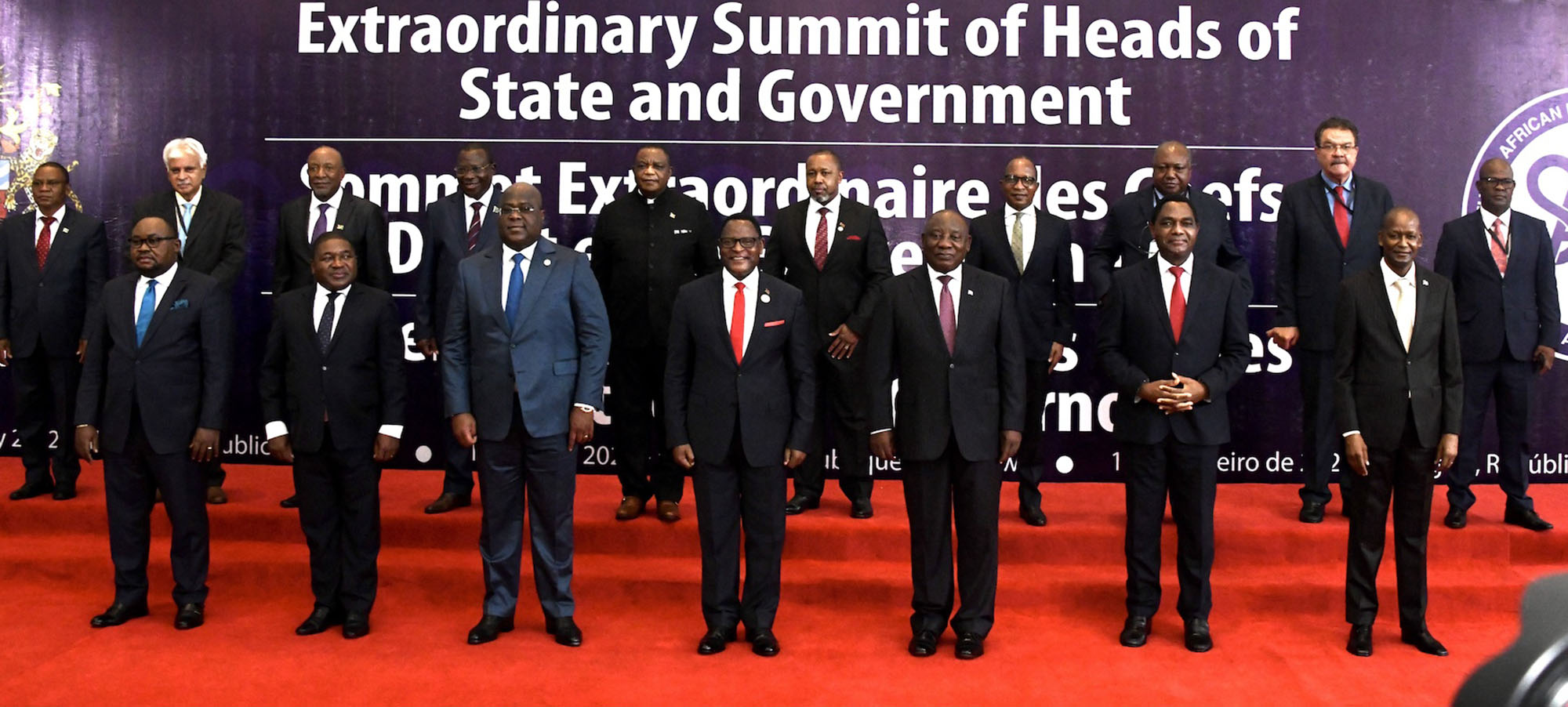

Any summit meeting such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Summit on Saturday, 17 August, inevitably raises questions about the success and failure of the organisation. This can be a narrow reflection on the past period, or it can focus more deeply on the utility of the organisation as a whole.

In the last Sapes Policy Dialogue, the broad question Whither SADC? was asked, and the reflection was pessimistic about SADC’s value, but not about the possibilities for SADC citizens.

Given that the SADC Treaty, first promulgated in 1992, espouses democracy, and that the world generally is in democratic recession, what progress has SADC made towards this goal? According to the Varieties of Democracy Index (V-Dem), and encouragingly in Africa generally, half of the SADC countries are going in the direction of democracy (Table 1), but equally half are not.

One critical litmus test, but not the only one, is elections, the basis by which countries can claim legal and legitimate governments, and it is elections that have become the manner in which democracy is being subverted. Half of SADC countries are regarded as electoral autocracies, in that regular elections are held but fail to meet the standards of genuine democratic elections. This is a prima facie violation of the SADC Treaty Principles that require “sovereign equality of all Member States; solidarity, peace, and security; human rights, democracy, and the rule of law; equity, balance, and mutual benefit; and peaceful settlement of disputes”.

Treaties, like any rule or law, imply both rights and responsibilities, and the SADC Treaty provides for actions to be taken if a country is in breach of its responsibilities: “Sanctions may be imposed against any Member State that persistently fails, without good reason, to fulfil obligations assumed under this Treaty; implements policies which undermine the principles and objectives of SADC.” (Article 33, 2015) This suggests that it is not only elections that can be in breach of the Principles, but also the broader political economy.

Elections according to SADC rules

SADC election observers in Marondera, Zimbabwe, in 2008. (Photo: Howard Burditt / Reuters)

SADC election observers in Marondera, Zimbabwe, in 2008. (Photo: Howard Burditt / Reuters)

Of course, it seems obvious that there must be some measure of “persistent failure”, and the hardest measure must be elections. Countries that fail this test must obviously be in primary facie violation of the Treaty. To SADC’s credit, the body decided in 2005 to create a basis for testing the validity of elections – the SADC Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections. These were specifically crafted to comply with the Principles in the SADC Treaty: … to promote the holding and observation of democratic elections based on the shared values and principles of democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights enshrined in the SADC Treaty signed at Windhoek, Namibia in 1992. The Principles and Guidelines are very explicit about what this means, elections that are “free” and “fair”, and are worth remembering.

“Free (elections)” means “Fundamental human rights and freedoms are adhered to during electoral processes, including freedom of speech and expression of the electoral stakeholders; and freedom of assembly and association; and that freedom of access to information and right to transmit and receive political messages by citizens is upheld; that the principles of equal and universal adult suffrage are observed, in addition to the voter’s right to exercise their franchise in secret and register their complaints without undue restrictions or repercussions.”

“Fair (elections)” means “electoral processes that are conducted in conformity with established rules and regulations, managed by an impartial, non-partisan professional and competent Electoral Management Body (EMB); in an atmosphere characterised by respect for the rule of law; guaranteed rights of protection for citizens through the electoral law and the constitution and reasonable opportunities for voters to transmit and receive voter information; defined by equitable access to financial and material resources for all political parties and independent candidates in accordance with the national laws; and where there is no violence, intimidation or discrimination based on race, gender, ethnicity, religious or other considerations specified in these SADC Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections”.

These are the two tests that must be applied if an election in a SADC country is accepted as meeting the principle of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. These are the tests a SADC Election Observer Mission (SEOM) must apply in observing an election, and there are multiple observations that must be applied in assessing these criteria.

Elections of course are very serious contests, all contests for political power are, and especially in deeply polarised countries such as Zimbabwe. Hence, electoral contests can be deeply conflictual, even violent. To SADC’s credit again, the body even goes further and has created a structure to deal with the possibility of conflict and violence – the SADC Electoral Advisory Council (SEAC), established in 2005, with a broad mandate to ensure that the member states of SADC adhere to the Principles and Guidelines, and obviously the Treaty itself.

The SEAC’s task is preventative and interventionist (implied) and covered in its Strategy for the Prevention of Electoral Related Conflicts. Its task is to examine an election in a SADC country before, during and after an election. Pre-election, the SEAC’s Goodwill Mission must advise the Ministerial Committee of the Organ (Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation) whether the election is “conducive to the holding of free, fair, transparent, credible and peaceful elections”. Additionally, the SEAC has to assess the election, and post-election compose a post-election review, which is of particular relevance should there be a conflict situation, and submit such a report to the Ministerial Committee of the Organ. This review also has to advise on what action needs to take place.

This is all very encouraging: principles for belonging to the organisation; penalties for failure to meet the principles; tests for legality and legitimacy; mechanisms for doing the testing; and a structure for preventing conflict and dealing with the same.

The big question, of course, is does this work, and what is to be done about Zimbabwe? Did it or did it not fail the SADC tests? And how bad is the failure according to SADC’s own rules? This is not purely about the last Zimbabwean election, but rather a case to decide whether the rules are merely rhetoric, a veneer rather than reality.

It is not contested by anyone that the SEOM gave the election a failing grade in 2023, nor that Zimbabwe failed completely in 2008, necessitating peaceful resolution of conflict through mediation, the Global Political Agreement, and the establishment of the Inclusive Government in 2009. Given this background, the SEAC undertook a Goodwill Mission in the pre-election period, but only arrived in April (12–19). It met with “various electoral stakeholders and concluded that the Republic of Zimbabwe was ready to hold Harmonised Elections in a calm and secure environment”. Furthermore, “no major incidences of concern were brought to the attention of the Mission during this period”. The SEAC report was included in the final SEOM report in three short paragraphs.

Well, the election did not seem to tick the boxes of “free” and “fair”, not to the SEOM but to other observer groups, such as the EU Observer Mission (EUOM), and the Carter Centre. Unfortunately, a major international stakeholder, the Commonwealth, has only provided a very preliminary report, and no final report nearly a year later. Thus, it did seem that the SEAC needed to deal with possible post-election fall-out, but the action taken by SADC was obscure. It deployed the SADC Mediation, Conflict Prevention and Preventative Diplomacy Structure, headed by the Panel of Elders, and technically supported by the Mediation Reference Group.

All well and good, but what has actually happened?

What might have been expected in 2023?

The reason for using Zimbabwe as a test case for SADC is quite simply that elections in Zimbabwe have been problematic since 2000. Objective evidence clearly shows that Zimbabwe is the most violent SADC country when it comes to elections, thus the probability for electoral violence should be seen as high. Secondly, Zimbabwe has had every election disputed since 2000, and one rejected in 2008. Elections have been one of the reasons for the imposition of restrictive conditions by the EU and the US, suspension by the Commonwealth (before Robert Mugabe unilaterally withdrew from it). Local commentators had been reporting about violence and intimidation since 2021, and there was serious dispute over the running of the elections – the voters’ roll, delimitation, etc. A pre-election audit by civil society pointed out that the conditions for holding free and fair elections were not present, conclusions somewhat at variance with those of the SEAC.

Finally, it was evident that the 2023 elections were not peaceful. Human rights reports showed high levels of political violence and intimidation both pre-and post-election, consolidated by a recent qualitative report by ZimRights, Perennial Course of Organised Violence, Torture and Voter Suppression. For the SEAC, the writing was on the wall, way before April 2023, and with some diligence it could have had a much more nuanced understanding of the likely outcome. This is the value of paying attention to many sources of “objective” evidence on a country: V-Dem, for example, and this data would corroborate the claims being made by Zimbabweans. This implies that the interregnum between elections is as important as the immediate election phase, the usual 90 days prior to polling. In fact, the SEAC itself recognises this, as pointed out in Article 1.7:

“Electoral related conflict and election violence has its roots in structural and systemic elements that extend beyond the events that are directly related to an election. Elections are not the root cause of conflict but they can trigger violence. The process of competing for political power often exacerbates existing underlying tensions and triggers the escalation of these tensions into violence. An effective strategy for the prevention of electoral related conflict needs to address the proximate and structural causes of electoral conflict and violence, as well as the events that trigger rapid escalation.”

This implies a monitoring process more extended than visits six months before an election, and a process of engaging “various stakeholders”.

Did SADC pass the test?

Thus, it is incontestable that Zimbabwe remains in crisis, and in conflict. Even the Zimbabwe government provides the evidence that it is in conflict: why else are 160 people in preventive detention (some even tortured)? Why are the police and army deployed around the country to prevent dissent? The rhetoric of the Zimbabwe government is of a peaceful and prospering country, but the reality is that it fears peaceful protest and demonstrations.

However, this is about evaluating SADC and its adherence to its own Treaty and Principles, and some hard questions need to be answered. Where is the SEAC pre-election review, and is there a more detailed report that would rebut the assertions made by Zimbabweans? Where is the SEAC post-election report, and why did SADC need to deploy the Panel of Elders and the SADC Mediation, Conflict Prevention and Preventative Diplomacy Structure?

What is the final decision on the SEOM report? The silence from SADC (and even the Commonwealth) creates no confidence that SADC takes its own Principles seriously. Or is it that “sovereignty” trumps everything? Did Zimbabwe pass the “free” test? Did Zimbabwe pass the “fairness” test? Does Zimbabwe uphold the SADC Principles?

Above all, where does SADC go next, and not merely in respect of Zimbabwe? Having taken the bold step to evaluate the Zimbabwe election in 2023 negatively, how will this play out in the elections to come in Mozambique, Namibia and Botswana?

When it comes to Zimbabwe, perhaps SADC should pay attention to one of its former presidents, Joachim Chissano, who pointed out that Zimbabwe has become a regional problem, and to the observation made by Clayson Monyela, spokesperson for South Africa’s Department of International Relations and Cooperation (Dirco), that dialogue would be the best solution for Zimbabwe. Zimbabweans would undoubtedly agree, but for SADC does this mean quietly waiting to be invited to help or more assertively (and perhaps in concord with the Treaty) to suggest that this should take place? As was pointed out 18 months ago, Zimbabwe has reached a” Lancaster House” moment – a regional crisis – and that requires more than the region sitting on its hands and waiting to be invited. DM

Ibbo Mandaza and Tony Reeler are co-conveners of the Platform for Concerned Citizens.

SADC election observers in Marondera, Zimbabwe, on 21 March 2008. (Photo: Howard Burditt / Reuters)

SADC election observers in Marondera, Zimbabwe, on 21 March 2008. (Photo: Howard Burditt / Reuters)