For decades, the United States has been a critical player in supporting the response to HIV/Aids in southern Africa. However, recent shifts in US policy as mandated by executive orders from the second Trump administration threaten to disrupt life-saving humanitarian aid programmes, posing profound danger to pan-African public health and economic stability, in addition to global health security.

Southern Africa has long been the epicentre of the global HIV/Aids pandemic, with Botswana, South Africa and neighbouring countries experiencing some of the highest infection rates in the world – in several cases exceeding 20% of the total adult population.

Botswana, for example, has an adult HIV prevalence rate of about 23% (for reference, any country with HIV infection rates above 1% is determined a Generalized HIV Epidemic per the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/Aids); South Africa, the most affected country worldwide by case volume, has an estimated 7.7 million people, people living with HIV/Aids, of which 5.9 million are on antiretroviral therapy.

World’s largest commitment

The United States’ President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (Pepfar), the largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease, has been instrumental in providing southern African countries with life-prolonging HIV-suppressing therapies and supporting prevention programmes. A sudden withdrawal of funding would negate decades of progress and jeopardise the health and lives of millions of African citizens.

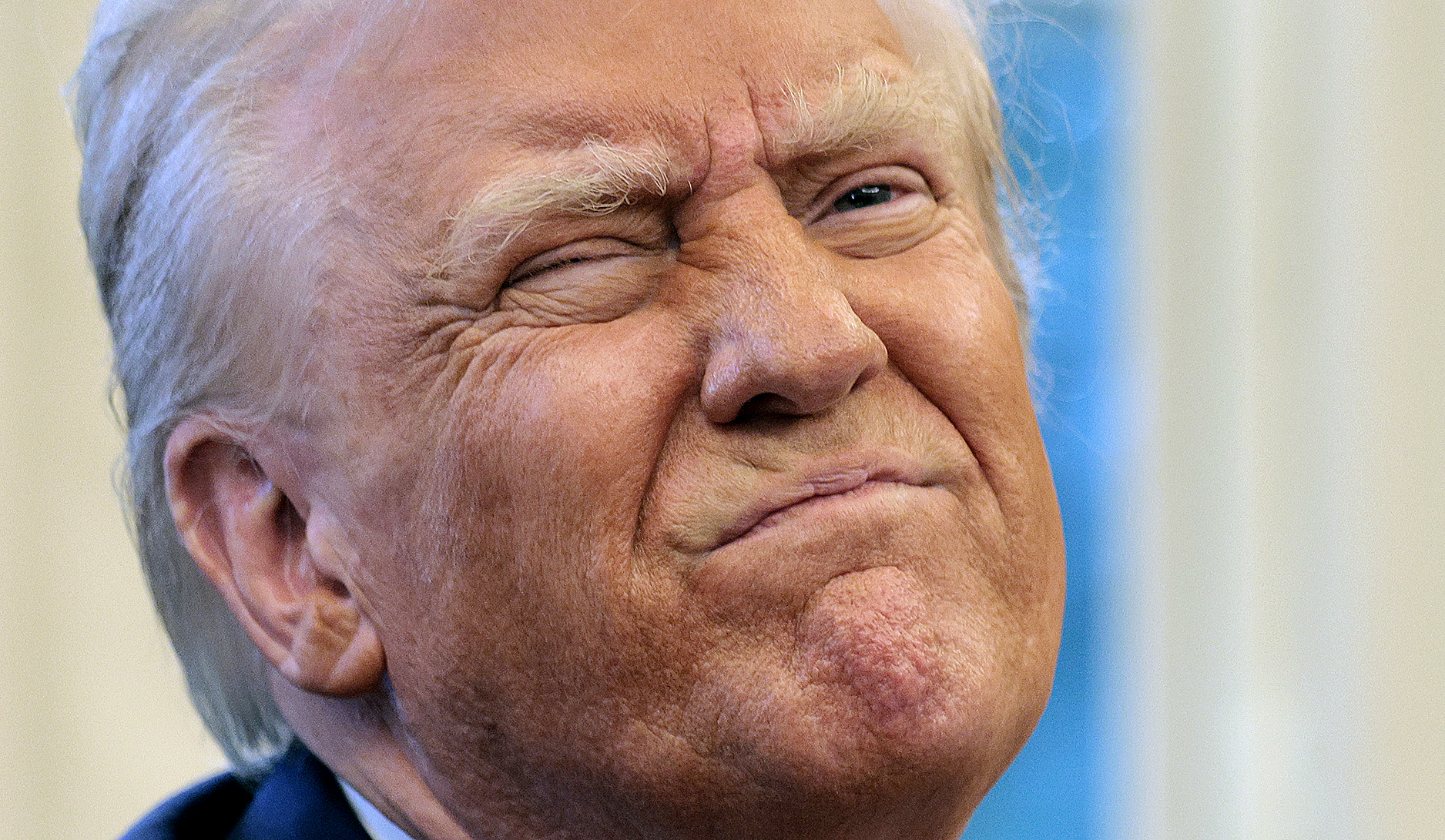

Recent US presidential executive orders targeted at scaling back US foreign aid render Pepfar’s future efficacy and existence uncertain. While government funding for Pepfar was granted temporary permission to continue shortly after President Trump signed a 90-day pause on disbursement of US foreign aid into effect, the absence of clear commitments has created an environment of uncertainty.

Further, America’s retreat from the international humanitarian stage goes beyond its direct aid: the US withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO) and other multilateral political bodies will compound the challenge, reducing international coordination and undermining public confidence in the global fight against HIV/Aids. Just recently, the South African USAid/Pepfar co-operative agreements were terminated, with little hope of these agreements being rescinded.

Global funding for HIV/Aids is carried out by a complex network of domestic, international and private partnerships, none of which are immune to disruption in the face of a seismic shift in US foreign aid policy.

South Africa funds most of its programmes for HIV therapeutics domestically, but external support remains essential for prevention, education and rural outreach initiatives. Through Pepfar, the US funds nearly 20% of South Africa’s $2.3-billion annual HIV/Aids programme, and, since its inception in 2003, has disbursed over $120-billion globally with billions allocated specifically to the southern Africa region.

South Africa alone has received more than $7-billion in funding. Additionally, USAid, a primary target of Trump administration funding cuts and key implementer of US global health strategy, has financed numerous HIV/Aids treatment and prevention programmes globally.

International disease management

The WHO, from which Trump re-issued a notice of intent to withdraw within days of taking office, plays a critical role in international disease management guideline development, supply chain logistics and coordination of care.

The potential consequences of reduced US support are dire. A disruption of current HIV/Aids mitigation programmes in southern Africa would lead to decreased access to critical treatments and preventive therapies, which would in turn lead to increased mortality and mother-to-child transmission. Beyond the immediate human toll, the economic losses and risk for spread of the virus to neighbouring regions would be substantial.

A recent historical example highlights in concrete terms the potential consequences of a break in foreign aid: between 2000 and 2005, then South African president Thabo Mbeki and his health minister, the late Manto Tsabalala-Msimang, rejected novel treatments for HIV/Aids, painting life-saving medications as toxic.

During this period, it is estimated that more than 330,000 South Africans died prematurely from HIV/Aids-related causes and at least 35,000 infants were born with preventable HIV infections. Given the extent of US support for HIV/Aids in South Africa and neighboring countries, the impacts of prolonged funding cuts are likely to be felt for generations.

The preceding example also highlights that an absence of authoritative public health messaging risks exacerbating misinformation about HIV/Aids, further reducing treatment adherence and uptake of preventive measures. (A core component of Pepfar’s mission is public health education and outreach.)

Perception of unreliability

Even if funding is restored in the future, the perception of US unreliability may undermine long-term public health collaboration and messaging. Additionally, as US influence declines, other nations such as China and Russia may seize the opportunity to expand their presence in the region through alternative aid and development programmes.

Affected African governments and international organisations must address the current disruptions and buffer this sudden withdrawal of funding by exploring alternative strategies. Diversifying funding sources is crucial and will require increased domestic budget allocations and greater reliance on contributions from the Global Fund to Fight Aids and other multilateral institutions.

Strengthening public-private partnerships can help offset the shortfall by encouraging pharmaceutical companies and philanthropic organisations to increase their investment. Regional cooperation among southern African nations should also be encouraged to create self-sustaining HIV/Aids programmes. Finally, diplomatic efforts must continue to pressure the US government to reconsider funding cuts.

The threats posed by the withdrawal or reduction of US support for HIV/Aids programmes in southern Africa extend beyond immediate health outcomes: such actions affect diplomatic relationships, international collaborations and the broader fight against infectious disease burdens globally. While efforts to mitigate these consequences are under way, there is no doubt that the loss of US engagement in global health initiatives will leave a lasting impact on one of the most vulnerable populations in the world. DM

Dr Wilmot James is a Professor and Senior Advisor to the Pandemic Center in the School of Public Health at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island; Dr Stefanie Psaki is a Distinguished Senior Fellow in Global Health Security at the Brown University School of Public Health and former US Coordinator for Global Health Security in the Biden White House; and Dr Glenda Gray is a Distinguished Professor and Director at the Infectious Disease and Oncology Research Institute, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.