History is never boring — although some people can make it seem that way. Sadly, numerous universities are dropping the discipline as a major subject and — even worse — even among schools that continue offering it, the number of pupils pursuing it as their chosen field of study seems to be declining.

Paradoxically, the shelves of bookstores bulge with popular histories, biographies of famous figures, and increasingly, memoirs from political, sports and cultural figures. People buy them and read them. Why? Almost certainly it is because as humans we have a nearly insatiable desire to discover what our forebears did and what they were really like.

Among the growing pile of books on this writer’s nightstand, on a nearby occasional table, and even under that table, besides biographies and historical studies from the rest of the world such as Walter Isaacson’s biography of Albert Einstein, Boris Johnson’s autobiography, Unleashed, and Norman Lebrecht’s Genius and Anxiety, there is also a collection of works on South Africa’s history and its leading figures.

Given the country’s complex, often troubling past, it should not be a surprise that in recent years many important figures have written their memoirs and that biographers and other writers have taken up important — as well as less studied — aspects of the country’s past. Henry Ford was certainly wrong — history is not bunk.

Among those wide-ranging volumes published recently on South Africa, important titles are Patric Tariq Mellet’s The Truth About Cape Slavery, Peter Friedland’s Quiet Time With the President, Jonny Steinberg’s Winnie and Nelson, Justice Malala’s The Plot to Save South Africa, Jonathan Ancer’s biography on Harry Oppenheimer, Richard Steyn’s exploration of an earlier South African history with Rhodes and his Banker, along with Charles van Onselen’s The Night Trains, and The Cowboy Capitalist.

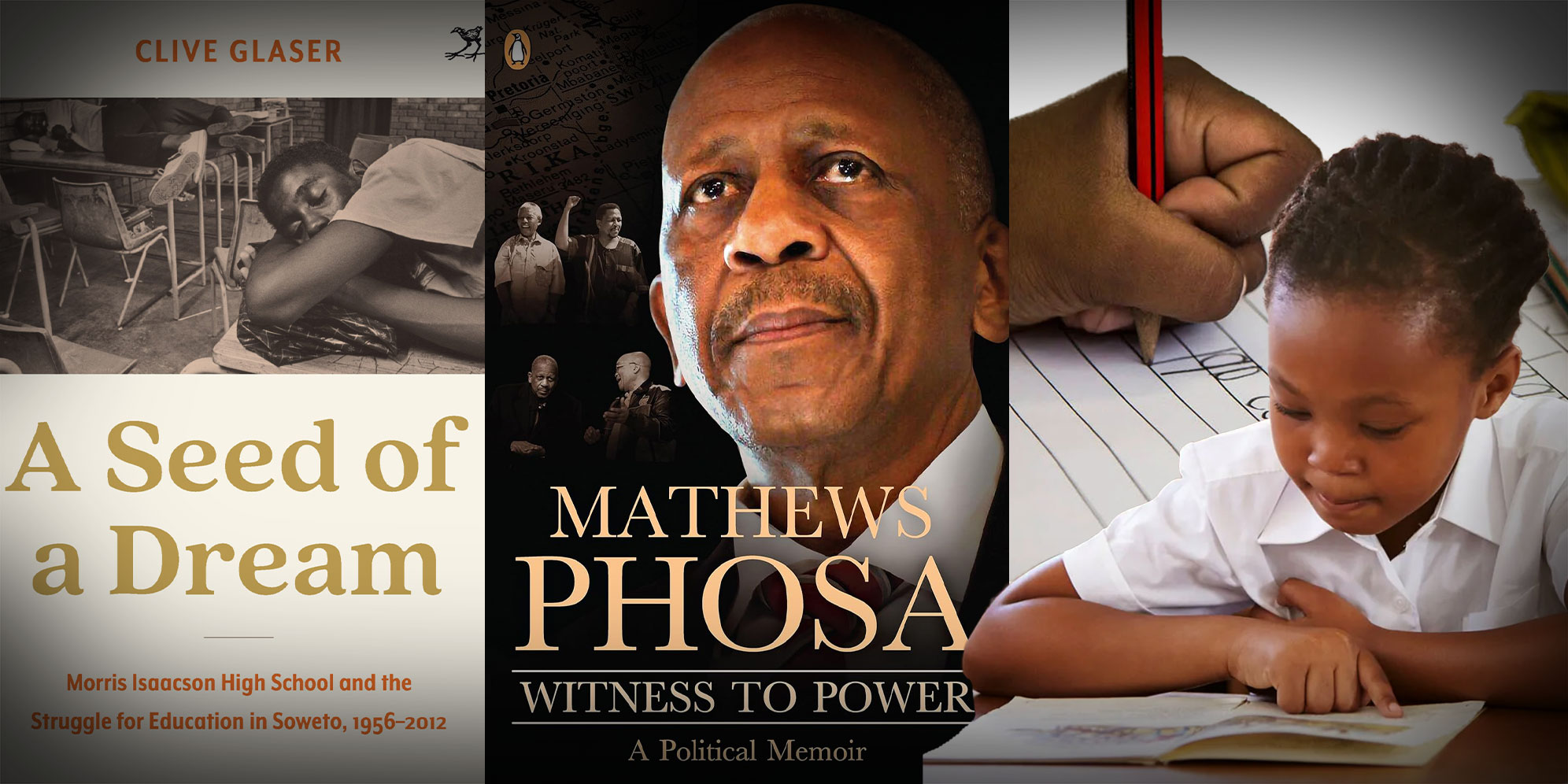

In the past several weeks, we’ve read two new books, Clive Glaser’s A Seed of a Dream — a social history of Morris Isaacson High School — and Mathews Phosa’s memoir Witness to Power. Despite their different approaches and contents, the two volumes present mutually informing overlaps that should encourage further questions and explorations of South Africa’s recent history.

A Seed of a Dream

Glaser’s book on Morris Isaacson High School looks closely at the saga of one of Soweto’s, indeed South Africa’s, most storied educational institutions. Despite its pedestrian architecture and utilitarian structures and the lack of hallowed halls creating a tangible sense of history and tradition (those pricey private schools around the country), throughout Morris Isaacson’s existence it has had a deep influence on its pupils and arguably has had an even larger impact on the trajectory of South Africa’s history as a whole.

For many in South Africa, and in the global imagination about a seminal moment in South Africa’s history as well, the school’s name is closely tied to the 16 June 1976 Soweto uprising — an event that was one of the opening salvos in a sustained struggle to bring apartheid to an end.

The organisers and leaders of that day’s march (and in the ad hoc Soweto students’ council that planned it) primarily came from Morris Isaacson (plus Orlando High School). They had been well-schooled in independent thinking and leadership skills by some serious-minded educators, going beyond the prescribed curriculum despite the strictures of “Bantu Education”. The school had a strong tradition of a debate club in addition to sports teams that often overwhelmed their competitors.

In this book, Glaser focuses preeminently on the institutional history and structure of the school, from its origins through to its recent circumstances. Like almost all the other schools offering education to Africans in a racially segregated South Africa, before the formal imposition of apartheid and the government’s subsequent hostile takeover of black education, Morris Isaacson was established by Christian missionaries; however, its expansion was underwritten by funds from a businessman benefactor, Morris Isaacson.

Read more: We have yet to reach the critical Uhuru for which class of ’76 fought and died

In the 1950s, after it was forced into submitting to the “Bantu Education” system implemented by the apartheid regime, it was something of a miracle the school’s administrators and teachers continued to imbue the school and its pupils with a sense of a larger purpose. This was despite it being part of an educational milieu designed to train Africans into becoming no more than the “hewers of wood and drawers of water”, in the words of a South African prime minister, echoing an ancient biblical curse.

Glaser sees the school’s growth, reputation and larger impact on the rapidly growing Soweto population significantly as the result of the leadership skills of a line of headmasters such as LM Mathabathe (during the early to mid-1970s) and the school’s department heads. The school’s traditions were sufficiently strong that it managed to survive, if not entirely thrive, through the political upheavals and violence of the late 1970s and then into the 1980s and 1990s.

This book has evolved out of a postgraduate research project guided by Glaser, with a coterie of more junior scholars tracking down alumni and interviewing them, as well as searching for old, often-forgotten records, official testimonies and newspaper accounts to establish a surprisingly comprehensive chronology of the school’s history and its pupils’ achievements.

One topic that might have been explored more deeply is how the ideology of black consciousness thoroughly engaged pupil discussions at the school — often via the impact of younger teachers — in the early 1970s, similar to what was happening at the University of the North at Turfloop (now the University of Limpopo).

Part of that shared approach can be read as the influence of a group of black university students from that university and several others, who had strong black consciousness leanings, and who began teaching at Morris Isaacson in the early 1970s. One interesting question remains of just how that orientation was largely supplanted among students by the Charterist thinking of the United Democratic Front (on behalf of the African National Congress) by the 1980s and 90s.

In addition, it might also have been extremely interesting if the research team had been able to follow in depth what happened later in the lives of some of the alumni they interviewed — thus a limited longitudinal study of the influences of the school. Such an exploration would have echoed what one of the school’s more recent students told Glaser: “I went to Morris [Isaacson] because of its prestige as a Soweto school. I really didn’t want to go to a Model C school [formerly white, government schools, located in better-endowed suburbs of South Africa’s big cities]. The history talks to you.”

Despite such gaps, Glaser’s volume is an important institutional history of a key organisation in South Africa — and such an approach is a model still relatively rarely followed by historians. Most seem to prefer, instead, a focus on a great man/great woman, or the explanatory straitjacket of those implacable economic forces, as their guiding stars.

Regardless, there are dozens of institutions across the nation (many of them formed by black people), including schools, stokvels, church organisations, labour groups, community associations, businesses and cultural and artistic groups, most of whose histories have been poorly chronicled or even remembered nowadays — even if primary source materials are stored in someone’s dusty garage or a mouldy backroom. Accordingly, South Africa’s historians still have vast scope for documenting stories that could be so much more than topics for rarely read dissertations.

Read more: Soweto, 16 June 1976: ‘Freedom Is Coming, Tomorrow’

Witness to Power

It was in tandem with reading and thinking about the history of Morris Isaacson as traced by Glaser and his team and how he brought its early years to life on the printed page, that Phosa’s memoir also made its way to this reviewer.

In the early chapters of this newly published memoir, Phosa offers a richly detailed, even loving portrait of his childhood in a community that was still only partially affected by the full weight of apartheid, at least during his earliest years. The young Phosa attended rural schools as he helped family members raise crops, tend livestock and engage in commercial activities, and he was motivated to excel at school work as he rose through his grades.

His academic prowess gained him entry to the University of the North at Turfloop, just as black consciousness thinking was making its influence felt there, just as what was happening with teachers at Morris Isaacson who had also attended universities like Turfloop.

Phosa and his fellow students’ protest actions against university management and its starkly segregated circumstances gained him basilisk attention from school administrators and the police, but he managed to survive, thrive, graduate and afterwards gain the support of a legal mentor who provided him with an entry-level position and encouragement to advance further in his legal studies.

What does not come through quite so clearly in Phosa’s text, however, is his own intellectual and political journey from that earlier black consciousness thinking and positions within Azapo and thereafter to the Charterist ideology and thus his surreptitious efforts with the ANC domestically and in exile in southern African nations.

What we miss in this narrative is a sustained discussion of the authors and writing that were fundamental in the evolution of Phosa’s thinking, or which professors and others were influential in shaping his thinking, other than some discussion about student colleagues who were similarly active in their black consciousness protest actions.

The remainder of the book recounts his path through and up the ANC’s structures and the people and circumstances he dealt with along that way. It is clear he was profoundly drawn to Nelson Mandela and aspects of Mandela’s political philosophy, notably his ideas about forgiveness and inclusivity.

Nevertheless, it is also clear Phosa came to have less and less regard for Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma because of their willingness to bend organisations and structures for personal whims or benefits (particularly so in the case of Zuma). Phosa despaired about the extent to which those two men drifted further and further from the ideals he believed were — or should have been — the guiding principles of the ANC’s stewardship of the nation.

Read more: Witness To Power — Mathews Phosa on how he avoided the Guptas’ honey traps

The biggest revelation in the book is his first-hand description of the illicit goings-on carried out as Libyan money flowed into the ANC’s coffers. Almost as an aside, he speculates about the possibility of some of it also flowing into the personal accounts of Zuma — although he avers he has no clear proof of the latter.

(For more on the Libyan funds, see Peter Fabricius’ recent article.)

What becomes clear from his memoir, as Phosa climbs the party ladder as a key legal expert and the party’s treasurer-general, are his descriptions of the shenanigans of so many of his colleagues, even though those descriptions become increasingly abstract and without the passion of his memories of his early years — or his idolisation of the country’s first democratically elected president. In this memoir, we never quite get to the core of what Phosa’s philosophy of governance comprises, beyond adherence to the party’s guidelines.

As the years go by, Phosa is repeatedly called upon to mediate between party factions (and once to defend himself from spurious charges that he and two others had been plotting a coup against Mbeki). But in Phosa’s discussions, such factional battles seem less to do with actual disagreements over policies, hopes or dreams, than with the jousting over party positions and power.

In those discussions, we encounter an impressive roster of meetings in restaurants and hotels, even if we rarely learn about the deeper reasons why he was being asked to mediate. It seems he has been assiduous in his diary keeping, but less forthcoming over what was decided or was at stake for his ministrations.

These disputes often seem to be squabbles between cliques within the governing party aligned with powerful individuals. Consequently, there is less contemplation about whether the challenges of governing a nation were the reason for a meeting or if there was something more tawdry at play.

There are excursions into Phosa’s love of Afrikaans and of his crafting of poetry in that tongue, including examples of his writing, but a sense of the core of the man is curiously elusive for a memoir. Too much lawyer, but not enough of the self-examining poet-philosopher, perhaps. We can hope that some day Phosa will author a more contemplative essay in which he explores his beliefs and how they were transgressed by the careerism and avarice of influential colleagues.

Taken together, despite the gaps, these two volumes offer real insights into the arcs of political consciousness for young South Africans, especially during the crucial years before 1994. Further, they provide understandings about the roles of institutions in those developments and thus point to how such things must continue to be interrogated. There remains a need for much more exploration and examination of those things by people who were there — before such developments are forgotten in a rush to embrace the simple, unexamined narrative of liberation. DM

Mathews Phosa, with Pieter Rootman, Witness to Power — A Political Memoir, Penguin Random House, 2024, ISBN 987 1 77609 395 3 (print), ISBN 978 1 77609 396 0 (ebook)

Clive Glaser, A Seed of a Dream — Morris Isaacson High School and the struggle for Education in Soweto, 1956-2012, Jacana Media, 2024, ISBN 978 1 4314 3450-3