The first time I met Garth Owen-Smith was in 1983. I was a young newspaper correspondent based in Windhoek covering the bush war in Namibia for the SAAN Morning Group of newspapers, including the Cape Times and Rand Daily Mail. It was over morning coffee at Café Schneider. A tall, skinny, softly spoken, bearded man wearing faded jeans, a khaki shirt and Swakopmund kudu-skin veldskoen with no socks walked up.

“People tell me you’re not scared of the apartheid government,” he said. “Do you want to come to the Kaokoveld?”

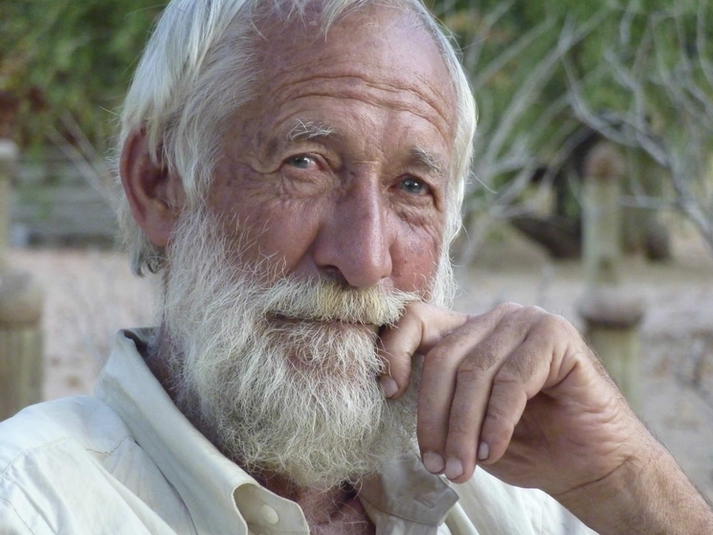

Garth Owen-Smith was rightly regarded as being the father of on-the-ground community-based conservation in Africa. (Photo: Neil Jacobsohn)

Garth Owen-Smith was rightly regarded as being the father of on-the-ground community-based conservation in Africa. (Photo: Neil Jacobsohn)

That was the start of a friendship, and (I like to think, anyway) a mentorship that continued for nearly 40 years, until his death from cancer early on Saturday, 11 April 2020. His long-time partner and collaborator, Dr Margaret Jacobsohn, emailed me on February 20 to tell me he wasn’t well, that the cancer had spread. I emailed back: “I’m not sure if he knows this, but the conversations he and I had around fires in the Kaokoveld back in 1983/4 and later were what shaped my own conservation and environmental philosophy, and have done so ever since, particularly on community-based conservation. In conversations, I always cite him as the most influential person on my thinking.”

Garth’s uniform of faded jeans or khaki longs, khaki shirts and kudu skin vellies seldom changed, except when he had to reluctantly uproot himself from the bush to attend conferences, meetings with government officials, or to fly off to international award ceremonies.

In December 2015, Garth pulled off what must be a world first – he wore a pair of Swakopmund kudu-skin vellies to Kensington Palace to meet the Duke of Cambridge, Prince William. He and Margie were in London at the Tusk Awards to receive the Prince William Award for Conservation in Africa.

Garth Owen-Smith and Margaret Jacobsohn with the Goldman Prize. (Photo: suppiled)

Garth Owen-Smith and Margaret Jacobsohn with the Goldman Prize. (Photo: suppiled)

In 1993, he and Margie flew to San Francisco to receive conservation’s equivalent of the Nobel, the Goldman Prize. In the video of his acceptance speech, he is clearly wearing kudu-skin boots. The Goldman organisation’s video tribute to him and Margie is memorable.

The Goldman citation reads in part: “Garth Owen-Smith and Margaret Jacobsohn pioneered a natural resource management program that links Namibian wildlife conservation to sustainable rural development, which has since become a model for wildlife conservation throughout Africa… Together, Owen-Smith and Jacobsohn have brought reason for hope and optimism in rural Namibia: most wildlife species have increased in the northwest Kunene region and in Caprivi, in the northeast of Namibia, poaching is being brought under control with major input from community-appointed game guards.”

Garth was rightly regarded as being the father of on-the-ground community-based conservation in Africa. After that first coffee at Windhoek’s Café Schneider, we travelled together to Namibia’s remote north-western Kaokoveld on an anti-poaching patrol, starting from his isolated base in Damaraland, Wêreldsend. It was the beginning of my real environmental education. Garth was the finest naturalist I have known, with an encyclopaedic knowledge of his landscape and its inhabitants.

Tony Weaver at Etanga, Kaokoveld, 1984. (Photo: Julia Singer)

Tony Weaver at Etanga, Kaokoveld, 1984. (Photo: Julia Singer)

Despite never getting a formal degree (he abandoned both attempts, one in agriculture, one in zoology), he was widely recognised both in academia and in conservation circles as a world expert in his field and a posthumous honorary doctorate would not be misplaced.

On that first journey, we spent hours around the fire at night, Garth talking of his vision, me scribbling notes by the firelight, often with hyenas whooping in the background, or the distant roar of a – at that time – rare desert-adapted lion.

We were headed through the Marienfluss to Otjinungwa on the banks of the Kunene River, where Garth stood crocodile watch with a loaded shotgun as I fished for supper. By then we had eaten the two live goats we had traded for bundles of rough Purros tobacco along the way, and which travelled for miles with us, bleating on the back of Garth’s Land Rover.

We saw only one other vehicle in nearly a month’s travel, the faded drab green Land Rover Series IIA shortie driven by the late Blythe Loutit, who founded the Save The Rhino Trust.

The Kaokoveld is a place of endless vistas across lichen-covered gravel plains, of rich grasslands that stand shoulder high after good rains, of soaring mountains in an astonishing number of shades of red, black and dark brown. It is a harsh land where conservation victories have been won in small increments, a place so empty the emptiness starts to move.

We scored two small victories on that journey. There were almost no tracks in the wilderness back then, and when we came across fresh vehicle spoor, we followed it. We picked up fresh tracks (they last forever on the lichen plains) just south of the Marienfluss and followed them to a recent bush camp on the banks of a dry river. “I know those tyres,” Garth said, “they belong to (a butcher from a small town not far from Etosha). He’s really stupid, but a nasty piece of work, in with the local cops and military.”

We began searching the campsite for clues, kicking over the fire, with Garth’s assistant and interpreter, Elias Tjondu, an expert tracker, casting about for any tell-tale spoor. Behind a dead log that had been dragged up to the fire to serve as a bench, a flash of familiar red and yellow half-hidden, a roll of exposed Kodak film.

Garth had the film developed, there were photographs of the butcher with his prizes – gemsbok, zebra, and a black rhino. Armed with the evidence, Garth laid charges. But this was war-time Namibia, the butcher was an influential white man in a frontline town, he was friends with the police, the magistrate, the nature conservation officials, a reservist in the local commando. He got away with a slap on the wrist – but it was a good warning to the band of white hunters who had until then regarded the Kaokoveld as their happy hunting ground.

The second small victory was gained after we had negotiated our way across what has now become a notorious challenge for 4x4 adventurers, Van Zyl’s Pass, but what was then just another part of the track, and down to the village of Etanga. There Garth was trying to woo the headman of the Orupembe district, Vetamuna Tjambiru, into joining the community game guard and conservation scheme he was patiently stitching together. Garth was a master negotiator, patient, respectful, informed.

Around the fire, Garth had taught me about Himba customs and taboos: whenever we arrived at a new village, our first ritual was to place a stone on the graves of the ancestors as a sign of respect. The second was to never cross between the chief’s hut and the sacred mopani fire which is kept burning in perpetuity.

The fire symbolises a living link between the present and the past, between those still alive and the spirits of the ancestors. Allowing it to die is an insult to the ancestors, and a severing of links to the spirit world. It was this link that was vital in the wooing of Chief Vetamuna Tjambiru.

I have an old Kodachrome slide of Garth and Chief Vetamuna Tjambiru sitting under the shade of a giant acacia albida, an ana tree. The chief is leaning forward, his chin on his walking stick as he talks. I wrote down his words as Elias translated: “When I see the wild animals, my heart is happy, they are like my children, my cattle. When there are no wild animals, my heart is sad. It is as though the graves of my ancestors have been destroyed, my sacred fire extinguished.”

It was a big breakthrough, a vital cog in establishing a network of community-based wildlife conservation projects that today underpins Namibia’s entire wildlife philosophy.

Back then, Garth was waging an almost single-handed low-intensity war against the apartheid-era Namibian authorities who treated wild areas and the wildlife as their own personal property, and had complete disdain for local, black communities.

Poaching was rampant. Some of it was survival hunting by local subsistence hunters, but there were also organised rhino horn syndicates at work, some operating out of the military and the police.

Garth was intensely disliked by the apartheid authorities, who saw him as a subversive and a sympathiser with the Swapo guerilla movement. At one stage, he was banned from entering the Kaokoveld because he was “a security risk”. And he was a subversive, but not in the way that they believed – he was simply a humanist with a strong liberal philosophy who passionately believed that local communities owned their wildlife, as opposed to the view of the white authorities, who saw them as a primitive obstacle.

He had no official funding and survived off occasional grants and remittances from organisations like the far-sighted Endangered Wildlife Trust. He was on the bones of his arse. He drove a battered Series III Land Rover with tyres that were through to the canvas. When we visited we would take along whatever we could manage to scrounge. His own binoculars were a battered pair of old Pentaxes with one eye cup missing. I felt embarrassed to own a new pair of Nikons.

By late 1984, I was also “stringing” – in media terms, someone on the ground with local knowledge who contributes information and reports, seldom bylined – for among others, Newsweek and The New York Times. The Times asked me to “help facilitate” a visit to Namibia by one of their correspondents, Jane Perlez, and her partner who was writing for The New Yorker, Raymond Bonner (both went on to win Pulitzers).

I had leave due, so offered to take them on a trip to Damaraland and the Kaokoveld, and to spend time in the field with Garth. There was one proviso – I didn’t want a fee, but had a shopping list of goods. Thus it was that Perlez and Bonner filed one of their more unusual expense accounts – two 750x16 Land Rover tyres; four steel jerry cans, filled with petrol; a Land Rover starter motor; a case of bully beef; two sleeping bags and a tent (donated to the game guards after their short use); and a pair of new binoculars.

Partly based on his experiences in the Kaokoveld and his many conversations with Garth, Bonner went on to write a controversial, and ground-breaking book on African conservation, “At the Hand of Man: Peril and Hope for Africa’s Wildlife”.

Much has, and much will be written about the life and times of Garth Owen-Smith, his is a many-layered story. I have so many memories: of Garth loping silently across the desert plains, “like an old elephant”, my wife Liz said; Garth carefully picking up scorpions and moving them to safety after unseasonal rains drove them towards our fire – and then, after 30 or more had invaded our space, and one had tried to climb up Liz’s leg, saying “bugger this” and beating them to death with a spade; a flight of Namaqua sandgrouse, kelkiewyn, flying overhead in late afternoon and Garth saying “if you’re ever stranded without water, follow the kelkiewyn, they fly straight to water three hours before sunset”; Garth always building a small fire, never a bonfire, feeding one stick at a time, point first into the fire in the Himba way – “deadfall wood is a crucial desert habitat for myriad creatures, big fires destroy habitat”; Garth carefully doing a 10-point turn in his Land Rover when surrounded by endless miles of seemingly dead desert, because “these ancient and fragile lichen plains are one of Earth’s oldest life forms, just one pass of a set of vehicle tracks will still be here in a hundred years.”

We drove together down the river bed of the Upper Hoanib, the Khowarib Schlugt – the southern border of the Kaokoveld – a place of legends. It is a magnificent gorge fringed on all sides by towering red cliffs. At odd intervals in the river, perennial springs pop up to the surface, running for a few hundred metres before disappearing underground again.

Halfway down the Schlugt is a towering ana tree. We stopped in its shade to brew some tea, we were sitting under “Oom John se Boom”, Uncle John’s Tree. Garth told the story: in the 1970s, when South Africa was tightening its military grip on Namibia and Angola, the South African Prime Minister Balthazar John “BJ” Vorster came here on hunting trips. There were more elephant and black rhino than could be counted. Lions moved through the long grass and the gemsbok were thick as cattle.

Vorster was no longer the strong young man he used to be. He was hoisted onto a broad platform in a fork of the ana tree where two mighty branches split skyward. Then the South African Air Force helicopters scoured the side gullies of the canyon for elephant, herding them down into the Schlugt. As they panicked and stampeded down through the fine powder dust of the gorge, John Vorster picked them off with his hunting rifle.

Vorster and his Cabinet colleagues had a hunting camp on the banks of the Kunene River, one of the last refuges of the endangered black-faced impala. Vorster and his Cabinet cronies hunted them down with semi-automatic rifles, they were gathered into nets slung below Air Force helicopters and flown to the camp where they were sliced into strips and hung in the sun to dry as biltong.

Much as he hated indiscriminate killing, Garth was never opposed to hunting as an important source of conservation funding: “Trophy hunting is an essential part of conservation, particularly in areas where photographic tourism isn’t possible. It is integral to our programme.”

‘An Arid Eden: A Personal Account of Conservation in the Kaokoveld’ (Jonathan Ball).

‘An Arid Eden: A Personal Account of Conservation in the Kaokoveld’ (Jonathan Ball).

In 2010, Garth published his life’s work: “An Arid Eden: A Personal Account of Conservation in the Kaokoveld” (Jonathan Ball). I reviewed it at the time and wrote:

Once in a decade, an African memoir or novel comes along that instantly goes onto my “classics” shelf. They are few and far between: Isak Dinesen’s (Karen Blixen) Out of Africa; Bernhard Grzimek’s Serengeti Shall Not Die; Jomo Kenyatta’s Facing Mount Kenya; Ernest Hemingway’s The Green Hills of Africa; Jane Goodall’s In the Shadow of Man; George Adamson’s My Pride and Joy; Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth; John Hillaby’s Journey to the Jade Sea; Wilfred Thesiger’s The Life of My Choice; Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Petals of Blood; and Elspeth Huxley’s The Flame Trees of Thika are among them.

“An Arid Eden” goes straight to the “African classics” shelf.

This is one of the most important books on African conservation in several decades. And while it deals with just one region of Africa, Namibia’s Kaokoveld, its lessons and conclusions are universal throughout the continent.

“An Arid Eden” is a monumental work, a detailed account of his almost 50 years in the field in Namibia, battling, often against almost insurmountable odds, to get conservative authorities to recognise that conservation could not be imposed on remote rural communities from afar. The answer, he tirelessly fought for, was to make the local communities the guardians of their land.

The end result is evident throughout Namibia today: a network of community-owned conservancies that make up the Namibian Community Based Tourism Association (Nacobta), and the groundbreaking, and internationally emulated Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC) network…

Namibia’s Kaokoveld is one of the most beguiling and magnificent wild areas of Africa. Now, at last, the definitive book has been written on its modern history by the man who is not only central to that history but helped to shape the destiny of the region. “An Arid Eden” is essential reading for all lovers of Africa and its wild places.

On Easter Monday Margie e-mailed me: “Just 12 hours before Garth died, and as he was slipping into a coma, it rained at Wêreldsend for the first time in five years.”

The desert gods were weeping.

There is an old Ghanaian saying borrowed by Maya Angelou — when someone important dies, “A Great Tree Has Fallen.”

It is often a lie. This time it is true.

Safari njema, Mzee Garth, lala salama. DM

An Arid Eden cover

An Arid Eden cover