There have long been claims that ANC bigwig Zweli Mkhize collected alleged kickbacks from investment deals involving the state-owned Public Investment Corporation (PIC).

This happened when Mkhize held the powerful position of ANC treasurer-general, or so the rumours went.

Today, Scorpio reveals what may be the first compelling evidence in support of these allegations.

Our months-long investigation links a R5.9-million payment for a property purchased by Mkhize’s trust to a substantial transaction fee earned off the back of a huge funding deal facilitated by the PIC.

The R1.37-billion investment was bankrolled with monies from the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF).

The PIC acts as an investment manager for the UIF.

We can reveal that a company owned by well-known PIC dealmaker Lawrence Mulaudzi in 2018 paid R5.9-million into a transfer attorney’s account for an upmarket townhouse bought by Mkhize’s ZLM Trust.

Mulaudzi’s company, Blackgold Oil and Gas, made the payment only one day after it had pocketed a R47.5-million fee for “advisory” work on the R1.37-billion PIC/UIF deal.

According to Mulaudzi, the payment to the ZLM Trust had been for a “legitimate business transaction”.

He strongly denied that it had been an alleged kickback paid to Mkhize in relation to Mulaudzi’s dealings with the PIC.

Mkhize ignored our efforts to obtain his comment on the matter.

Mulaudzi, a key figure in several controversial PIC funding deals, featured in a series of allegations contained in emails from a PIC whistle-blower.

The emails, circulated under the pseudonym “James Nogu”, partly led to the establishment of Judge Lex Mpati’s Commission of Inquiry into the PIC’s affairs in early 2019.

Businessman Lawrence Mulaudzi testifying at the PIC inquiry. (Photo: Supplied)

Businessman Lawrence Mulaudzi testifying at the PIC inquiry. (Photo: Supplied)

Among an array of claims, “Nogu” alleged that Mulaudzi had clinched huge funding deals from the PIC because of his close ties to PIC board member Sibusisiwe Zulu.

“Nogu” also alleged that Mkhize was Zulu’s “uncle” and that she and Mkhize had shared in some of the spoils from Mulaudzi’s PIC deals.

(Zulu has denied that she is Mkhize’s niece and has won a Press Ombudsman case in this regard. However, it is no secret that she is close to Mkhize, who appointed her as his chief of staff when he was health minister.)

Claims of Mkhize’s alleged involvement in dodgy PIC deals weren’t limited to the “Nogu” emails.

Some allegations even surfaced during court proceedings.

To date, however, Mkhize has not faced any fallout resulting from these allegations.

The Mpati Commission made scathing findings regarding Mulaudzi and Zulu’s involvement in PIC deals, but Mkhize was spared such censure.

Scorpio’s latest revelations should at the very least fuel fresh impetus for law enforcement bodies to revisit this matter.

The R1.37-billion Bounty deal

Mulaudzi’s earliest PIC funding coup came in 2015, when he formed part of a consortium that clinched a R1.8-billion PIC investment to acquire an empowerment stake in fuel giant Total South Africa.

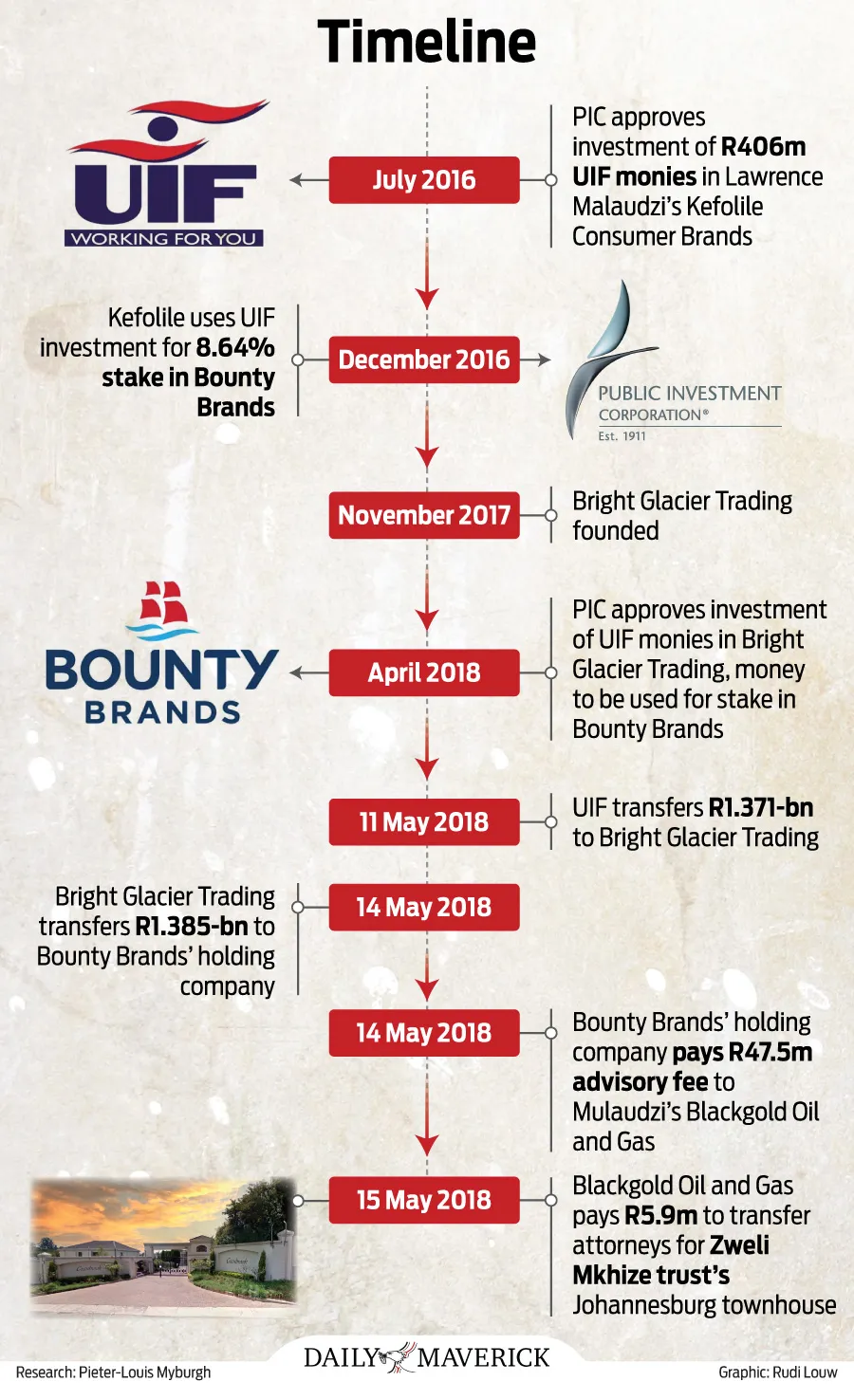

The following year, the PIC green-lighted a deal whereby R406-million in UIF funds were invested in another Mulaudzi entity, Kefolile Consumer Brands.

With this money, Kefolile acquired an 8.64% stake in Bounty Brands.

The latter business owns and distributes an array of well-known consumer brands, mostly in the foodstuff, home care and clothing spaces. Diesel, Vans and Hurley apparel, Häagen-Dazs ice-cream and Cheerios cereal fall within the Bounty stable, with a host of other brands.

In return for the R406-million investment, the UIF secured a 50% stake in Mulaudzi’s Kefolile, which gave the UIF an indirect stake in Bounty Brands.

But Bounty Brands, led by CEO Stefan Rabe and CFO Peter Spinks, needed even more funding.

The task of raising new funds, however, was not Rabe and Spinks’ responsibility.

Instead, Coast2Coast Capital, the private equity firm that founded Bounty Brands, was mandated to perform this function.

Coast2Coast turned to Mulaudzi for assistance, who in 2018 helped broker an investment deal with a company called Bright Glacier Trading.*

Like Mulaudzi’s Kefolile, Bright Glacier’s cash came from public funds.

Again using UIF monies, the PIC invested a massive R1.37-billion in Bright Glacier.

The UIF took a 40% stake in Bright Glacier, which used the R1.37-billion to buy a 36.28% share in Bounty Brands’ holding company.

Through its investment in Bright Glacier, the UIF now owned an indirect stake in Bounty Brands’ holding company, along with its indirect stake in Bounty Brands itself via Kefolile.

The dealmaker

Dr Lynette Moretlo Molefi, Bright Glacier’s managing director, confirmed that Mulaudzi had acted as a dealmaker in the R1.37-billion PIC/UIF investment.

“He brought the deal to me,” explained Molefi.

In essence, Mulaudzi had also brought the deal to Bounty Brands’s majority shareholder, Coast2Coast.

It was for these efforts that Bounty Brands paid Mulaudzi’s Blackgold Oil and Gas the R47.5-million fee.

“The PIC was aware of this fee”, Bounty’s CEO, Rabe, told us.

His partner, Spinks, said Mulaudzi’s company had acted as a “capital raising and deal origination adviser”.

We’ll circle back to this payment in a bit.

It is worth noting the following: the R406-million investment in Mulaudzi’s Kefolile and the R1.37-billion Bright Glacier deal were both processed and approved by the same PIC Fund Investment Panel, or FIP.

This FIP was chaired by none other than Sibusisiwe Zulu, the PIC board member mentioned in the “Nogu” emails.

Some of the emails alleged that Mulaudzi had pocketed a R100-million fee from the 2015 Total deal and that he had shared R40-million with Zulu and Mkhize.

Mkhize’s ‘cut’

We’re yet to uncover any evidence for Mkhize’s alleged benefit from the Total deal.

But something remarkably similar appeared to have occurred in relation to the R1.37-billion Bright Glacier transaction.

We were led to this discovery during our earlier work on the Department of Health’s (DoH) Digital Vibes scandal.

In May 2021, we revealed that Digital Vibes had paid for minor maintenance work at a property in Bryanston, Johannesburg.

The townhouse was owned by Mkhize’s ZLM Trust.

At the time, Mkhize was in charge of the DoH, and Digital Vibes sat with a R150-million communications contract from Mkhize’s department.

We looked at the property’s deeds office records and spotted a red flag:

The ZLM Trust had bought the townhouse for R7.9-million, without a bond.

In other words, Mkhize’s trust had somehow scraped together more than R8-million to cover the purchase price, transfers fees and related costs.

This is a bulky pile of cash by anyone’s standards, even for a top politician and his family.

Zweli Mkhize’s ZLM Trust bought an R8-million townhouse in this complex in Bryanston, Johannesburg. (Photo: Google Street View)

Zweli Mkhize’s ZLM Trust bought an R8-million townhouse in this complex in Bryanston, Johannesburg. (Photo: Google Street View)

Before the property was registered in the trust’s name in May 2018, the transfer attorneys received a series of large payments, our investigation showed.

This consisted of a payment of R771,000 in January 2018; one of roughly R1.6-million in March 2018; and, finally, the R5.9-million transfer in May 2018.

It is not clear where the money for the first two payments originated from, but we managed to establish that the R5.9-million payment had come from Mulaudzi’s Blackgold Oil and Gas.

But there is much more to it than just that.

Our investigation revealed that the payment was almost certainly funded from the R47.5-million fee that Mulaudzi’s company had pocketed from Bounty Brands.

And because the R47.5-million fee had stemmed from Bright Glacier’s UIF-funded investment in Bounty Brands, it stands to reason that the property acquired by Mkhize’s ZLM Trust had largely been bankrolled with UIF monies.

Consider the following sequence of transactions and events:

- On 11 May 2018, the UIF transferred the R1.371-billion to Bright Glacier Trading, after the PIC had approved the investment.

- Three days later, on 14 May, Bright Glacier transferred all of the UIF funds, along with an additional R14-million, to Bounty Brands’ holding company, an entity simply registered as K2015388659.

In other words, Bright Glacier had paid R1.385-billion for its 36.28% stake in Bounty Brands’ holding company.

- On that same day (14 May 2018), Bounty Brands’ holding company transferred the R47.5-million fee to Mulaudzi’s Blackgold Oil and Gas.

- The following day, Blackgold Oil and Gas transferred R5.9-million to the transfer attorneys for the property purchased by Mkhize’s ZLM Trust.

- The property was finally registered in the trust’s name on 22 May 2018, according to deeds records.

- The ZLM Trust sold the property in February 2021 for just over R6-million, considerably less than the R7.9-million purchase price.

It is our understanding that the townhouse had fallen into a somewhat neglected state, hence the reduced price.

Mulaudzi’s stance

We sent detailed queries to Mkhize regarding his trust’s property and the large payment from Mulaudzi’s company.

The former health minister appeared to have read our messages, but he did not respond.

Zulu was nearly as reticent.

We wanted to know whether she had been aware of the payment that Mulaudzi had made for the ZLM Trust’s property deal.

During a brief phone call, she said she had just had a baby and would not be able to respond to our queries.

“Please send it to Dr Mkhize, I have no mandate to deal with it,” said Zulu.

Mulaudzi, on the other hand, was willing to discuss the matter.

He strongly denied that the R5.9-million transfer was in any way related to the PIC/UIF transaction.

The payment had been for a “legitimate business transaction” with the ZLM Trust, said Mulaudzi.

“Dr Mkhize has not participated or contributed to any of my business transactions (or received a cut as you put it), including those concluded with the PIC,” he stated.

Zweli Mkhize in 2017, when he was the ANC’s treasurer-general. (Photo: Gallo Images/ City Press / Leon Sadiki)

Zweli Mkhize in 2017, when he was the ANC’s treasurer-general. (Photo: Gallo Images/ City Press / Leon Sadiki)

We pressed him for specifics on the business deal between his company and the ZLM Trust, but he didn’t share such details.

Mulaudzi also claimed that he had not been aware of Mkhize’s involvement with the ZLM Trust.

“My team and legal representatives have verified all the documents including legal agreements and FICA documents that were there when we concluded business with [the] ZLM Trust.”

“There is no document signed by Dr Zweli Mkhize or any FICA documents reflecting his involvement or ownership of the trust. We are therefore not sure where your statement ‘Dr Zweli Mkhize’s ZLM Trust’ emanates from,” stated Mulaudzi.

For all we know, Mkhize’s signature may very well have been absent from the documents Mulaudzi and his team had processed for the “legitimate business transaction” with the ZLM Trust.

But, as we pointed out to him, there were several clear markers tying the trust to Mkhize and his family:

- “ZLM” are the former health minister’s initials;

- Mkhize’s surname and cellphone number appeared on the invoices for the maintenance work at the trust’s property that Digital Vibes had paid for in 2020;

- Mkhize at times lived at the townhouse after the trust had bought it;

- The former minister’s wife, Dr May Mkhize, is listed as a trustee; and, finally

- Dr May Mkhize herself has admitted in writing that the townhouse was a “family property”.

Mulaudzi chose not to comment on these specifics.

He claimed that he and his team “are also not aware of the property acquisition you mention”, which was rather curious.

After all, the R5.9-million payment from his company went directly to a transfer attorney’s account for no other purpose than the property deal.

We sought further clarity on what he had meant by this, but to no avail.

“Your previous response to me showed that you have made up your mind because you have unfortunately wrongly concluded and are ‘sure’ that I paid a ‘kickback’,” he said.

“I am therefore not sure if any further engagement with you would be of any value.”

We also wondered whether Bright Glacier Trading had known about the fee Bounty Brands had paid to Mulaudzi’s company.

More importantly, we wanted to know if they’d had any knowledge of the large payment Mulaudzi subsequently made to the benefit of Mkhize’s trust.

Rachel Mphephu, one of Dr Molefi’s fellow directors in Bright Glacier Trading, said she and her partners “were not aware of the fees and transfers” in question, “nor did [they] play any role in determining or facilitating them”.

Bounty Brands’ principals, meanwhile, said they had no knowledge of how Mulaudzi had utilised the R47.5-million fee they had paid to Blackgold Oil and Gas.

“None of the directors of Bounty Brands have any knowledge of alleged corrupt activity on the part of Mr Mulaudzi, other than the information released via [the] press or the PIC Commission conducted in late 2018”, stated Rabe.

Because of the negative press and the Mpati Commission, Bounty Brands had no further association with Mulaudzi or with Blackgold Oil and Gas, added Rabe.

According to the PIC, the entity “did not deal with Mr Lawrence Mulaudzi and/or Blackgold Oil and Gas in the Bright Glacier transaction”. DM

* This article has been amended after its initial publication to more accurately reflect the dynamics within the broader Bounty Brands group. Bounty Brands’ principals, Rabe and Spinks, were not involved in the negotiations with Mulaudzi or with any other parties in regard to the UIF/PIC funding deal. In line with its responsibilities as the private equity business that founded Bounty Brands, Coast2Coast Capital handled these tasks.

Zweli Mkhize in 2017, when he was the ANC’s treasurer-general. (Photo: Gallo Images/ City Press / Leon Sadiki)

Zweli Mkhize in 2017, when he was the ANC’s treasurer-general. (Photo: Gallo Images/ City Press / Leon Sadiki)