The Constitutional Court has ordered Home Affairs Minister Aaron Motsoaledi to pay 10% of the legal fees incurred in a case his department brought to court in the hope of getting an extension on a lapsed court order.

The department’s director-general, Livhuwani Makhode, has been ordered to pay 25% of the legal fees and the court has ruled that the lawyer who worked on the case, advocate Mike Bofilatos SC, should not receive a cent for work done on the application.

The decision to award a personal cost order against a member of the executive or a government official is something not often done by the Constitutional Court and is applied in instances when the party’s conduct shows serious disregard of the court.

The judgment is a result of a case brought by Home Affairs, attempting to “revive” a court order that lapsed in 2019. The original court order found that section 34.1(b) and (d) of the Immigration Act were invalid and unconstitutional. The sections authorised the administrative detention of undocumented foreigners for the purposes of deportation.

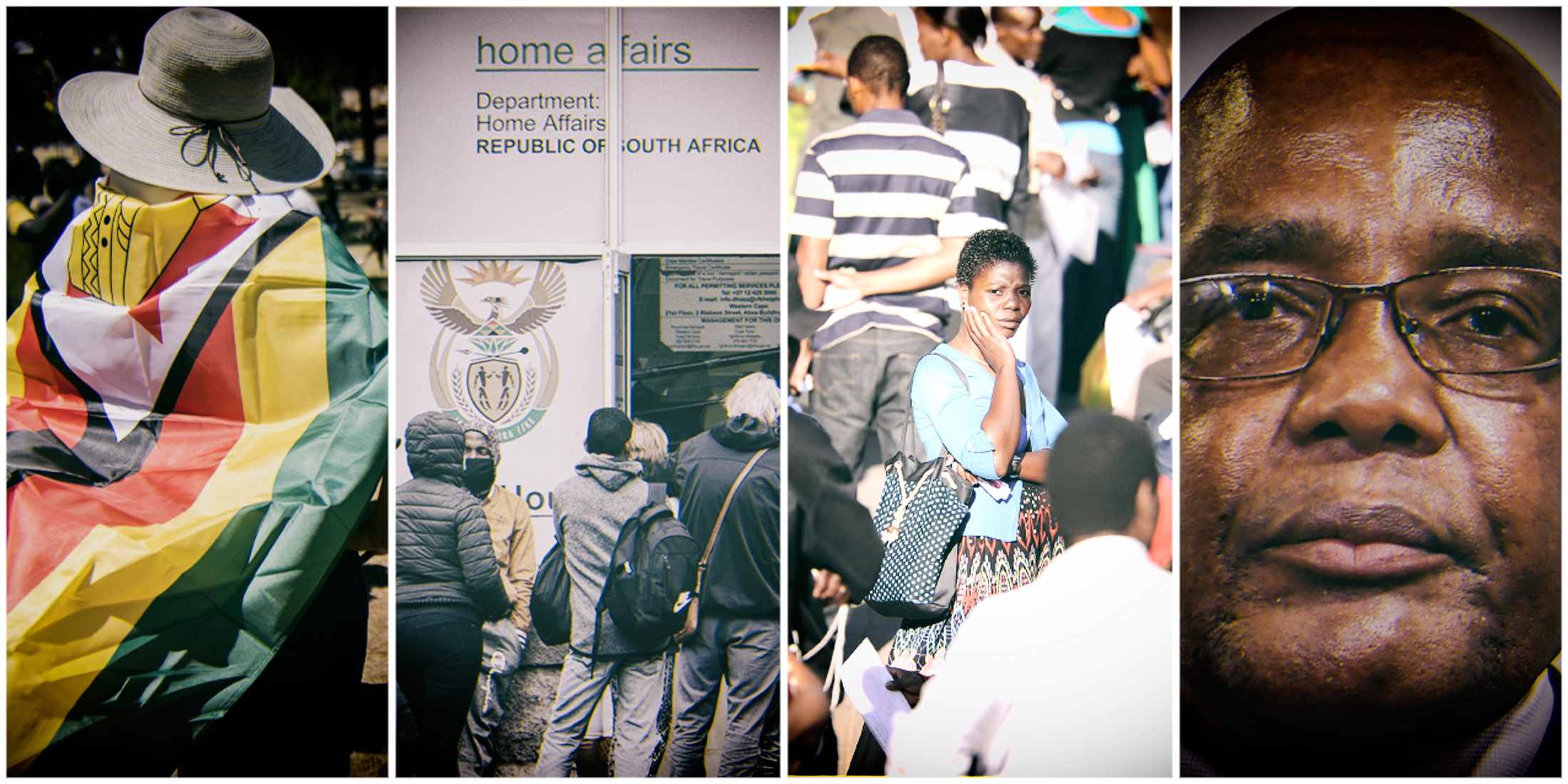

Hundreds of immigrant men on the other side of the Repatriation Tunnel at the Lindela Repatriation Centre in Krugersdorp, on 24 October 2006. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media24 / Lisa Skinner)

Hundreds of immigrant men on the other side of the Repatriation Tunnel at the Lindela Repatriation Centre in Krugersdorp, on 24 October 2006. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media24 / Lisa Skinner)

The detention period can be extended by a court from 30 days to 90 days or a maximum of 120 days. In 2016, Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR) argued that, in many cases, people were being detained for more than 120 days – sometimes for six months or longer – without appearing in court or being informed of their rights.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Aaron Motsoaledi must take responsibility for Immigration Act mess – Lawyers for Human Rights

The 2017 court order gave the department and Parliament 24 months to amend the legislation and suspended the invalidity for that period. Neither Parliament nor the department requested an extension and instead approached the high court and Constitutional Court in 2023, trying to get the order revived.

Personal costs

In deciding whether Motsoaledi and Makhode deserved to be punished personally, Justice Steven Majiedt considered the steps the department took in bringing the case to the high court and Constitutional Court. In both instances, the case was brought as an ex parte application, meaning the LHR, which brought the initial matter in 2016, was not informed.

Majiedt said it was “inexplicable” that the LHR was not informed in both instances because it “was plainly a necessary party with a direct and substantial interest in the matter”.

“Secondly, there was no mention at all of the fact that the deadline for the enactment of remedial legislation had expired. Nor was the High Court’s attention drawn to the four judgments of this Court cited above that stood in the way of the extension of a deadline that has expired. Again, this was either as a result of troubling ignorance on the part of the lawyers or, if those lawyers were aware of the quartet of cases, even more troubling, a failure to alert the Court to them,” he said.

Majiedt said the high court would not have had any power to overturn or extend a Constitutional Court order and there was existing case law on the issue.

“As stated, even this Court does not have any power to extend the deadline of a suspension after the deadline has expired. This is now the fifth time that this Court says so,” he said.

During the hearing, the lawyer for the department had been asked why Motsoaledi and the department had not apologised for ignoring the court deadline.

“There is not even the remotest hint of an apology by the Minister and the Director-General in the papers for the deplorable state of affairs in this matter. Their counsel appeared perplexed when this was raised with him during the hearing, almost as if the very idea of an apology was utterly unthinkable.

“Quite to the contrary, counsel startlingly suggested that the Minister and the Director-General should be commended for approaching this Court to address the conundrum that has arisen due to the Magistrates’ refusal to hear section 34 applications. This is an egregious aberration,” Majiedt wrote.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Zondo questions ‘pathetic dereliction of duty’ after Home Affairs ignores ConCourt order for three years

‘Dreadful’ conduct

The excuses provided by the department, blaming Covid and the fire at Parliament, did not carry water, Majiet wrote.

“The Covid-19 pandemic and resultant national lockdown occurred in 2020. The suspension of invalidity, however, expired almost a year earlier, on 29 June 2019. The devastating fire at Parliament erupted on 2 January 2022, nearly 18 months after the expiry of the deadline. The explanation that MPs became preoccupied from October 2018 with the looming national elections of 2019 and were unable to attend to passing the remedial legislation, is disconcerting.

“It is a grim acknowledgement, on the face of it, that campaigning for re-election was far more important to the Members of Parliament than meeting the deadline for the enactment of remedial legislation,” he said.

Majiedt wrote that even though errors are part of human nature, what happened in this case “goes far beyond human error and good faith mistakes”.

“I have been at great pains to describe in detail the flaws and the unsatisfactory manner in which the litigation has been conducted. This is because of the serious implications an order depriving the legal representatives of their fees and a personal costs order against the Minister and the Director-General may have. It can hardly be disputed that this litigation has been conducted in a dreadful manner. It is deserving of a punitive costs order,” he said.

The court found that even though Motsoaledi had said he was in the dark about what had happened in the case, he could not be absolved “from culpability for the shambles in this case”.

“The Minister is ultimately accountable for the fulfilment of the objectives of his Department and for the actions or failures of his officials. And it is the Minister who bears responsibility for the powers and functions of the executive assigned to him. As a Member of Cabinet, he is accountable to Parliament for the exercise of his powers and the performance of his functions. Apart from the Minister’s constitutional responsibilities and accountability, an important further consideration is that a higher standard of conduct is expected from public officials,” he said.

Majiedt said the court accepted what Motsoaledi had said about being kept in the dark by officials, and set his personal fee payment at 10%. Makhode’s penalty is set higher because, on his own version, he “admits to gross negligence”, the court said.

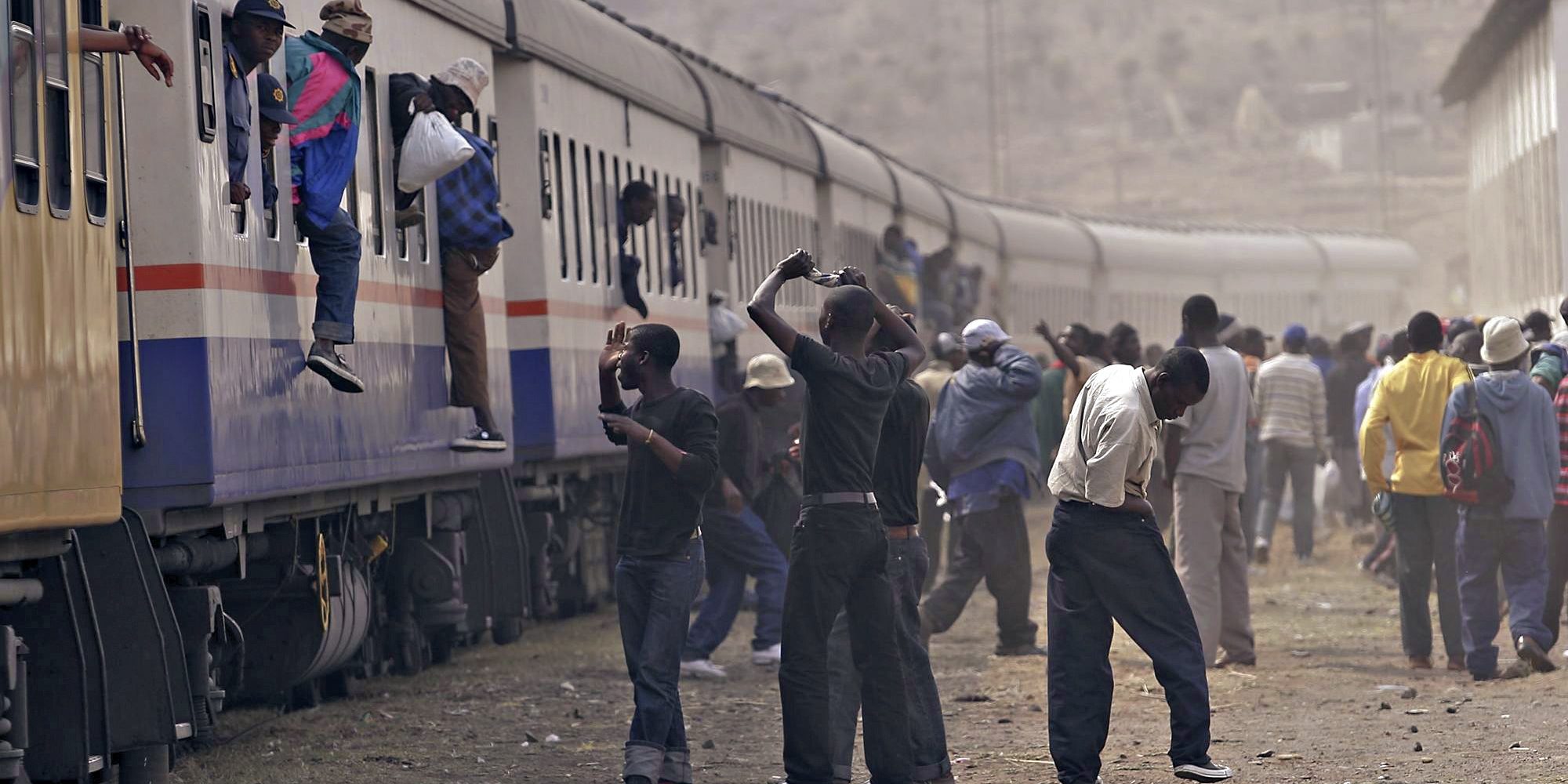

Arriving in Mozambique after a 14-hour train journey, passengers repatriated from South Africa in 2006 are desperate enough to disembark through the windows before the train has come to a standstill. The trip was part of a repatriation project by the Lindela Centre in Krugersdorp. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media24 / Lisa Skinner)

Arriving in Mozambique after a 14-hour train journey, passengers repatriated from South Africa in 2006 are desperate enough to disembark through the windows before the train has come to a standstill. The trip was part of a repatriation project by the Lindela Centre in Krugersdorp. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media24 / Lisa Skinner)

“The Director-General is the most senior official in a government department and is its accounting officer. They are expected to lead by example. The conduct displayed in this case is unacceptable and deserving of censure. The personal costs order that will follow is a mark of this Court’s displeasure at the Director-General’s conduct. On these facts, his culpability for this shambolic litigation plainly exceeds the Minister’s. In my view, the Director-General must be held personally liable for 25% of LHR’s costs,” he said.

Directions on deportation cases

The court also grappled with what remedy to institute since the two sections of the Act remain invalid. This is mainly because magistrates have been left with little clarity on what to do when faced with deportation cases, and some have refused to hear the cases.

“On the common cause facts, some Magistrates are unwilling to entertain any form of enquiry under section 34 (of the immigration act to determine whether the person entered the country illegally). This is highly unsatisfactory. As stated, the unwillingness of some Magistrates to confirm detentions beyond 30 days leads to releases from detention almost as a matter of course, even in cases where deportation should occur.

“That results in deportees likely absconding, rendering their deportation impossible. On the other hand, some immigration officers as a matter of course detain an immigrant beyond 30 days without bringing that detainee before a court, further violating their rights to liberty. This, too, is unsatisfactory,” he said.

The court has ordered the government to enact new legislation within 12 months.

In the meantime, immigration officers considering the arrest or detention of a suspected illegal foreigner “must consider whether the interests of justice permit the release of such person subject to reasonable conditions, and must not cause the person to be detained if the officer concludes that the interests of justice permit the release of such person subject to reasonable conditions”.

Someone who is detained must be brought before a court within 48 hours of their arrest. The court also provided directions for how magistrates should handle these hearings. DM

Arriving in Mozambique after a 14-hour train journey, passengers repatriated from South Africa in 2006 are desperate enough to disembark through the windows before the train has come to a standstill. The trip was part of a repatriation project by the Lindela Centre in Krugersdorp. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media24 / Lisa Skinner)

Arriving in Mozambique after a 14-hour train journey, passengers repatriated from South Africa in 2006 are desperate enough to disembark through the windows before the train has come to a standstill. The trip was part of a repatriation project by the Lindela Centre in Krugersdorp. (Photo: Gallo Images / Media24 / Lisa Skinner)