A study by Duke University shows how rising global temperatures will affect labour productivity, estimating global economic losses of up to $1.6-trillion dollars annually in a 2°C warmer world.

Dr Luke Parsons, a climate researcher at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment, who led the study, told Daily Maverick, “Our work suggests that global warming and associated increased heat exposure are already impacting labour productivity and potential economic productivity.”

The study found that, “Each year sees nearly $670-billion (purchasing power parity-adjusted international dollars or 2017 PPP$) are already lost each year in the 12-hour workday.”

Purchasing power parities (PPP) are defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development as: “The rates of currency conversion that try to equalise the purchasing power of different currencies, by eliminating the differences in price levels between countries.”

This study calculated that figure using PPP$ from the year 2017.

As the planet continues to warm, impacts on labour productivity and the economy will only magnify and accelerate.

“The globe is already over a degree warmer than a century ago, which is impacting workers now,” said Parsons. “Every additional degree of climate change limits people’s ability to safely support themselves and their communities.

“Additionally, critical jobs, such as agricultural work and construction work, will become almost impossible in the summer in many places.”

Economic impact of global warming

The peer-reviewed study, which was funded by Nasa and came out on 14 December 2021, found that current and projected economic costs of heavy labour losses are substantial.

“Future warming will exacerbate heat exposure, magnifying these impacts on labor productivity and the economy — these impacts accelerate with each additional degree of global warming,” said Parsons.

The study estimated a $1.6-trillion (2017 PPP$) annual loss in the 12-hour workday in a 2°C warmer world.

If this estimate seems too big to believe, Parsons calculated that already we’ve seen substantial global labour losses from the 1°+ warming seen since pre-industrial levels.

“I assumed the numbers would be large given some previous estimates, but didn’t expect them to be this large — the amount of potential productivity lost is hard for me to comprehend,” said Parsons.

“Heat exposure could already be associated with global losses in the hundreds of billions of dollars — we estimate up to about $670-billion — every year, and these numbers increase faster and faster with each additional degree of global warming.”

Additionally, the researchers found that in the 42 years from 1979 to 2020, about 101 billion hours per year of additional work were lost in the 12-hour workday per degree of global warming.

The study also calculates labour lost due to heat exposure for +1°C, +2°C, and +4°C (relative to the present) of additional global warming.

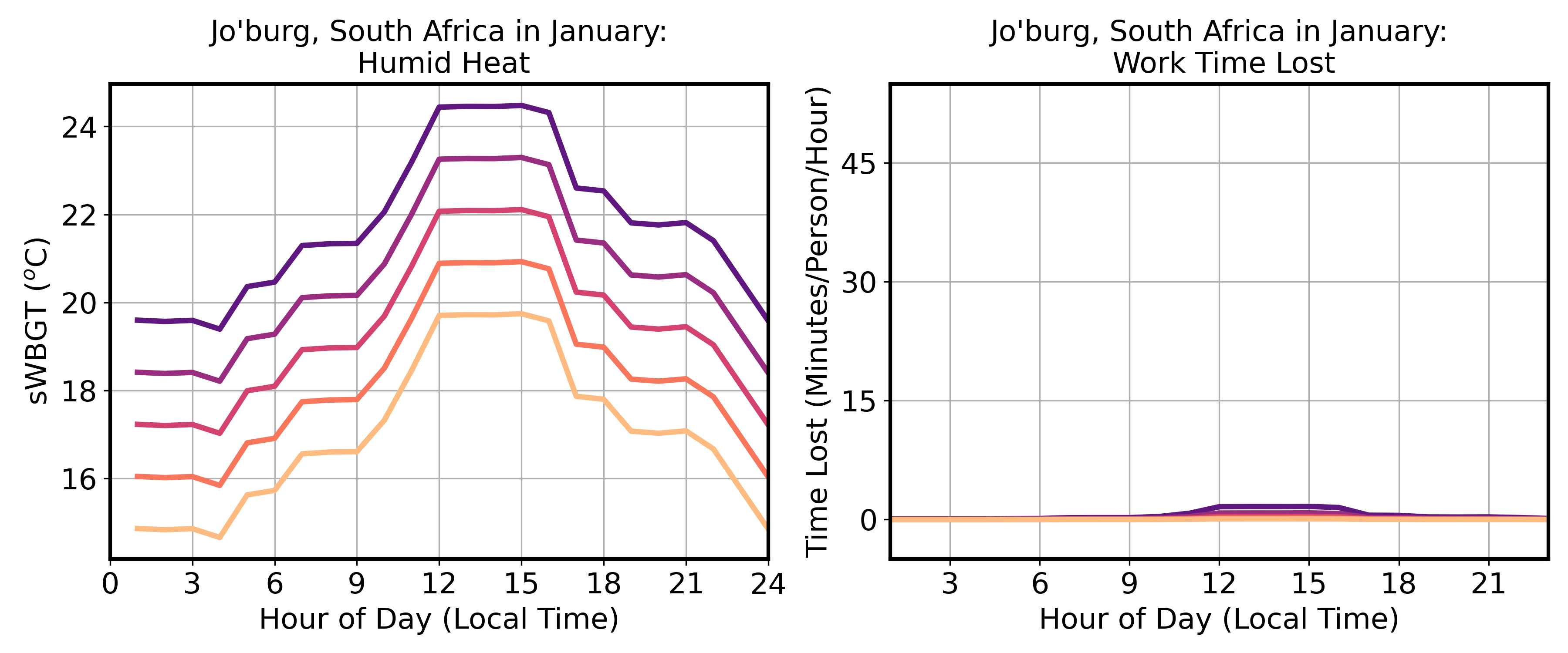

The bottom line (yellow) shows current average conditions in January (average conditions 2001-2020), and each line above it shows the impact of one additional degree of global warming in Johannesburg.

The bottom line (yellow) shows current average conditions in January (average conditions 2001-2020), and each line above it shows the impact of one additional degree of global warming in Johannesburg.

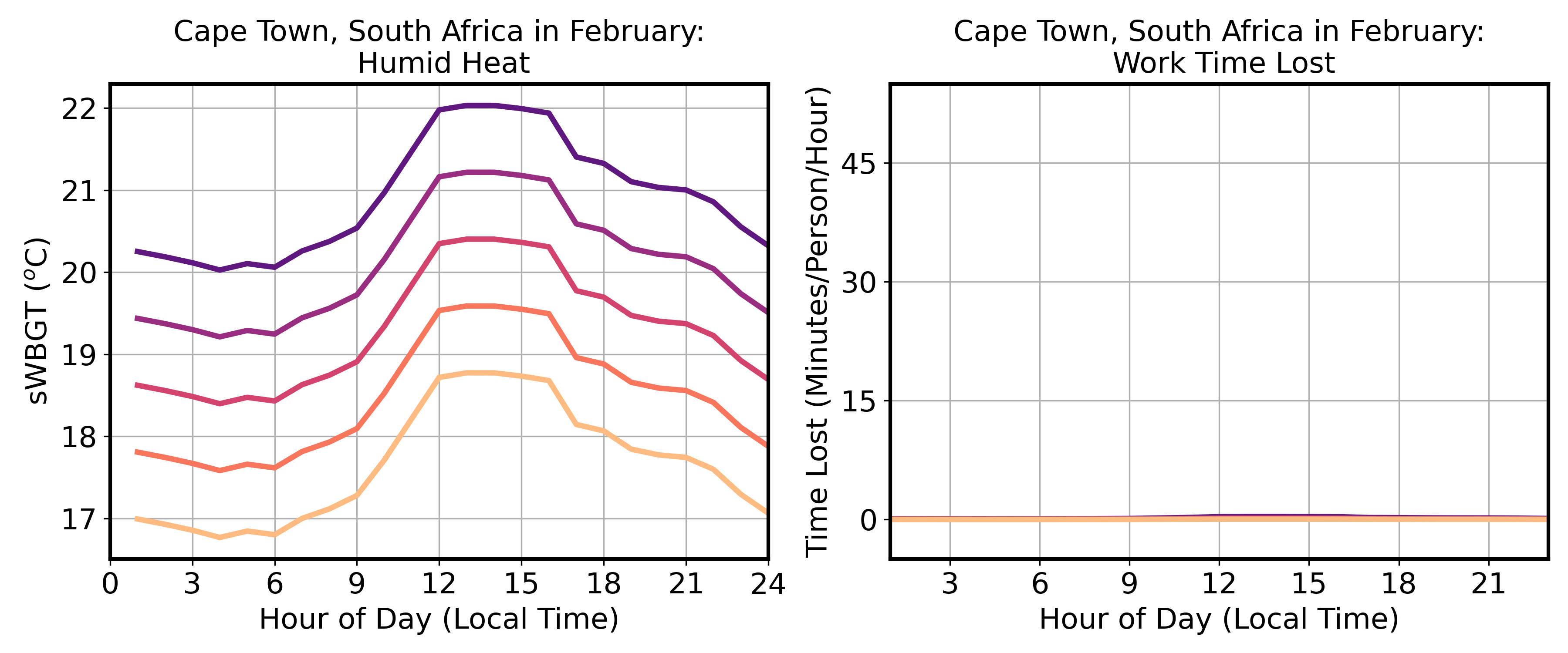

The bottom line (yellow) shows current average conditions in January (average conditions 2001-2020), and each line above it shows the impact of one additional degree of global warming in Cape Town.

The bottom line (yellow) shows current average conditions in January (average conditions 2001-2020), and each line above it shows the impact of one additional degree of global warming in Cape Town.

“Importantly, the graph on the right shows the average work time lost per hour according to a study based on workers acclimatised to hot and humid working conditions in mines and rice fields,” said Parsons.

When is this going to happen?

Parsons says when this type of warming will occur is uncertain.

“ ‘When’ depends on how quickly we continue to emit greenhouse gases, and how quickly the globe warms as a result of greenhouse gas emissions,” said Parsons.

“We specifically chose to focus on impacts at warming levels (not specific years) due to this uncertainty — when this warming will happen is uncertain, but how, spatially, the climate changes at +2 or +3 degrees is more certain.”

However, Parsons explained that under a rapid climate change scenario (the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway, or SSP, 3-7.0 used in the IPCC sixth assessment report), an additional 1°C of global warming relative to the present (defined as 2001-2020 average) could occur as early as 2037, and another 2°C of global warming could occur as early as 2051.

Adapting to heat is not always an option

“These losses are often impacting those who can least afford not to work, and as we show, workers’ ability to adapt to warming by moving work to cooler hours becomes less effective as the morning hours become too hot for continuous labour as well.”

Parsons explained that many workers in hot and humid locations have already stopped or slowed work in the hottest hours of the day. There are also studies that suggest these workers move labour to the early morning hours to adapt to a warming world.

“However, we show that this adaptation mechanism loses effectiveness as the world warms — the morning hours become too hot for continuous labour in many locations,” said Parsons.

Why rising temperatures mean lost labour hours

“How people react to heat exposure is different in different situations,” said Parsons, citing three reasons based on field studies and spatial data.

Either people slow work as the temperature rises throughout the morning, or people continue high-intensity work when it is too hot — resulting in health consequences — or people stop work when it gets uncomfortably hot or if local regulations encourage labourers to stop work at a certain heat exposure threshold.

Parsons told Daily Maverick that already isolated field studies in various locations (including Indonesia, India and Central America) indicate that many outdoor workers stop work in the afternoon because it is simply too hot and uncomfortable to work.

If workers don’t regulate or self-pace during the heat they are at high risk of health implications.

“Worker productivity is linked to economic incentives, so individuals may continue to work at the detriment to their health,” said Parsons.

“If people are unable to work in cooler conditions (or choose to continue work when it is too hot), they are at higher risk of multiple health impacts, including premature death, workplace injuries, morbidity from heat-related illness, traumatic injuries, acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease.”

How did they calculate that?

Parsons and the researchers used a heat metric called “simplified Wet Bulb Globe Temperatures” (sWBGT), which Parsons explained uses both temperature and humidity to estimate how hot it feels for a person that can sweat and cool themselves.

They calculate this using meteorological data (from weather stations, or weather balloons, or data that is input into a weather model to fill in gaps between weather stations where this is missing data) which provides them with an estimate of sWBGT about every 35km around the entire globe.

“Based on previously published observed relationships between humid heat exposure and labour productivity for agricultural workers and miners, we then estimate how much potential labour would be lost due to humid heat exposure at each hour of the day for those conducting heavy outdoor labour,” Parsons told Daily Maverick.

Parsons focused on outdoor workers (those in agriculture, construction, forestry and fisheries industries), as these individuals are typically conducting work at a high intensity, which generates internal body heat.

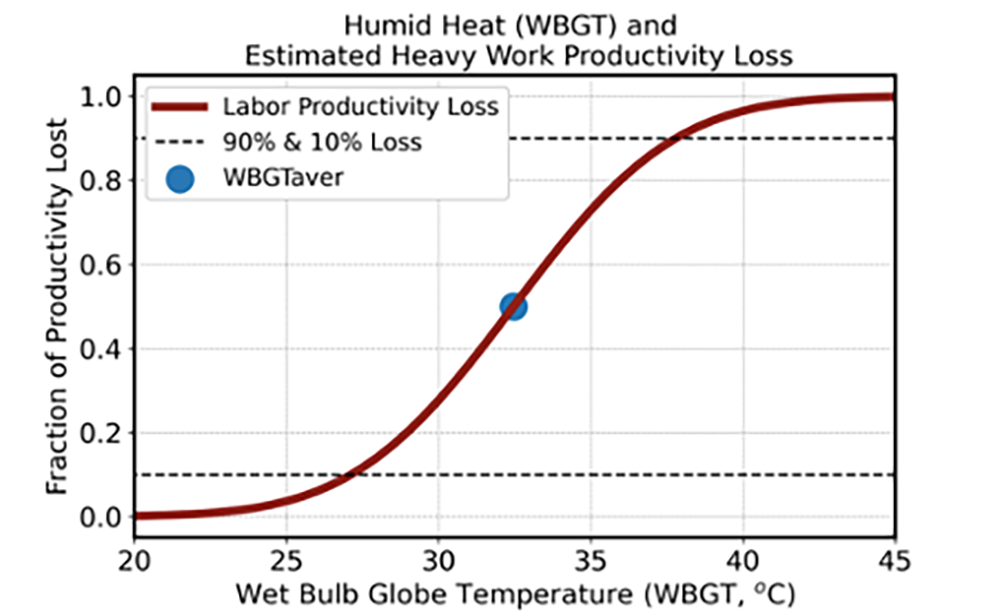

Parsons said if the sWBGT — the “feels like” temperature — is greater than about 24-25°C, then small fractions of work start being lost every hour (for workers accustomed to the heat and heavy labour), with more work lost every hour as it gets hotter and more humid.

Fraction of heavy labour productivity lost as a function of heat exposure (Wet Bulb Globe Temperatures, or WBGT) for outdoor workers.

Fraction of heavy labour productivity lost as a function of heat exposure (Wet Bulb Globe Temperatures, or WBGT) for outdoor workers.

The red line shows labour productivity loss as a function of heat exposure, the blue dot shows the ‘WBGT average’ value, and the horizontal dashed lines denote 10% and 90% productivity losses.

However, Parsons mentions that they have published a more recent study that shows that workers could be losing productivity at much lower (about 19-20°C of “feels like”) temperature, suggesting that areas in South Africa have probably already been more affected by climate change than shown in the graphs above.

To determine how many outdoor workers there are at each location, the researchers used country-level information from the International Labour Organization (ILO). They then combine these ILO estimates with spatial estimates of where working-age people live (calculated using spatial population data and spatial “feels like” temperature data to estimate how many working-age people are exposed to humid heat throughout the day) to calculate potential labour losses.

Additionally, the researchers used ILO and World Bank data to estimate how much each person in these outdoor labour sectors, on average, contributes to each country’s economy.

“Based on the labour losses above, we can calculate how much these labour losses in each economic sector would impact the economic productivity for each country,” said Parsons.

Finally, to calculate the future global warming impacts, they assumed that the hourly heat exposure goes up (each hour’s humid heat, or sWBGT, rises) under +1, +2, +3, and +4 C of additional global warming relative to the present (2001-2020), and then recalculate the average labour and economic productivity losses in the year for each of these potential future (additional) global warming levels.

Why should we care?

“I think it’s important to consider this information as we weigh the costs of climate change mitigation and our ability to adapt to a warming planet,” said Parsons.

He said that it’s important for us to recognise that heat exposure and associated labour loss have implications for health and the economy.

Parsons views these impacts as important for policymakers to consider when they weigh the costs and benefits of limiting climate change.

As with most impacts of climate change, those in the Global South, and the least emitters risk facing the worst impacts.

Parsons explained that humid heat exposure already affects a large portion of the world’s population that works outdoors, particularly at low latitudes (near the equator) — such as Africa, the Americas, and some parts of Asia.

“Many of these people are unable to move this labour into air-conditioned environments when it is hot outside,” said Parsons.

“I hope this work calls attention to how climate change is already impacting and will impact people who depend on outdoor work to support themselves and their communities — these people are often some of the most vulnerable to climate change, and the least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions.” DM/OBP

Fraction of heavy labour productivity lost as a function of heat exposure (Wet Bulb Globe Temperatures, or WBGT) for outdoor workers.

The red line shows labour productivity loss as a function of heat exposure, the blue dot shows the ‘WBGT average’ value, and the horizontal dashed lines denote 10% and 90% productivity losses.

Fraction of heavy labour productivity lost as a function of heat exposure (Wet Bulb Globe Temperatures, or WBGT) for outdoor workers.

The red line shows labour productivity loss as a function of heat exposure, the blue dot shows the ‘WBGT average’ value, and the horizontal dashed lines denote 10% and 90% productivity losses.