Entrapment in the land of Kafka

“How does the order work, what do you need me to do?”

Around two minutes into the seven-minute telephone call, the supplier asked the pivotal question. Up until then, in a conversation that never pretended to be anything other than what it was, the two men had been feeling each other out. They already knew each other’s names so it clearly wasn’t the first time they’d spoken — the supplier was “Andre” and the inside Eskom man was “Gerald” — but now was the moment to get into the details of the scam.

“They’re gonna send you an RFQ,” said Gerald, referring to a fundamental item in Eskom’s procurement system, the request for a quotation. “The RFQ will give you the scope of work.”

Apparently, thanks to Gerald, Eskom already had a vendor number for Andre’s company, which was linked to the CSD, the central supplier database overseen by National Treasury. What Andre needed to do next, explained Gerald, was send Eskom a quote, which would generate an order.

“And then after that you buy the stuff you need to supply, and then you supply Eskom. After you supply, you invoice Eskom. They will pay you 14 days after invoicing.”

“Okay,” said Andre, “but what’s in it for me? How am I going to score out of this?”

“Sorry?” responded Gerald.

“I mean, how much is for me? How much money can I make with this?”

“Per order, you will make R300,000.”

“And what’s it gonna cost me?”

“To buy the stuff… R150,000.”

“So I make at least R150,000 per order, profit?”

“No, no, no, profit is R300,000.”

“That’s money,” said Andre, impressed. “That’s money.”

“Ja,” Gerald said. “Per order. The total order value, né, will be R800,000.”

And so, at last, Andre was getting the full picture. Although he would only lay out R150,000, which was the price of the actual consignment, he would put in an order for more than five times that amount, which Gerald would push through the system. From the total R800,000, Andre would keep R450,000. The remainder, a further R350,000, would be split between Gerald and his line management.

“Yes,” explained Gerald, “because you must also take care of the other players. You must take care of the procurement manager and stuff like that, you agree?”

As it turned out, Andre agreed wholeheartedly. He asked Gerald when they could begin. The answer, according to Gerald, was by the end of the week.

[video mp4="https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/WhatsApp-Audio-2023-09-20-at-13.28.50.mp4"][/video]

This illuminating sound clip, a confirmed “entrapment” by contracted Eskom security, was dated 17 February 2022. It was provided to Daily Maverick in mid-July 2023, by a former senior executive of the power utility who — like all of the sources for this story — insisted on remaining anonymous. The requests for anonymity aside, though, the sound clip’s value was held in what the Eskom media desk had to say (or not say) about its highly charged contents.

“Eskom bears no knowledge of the sound clip nor knowledge of the personnel who may have allegedly recorded such conversation,” Daily Maverick was informed. “Eskom is therefore not in a position to authenticate the sound clip in question given that no sufficient information was provided to verify. However, given that the conversation appears to have an element of corrupt behaviour, Eskom would like to be furnished with more information that could assist to initiate an investigation.”

It was, in hindsight, not just a perfectly circular evasion, but a perfect metaphor for Daily Maverick‘s months-long investigation into the murky and often illogical world of Eskom’s “informal” or “low-value” procurement systems — in other words, the systems that, since 2010 at least, had been governing all purchases below R1-million.

By the estimate of one of our multiple sources, the holes in informal procurement were costing the South African taxpayer in the region of R300-million per month. But for us to establish the veracity of this enormous estimate, Eskom would have needed to take seriously the 23 pages of questions that we had sent.

Instead, after three weeks’ grace — including the two full weeks that, according to the Eskom media desk, the questions had been languishing in their “junk” folder — half a page was all we got back.

We were, to risk the cliché, way out in the land of the Kafkaesque: a land that Merriam-Webster had long ago defined as one of “bureaucratic delays” with a “nightmarishly complex, bizarre, or illogical quality”.

And nowhere, it seemed, was this more true than in the responding paragraph on the sound clip.

For starters, to reiterate, the original source of the clip — as confirmed by Daily Maverick — was a private security firm under contract to Eskom in February 2022. Had all institutional memory been erased in less than 18 months?

Then there was the fact that the Eskom media desk, in response to our request for verification, had asked us to verify the evidence in return. Other than a copy of the audio file itself, what “sufficient information” could they possibly have wanted? Finally, there was the implicit suggestion that no action would be taken unless Daily Maverick “furnished” said information. Was the rooting out of “corrupt behaviour” our job or theirs?

Like the ambidextrous non-response, these hypotheticals appeared to collapse in on themselves until right was left and left was right. If the stakes weren’t the rolling blackouts that had been dropping the economy into freefall, we might have turned on our heels and followed the breadcrumbs back to sanity. But the stakes were an economy in freefall, and on this score, the entire country seemed to be waging a losing battle with sanity — and so, to remain counter-intuitively sane, we walked on into the darkening forest.

Also, as with any tale worth telling, we had a strong light to guide us. This was in the form of a whistle-blower who, up until 2021, held a pivotal position in Eskom’s procurement division. We would never know the whistle-blower’s name, we wouldn’t even know the whistle-blower’s gender, but what we would come to know — after testing and retesting the evidence — was that we were being fed the truth.

For all of their evasions, the Eskom media desk did not dismiss any of the whistle-blower’s evidence as fake.

Ghost buyers, duplicates and quadruplicates

At any point, if Eskom had wanted to establish the identity of Gerald — for the purposes, say, of bringing charges against him and sending a strong message to the organisation about the consequences of procurement corruption — it should have been a relatively easy thing to do.

From his or her encrypted Proton email address, our whistle-blower sent us dozens of mails explaining how the system was supposed to work. In one of these mails, there was a sentence that summed it all up:

“The traceability behind all of these interesting purchases can be linked to the PR number, RFQ number and/or the PO number. Together with the PGr (buyer role), the history should be there.”

Put another way, for every item below R1-million that Eskom procured, there were supposed to be unique codes attributed to the purchase request, the request for a quote and the purchase order. More importantly, though — particularly when it came to tracing corruption — there was supposed to be a unique code for each individual Eskom buyer, known internally as the “PGr” or “purchasing group role”.

Theoretically, then, even if Gerald hadn’t yet entered the PR number or RFQ number, he had (by his own admission in the sound-clip) created a vendor number for Andre’s company — it was simply a matter of matching this with Gerald’s unique PGr.

Still, to demonstrate the gap between how things were supposed to work and how things actually worked, our whistle-blower had already provided us with a trove of screen grabs from the procurement system itself.

For Daily Maverick, from the very beginning of the engagement, this had been akin to journalistic gold — since late 2022 we’d been chasing down exactly this type of evidence, but our requests under the Promotion of Access to Information Act had yielded no results.

Now, however, we were in the belly of the proverbial beast — and, from the first screen grab, it was looking somewhat dark.

The screen-grab was attached to an email with the subject line “Eskom Procurement: ‘Ghost’ SAP Buyer Roles” (see “Figure 1” below).

As a leading global software solutions provider, we soon discovered, SAP had awarded Eskom its prestigious “Advanced Centre of Expertise” certification in 2016, which meant that the power utility was the inaugural recipient of this honour on the African continent. But, if the evidence was to be believed, Eskom’s use of the SAP software was far from praiseworthy.

“Please see below some SAP buyer roles via which buyers procured goods/services through the SAP system,” our whistle-blower explained, before pointing out that Eskom staffers had been “fraudulently… hiding behind these ‘ghost’ vehicles to procure whatever.”

As to why these vehicles were characterised as “ghosts,” the whistle-blower was explicit:

“The buyer group (i.e. PGr) should have an actual person’s name and surname (the standard way of creation) and should be unique (one-to-one relationship) to a specific person's identity (in procurement). This was taken in 2020 and these roles have most definitely made purchases.”

What we were confronted with, to be clear, was a long list of “PGr” codes without any name or surname. The implication, of course, was that if there was any corruption, it would be impossible to trace to a particular Eskom staffer. And equally obvious, the only way for Daily Maverick to establish whether the ghosts in the screen-grab had actually made purchases was to put the question directly to Eskom.

We also wanted to know from the power utility whether it was aware of the problem of ghost buyers in general and, if so, how many had been identified on the SAP system and what corrective steps had been taken.

But among the many questions that the Eskom media desk chose to ignore, these few were just the start. Further down in our 23-page list of questions, we sought similar answers when it came to screen grabs that contained further evidence of defiance of the same critical rule.

For instance, the screen grab that displayed confusion and inconsistency in buyer group roles, with a total of 1,340 entries that had apparently been uploaded at random — here, the names of individual buyers appeared above or below the names of Eskom power stations and even entire Eskom divisions, such as generation and transmission, which each had their own purchasing group codes (see “Figure 2”).

And true to form, in the following three screen-grabs, the same pattern emerged. First, there was a screen grab that demonstrated a dozen purchasing group roles with the entry “do not use” below inconsistent name entries (see “Figure 3”); then there was a screen grab with misspelt town names, an entry titled “avoid this one” and a single purchasing group role for both the Medupi and Kusile power stations (“Figure 4”); and finally, a list of 15 names that had been duplicated, meaning that each of these Eskom buyers had two unique purchasing group codes (“Figure 5”).

In our request for comment from Eskom, to establish our bona fides, Daily Maverick included copies of all the supplied screen grabs. Why, we asked, had power stations and even entire Eskom divisions been assigned their own purchasing group codes? What was the explanation for entries such as “do not use,” “avoid this one” and “Medupi and Kusile”? Was there a valid explanation for the duplication of names and, if not, had Eskom initiated an internal investigation into the 15 duplicate buyers?

Again, however, we were met with silence.

And so bringing it all back to Gerald, the Eskom staffer from the sound clip, what should have been and what in fact was were clearly worlds apart — if “ghosts” could appear in the SAP system, if buyers could be so easily duplicated, what chances were there of bringing the perpetrators of corruption to book?

As for Andre, the private security contractor who was posing as an Eskom supplier, even if he was a genuine vendor the same principle would have applied. Because, it appeared, the duplication of names was a problem that extended across the entirety of the SAP system — our whistle-blower, after sending us the various buyer screens, had sent us a pair of screen grabs that demonstrated the pattern as it applied to Eskom’s vendors.

The difference here was that some of the suppliers were entered into the system as many as four times (“Figure 6”). And significantly, as our whistle-blower noted with respect to the second screen (“Figure 7”), what Daily Maverick was seeing was just “a small selection of the 10,000-plus Eskom vendors”.

“Same vendors, different vendor numbers,” the whistle-blower commented. “Is this not the outcome of a corrupted and weakened SAP system?”

Back to the (not so) basics

It was a question, by this point, that had been comfortably answered. And it led, seamlessly, to the next: who, or what, was to blame?

Perhaps it would have been better not to ask. Because, once more, it was the qualities of the Kafkaesque — the “nightmarishly complex, bizarre and illogical” — that were implicit in the details.

According to the whistle-blower, the core problem with Eskom procurement could be traced to the “Back-2-Basics Programme,” an R8.5-billion project that had been initiated in 2010 to improve and streamline Eskom’s service tools, operations, maintenance and engineering.

At the very start of the engagement with Daily Maverick, in fact, the whistle-blower had expressed “bewilderment” that nobody had yet properly investigated the role that the B2B programme had played in “ruining Eskom”.

To us, at first, this was a surprising allegation, particularly since the same email had acknowledged the B2B programme as an “intelligently crafted” initiative that had been launched with “good intentions”. And yet, the whistle-blower informed us, it was “common knowledge” at Eskom that the programme’s PCMs — or process control manuals — had been routinely ignored for years.

Here, we were referred to a document officially identified as “32-1034”. Signed on 1 July 2019 by four senior-level Eskom staffers — including the chief procurement officer at the time, Solly Tshitangano, who less than two years later would be found guilty of serious misconduct by a disciplinary inquiry — the document was relatively easy to locate, and contained exactly what the whistle-blower said it would.

Titled “Eskom Procurement and Supply Chain Management Procedure,” its 213 pages held detailed instructions on the utility’s entire buying process, which — as was made clear in a box on page 37 entitled “Revisions” — had been relaunched in October 2010 by the same B2B programme highlighted by our source. It was the contents of pages 23 through 36, however, that shone the spotlight on the opportunities for institutional corruption that had been suggested by the sound clip and the screen grabs.

In essence, with the assistance of contracted private sector consultants and lawyers, the current Eskom procurement process had been drawn up to include a set of checks and balances that required oversight and sign-off by all relevant line managers and cross-departmental teams.

While this made perfect sense at the start, by 2019, after four revisions, the “Authority to Execute” had expanded to a total of 22 sub-categories, from the chief procurement officer at the top to the end-user and LPO (local purchase order) buyer at the bottom, with the Eskom board, group taxation department, RG&C (risk, governance and compliance) department and P&SCM (procurement and supply chain management) contract department all playing roles.

Added but not limited to this, the EIO (Eskom information officer), SDL&I (supplier development, localisation and industrialisation) department and SRC (supplier review committee) had also been assigned inputs.

How would all of these managers, employees and departments co-ordinate their various activities to ensure a streamlined process with minimal overspend and corruption?

On this point, document 32-1034 referred to the “Process for Monitoring,” which contained 15 sub-categories. Overseen by the Public Finance Management Act and the attendant responsibility of the Eskom board, this section had clearly been drafted to caution employees about the barriers to (and consequences of) misconduct.

Under the “Ethics” sub-category, there was the injunction to attend training on the “Conflict of Interest Policy” and the linked obligation to declare such interests in direct reports. Then, as in the rest of the document, there was the raft of acronyms — the forms that had to be completed by all members of the CFT (cross-functional team); the probity checks that had to be performed on all PTC (procurement tender committee) and DTC (divisional tender committee) members; the evidence of compliance with SHEQ (safety, health, environment, quality) requirements that had to be provided by certain suppliers; the irregular expenditure framework issued by NT (National Treasury); the requests for condonation of irregular expenditure that had to be signed off by the relevant DAA (delegated approval authority).

On it went: there was the ETC (Exco tender committee) and A&F (assurance and forensics); the ERAs (execution release approvals) and NDAs (non-disclosure agreements); and, most bizarrely, the fact that “all condonation requests,” before submission to the relevant DAA (see above), had to be “signed off by the relevant GE/DE/GM PED/GM ERI [group executive/divisional executive/general manager primary energy department/general manager Eskom Rotek Industries SOC]”.

The last phrase, to be clear, was an actual quote from page 32 of the all-important document 32-1034. By Daily Maverick‘s reckoning, it underscored the fact that every employee of Eskom who had been recruited in a role that had anything to do with procurement — a number that our various sources estimated at more than half of Eskom’s 42,000 employees — was required to negotiate a table of acronyms that totalled more than 120 entries.

More than that, though, the acronym-heavy phrase gave credence to our primary source’s allegation that Eskom’s procurement processes had become irrelevant to most staffers — far from stamping out corruption, it seemed, the layers of cross-departmental oversight and the complexity of the system were abetting enterprise-wide malfeasance.

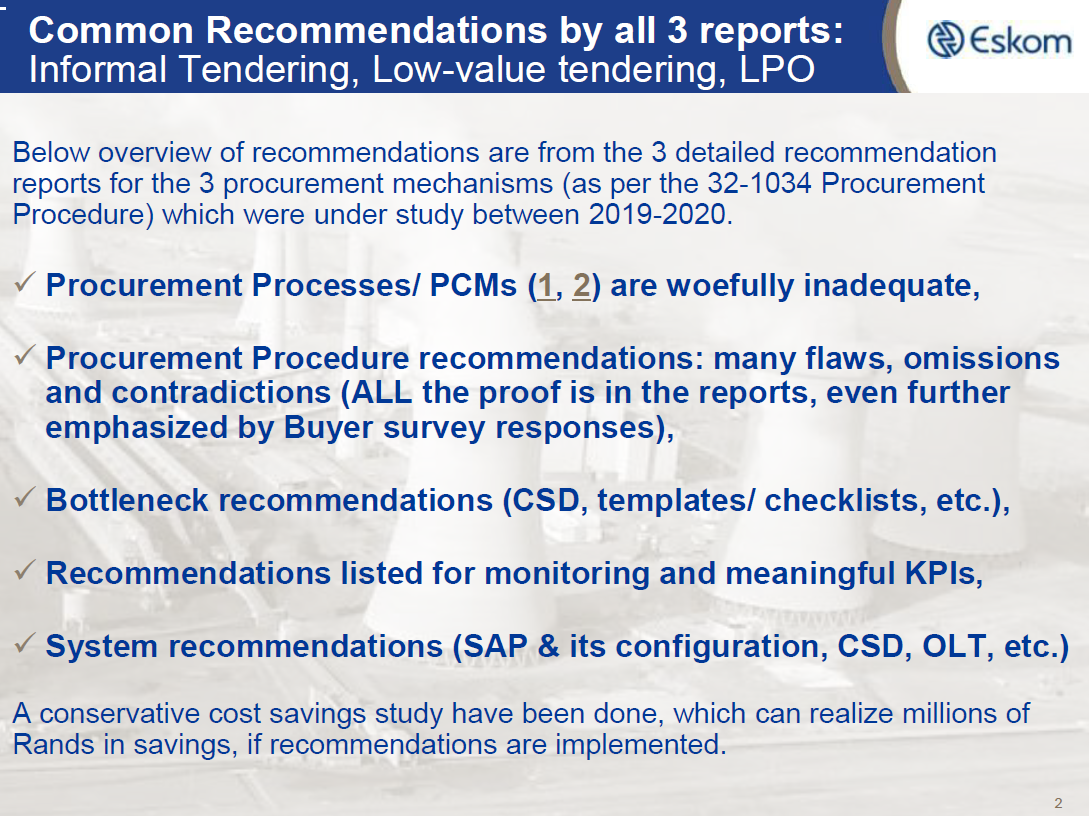

The dilemma, according to the whistle-blower, was well-known to Eskom’s principal stakeholder, the Department of Public Enterprises. In fact, as confirmed by Daily Maverick, back in 2019 there were recommendations made by a ministerial task team to improve the procurement processes, with internal Eskom working groups assigned to take on the task.

A slide from a presentation by one of these working groups to senior Eskom managers at the time was provided by the whistle-blower, along with the allegation that “nobody seems to want to take ownership of the good recommendations made thus far”.

Obviously, what we would have liked to know from the Eskom media desk was, firstly, whether it was true that nobody had taken ownership of the working groups’ suggestions, and, secondly, whether the procurement processes were still (as per the slide above) “woefully inadequate”.

Treasury and grass-cutting services

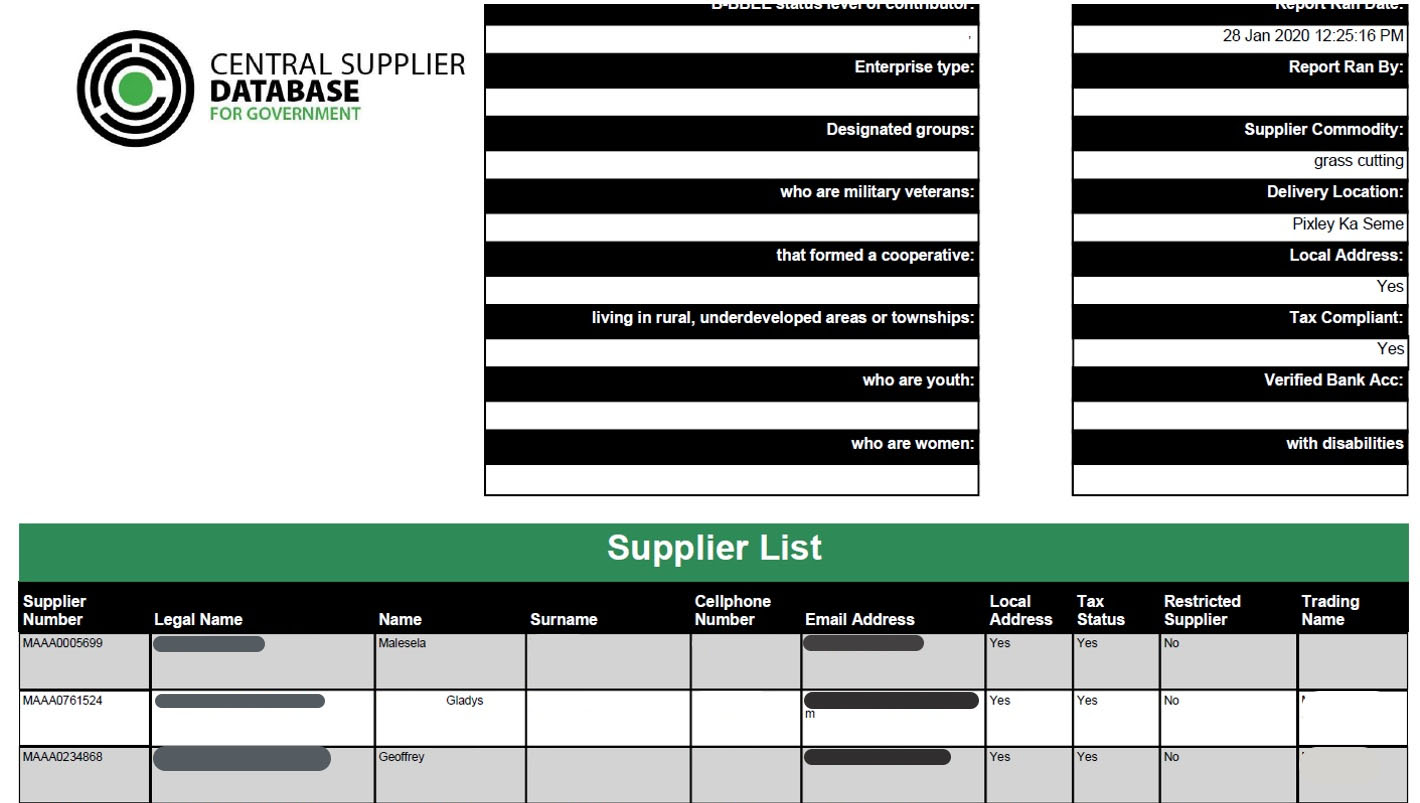

But Eskom’s silence notwithstanding, we had yet to focus on another pivotal screen grab provided by our whistle-blower. And this critical piece of evidence, since it exposed the holes in the CSD — or central supplier database — as overseen by National Treasury, brought an even deeper layer to the explanation of why the system was not functioning.

In the email outlining the context, our whistle-blower referred to the informal tendering instructions that compelled Eskom buyers, once a requisition or “need” was established, to search for the goods or services on the CSD.

“Once a list of potential suppliers/vendors was populated at the bottom of the screen,” the whistle-blower noted, “the buyers were forced (from instructions, procurement policy) to request for a quote (RFQ) from the first three or 10 suppliers (the procedure and instruction note/s were still contradicting on the number in 2021/22). In below case, the buyer was forced to get a quote from ‘Afrika Crime Solutions’ and ‘Metsing Cartridge’ for grass-cutting services!?!”

The whistle-blower continued that “based on the lowest price and the BBBEE levels, the purchase order [PO] was awarded.”

These criteria, he or she explained, and “the fact that buyers were, up until 2021 at least (still are?), required to use the CSD database, is one of several reasons why Eskom is still paying large amounts of money for… knee guards, toilet paper, milk, mops etc (as it falls under R1-million, and hence requires the informal tendering process to be followed)”.

Again, Eskom’s media desk was afforded the opportunity to respond to each of the allegations in turn. Had either Afrika Crime Solutions or Metsing Cartridge been awarded a contract to cut the grass at one of Eskom’s facilities? Was the RFQ in the CSD applicable to the first three suppliers or the first 10 suppliers? Were Eskom buyers currently required to use the CSD? Had Eskom put any corrective measures in place to deal with the informal tendering process as it applied to the CSD?

It was the knee guards and mops question that may have guaranteed the non-response, however, because back in 2021, when former Eskom CEO Andre de Ruyter discovered that the power utility had been paying R80,000 for knee guards that could be bought for R100 at any local hardware store, he informed News24 that “Eskom did not have a catalogue of goods, suppliers or spending limits to work with, instead relying on ‘free-text procurement’.”

In other words, aside from the alleged holes in the CSD, corruption in the informal or low-value tendering space was apparently also being facilitated by the fact that — according to De Ruyter — officials could buy goods at prices they had “determined themselves”.

Still, when it came to the CSD-related questions, we had a long-shot chance at some answers. Since both of the contact people that had been listed in the CSD for Afrika Crime Solutions and Metsing Cartridge squared with the information we obtained from a companies’ director search, we also put the relevant questions to them. Had either of these companies provided grass-cutting services to Eskom? If not, did the respective directors have any idea how their companies — which on the face of it appeared to be part of the security sector — got flagged as preferred suppliers?

To our surprise, the answers were forthcoming almost immediately. Malesela Mosuwe, the sole director of Afrika Crime Solutions, denied that he had ever provided the service to Eskom but informed Daily Maverick of the following:

“Concerning grass-cutting, all I know [is that the] commodities list is available for any potential supplier to choose on [the] CSD. It doesn’t discriminate on anything to do with company name.”

Geophery Mithileni, Metsing Cartridge’s director, stated simply that his company had “never rendered any service [to] Eskom.”

It all came down, then, to National Treasury — and before approaching them for comment, Daily Maverick felt it was prudent to first confirm the duties and obligations of the government department in terms of the applicable legislation.

Here, the all-important document was identified as “32-1033” — the accompaniment to 32-1034 — which had also been signed on 1 July 2019 by the same four individuals as above. At only 13 pages, this document was the “policy” to its sister document’s “procedure” and it explained in full the legislative environment that governed all items procured by employees of the utility.

For a start, noted document 32-1033, Eskom — as an “organ of state” — had since 1996 been legally obligated, under section 217 of the Constitution, “to create and maintain an enabling procurement system.”

Accordingly, the document continued, the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act (PPPFA) had been passed in 2000 to give effect to section 217, by implementing “standardised tendering (bidding) processes in the procurement of goods and services by organs of state.” As such, the PPPFA had also been “intrinsically linked” to the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA), promulgated in 1999.

The sole exemption to the above, stated document 32-1033, was “with respect to procurement authorised by Development Funding Institutions (DFI’s).” Then, after laying out the significance of the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act of 2003 and its attendant “Regulations” of 2016, the Eskom policy document arrived at a “normative” list of 37 items that demonstrated the behind-the-scenes heft of National Treasury.

There were four items in document 32-1033 that highlighted the centrality of the latter: the National Treasury Regulations, the National Treasury Standard for Infrastructure Procurement and Delivery Management, the National Treasury Instruction Notes and Guidelines and, finally, National Treasury Instruction Number 02 of 2016/2017, which dealt with “cost containment measures”.

With this knowledge, Daily Maverick could refer back to the “Revisions” section of document 32-1034 (the “procedure” directions, page 37), which stated that the B2B programme had been updated for a third time in March 2018 to “align with” the National Treasury Instruction Notes and Guidelines.

In all, National Treasury was mentioned almost 70 times in document 32-1034, with a clear emphasis on the requirement in the informal tendering process (page 146) for the “issuing of a RFQ to the prescribed number of potential tenderers found on the CSD.”

So what did this department, the very same institution that had long been responsible for managing the nation’s collective taxpayer funds, have to say in response to Daily Maverick‘s questions?

“Thank you for the media query,” the department informed us. “We note that you indicate that you have already sent the query to Eskom as well. They are best placed to respond.”

Outages and maintenance

We were descending ever down, it seemed, into the Kafkaesque.

Because what it all meant for the citizens of South Africa, according to our whistle-blower, was not just random and exorbitant spending on items that had little or nothing to do with Eskom’s core function, but also massive and entrenched inefficiencies when it came to the functions that the power utility had been mandated to perform — for example, the scheduled and urgent fixes on its ageing fleet of coal-fired power stations.

With respect to this perennial challenge, in a series of internal Eskom emails that the whistle-blower shared with Daily Maverick, the CSD of National Treasury remained front and centre.

“At Eskom,” noted our whistle-blower by way of introduction to these emails, “there is a total disconnect between the processes and the various enabling tools (SAP, CSD, etc).”

From the contents of the correspondence, the point was difficult to dispute.

On 16 October 2019, an email was sent from an Eskom manager to two staffers and cc’d to another 10 staffers (see “Email 1” below; due to the inherent safety risks, the names of all the senders have been excised from the appended mails).

“We have a number of challenges with the CSD system,” the first email began, “and the [instruction] related to issuing RFQs to feeder areas local to the [power stations]. These issues are hampering our task, [are] leading to unhappiness in the communities local to the power stations and are [creating] risks of not having spares available when required.”

In a string of bullet points, the manager then laid out the various problems, beginning with the observation that suppliers were uploading addresses onto the CSD “for all areas local to every power station” — which, of course, had resulted in Eskom approaching suppliers that were “not physically living or operating in the area.”

As large of a system leak as this point evinced, however, it was the second bullet point that echoed and affirmed one of our whistle-blower’s primary allegations: “The CSD commodity list is not aligned with Eskom commodity lists. This results in the buyer not always approaching the right suppliers or… missing suppliers that are in fact qualified to supply.”

The next point drilled deeper into the dilemma, noting that “the majority of local suppliers” had not been registered on Eskom’s database, which was causing delays in the placement of orders and posing the risk that power stations would not get the necessary spares.

As an example, the manager referred to the town of Pullens Hope next to the Hendrina power station in Mpumalanga, where there were around 38 suppliers registered on the CSD but only four on the Eskom database.

Finally, after noting that non-operational suppliers were not deregistering from the CSD, the manager pointed out that there was “no mechanism” to confirm that a supplier was in fact qualified to deliver certain items.

A week later, on 23 October 2019, a similar internal email was sent to an entirely different set of Eskom staffers, from an entirely different manager — this time, the concerns were specific to what was known as “Gx,” shorthand for the generation division (see “Email 2” below).

“The issues with the CSD database are not going away,” stated the manager. “It is becoming more of an issue.”

There were two primary concerns, according to this particular manager, the first to do with “engineering” — where, again, vendors were being registered on the database without proper vetting — and the second to do with “process” — where something called “practice note 2” was identified as the glitch in the system.

So what was ‘practice note 2’?

Helpfully, the whistle-blower provided us with an internal email from three months before (9 July 2019) that had laid it all out (see “Email 3” below).

Under the subject line “Procurement challenges,” the manager (a different individual to the two above) clarified that it was a “policy upgrade” from document 32-1034, which had only just been signed off as official Eskom procedure.

“Respectfully (and in my personal opinion),” the manager began, “these policy upgrades are not going to assist us as procurement practitioners to render a more effective service to your stations.”

Clearly, then, the recipients of this email — who numbered a dozen in all — held positions of authority at Eskom’s fleet of power stations. And what they were now being told was that a certain revision in document 32-1034 was about to make their jobs a lot more difficult.

“The new revision requires buyers to go to the first 10 names on National Treasury’s Central Supplier Database,” the final paragraph explained, “if only one response is received, the enquiry must be cancelled and re-issued…”

As far as Daily Maverick was concerned, the whistle-blower’s allegations had now been comfortably corroborated — the B2B programme and its various revisions, far from stream-lining the core tasks faced by the honest brokers in Eskom procurement, had all but rendered the tasks unachievable.

Zeroes and anti-heroes

Still, in terms of circular evasions, nightmarish complexity and general illogicality, we hadn’t yet bottomed out.

In the second of the three paragraphs that we received in response to our 23 pages of questions, the Eskom media desk told us the following:

“In as much as Eskom can authenticate some e-mails, unfortunately due to the lapse of time it is not able to authenticate… the information on the screen-grabs. Eskom would also like to highlight that CSD is a National Treasury system that applies to Eskom as per the National Treasury Instruction Note 4A of 2016/17.”

How to read this?

While “some” of the internal Eskom emails were accepted as authentic, we were not told exactly which. Also, although Eskom did not dismiss any of the screen-grabs as forgeries, it used the “lapse of time” argument to avoid deeming them genuine — thereby overlooking, perhaps, the fact that it was admitting to an inability to access historical data on the SAP system. And lastly, what was the point of mentioning the instruction note of National Treasury? Were we being informed here that Eskom’s hands were tied?

But the most glaring logical conundrum was this: if “some” (i.e., at least two of the three) internal emails were acknowledged as real, didn’t that speak to the legitimacy of the source in general?

Clearly, the whistle-blower had no problem accessing the historical data.

In this regard, aside from the internal emails and the screen grabs, we were provided with a series of spreadsheets — directly exported from the SAP system — that demonstrated, from the earliest years of the B2B programme, how taxpayers’ funds had been put to questionable and practically un-auditable use.

Back in March 2011, for instance (see “Spreadsheet 1” below), an individual staffer with the purchasing group code “346” had spent R975,000 on either 1,500 or 1,5-million envelopes — it wasn’t transparent from the SAP data how many envelopes had actually been purchased. What was transparent, however, was that R800,000 had been spent on A4 envelopes and a further R175,000 on A5 envelopes, the latter adorned with Eskom’s logo.

The problem of irregular zeroes — in other words, where the quantity of the item multiplied by the value per item did not match the total spend — was repeated further down in the same spreadsheet, when it came to a total spend of R805,000 on a combined purchase of golf shirts and golf caps in September 2011.

Was it 5-million caps and 4.95-million shirts, as it stated in the spreadsheet, or 5,000 of the former and 4,950 of the latter, as would have made sense from the calculations? Moreover, even if it was the latter, how did this fit with Eskom’s core deliverable, which was no more and no less than keeping the lights on?

Ironically, the very same spreadsheet contained a line item from June 2011 for the printing of B2B training manuals, which listed 1,000 manuals at a value of R3-million per item for a total value (again the calculation problem) of R3-million.

By Daily Maverick‘s reckoning, there were very few examples from this particular spreadsheet that made any sense in the broader context.

And over the next eight years, as evidenced by a different spreadsheet (see “Spreadsheet 2” below), the situation would show no signs of improving. In August 2015, for example, three exorbitant requisitions for “emergency food” would be entered by a buyer with the purchasing group code “840” — in a matter of weeks, the purchase orders would all go through, despite the fact that all three quantities were listed as “1,000” while both the values per item and total values were listed as R124,000, R135,250 and R124,000 respectively.

Equally inexplicable was the fact that this particular spreadsheet, which contained only a dozen line items, showed requisition dates — in random order — from 2011, 2012, 2015 and 2019. And if the dates on the SAP spreadsheet made no sense, the bunching together of purchase categories made even less sense: aside from the “emergency food” purchases there were purchases for “alcohol testers,” “additional sockets for gym” and a grouping of three purchases, made over two days in April 2019 by two different purchasing codes, for a total of R2.069-million in “grass cutting services”.

Did the spend on grass-cutting services have anything to do with the screen grab above from the CSD? Again, because of the inconsistency and corruption in the system, it was impossible for Daily Maverick to tell.

What we could tell, however, was that the information in this latest spreadsheet wasn’t an anomaly. A third spreadsheet from the SAP system (see “Spreadsheet 3”) showed the exact same pattern — i.e., the entry of random dates stretching in no particular order from 2011 to 2019, with neither rhyme nor reason on the categories.

Here, an entry of R29.48-million for “consultant services” — which, firstly, should have been categorised as a “formal tender” and, secondly, held no information on the name of the consultancy nor on what the services were for — appeared directly above eight separate entries (on the same day, in August 2019) for vegetable orders from McCain’s at a total of R295,650.

To fix or to remain forever broke

During our months-long effort to triangulate and verify the whistle-blower’s evidence, Daily Maverick approached a number of sources that could justifiably claim an intimate working knowledge of Eskom’s procurement systems. None of them, it turned out, was particularly surprised by the evidence; by their combined assessments, the leaked screen grabs, emails and spreadsheets were all genuine.

But, again, all of the sources referred to the risks if their names were revealed.

Given recent news reports of an alleged hit on an Eskom whistle-blower, their reticence was understandable.

As for our own whistle-blower, when we requested a meeting at a secure location of his or her choice, the response was apologetic yet firm.

“I totally understand where you, your editor and Daily Maverick is coming from in terms of the request,” we were told.

“I will unfortunately need to decline the meeting. I do humbly apologise. I need to protect myself and my family, given that there are forces at play, like you rightly mentioned.”

Whoever these forces were, while Daily Maverick was convinced of the underlying reality, we were unable to confirm any identities. According to the whistle-blower, however, they had been standing in the way of lasting solutions to the procurement problems for a number of years.

“One has to dissect the procurement process bit by bit,” the whistle-blower informed us, in another of the explanatory emails. “Instead of tackling the whole animal, you have to individually assess, analyse and investigate each sub-process to really see what is going on. The work stream attempted doing this and finished between two and four [sub-processes], if I remember correctly. Again, why did this work stop? Middle management.”

By the “work stream,” the whistle-blower meant the task teams that had been assigned to implement the recommendations of 2019; by “middle management,” he or she meant that it was this layer of Eskom’s staff complement that had the most to lose from any solutions.

Put another way, it wasn’t that the procurement problems couldn’t be fixed, it was that there were too many employees with a vested interest in ensuring that the system stayed broken.

In this regard, there was one final paragraph that we received from the Eskom media desk in response to our detailed questions, and on the surface it had to do with documents 32-1033 and 32-1034:

“Eskom would like to confirm that the Eskom procurement and Supply Chain Management procedure remains relevant. It is aligned to relevant legislation and National Treasury Instruction Notes. Eskom however continuously strengthens its system controls by way of enhancements or improvements, based on any gaps identified. To that end, we have engaged external attorneys to review our current procedures.”

So what the media desk was responding to below the surface, it appeared, was our consistent question — asked at various points in our request for comment — about the current status of the holes in the procurement system.

Had “any gaps” — to use their phrase — been identified?

By any account of the evidence, the answer was a resounding “yes”.

And so what exactly were the “enhancements and improvements” that Eskom was referring to? We were not told, simply because the media desk felt it was sufficient to inform Daily Maverick that “external attorneys” had been engaged.

Of course, it was unlikely that these nameless attorneys were going to risk their contract by calling out Eskom middle management and the officials at National Treasury. If the two accountable institutions were passing the buck by referring to each other, as they were obviously doing in their responses to our questions (see the 13-page request for comment from National Treasury below), how was an external private sector firm going to force their hand?

It was, sadly for the citizens of South Africa, the very essence of the Kafkaesque. And the only thing that might have done the job was a visit from law enforcement.

But that was another story; one that had yet to be told. DM