Growing up as Kgositsile, meaning “king”, Tshiamo Modisane always knew that she was a girl despite her assigned birth gender.

As the talented child of a pastor from KwaThema and Daveyton townships near Johannesburg, Modisane was expected to conform to conservative black culture’s expectations for a male, and endured censure and even abuse from family, friends, peers and strangers into adulthood.

Modisane began making courageous choices at the age of five, and a journey of both self-doubt and self-belief that culminated in gender-affirmation surgery in her thirties.

With sass, faith and baked-in confidence from her family ties to the entertainment world, she successfully transitioned from male to female while navigating a career as an actress, celebrity stylist and Lux’s first gender-non-conforming brand ambassador.

Her poignant memoir examines past hurts and present truths, and opens up a sorely needed discussion about unconditional acceptance. Read an excerpt from the book below.

***

I was once asked what my favourite part of the day was. My response was simply, “Nighttime, because I get to sleep!” But what I actually meant was, “Nighttime, because it allows me the opportunity to escape my sad reality.” It was the only time I could mentally transport myself to a place where I could relive the day in the gender I resonated with. This is something I still do on days when I feel “less than”. To cope with my anxiety, I developed an invisible alter ego whom I affectionately named Tshiamo.

Tshiamo was everything I believed myself to be, but could not be, because of society and other constricting factors. She lived each minute of each day with me but would react to things differently. For Tshiamo, being ladylike and graceful was the closest thing to godliness, a trait she had picked up from her dearly departed Aunt Dorcas, better known as “Amani” to her nephews and nieces. A dedicated social worker, Aunt Dorcas epitomised what it meant to be a single, independent black woman.

Tshiamo and I were inseparable; we lived in parallel worlds with similar experiences. I can’t count the times that I experienced something and felt so removed from the moment because it made more sense for Tshiamo to live in it instead of Kgosi. At random times of the day, you would catch me deep in conversation with myself, unaware of the world around me. However, I soon learnt that not everyone took kindly to me speaking to myself.

My father, a staunch religious believer who later became a pastor, was the first to object, saying that by speaking to myself, I was entertaining demons. You see, I grew up in a strict Christian family — so strict that I was once instructed to take down the montage of celebrity posters on my bedroom wall because my parents felt this was idol worship. So strict that I wasn’t allowed to watch or play Pokémon or collect the merchandise. So strict that the first sleepover I had, outside of the ones with our pastor’s kid, was at varsity.

So strict that I once got a serious whipping for eating the skin off my sister’s KFC, even though she would have thrown it away anyway. So strict that even when I visited home at age twenty-five, an employed and fully fledged adult, I’d have to be in bed by 9pm — and if I dared stay up on my phone chatting on Mxit, I’d never hear the end of it! So strict that, to this day, my father refuses to acknowledge me as his daughter, which is among the reasons we do not have a relationship. In fact, the only time he acknowledges me is when he’s being condescending or demeaning.

Through all this, Tshiamo was my only glimmer of hope, the ever-shining lamp that lit the path to our perfect future. In fact, some time during our childhood, Tshiamo and I made a pact that we would do our absolute best in school so we could further our studies in the US. At the time, we thought America was our only chance to finally live our truth, our only hope at transitioning without interference from narrow-minded people — a dream that would have materialised had it not been for the fact that the only people who believed in me were my grandmother, who gave me words of affirmation, and the teacher who nominated me, Ms Rauch, a great encouragement and voice of reason throughout my years in high school. Those two became my greatest sources of support.

Physical or verbal abuse

Now that you know just how tight a ship I grew up in, you will understand that there was no way on God’s beautiful planet that I could’ve fully expressed myself without ending up suffering some form of physical or verbal abuse. This, however, fuelled my creative side, and anyone who knows me will vouch for the fact that I live for pushing boundaries. So much so that I found ways of being creative, which allowed me to express myself without fear or compromise.

On any ordinary day when I was around four and five, I would be the kid playing cars with the boys, proudly rocking a scarf around my head, a handbag tucked under my arm. And absolutely no one could shame me. Now that I’m older, I couldn’t be prouder of myself for having put my needs before those of society from an early age. While some would say I was just a confused toddler, I believe that I knew exactly who I was. The world around me just wasn’t ready to embrace me — and not much has changed almost three decades later.

In a lot of respects, many South Africans who grew up in the early nineties can relate to my childhood. With the new song of freedom playing in the country and the positive outlook on life gleaned from our parents and their parents, we somehow inherited an underlying guilt as well as an appreciation for the opportunities we now had. And this guilt and appreciation doubled in measure for a “queer” child: society silently instilled the fear of God in you, in order to make it known that you were not to be seen or heard until you changed your ways… as if you had any say in the matter.

My childhood was firmly defined by the borders of gender and sexuality. Biologically, I didn’t fit into the gender assigned to me at birth, and I was in no way homosexual. Throughout my childhood, but mostly during my pre-teen years, adults and peers alike tried to dupe me into confessing that I was gay, yet this label never resonated with me.

I always explain it thus: that I am a heterosexual woman having a transgender experience. It’s important to understand that being transgendered doesn’t always entail a shared understanding and experience for all who live it. I identify first as a female/she/her/woman/girl before I’m “trans”. I’ve always had difficulty subscribing to the pretext that I’m trans before I’m a woman. Quite frankly, I’ve never understood why cisgender men and women feel the need to impose their ideas of an ideal world on everyone else, leaving us to fit into the category of “other”.

After I turned nine, my mother and her sister, my aunt, thought it best to take me, along with my two cousins, for circumcision. As they explained the procedure to me, all I registered was that there would be a chopping off of some sort down below. I remember praying to and pleading with God to ensure that the surgeon would accidentally cut more than required, thus forcing him to perform a reassignment and correct my penis into a vagina.

Heavily sedated

Needless to say, God answered my prayer, but alas, not in the way I expected. While I was heavily sedated, the doctors discovered that I had an inverted corpus, also known as hypospadias, meaning that the part of my penis known as the head was not in front but inverted. And what was meant to be a one-hour procedure ended up taking longer, causing me to spend a week and a half in hospital. I recall waking up mid-surgery, hoping that the doctors had removed the one thing I believed was misplaced on my body. But before I could utter a word, I was put back to sleep, eventually waking up to the sad realisation that my wishes had not, in fact, been granted. Instead of a flatter genital area, a catheter was connected to my bladder.

Anyone who’s ever had the pleasure of holding a conversation with a toddler will know that these little people are generous with their blatantly honest opinions. Whether good or bad, a toddler will give it to you. It’s always made me wonder, however, why adults tend to censor toddlers, even when they know that they are being brutally honest. I often wonder what my life would have been like had my parents, family and friends heard me when I told them that something was amiss with how I looked. Children always know who they are, and all they ask for is to be accepted just the way that they are. Instead, they grow up in a world where adults claim to know them best.

When it became clear to me that a female’s anatomy was flat around the crotch area, I started tucking at the age of eight. Tucking is a technique where boys or men hide the bulge of the penis and testicles so that they’re not easily visible through clothing. Though my efforts to tuck were not always successful, doing so gave me the comfort that my insecurities weren’t on display for all to see. And even though I was yet to experience puberty, the thought of my crotch area growing, coupled with involuntary erections, gave me serious anxiety — so much so that I found it extremely uncomfortable to be part of any sex-driven conversation; I still feel that way to this day. DM

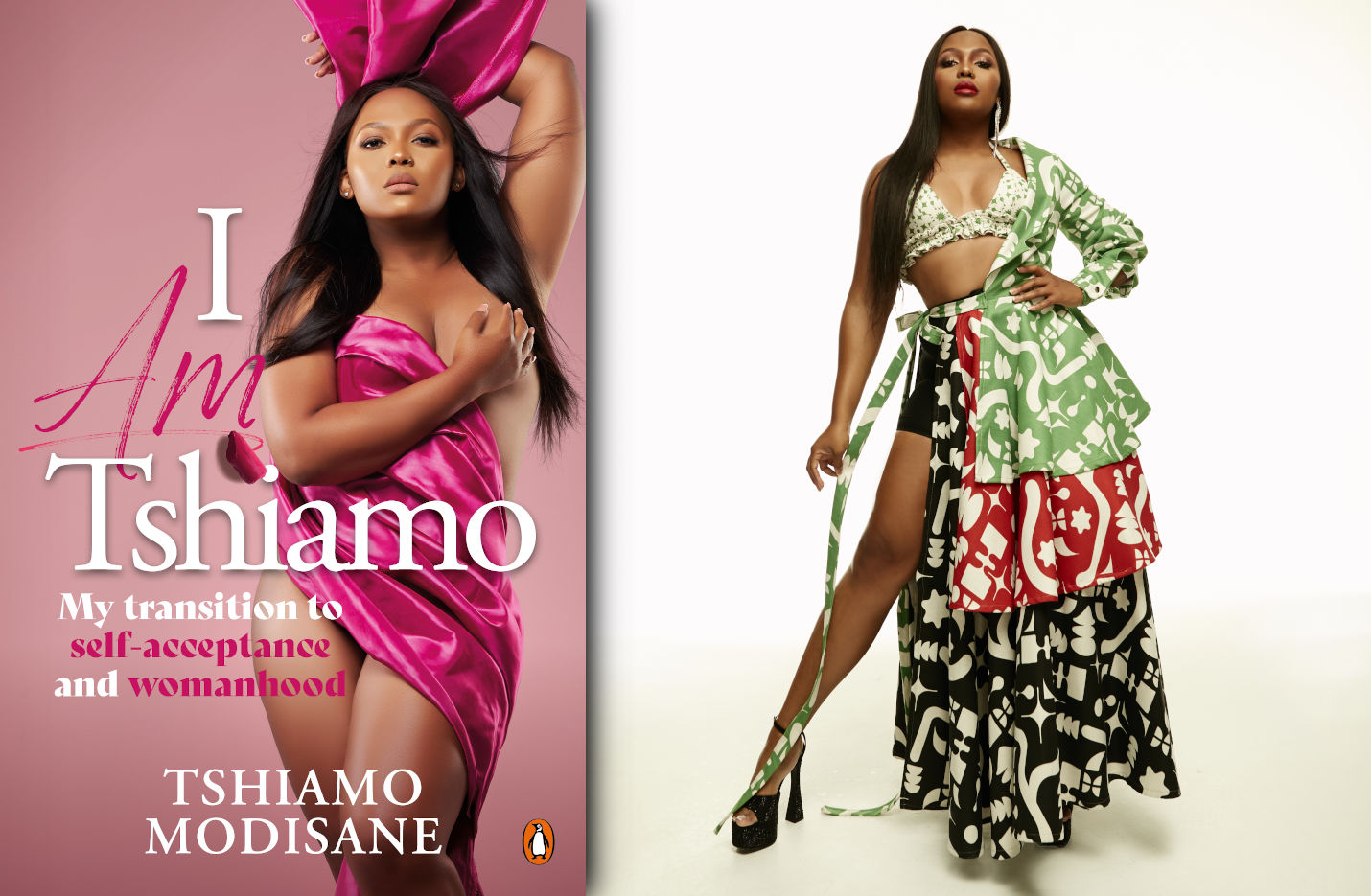

I Am Tshiamo by Tshiamo Modisane is published by Penguin Random House SA (R270). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily — including excerpts!