo: University of Cape Town)