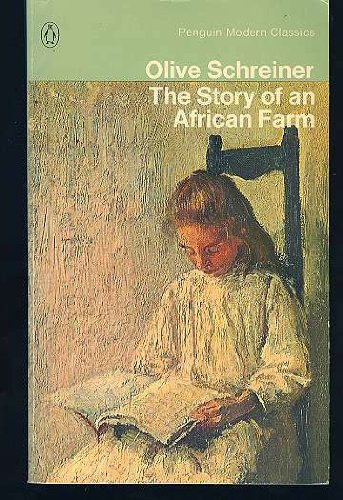

I was browsing in a London second-hand bookshop – looking for the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom or Che Guevara’s Guerrilla Warfare or anything else banned in South Africa – when I absentmindedly picked up the Penguin Modern Classics edition of Olive Schreiner’s The Story of an African Farm. Perhaps it was the cover that caught my eye. The English Honours course at Rhodes offered various modules, including South Africans and Americans. It was a no-brainer. I mean, who in their right mind would waste their time reading a South African novel when you could be reading Fitzgerald, Hemingway and Faulkner?

Of course, there were a few exceptions. I’d been blown away by Athol Fugard’s plays and I loved Herman Charles Bosman’s short stories but – with youthful arrogance – I dismissed all others sight-unseen as parochial and second-rate. But on that wintry day, it may have been Frans Oerder’s painting Girl Reading on the cover that triggered my impulse purchase. Back in my digs, having already prejudged it as mediocre and provincial, I opened the novel and read the first paragraph.

The Story of an African Farm with Frans Oerder’s painting Girl Reading on the cover.

The Story of an African Farm with Frans Oerder’s painting Girl Reading on the cover.

“The full African moon poured down its light from the blue sky into the wide, lonely plain. The dry, sandy earth, with its coating of stunted ‘karroo’ bushes a few inches high, the low hills that skirted the plain, the milk-bushes with their long finger-like leaves, all were touched by a weird and almost oppressive beauty as they lay in the white light.”

Schreiner’s passionate and magical novel was a revelation. More than a quarter of a century later – after my mum and dad had died – I discovered that for several years after I’d left the country Dad had kept my letters home. In one posted shortly after I’d read Schreiner’s novel, I’d written saying I’d give almost anything just to spend 24 hours in the Karoo.

The N1 in 1990 that seemed empty nothingness when I was a child. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

The N1 in 1990 that seemed empty nothingness when I was a child. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

But why would a novel that takes place in the Karoo make me homesick? I was born in Durban. Indigenous coastal bush, sugarcane plantations and the green hills of Natal’s Midlands were in my DNA. Not the arid Karoo. All the Karoo had meant to me was staring through the back window of Dad’s Peugeot 203 at the 400 miles of empty nothingness between Colesberg and the Hex River Pass on childhood trips to Cape Town.

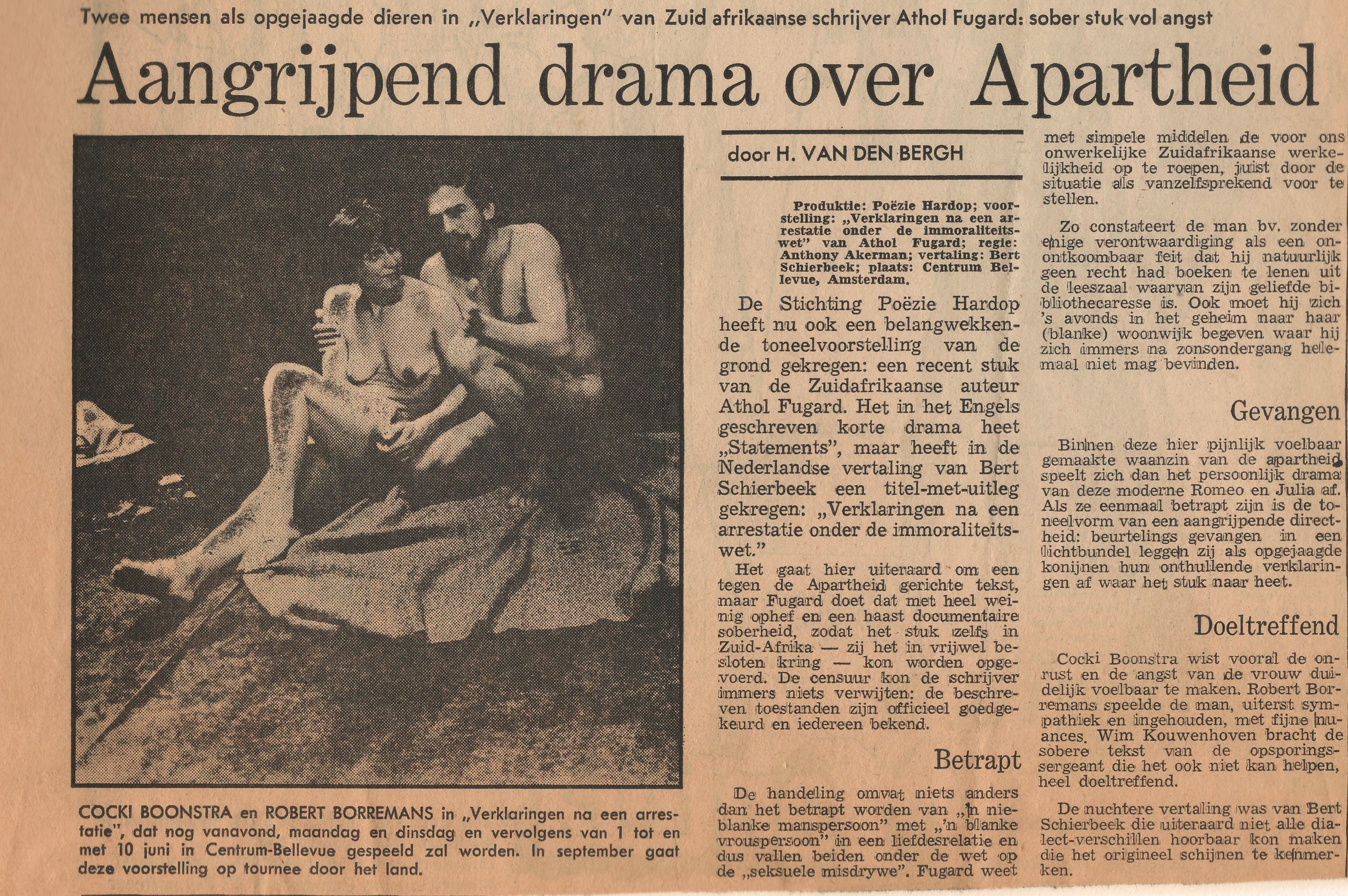

But Schreiner had planted a seed, and it was Fugard who watered it and taught me to love the stark beauty of his world. He’s written about having a sense of himself as a “regional” writer, and many of his plays take place in and around Port Elizabeth. The first of his plays situated in the Karoo, in the small town of Noupoort, is Statements after an Arrest under the Immorality Act – a play I directed in Amsterdam in 1976.

Review of Statements 1976. (Image: Supplied)

Review of Statements 1976. (Image: Supplied)

Errol Philander, a schoolteacher with an all-consuming interest in evolution, is prohibited from using the town’s whites-only library, but Frieda Joubert, the sympathetic librarian, orders the books he needs and hands them to him through the back door. They fall in love and that’s their undoing. But before their arrest, Errol excitedly tells Frieda about the last book she’d ordered for him.

“This little piece of earth, the few miserable square feet of this room … this stupid little town, this desert … was a sea, millions and millions of years ago. Dinosaurs wallowed here! Truly. That last book mentions us: ‘The richest deposits … Permian and Triassic periods … are to be found in the Graaff-Reinet district of the Cape Province of South Africa.’ Us. Our world.”

Noupoort is only 40km from Middelburg, the town where Fugard was born – and where, somewhat serendipitously, Olive Schreiner married Samuel Cronwright in 1894.

In 1981, Athol came to Amsterdam for the opening of my Dutch-language production of A Lesson from Aloes. Although he lived in Sardinia Bay, in a home tellingly named The Ashram, in the mid-1970s he’d paid – if memory serves me well – R100 for a house in the Karoo village of Nieu Bethesda.

Nieu Bethesda in 1990, where Athol Fugard wrote many of his plays. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

Nieu Bethesda in 1990, where Athol Fugard wrote many of his plays. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

Nieu Bethesda is 100km from where he was born, off the beaten track and – something we’re all becoming increasingly accustomed to – at the time, it was also off the national electricity grid. It was an escape, somewhere he could write his plays without the distractions that came with international success.

Although he spent increasingly longer periods directing his plays in the United States, Athol always returned home to write. He told me he had a homing instinct and couldn’t write anywhere else.

In 1960, in London, he’d made notes for a play about two brothers, classified under South Africa’s race laws as Coloured – although one had the pigmentation of a black African and the other could “pass for white”. He still didn’t have a title, but at the end of the year he returned to Port Elizabeth and that’s where he wrote what came to be known as The Blood Knot. It was the first play that bore many of the hallmarks of his later work and the only Fugard play I’ve ever directed in English with South African actors.

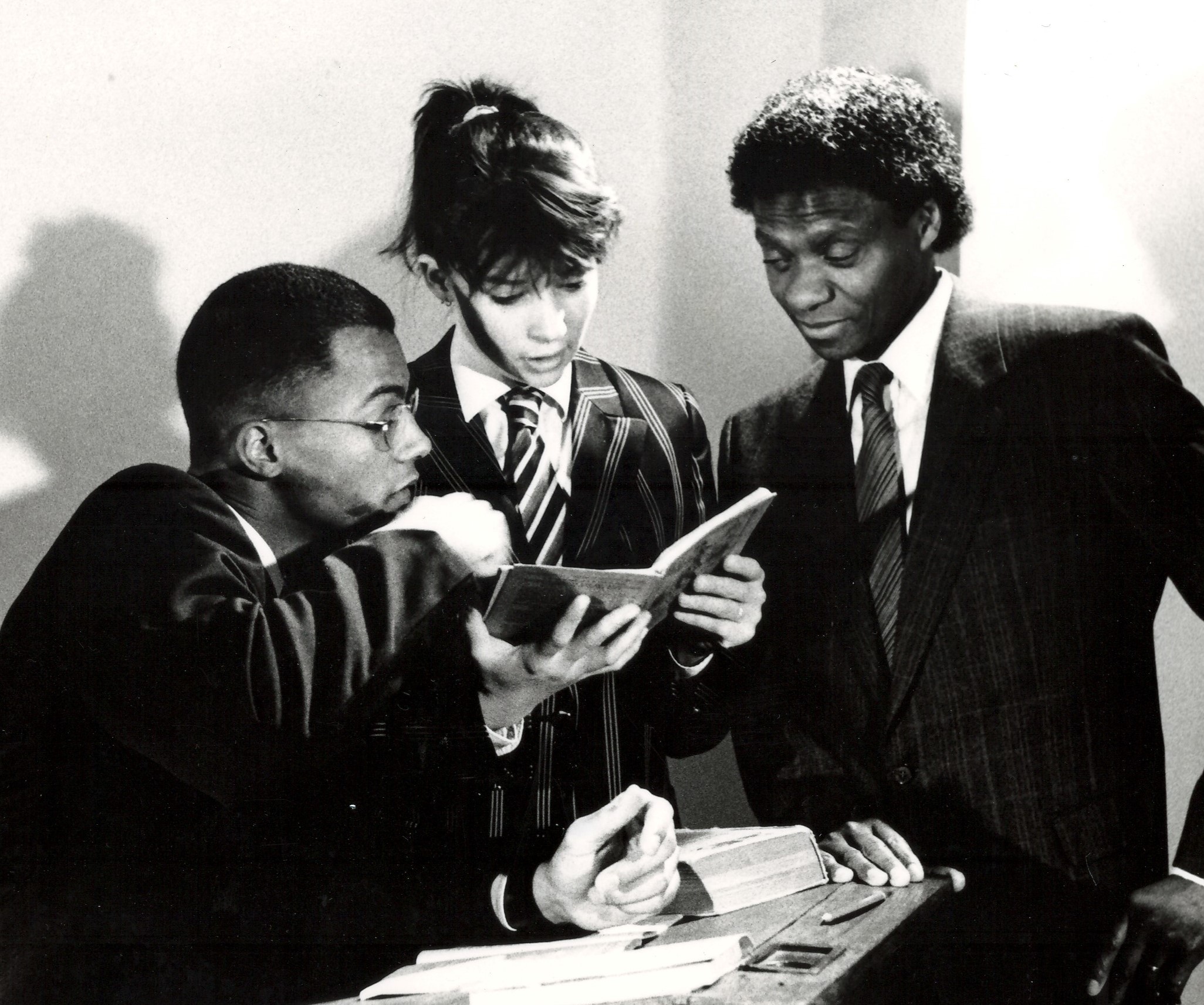

South African actors Ian Bruce and Joseph Mosikili in 'The Blood Knot', Amsterdam 1984. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

South African actors Ian Bruce and Joseph Mosikili in 'The Blood Knot', Amsterdam 1984. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

Athol’s words came back to haunt me when I sat down to write my first play. Schreiner wrote The Story of an African Farm on various Karoo farms – finishing it while staying with the Cawoods at Gannahoek – and 100 years later Athol was writing his plays in Nieu Bethesda. I was in Amsterdam. Would this make Somewhere on the Border less authentically South African?

Then I comforted myself with the thought that some of the most achingly beautiful Afrikaans poetry had been written in Paris by Breyten Breytenbach and that – in September 1946 while staying at the Hotel Bristol in Trondheim, Norway – Alan Paton sat down and, before going out to meet his hosts for dinner, wrote down the opening paragraph of Cry, the Beloved Country. Set in a part of the world I knew well, it’s an opening paragraph that rivals Schreiner’s in evocative beauty:

“There is a lovely road that runs from Ixopo into the hills. These hills are grass-covered and rolling, and they are lovely beyond any singing of it. The road climbs seven miles into them, to Carisbrooke, and from there, if there is no mist, you look down on one of the fairest valleys in Africa.”

When Athol arrived in Amsterdam in 1981, he’d just finished writing “Master Harold” … And the Boys in Nieu Bethesda. The next play he wrote there was inspired by the life of a local artist who’d been misunderstood and maligned by the inhabitants of that village.

It must have been shortly before Athol picked up his fountain pen to keep his appointment with The Road to Mecca that Breytenbach surprised me with a perplexing piece of information. He was in Amsterdam for the opening of Eksel, a production I’d staged with three Dutch actors using his as-yet-unpublished prison poems.

Breyten said: “Did you know Athol’s joined the AA? He’s getting up and speaking at meetings.” No, I didn’t know. I knew Athol’s sympathies were unquestionably Anti-Apartheid but I didn’t think he’d actually become an activist, join an organisation and address political meetings. “No,” said Breyten, correcting my misapprehension. “Alcoholics Anonymous.”

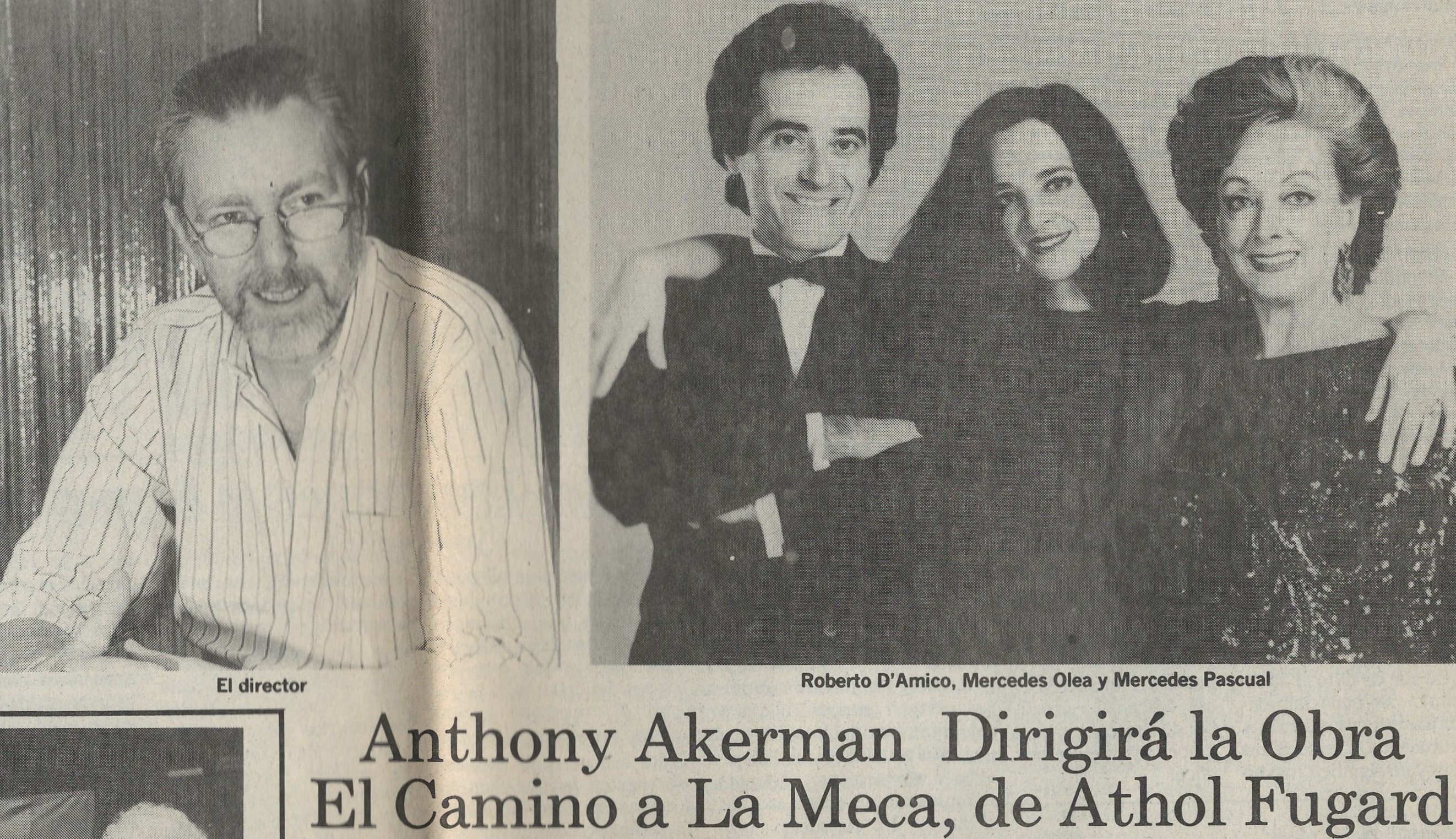

When Athol finished writing The Road to Mecca, he told the press it was the first play he’d written without alcohol. Theatregoers held their breath wondering if it would live up to his previous work. I’d heard stories of literary agents who’d rather their clients died of cirrhosis of the liver than have them sober and run the risk they’d produce work that may have lost its alcohol-induced magic. When I saw the production at the National Theatre in London, it was vintage Fugard – a slow-burning exposition and a cathartic climax.

El Camino a la Meca 1995. (Archive image: Supplied)

El Camino a la Meca 1995. (Archive image: Supplied)

Two years after he bought his house in Nieu Bethesda, the real Helen Martins – who’d transformed the home she’d inherited from her parents into the Owl House – committed suicide by drinking caustic soda. There’s some speculation she did so because she felt her creative muse had deserted her and she had nothing more to live for. Athol’s Miss Helen confronts her demons and – like many of his female characters – she survives her dramatic ordeal.

On a coded level, the play tells a parallel story of Athol’s triumph over the threat alcoholism posed to his own creativity. When the play opened, he told the Star that Miss Helen was “actually a self-portrait”.

I wrote to him after seeing the production and received a reply from The Ashram in April 1985, shortly before he left to direct the play on Broadway. He was still waiting to hear whether American Equity would allow Yvonne Bryceland to play Miss Helen. He said he was in good health, but not in good spirits. “The situation in the country and here in the EP in particular is the worst I have ever known,” he wrote. “I think I now totally despair of the future.”

In July 1989, I read about My Children! My Africa! in the Weekly Mail. It was the first Fugard play to have its world premiere in South Africa in over a decade. Athol had tackled one of the issues that had caused him to feel so pessimistic about the country’s future: the crisis in education.

School boycotts and slogans such as “first liberation, then education” would bequeath a lost generation to the country, something we’ve never fully recovered from. I received the script from his agent in October, liked the play, approached Wim Visser – the producer who’d introduced Pieter-Dirk Uys to the Netherlands – and we scheduled a production for early 1991.

But a year before we went into rehearsal, FW de Klerk delivered his watershed speech, Nelson Mandela walked out of Victor Verster and the South African Embassy in The Hague no longer had a reason to refuse me a visa.

I was 40 when I returned home after an absence of 17 years – and met my birth mother for the first time. But that’s another story – the story of my adoption which I’ve told in a yet-to-be-published memoir called Lucky Bastard.

In 1990, I visited South Africa twice. During my second visit – after directing Somewhere on the Border in Durban – I flew down to Cape Town to spend more time with my birth mother Vera. I’d suggested we go on a road trip through the Karoo. Not only would that give us quality time together, but I’d also get to visit a part of the world I’d been longing for since that English winter when I’d read The Story of an African Farm.

As we drove through Paarl, Vera told me I’d lived there “in utero” for five months. We then drove over the Du Toitskloof Pass, which I now knew was named after my ancestor François du Toit. We arrived in Matjiesfontein in time for a pub lunch at the Lord Milner Hotel. Unfortunately, we couldn’t visit Schreiner’s cottage as it is now part of the hotel and the room was occupied.

Olive Schreiner's cottage Matjiesfontein. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

Olive Schreiner's cottage Matjiesfontein. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

Finding a Karoo town where Olive Schreiner never lived might well prove as difficult as finding a restaurant in Spain where Ernest Hemingway never had lunch.

The Karoo landscape I’d found desolate and boring as a child I now found hauntingly beautiful. I stopped the car. Vera asked if something was wrong. I just wanted to get out and be in the middle of it. It had recently rained, and splashes of veld flowers were growing along the side of the road.

Vera had told me her father – my grandfather – had been born in Cradock in 1867, the year the 12-year-old Olive went to live there and received her first years of formal education. So perhaps the Karoo was in my DNA after all. When I got back in the car a few minutes later not a single vehicle had passed us in either direction.

At Beaufort West we took the R61. The landscape flattened out – windmills pumping water, Merino sheep cropping Schreiner’s “stunted ‘karroo’ bushes”, springbok twitching their tails. We approached Graaff-Reinet from Aberdeen and checked in at the Drostdy Hotel – originally built as a magistrate’s court in an attempt to impose law and order on an unruly and rebellious frontier population.

'Mijn kinderen! Mijn Afrika!' By Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1991. South African actor Joseph Mosikili played Mr M in Dutch. (Photo© Tet Lagemaat)

'Mijn kinderen! Mijn Afrika!' By Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1991. South African actor Joseph Mosikili played Mr M in Dutch. (Photo© Tet Lagemaat)

Graaff-Reinet is the setting of My Children! My Africa! In the play, before going out to meet his death, the schoolteacher Mr M describes an epiphany he’d had as a 10-year-old child standing at the top of the Wapadsberg Pass. I wanted to drive up there, stand where he’d stood and see what he described.

“… there it was, stretching away from the foot of the mountain, the great pan of the Karoo … stretching away for ever, it seemed, into the purple haze and heat of the horizon. Something grabbed my heart at that moment, my soul, and squeezed it until there were tears in my eyes. I had never seen anything so big, so beautiful in all my life.”

Anthony Akerman at the top of the Wapadsbergpas 1990. (Image: Supplied)

Anthony Akerman at the top of the Wapadsbergpas 1990. (Image: Supplied)

I’d told Vera about the Owl House and how it had featured in The Road to Mecca – a play I would go on to direct in Mexico City in 1995. Could Athol have foreseen his play would popularise Nieu Bethesda as a tourist destination – and perhaps even make him a tourist attraction? As we drove along the dirt road, I told Vera how Athol had bought a house in the village for a song and always went there to write. I’d received a note from him on 8 April saying he was going to the US, but by now he could have been back home working on a new play.

When we pulled up outside the Dutch Reformed Church, I saw a car with a CB registration and said it must be him. As I got out of the car, I saw the front door of a house opening and Athol walking towards me. He didn’t seem to recognise me, so I called out his name.

“Wrong Fugard,” he answered. He told me he was Athol’s older brother, Royal.

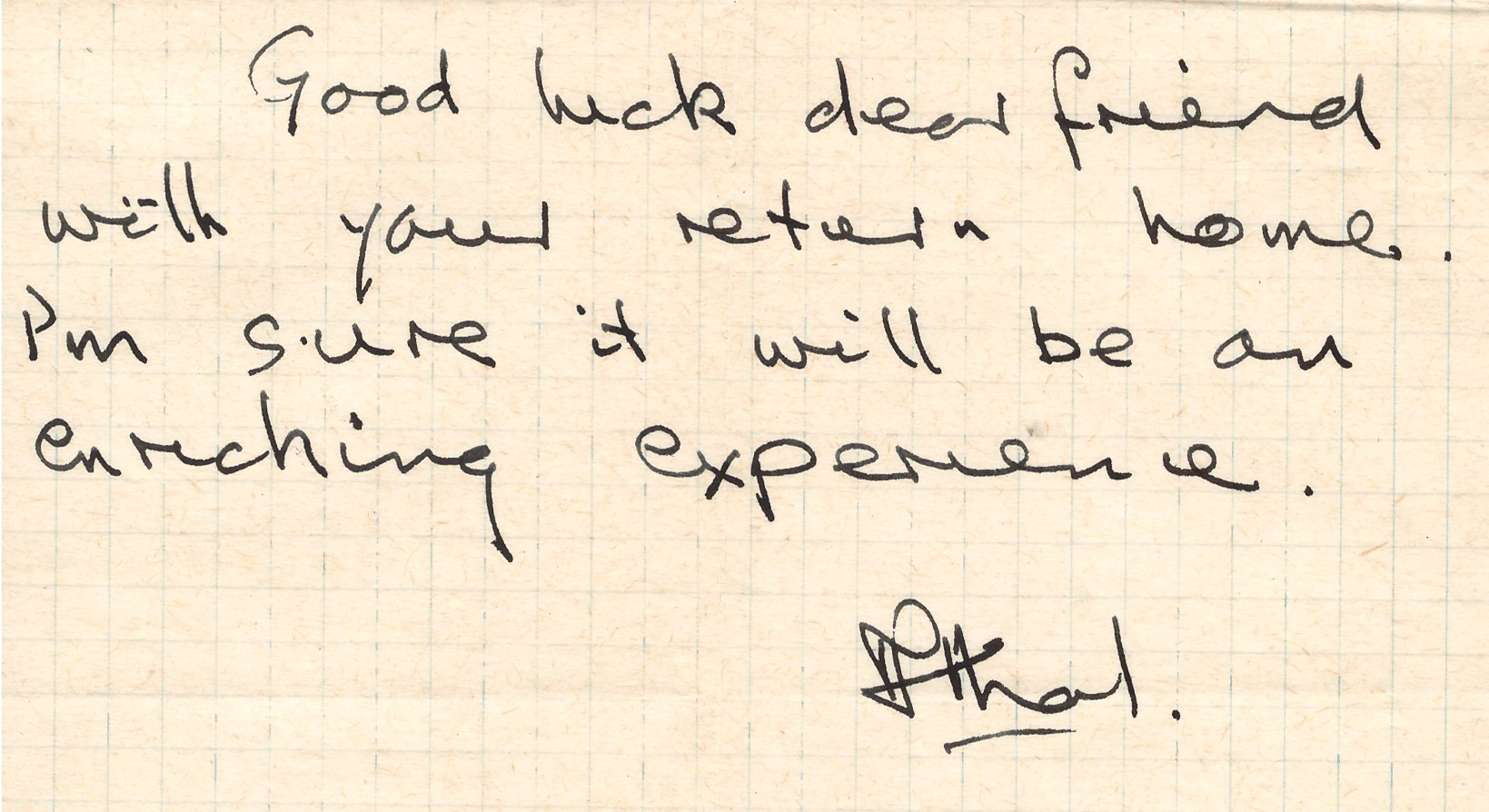

Letter from Athol Fugard 8 April 1990. (Image: Supplied)

Letter from Athol Fugard 8 April 1990. (Image: Supplied)

My mother Vera Milner (née Farnham), Louise & Royal Fugard, Nieu Bethesda 1990. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

My mother Vera Milner (née Farnham), Louise & Royal Fugard, Nieu Bethesda 1990. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

I told Roy – that’s what everyone called him – how I knew Athol. We were joined by his Dutch wife Louise, and they invited us into their home for tea. They’d also bought in Nieu Bethesda. If we’d been here a few weeks earlier, Roy told me, we’d have seen Athol. He’d been there to buy a house for his daughter Lisa. He probably paid a lot more than R100 for it. Roy said Athol was already back in America.

I surprised Louise by speaking Dutch to her and then we explained how my mother and I had met for the first time that year. Roy and Louise said they knew someone else who’d been adopted. Everyone does. They said you could see Vera and I were mother and son. You could also see Royal and Athol were brothers, but in other respects, they were very different. Athol had won a scholarship to UCT to study Philosophy, while Roy had had a poor academic record. Athol worked in the theatre, while Roy worked for the Parks Board.

Before we left to visit the Owl House, Roy gave me a piece of kudu biltong. I didn’t ask, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he’d shot the kudu himself. He shook my hand warmly and then I remembered reading a quote in which Athol had said The Blood Knot “is basically myself and my brother”. So if Athol was Morris, Roy was Zach. I wondered if he’d ever seen the play and, if he had, whether he’d recognised himself and what he thought about the way he’d been portrayed. DM

My mother Vera Milner (née Farnham), Lucille & Royal Fugard, Nieu Bethesda 1990. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)

My mother Vera Milner (née Farnham), Lucille & Royal Fugard, Nieu Bethesda 1990. (Photo© Anthony Akerman)