In December 2024, Palestinians in Gaza were asked: “If a ceasefire was called, what’s the first thing you would do?” “If the war stops, (the) other endless wars will begin – the search for the missing, burying the martyrs, the postponed grief,” Ahmed Hijazi said.

In Iraq, forensic anthropologists are hard at work documenting the remains of one million people, with the aim of identifying bodies through the help of DNA analysis, and returning them to families searching for their loved ones still missing after decades of conflict.

In Europe, a recently established network of forensic scientists – the Migrant Disaster Victim Identification Project – is developing “new practical methods for identifying deceased migrant disaster victims and to create a collaborative process between identification professionals and families of missing migrants”. The scale of the project is enormous: an estimated 25,000 people have died in the past 10 years crossing the Mediterranean alone, with only a quarter ever formally identified.

Here in South Africa, by 2022 the National Prosecuting Authority’s Missing Persons Task Team had reportedly recovered the remains of 179 missing people, 167 of whom had been identified and returned to their families. The task team was established following the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission with a mandate to trace the fate and whereabouts of those who disappeared in political circumstances between 1960 and 1994.

What all of these have in common is an unquenchable yearning for answers about their loved ones by those who are left behind when people disappear, whether through political violence or by the humanitarian crisis of migrants trying to reach Europe by sea or by disasters caused by climate breakdown or in many other ways.

This yearning has a clinical term: ambiguous loss.

Its principal theorist is Dr Pauline Boss, author of Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief and professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota. Boss established the psychological condition in the 1970s, defining it as “an unclear loss”.

As she told America’s National Public Radio: “Ambiguous loss is a situation that’s beyond human expectation. We know about death: It hurts, but we’re accustomed to loved ones dying and having a funeral and the rituals. With ambiguous loss, there are no rituals; there are no customs. Society doesn’t even acknowledge it. So the people who experience it are very isolated and alone, which makes it worse.”

In February, a very special project that puts ambiguous loss directly in the spotlight will have its world premiere at the Homecoming Centre in District Six, Cape Town.

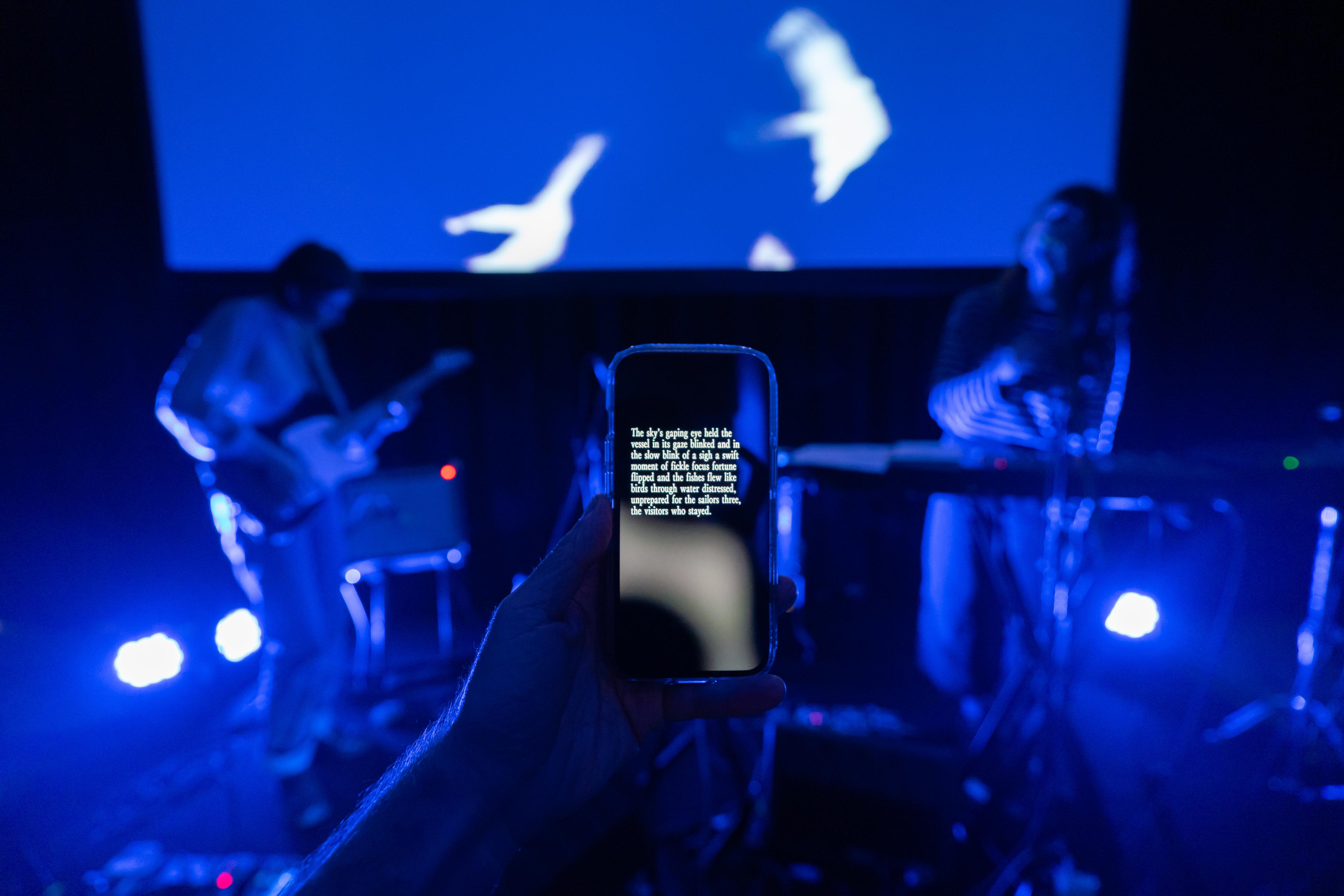

Requiem for the Impossible is a music and interactive technology experience that will be performed on stage by internationally acclaimed musicians, South Africa’s Lucy Kruger and the Netherlands’ Liú Mottes on February 13, 14 and 15.

It blends an entirely new original score (the requiem) with documentary-style voice recordings, poetry and interaction through a dedicated phone app that – importantly – allows the audience to be part of creating the experience.

The project is by award-winning, Amsterdam-based creative studio and research practice, affect lab (founded by South African Natalie Dixon) and is produced in Cape Town in collaboration with a Netherlands-based but South African-rooted music company, The Good Times Co.

I am proud to be the initiator of Requiem for the Impossible, although I would not wish the circumstances in which this came to be on anyone.

As some of you might have read previously – in two pieces of formidable long-form journalism for Daily Maverick by Kevin Bloom – a decade ago my family was plunged into a nightmare when my brother-in-law, Anthony Murray, disappeared at sea.

He wasn’t alone when this happened: on board with Anthony, the yacht’s skipper, was first mate Reginald Robertson and deck hand Jaryd Payne. The three were working sailors, on a delivery trip from Cape Town to Phuket, Thailand, when all contact was lost with them on 18 January 2015, just over a month after they had departed from Cape Town’s V&A harbour.

For more than a year we desperately searched for our loved ones – three families thrust together through an experience so singular that when I sought help from a Johannesburg grief psychologist for the anguish my family was going through, she confessed that she had never encountered anything like it before.

I never returned.

The families of Reg and Jaryd – strangers until that moment – were now the only people on Earth who shared and could understand precisely what we were going through; what it felt like to be consumed by looking for an object not more than 13m in length, in one of the world’s biggest bodies of water, hoping that a brother, a father, a son were still on board, alive; feeling the rising tide of despair as the seconds, hours and days ticked by, acutely aware from the expert sailors who helped us fathom the hitherto foreign terrain of the sea that every passing moment increased the size of the search area 10-, hundred-, a thousand-fold.

As the months went excruciatingly by, alongside the sailors (many of whom had sailed with Anthony) we were supported and helped by the Facebook community we had started, filled with beloved friends and family but also many thousands of kind strangers from across the world who, at one point, joined us in spending many hours poring over Tomnod satellite images as part of an online search party.

It’s impossible to go into all the details of our unrelenting efforts to find our loved ones here but on 18 January 2016 – incredibly, exactly a year to the day after the last known contact with the yacht – the commander of a Brazilian navy ship reported seeing an overturned catamaran hull 113 nautical miles off Cape Recife, near Gqeberha.

Unbelievably, it had floated many thousands of miles from last known contact, deep in the Indian Ocean. At the urging of the families and with the help of our Facebook community, dedicated volunteers from the National Sea Rescue Institute (NSRI) launched a sea rescue craft and placed a tracking device on the overturned hull when it was just off Cape Agulhas.

More ceaseless mobilising was demanded of the families, and we finally got the maritime authorities to agree to send a tug to bring the catamaran back to Cape Town. We believed that we were within touching distance of getting at least some answers about what happened to the three sailors.

Crushingly, however, just 10 days after it was sighted off South Africa, the hull sank to the bottom of the ocean.

The families could never properly understand why the overturned hull was lost by an experienced crew during the tow into Simon’s Town harbour. But we do know – so acutely it can still take our breath away – about the isolation and loneliness that was brought on by living between the hope that the three sailors were still alive, miraculously having made it to an isolated piece of land, and the hopelessness that they were gone forever.

This is what Boss captured when she coined the term ambiguous loss.

Until then, nothing accurately described this particular state of grief; nothing had set out what it feels like to be denied the rites of death which, painful as they are for anyone, enable those left behind to be held in an unambiguous communal embrace; until Boss’s work, nothing could help explain what it feels like to ask a court to declare the one you love dead so you can deal with his now unravelling financial life, a cruel process that requires you to hold some sort of memorial service, a pantomime of the real thing, even while you hold onto hope that he will one day sail back into Cape Town harbour.

Anthony, Reg and Jaryd have not been seen since they set sail in December 2014, but those attending Requiem for the Impossible will hear Anthony’s voice during the performances.

In the years before he disappeared, he and I began working on a book about his decades of adventures as a delivery skipper. I hoped to capture what it takes for a human to set out, in a small vessel, on a blue ocean crossing, time and time and time again.

I encouraged him to take a Dictaphone on his delivery voyages, using the downtime to capture his memories which I would then turn into a book that we gave the working title of The Life of the Rock n Roll Pirate.

Requiem for the Impossible. Taken at the pilot run of the project in Amsterdam in July 2024. Musicians: Lucy Kruger and Liú Mottes, guitar. (Photograph: Anisa Xhomaqi)

Requiem for the Impossible. Taken at the pilot run of the project in Amsterdam in July 2024. Musicians: Lucy Kruger and Liú Mottes, guitar. (Photograph: Anisa Xhomaqi)

This rare, recorded archive holds the everydayness of life aboard a delivery catamaran: the slapping of the sails in the wind, the creaking of the yacht, the voices of the crew discussing what to eat for lunch and how to keep the furnishings protected for the client they were delivering for. And, in something that never ceases to bring me to tears, alongside plenty of stories about his adventures on sea and in port, it also holds Anthony’s unadorned love, respect and veneration of the ocean – and how that acts as a prism for his awe at the very act of being alive.

Along with several deeply moving poems written by Anthony’s brother, Jay Savage, Requiem’s two musicians, Lucy and Liú (of Lucy Kruger & The Lost Boys) have woven a selection of these recordings into the breathtakingly beautiful music they have created especially for the project.

Anthony’s reflections are part of what makes the experience of Requiem ultimately a spiritually rich and mystically joyous one for the audience.

Like everyone involved in bringing Requiem for the Impossible to life, Lucy and Liú approached the project with a reverence for our experience that has been extraordinary, and Jay calls their contribution “the very anchor” of the project.

It is gratifying to us that those who are unable to be at the Cape Town premiere will be able to listen to the recording of Requiem on all streaming platforms from mid-February and, hopefully, attend additional performances in different cities across the world in the coming months and years.

In this way, and through the book I will still write, Anthony’s words and voice and life experience are not lost.

While very personal in its conceptual gestation, Requiem is, in the end, a thorough – and affirming – grappling with what Nick Cave in Faith, Hope and Carnage calls the ultimate and inescapable universal human experience: the experience of grief.

A final note: Pauline Boss later expanded her definition of ambiguous loss from situations where there is a physical absence with psychological presence, as in our situation, to ones where there is a psychological absence with physical presence, as with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

With this widening definition, it is clear: ambiguous loss affects many more of us than I could ever have imagined when a beloved friend first found Boss’s work and shared it with me a decade ago. DM

Requiem for the Impossible will be presented at the Homecoming Centre (formerly Fugard Theatre) on Thursday, 13 February at 8pm, Friday, 14 February at 8pm and Saturday, 15 February 2pm and 8pm. You can buy tickets here.

Requiem for the Impossible (Photograph: Anisa Xhomaqi)

Requiem for the Impossible (Photograph: Anisa Xhomaqi)