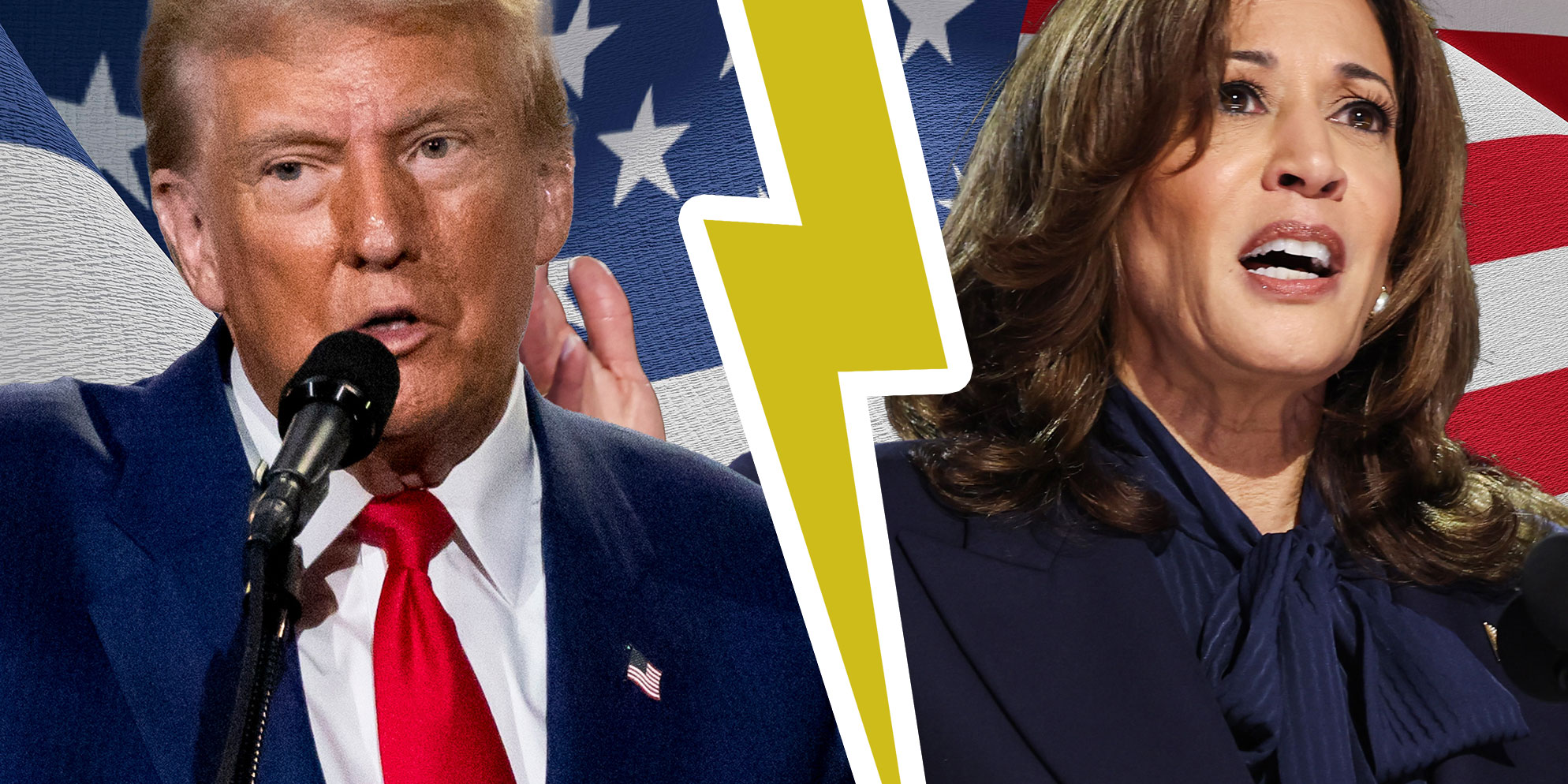

On Tuesday night in Philadelphia, US Vice-President Kamala Harris and former president Donald Trump will meet for the first — and perhaps only — time in this year’s presidential campaign. The proceedings will be broadcast and streamed on ABC Television and multiple other channels. The audience will be numbered in the many millions in the US and around the world.

Do such events matter? Why? Will they affect the dynamics of the ongoing presidential race? How?

One response, of course, is an acknowledgement of the reality that events like this one have little to do with the actual processes of governance or the skills of the candidates in governing. Too often, they take on the characteristics of a pre-scripted pageant in which there is much sound and fury, but little real content.

Increasingly, candidates are carefully primed with pre-prepared one-liners and clever zingers designed for point-scoring. That is in contrast to an effort to help voters make informed choices by providing them with serious insights about the timbre, quality, competence, skills, background and maturity of the candidates.

Increasingly, many of those one-liners are designed so they can become clips on news broadcasts, then segue into campaign commercials, and are further propagated on social media. Such clips may never fade from the collective memory of the internet and will pop up repeatedly.

Moreover, rather than watching the full debate, such telling moments are probably the only parts of the debate most voters see.

Texture of history

Having said that, we can argue that debates have had significant impacts on campaigns and electoral races. In some cases, they have become part of the texture of history.

Moreover, the very notion of a debate has become a default element in elections, well beyond the US, as candidates confront their opponents in live, unscripted, broadcast events. We now frequently hear the clamour for candidate debates in many other nations, based on the US example and experience.

In the modern sense, candidate debates in the US began with a series of seven debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas, competing in a race for a Senate seat in Illinois, in 1858. Douglas was the incumbent senator and Lincoln was the challenger.

Douglas, “the Little Giant” on the grounds of his height, already had a national reputation as a politician, orator and supporter of legislative compromises in the matter of the legal existence of slavery. Lincoln had a very modest political résumé as a one-term congressman, but an established career as a successful attorney for the railroads that were expanding across the state, as well as a rising reputation as a public speaker on national issues.

The two men travelled across Illinois to spar with each other in seven debates, each lasting three hours and without a significant role for media stars as moderators/interrogators. The debates were not aimed at winning the state’s popular vote, because senators were still selected by state legislatures. Instead, the point of the debates was to influence the Illinois legislators’ choice through the swaying of public sentiment.

There was no electronic media to record the proceedings, but skilled transcribers made summaries and full transcripts (using the newly invented Pitman shorthand) that were quickly circulated to all of the state’s many newspapers via telegraph and railroad lines — and then on to the rest of the nation.

After the debates, Douglas won reelection, although he only served two years of that term, dying in 1861. However, the evidence of Lincoln’s rhetorical gift turned him into a national figure.

Together with some canny stage-managing by supporters, he became the still-new Republican Party’s nominee for the 1860 presidential election. He won in a four-candidate election that featured his Republicans as well as two versions of the Democrats and a remnant of the Whigs, Lincoln’s former party. His victory allowed him to lead the nation through the Civil War and then on to the end of slavery.

In the debates and his initial run for the presidency, Lincoln had not yet become a full-scale opponent of slavery. That came later, but by 1858 he was already opposed to the “peculiar institution’s” extension into territories beyond those states where it was still legal. While this was not a winning formula in 1858 for his Illinois senatorial race, it was sufficient for the presidential race two years later.

Nixon vs Kennedy

However, it was not until the 1960 presidential race that debates became a frequent fixture of US presidential politics. Debates are not a constitutional requirement, or even a legislatively prescribed one, but the clash between Vice-President Richard Nixon and Massachusetts Senator John F Kennedy set a pattern that has frequently been observed in the years that followed.

From 1976 onward, debates have almost — but not always — been a fixture of presidential campaigns (before the selection of party candidates and then in the run-up to the general election) and are almost inevitable in races down-ballot as well.

In the 1960 debate, on the television screen, Kennedy looked poised, energetic, telegenic and healthy. Some of that was due to serious preparation and practice at a Florida beach resort where, amidst the debate prep, he also soaked up sun and exercise.

Nixon, by contrast, had eschewed any TV makeup and he looked pale and sickly as he sweated through the debate in a light grey suit. A failure to get a really good shave just before the broadcast gave him that infamous five o’clock shadow that became a gift to political cartoonists like Herblock at The Washington Post for years.

Campaign strategists have taken note of such things ever since, realising the visuals of a candidate are at least as important as what he or she actually said. Interestingly, people who listened on the radio, contrary to television watchers, believed Nixon had won that 1960 meeting and that he had demonstrated a better understanding of international affairs than Kennedy.

Over the years, another lesson learned from the presidential debates is that a well-chosen one-liner, a gentle joke with a barbed, steel core is also crucial for debate success. This was true in 1984 when Ronald Reagan destroyed the somewhat younger Walter Mondale in their second debate, quipping he would not take advantage of Mondale’s relative youth and inexperience in their debate.

Reagan was a seasoned actor with a skilled sense of timing. Mondale was an earnest, experienced politician and former vice-president, but not an especially humorous figure. That one moment of seemingly spontaneous, but well-prepped levity became crucial for Reagan’s chances, especially since in his performance in their first debate he had come across as ill-prepared, ill-at-ease, not particularly knowledgeable and… old.

Then there are the self-inflicted wounds that demonstrate a candidate is not ready for prime time as a president. There is the sad example of Gerald Ford. He had been appointed vice-president after Nixon’s original vice-president resigned in the wake of well-founded charges of bribery and corruption. Ford then succeeded Nixon as president when Nixon himself resigned in 1974 rather than be impeached and convicted over the Watergate scandal.

In the 1976 presidential debate, Ford faced former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter, who had not yet been locked down in the public mind as the best man for the job. For whatever reason, Ford, in an effort to show solidarity with the oppressed nations of Eastern Europe then under Soviet Union control and demonstrating his support for the ideas of democracy and freedom, said the Polish people would never be dominated by the Soviet Union.

This was a reference to their collective state of mind, but quite clearly not to the reality of a rather large Soviet military establishment in residence in Poland and the Soviet Union’s effective control over that country’s political life. Public incredulity at Ford’s seeming naivety and ill-adroitness helped solidify his reputation as a bumbler — and a not particularly smart one. It was all downhill for Ford’s campaign thereafter.

In 1988, the race was between Vice-President George HW Bush and Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis. The contest seemed close until Dukakis gave an ill-fated response to a question in their televised debate. CNN’s Bernard Shaw, serving as moderator and interrogator, asked Dukakis — given his opposition to the death penalty — how the candidate would feel if his wife, Kitty, was raped and murdered by a man out on bail for charges of another vicious crime.

Dukakis proceeded to take the question as the kind of discussion that belonged in a law school tutorial or an abstract Socratic dialogue, explaining his principled opposition to the death penalty. This came from him rather than the fact that the country was a nation of laws, even though he would have personally been enraged and angry and would have felt the emotional need for revenge.

It went downhill from there for the candidate. He never regained his footing, especially after he was hit with Republican campaign ads about Willie Horton, a convicted violent criminal in Dukakis’ home state, who while out on early release committed a rape/murder in Maryland.

More recently still, there is the memory of Trump, in his encounter with Hillary Clinton, who had made use of his physical domination of the debate stage to unsettle and belittle his opponent. And then, of course, there is the most recent example of the Trump-Biden collision in which the president was effectively the instrument of his own undoing, leading to his withdrawal from the race and his replacement by Harris.

The Prosecutor and the Felon

This Tuesday, we will get to judge the winner on the television show “The Prosecutor and the Felon.” We need to be conscious about whether it will show if Harris’ modest bounce in popular support is real and growing, or if Trump behaves in a way that proves — once and for all — he is unsuitable for this job.

As Washington Post commentator Dan Balz noted at the weekend, “Ever since President Joe Biden ended his candidacy and Vice President Kamala Harris became the Democratic nominee, former president Donald Trump has struggled to adapt to the new opponent. Tuesday’s debate in Philadelphia should show what, if anything, he has learned about running against her.

“Presidential debates often don’t matter much. The Trump-Biden debate in June in Atlanta was the rare exception: an event that changed the course of history and the 2024 campaign. No one expects the Philadelphia debate to be as cataclysmic for either candidate. But given the state of the race, there’s little doubt that the stakes are much bigger than usual and that mistakes will be consequential.”

Balz argued that “a series of tests confront Trump heading into Tuesday’s event, about self-discipline, knowledge, his age and acuity, his overall temperament, and how he deals with the issues of race and gender. For the past six weeks, he’s often been failing those tests.

“His campaign team has been virtually shouting for him to focus on the issues where he has the advantage and Harris the disadvantage. He obliges but seemingly without commitment. He’d rather talk about grievances than issues, and so he struggles to stay on track, veering from one thought to another, disconnected, thought. His base may love it, but that base isn’t big enough to win the presidency.”

Meanwhile, the Democratic nominating convention speeches by Harris and her running mate, Tim Walz, showed rising enthusiasm for them as candidates. Their recent joint interview on CNN helped demonstrate they had suitable qualities as candidates and were serious people who had thought through things and could be national government leaders.

But, so far, at least, there is not enough evidence to show how well Harris can withstand the personal rancour in the withering onslaught that Trump has typically launched against his opponents. If she cannot pass that test, viewers may question how well she would do against other antagonists globally.

This writer will, once again, wake up at 3am on Wednesday morning South Africa time, a massive mug of espresso in hand and a reassuring, purring cat on his lap, to watch the debate in real-time to see just how well the two candidates do. And, crucially, to see if the outcome of the election rests on the way the two individuals comport themselves or demonstrate their ability or lack of it to rise to the challenge of this event. DM