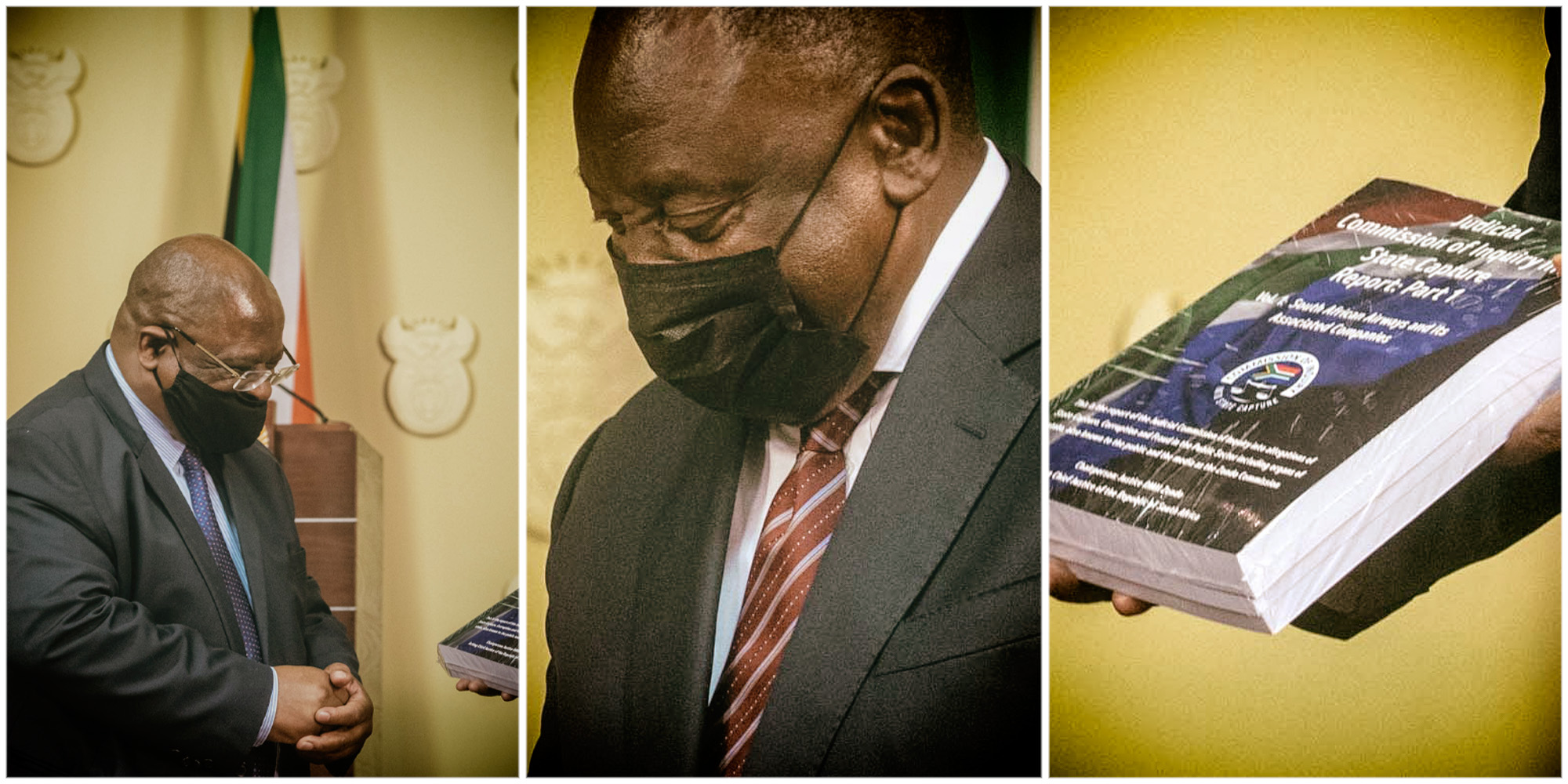

Part One of Deputy Chief Justice Raymond Zondo’s State Capture report, officially handed to President Cyril Ramaphosa on 4 January, proposes far-reaching measures to curb state lawlessness, corruption and malfeasance.

Former Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke and Constitutional Court Judge Edwin Cameron were also vindicated by the commission for their dissenting view in the controversial 2011 Glenister v President of SA judgment.

“State Capture has shown that South Africa needs to heed the view given by the minority in that judgment,” said Zondo.

The majority decision at the time was that there was no constitutional obligation for the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation, or the Hawks, not to be placed within the SA Police Service.

Zondo quoted Moseneke and Cameron’s 2011 view: “There can be no gainsaying that corruption threatens to fell at the knees virtually everything we hold dear and precious in our hard-won constitutional order.

“When corruption and organised crime flourish, sustainable development and economic growth are stunted. And in turn, the stability and security of society is put at risk.”

The Hawks’ predecessor, the Directorate of Special Operations (the Scorpions) reported directly to the National Prosecuting Authority and at the time had been investigating the then deputy president, Jacob Zuma.

In 2007, at its elective conference at Polokwane, the ANC took a decision to shut down the elite unit.

In 2009 Zuma was elected to the highest office in the country.

In 2022 Zondo said that “20 years of frustration, which includes a decade of State Capture, pitilessly exposed the flaws and weaknesses in the public procurement system, flaws and weaknesses which have been exploited by criminals to inflict lasting damage on the South African economy. The promise of service delivery so fundamental to the betterment of our society has not materialised.”

In recommending the establishment of an independent anti-corruption agency, Zondo said that South Africa required such a body “free from political oversight and able to combat corruption with fresh and concentrated energy”.

Public trust would not otherwise be re-established, he warned, adding that “the ultimate responsibility for leading the fight against corruption in public procurement cannot again be left to a government department or be subject to ministerial control”.

Zondo said it was the “view of the commission” that the starting point for any reform “must include the establishment of a single, multifunctional, properly resourced and independent anti-corruption authority with a mandate to confront the abuses inherent in the current system. That authority could be called the Anti-Corruption Authority or Agency of South Africa (Acasa).”

A national charter against corruption, said Zondo, should not only be signed by the president and Cabinet, but all premiers, members of provincial and local authorities and including listed public companies, trade unions and anti-corruption bodies in civil society.

State Capture and its exposure, said Zondo, had dominated the national discourse and “the effect has been predictable and negative”, including “a loss of confidence both in government and political parties and in the business sector compounded by frustration at the pervasive lack of accountability for wrongdoing”.

It was the view of the commission that, “It is more than time to take steps to restore broken trust, and the first step which needs to be taken in that direction is for all sections of society to jointly endorse a national commitment to eliminate corruption in public life and in the procurement of goods and services.”

By way of a gesture which was both “symbolic and substantive to mark the turning of the page”, the commission recommended that a national charter against corruption incorporating a standardised code of conduct be adopted by the government, the business sector and relevant stakeholders.

With regard to whistle-blowers, Zondo said that legislation should be introduced or amended “to ensure that any person disclosing information to reveal corruption, fraud or undue influence in public procurement activity be accorded the protections stipulated in article 32(2) of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption”.

Apart from this and other measures, Zondo proposed that a litigation unit in the new anti-corruption agency “incentivise such disclosures by entering into agreements to reward the giving of such information by way of a percentage of the proceeds recovered on the strength of such information”.

He further recommended that legislation be introduced to facilitate “deferred prosecution agreements” in which the prosecution of an accused corporation can be deferred on certain terms and conditions.

These included that a company had “self-reported facts from which criminal liability could be inferred and has cooperated fully in making such report and that the company has agreed to engage in specific conduct intended to ensure that such conduct is not repeated”.

If they had succeeded in December 2015, we do not know where this country would be. If in the future such efforts will be tried, this country should have a truly independent agency.

Kicking off the comprehensive section on the proposed reforms, Zondo said that “the years of frustration teach us lessons which we cannot ignore”.

These included the realisation “that the public procurement sector cannot defend itself against those who control the levers of political and state power”.

Also, “the excessive decentralisation” of a sprawling procurement system which had “outrun the collective capacity to manage or operate it efficiently” as well as “the absence of the robust, detailed and intrusive monitoring of the system undoubtedly facilitates corruption and inefficiency”.

The exclusion of “meaningful private sector involvement” in the formulation and implementation of policy “weakens the procurement system, lessens its transparency and facilitates corruption”, he said.

An absence of accountability “makes the system unworkable, corrupts those who operate within that system and establishes and embeds criminal relationships involving commercial entities and public officials and implicates political party funding”.

In order for the anti-corruption agency to do its work effectively, it would be necessary to “ensure that the adequacy of its funding is proof against political interference”.

This could be achieved, said Zondo, by protections built into enabling legislation and by providing for sources of revenue additional to parliamentary funding.

“In leading the fight against corruption, the agency will be providing an essential service for both the public and the private sectors and both should contribute in some appropriate way to its funding.”

In that regard, he said, “There should be no objection to the imposition of a levy payable to the agency by every person seeking a procurement contract or participating in a tender process. This will provide the agency with necessary additional funding beyond that supplied by Parliament and other sources.”

The commission appreciated that the establishment of the agency to lead the fight against corruption in public procurement required “an adjustment and realignment in the functions of National Treasury which exercises the overall supervisory jurisdiction in public procurement matters”.

The commission was also aware that the National Treasury had published a draft Public Procurement Bill, 2020, which contained “far-reaching proposals to reform public procurement”.

These suggested reforms included the establishment of a Public Procurement Regulator within the National Treasury who would exercise “considerable statutory powers”.

Evidence heard by the commission with regard to the National Treasury was that between 2014 and Zuma’s resignation as president of South Africa in February 2018, “serious efforts were made by the Guptas, assisted by President Zuma, to capture National Treasury.

“If in the future a similar attempt were to happen, there is no guarantee that the effort to capture National Treasury will not succeed,” said Zondo.

“If they had succeeded in December 2015, we do not know where this country would be. If in the future such efforts will be tried, this country should have a truly independent agency.” DM

[hearken id="daily-maverick/8976"]