Last month, the Democratic Alliance (DA) introduced a private members bill that proposes various amendments to the Prevention of Illegal Eviction and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act 19 of 1998 (commonly referred to as “the PIE Act”). Some of the proposed amendments, at face value, relate to technical, definitional aspects of the PIE Act, introducing caveats, extensions or exemptions to words such as “building or structure”, “unlawful occupier” or “reside”.

The real intent is however abundantly clear. As explained by the DA’s Shadow Minister of Human Settlements, Emma Powell — who introduced the members bill — it seeks to heighten the criminal sanctions for unlawful occupation of land, provide additional criteria for a court to consider in eviction cases to limit its application, and exempt the state from providing alternative accommodation when homelessness will result.

The proposed bill was supposed to be discussed in Parliament earlier this month but got postponed to discuss the Phala Phala debate instead. In the lead-up to Parliament's debate on the proposed bill (whenever this may be), I provide some thoughts, remarks and criticism of the DA’s move.

Illegal occupation and urban planning

The PIE Act gives effect to section 26(3) of the Constitution which guarantees the right to adequate housing and provides that no one may be evicted from their home without an order of the court and all relevant circumstances have been considered. The PIE Act was adopted in 1998 — just four years into democracy to address rapid urbanisation with the abolition of apartheid-era pass laws.

This unplanned urbanisation led to a mushrooming of informal settlements on the periphery of urban centres. As opposed to brutal forced removals, the PIE Act seeks to provide a fair and lawful way to evict unlawful occupiers in an effort to prevent the lawlessness that dominated apartheid-era forced removals.

Regrettably, the apartheid spatial context and violent evictions have not changed, which means that section 26 is also the most litigated of all the socioeconomic rights listed in the Bill of Rights, enabling the courts to develop rich jurisprudence on the state’s obligation to provide housing when an eviction leads to homelessness (even in a private eviction).

Criminalise or decriminalise?

The most important part of section 26 of the Constitution and the PIE Act — for the purposes of the DA’s bill — is that it decriminalised the unlawful occupation of land, repealing the apartheid-era “Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act 52 of 1952” (Pisa), and made the eviction process subject to a number of requirements necessary to comply with certain demands of the Bill of Rights. The question then is why would the DA want to return to the days of apartheid when access to land was often violently policed?

According to Powell, “the purpose of the draft bill is to prevent those who, in bad faith, occupy a property or land without any legal entitlement to do so and rely on the provisions of the PIE Act to either stay on a property for as long as possible or to try and get fast-tracked in the queue for low-cost housing projects.” In the explanatory comment, Ms Powell refers to this as “orchestrated and illegal land grabs.”

All this is problematic in so many ways.

The state has systematically failed to deliver housing

Firstly, the DA’s argument is premised on the notion that the millions of people waiting for housing must wait… patiently… for their turn… while the state… slowly… builds housing.

But we are close to three million households on the mythical waiting list. Many of these households are concentrated in the estimated 2,400 informal settlements nationally and millions of backyard residents. These amendments have a direct impact on criminalising the very people on the “waiting list”.

Housing delivery has declined over 20 years

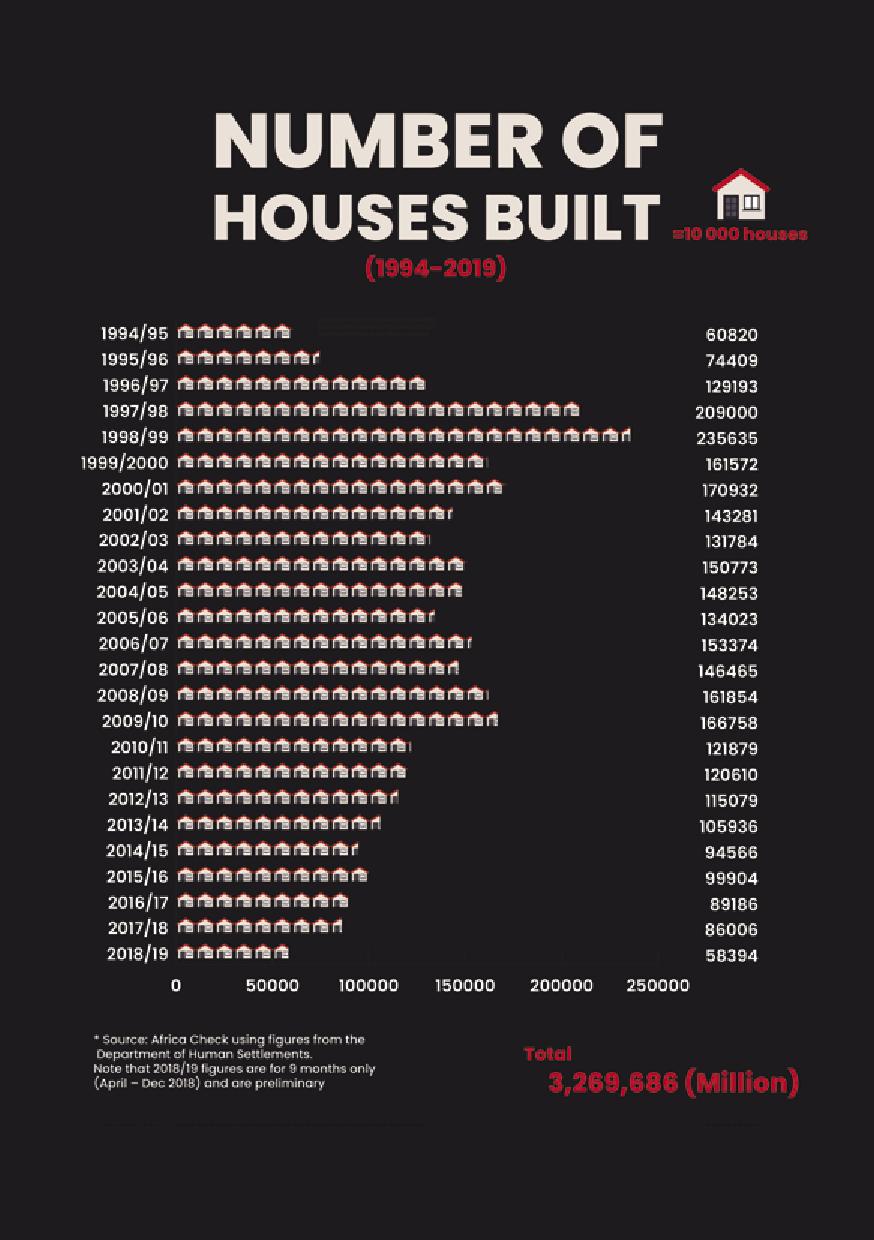

Secondly, one would think that criminalising unlawful occupation has merit if the state was actually delivering on their constitutional promises, but regrettably, the opposite has occurred with a steady decline in housing delivery over the past 20 years.

Taken from the International Labour Research and Information Group’s (ILRIG) South Africa’s Post 1994 Housing Policies and Budgets (Oct 2021)

Visit Daily Maverick's home page for more news, analysis and investigations

The track record in Cape Town speaks for itself — a failure to keep up with delivery nor provide any other alternative.

Is resorting to crimialisation justified? Under present circumstances of severe inequality and state failure, criminalising lack of access to land and housing (poverty, unemployment) is a cheap attempt to shift blame for the state’s systemic failure to the poor themselves. Where do they expect people to go?

No positive plan to address the housing crisis

Thirdly, the DA has not presented, in its history, a single bill that addresses the housing crisis. The City of Cape Town Human Settlements strategy, lauded to be a progressive document, still lacks any implementation plan.

Moreover, the notion that the state is using its land for the public benefit is completely misleading. Even parcels of land that were allocated for affordable housing since 2011 are still sitting vacant. In fact, the City of Cape Town alone owns hundreds of parcels of land (see here for map of City-owned land), but not even a single document addresses how the land will be used to address any imminent crisis — housing, transport, public space, amenities.

At a national level, the Department of Public Works is the custodian of 29,322 registered and unregistered land parcels, and 88,300 buildings.

Definitional changes

Fourthly, the definitional changes will lead to an abuse of power. The DA wants to ensure that the PIE Act only applies to unlawful occupiers who permanently reside in a hut, shack, tent or similar structure or any other form of temporary or permanent dwelling or shelter. The idea being that it shouldn’t be forced to get a court order if someone has not resided on land long enough to establish a “place of permanent abode” and “ordinary residency.”

Of course, these words are tremendously vague and open to interpretation. Is a four-walled structure with a bed, cupboards, kitchen utensils, and clothes more or less a home after five days or five weeks, for example?

What the DA really wants is the absolute discretion to decide how, and to whom, the law applies. Does this sound familiar to you?

If the intention of the bill, according to Powell, is to prevent “bad faith unlawful occupation”, then it wouldn’t matter what the structure looks like. What matters is that law enforcement authorities (Red Ants, Anti-Land Invasion Unit and others) have the power to dispossess and place the burden on the person being dispossessed to prove, after the fact, that their home (now demolished) was a home.

It is an impossible and absurd position to put any person in. It also reverses the intention of the PIE Act which was to ensure that courts decide what a home is based on evidence before the demolition occurs. The DA’s way is to subvert the judiciary whereas the PIE Act way is to uphold it, no matter its form.

Alternative temporary accommodation

The last notable amendment is that the DA wants to shorten the length of time needed to provide emergency housing to evictees. Over the years, temporary accommodation provided for by municipalities has become de facto permanent. However, the lack of affordable housing by the state or private sector (and also job opportunities) creates a bottleneck effect where occupiers have no other options.

In sum, it all boils down to whether the DA can have its cake and eat it too. It wants to criminalise the lack of housing, in a housing crisis, without having to fulfil its local government mandate to provide housing.

MP Emma Powell, do you not see the irony? It is clear that these amendments do not provide a solution. In simple terms, if you are landless or homeless you are essentially a criminal. The state is providing very limited housing in its problematic “waiting list”. DM