Most of my childhood was spent indoors, growing up in Johannesburg we moved from house to car to school, to car to mall, to car, to house. It was divided between my grandparents’ house in Alexandra township and several townhouses and apartments that we lived in, as well as stints in Boston, Massachusetts in the US and London, England.

Within all of that, my interaction with nature was limited. I have no memory of attempting to climb a tree in that spirit of gay abandon that children have, completely free within their bodies. There were no family vacations to the beach, or camping trips – my single mom had to work.

Author Serati Maseko playing on a sand dune. Image: Supplied

Author Serati Maseko playing on a sand dune. Image: Supplied

My play was a lot more imaginative and mental than physical: I played with dolls, my cousin and I made mud pies from sand and water and had tea parties, we played school-school and friend-friend, where we’d make-believe scenarios and act them out until my older cousin would have no choice but to ignore me in order to end the game.

While as an adult I developed a deep inner yearning to explore nature, I had no outlet for that desire, until I entered into a relationship with an avid nature lover who has exposed me to the joys and freedom of vast swathes of open spaces, frequent visits to the ocean where he holds my hand as I learn to become comfortable body-surfing wild waves, and dense, untamed bush with all manner of plant and insect life.

For the first time, I feel like I am developing a relationship with nature, and within that experience, I have come to discover how truly unacquainted I am with nature; compared with my partner’s ease and confidence in nature, I regard nature as threatening and unpredictable. It is not surprising given my lack of exposure to nature as something that I could play in and with as a childhood companion.

Sandton City during the Celeb City press conference at The Venue Green Park on 30 March 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Lefty Shivambu / Gallo Images)

Sandton City during the Celeb City press conference at The Venue Green Park on 30 March 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Lefty Shivambu / Gallo Images)

As I interrogated my own feelings of disconnect from nature, it made me question how much of it relates to the urban black experience.

While I wish not to make sweeping statements that homogenise the lived experience of all urban black people, it is worth interrogating the effects of urban and township life and lack of access to open green spaces, on how we relate to nature.

There are quantifiable effects of nature deprivation on human beings, so it is worth putting into context that masses of urban black people in South Africa have been denied access to open green spaces due to the Group Areas Act of 1950 (where black people were confined in open-air prisons called townships) and racialised violence in public parks.

A general view of the Alexandra township on June 02, 2020 in Alexandra, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images/Luba Lesolle)

A general view of the Alexandra township on June 02, 2020 in Alexandra, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images/Luba Lesolle)

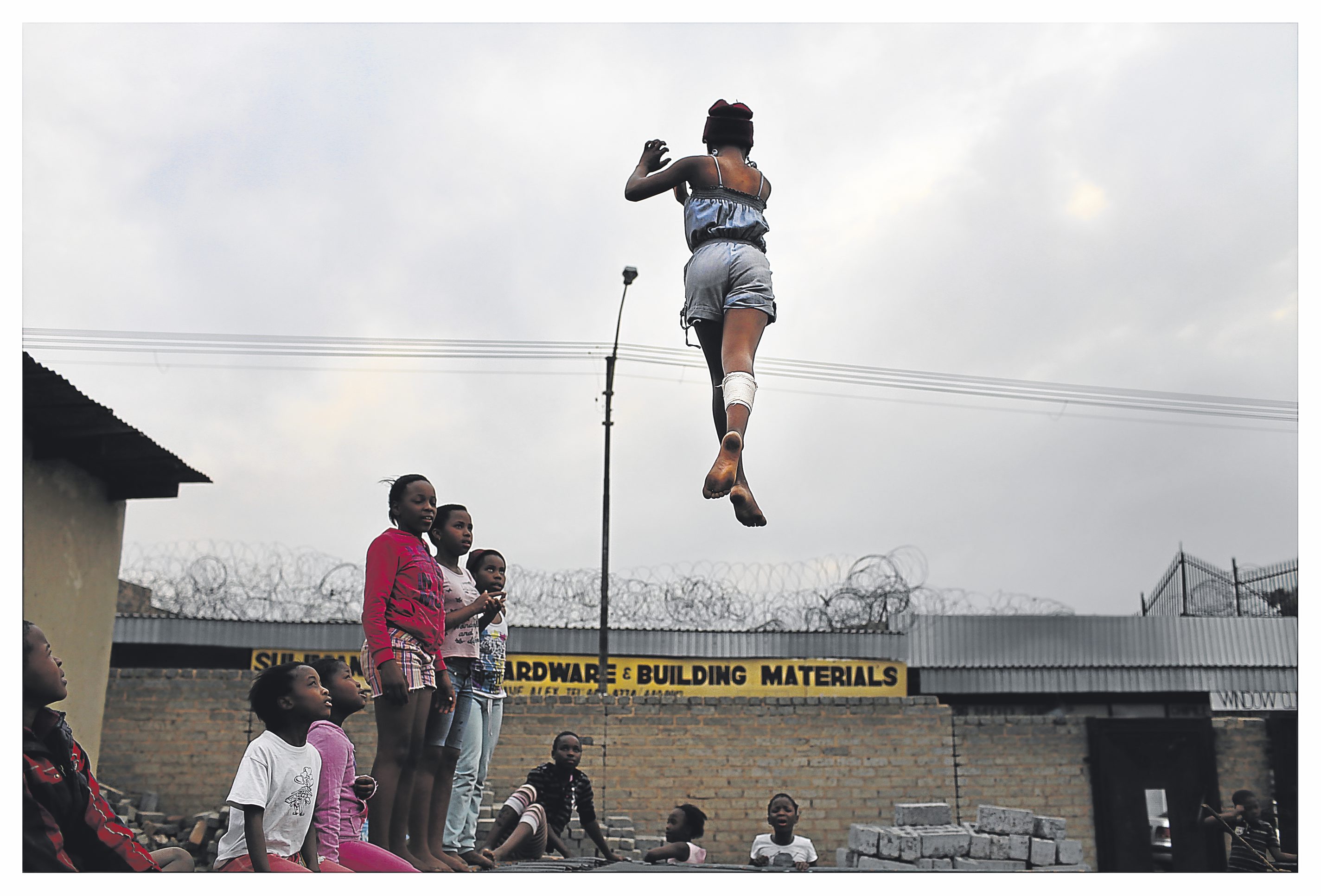

To reference Alexandra township, there are no spaces dedicated to children’s play, there are no parks, no greenery, no water features. The littered concrete street is their playground, and they dodge cars as though they were dodging each other in a game of tag. There is virtually no contact, no relationship, no interaction with open green spaces of nature for a child growing up in the township.

Interestingly, my grandparent’s house in Alexandra stands right opposite to a soccer ground, a fully equipped soccer ground with benches for spectators, and grass that is maintained and manicured; however, that ground stands mostly empty during weekdays when there are no soccer games, and while children play on the street, in narrow yards between the one-room houses, being shushed and yelled at for making a noise.

Children in the township learn early that there is no space for them. This is not limited to the South African context: historically oppressed and marginalised people, of which black and brown people form a major part, living in urban areas in Western countries such as the US and UK, are more likely to be living in the inner cities and ghettos which are characterised as densely populated, having inadequate municipal services and often lack of accessible parks and green open spaces.

The Johannesburg skyline is seen in the distance as visitors to an amusement park enjoy a ride one day before the Confederations Cup kicks off on 13 June 2009 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Kevork Djansezian / Getty Images)

The Johannesburg skyline is seen in the distance as visitors to an amusement park enjoy a ride one day before the Confederations Cup kicks off on 13 June 2009 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Kevork Djansezian / Getty Images)

Multiple studies have been done on the effects of nature deprivation in urban spaces. The lack of access to green spaces of nature is proven to contribute to higher rates of crime and violence in communities, depression, attention deficit disorders and a host of other mental and physical health issues. This is further compounded by the fact that people living in lower-income areas are disproportionately affected by pollution – for instance, townships are often located near major sources of pollution such as mine dumps and sites of open waste burning. Communities that have more green space are linked to fewer requests for antidepressants, lower instances of panic attacks and anxiety, higher IQ in children, longer lifespans – the list is endless. Importantly, a lack of access to nature also contributes towards a feeling of apathy towards the conservation of nature and the environment. You cannot care about what you do not have a connection to, or benefit from.

This growing sense of separateness from nature that comes with our rapidly developing world, and an inequitable access to open green spaces, has far-reaching consequences, and it is no mistake that it is concurrent with the rapid degradation of our environment. Access to open spaces of nature and biodiversity cannot continue to be a privilege of the individual based on economic status; it needs to be valued as an integral part of a healthy society. It is important that we engage in the process of democratisation of nature as a place of leisure, rest and play, not only to prevent the multiple effects of nature deprivation on our psyches, physical bodies and our communities, but for the urgent issue of the preservation of our environment and our planet. DM/ML

Serati Maseko is a South African singer-songwriter, performer, poet and writer.

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA - JUNE 13: The Johannesburg skyline is seen in the distance as visitors to an amusement park enjoy a ride one day before the Confederations Cup kicks off on June 13, 2009 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo by Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images)

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA - JUNE 13: The Johannesburg skyline is seen in the distance as visitors to an amusement park enjoy a ride one day before the Confederations Cup kicks off on June 13, 2009 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo by Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images)