“A large number of people who indicate they will vote, do not (vote) because of limited choice... Willingness to vote does not translate into votes – it just means greater abstentions,” said institute research Fellow Professor Rajen Govender of UCT’s Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance.

He said this trend was not confined to South Africa.

The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) found that 47% of South Africans did not feel sufficiently qualified to participate in politics, while 51% felt they lacked a good understanding of the important issues affecting South Africans.

Yet, seven in 10 were clear – politicians must follow people and people should make the important decisions.

“These results make for an uneasy mix: citizens simultaneously lack confidence in their own abilities as political actors, are distrusting of elected representatives, parties and elites, yet aspire to greater influence and more responsive leaders and institutions,” according to this latest SA Reconciliation Barometer.

The public opinion survey has run for 20 years, allowing longitudinal comparisons that track public trust in institutions.

For this latest SA Reconciliation Barometer, a nationally representative 2,006 South Africans were interviewed in August and September.

Crucially, in 2023, eight in 10 South Africans did not believe those running the country cared what happened to ordinary people. That’s a stark jump from the 50% of South Africans who believed this to be the case between 2003 and 2013.

Put slightly differently: 79% of South Africans distrust national leaders in 2023, up from 18% in 2003 and 21% in 2013.

Meanwhile, confidence levels in political parties show the ANC at 37%, and the DA at 25%. Only the EFF is bucking the trend, with confidence levels rising to 32% in 2023, up from 20% in 2017.

Crucially, blooming support for the EFF is also reflected in the survey question on closeness to a political party – 18% declared closeness to the EFF, up from 11% in 2011, while the DA remained static at 13%. The ANC dropped to 37% declared closeness, from 43% over the same period.

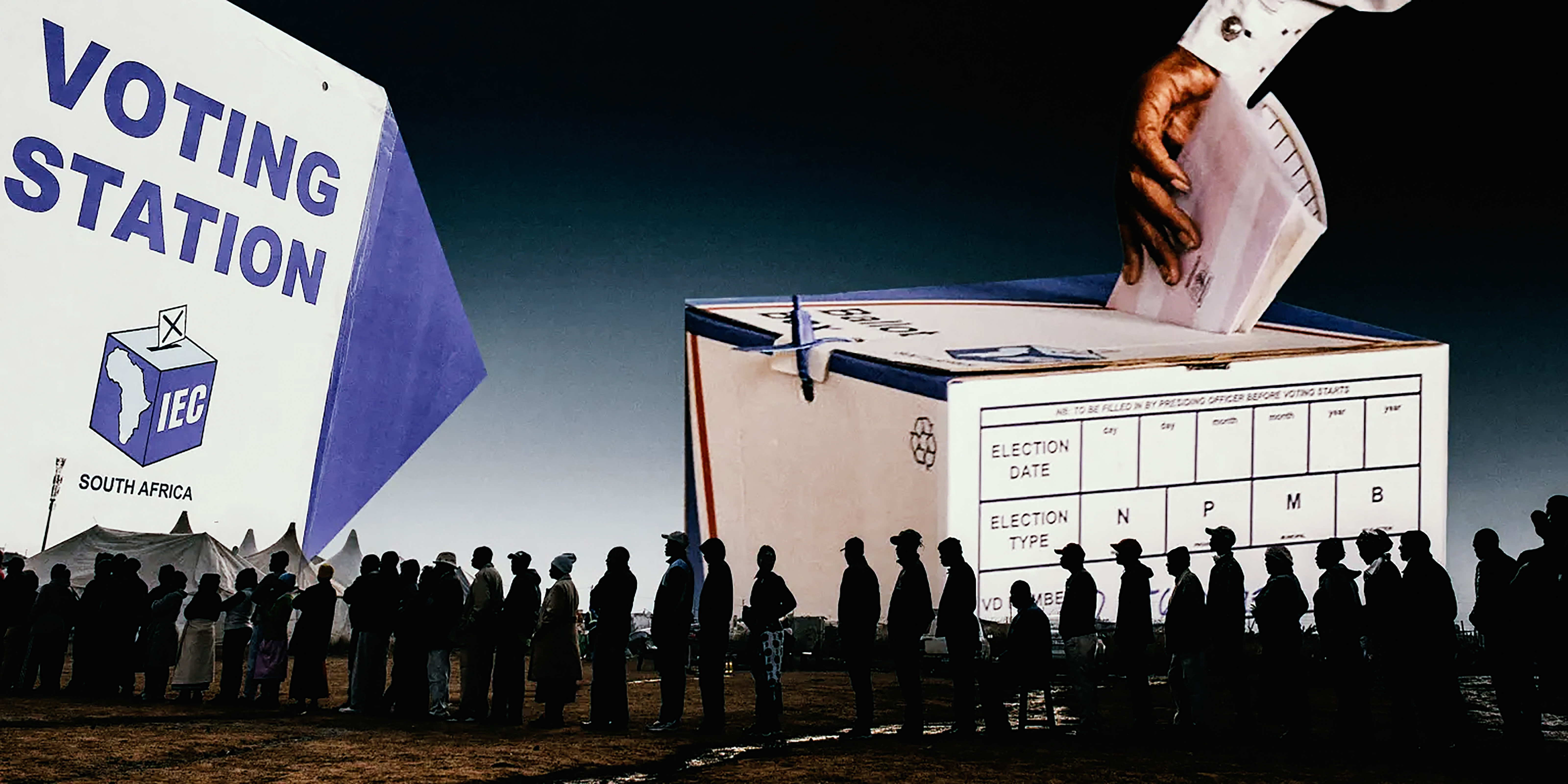

Such “profound distrust” in the national leaders, as the Barometer survey puts it – alongside flagging confidence in political parties – raises serious questions about South Africa’s constitutional democracy ahead of the 2024 elections.

Central factors in the plummeting trust levels were corruption and State Capture.

Almost three-quarters of South Africans, or 74%, say most politicians have no real will to fight corruption. Eight in 10 South Africans, or 82%, agreed that corrupt officials often get away with it.

This helps to explain dipping public trust in institutions critical to democracy – including political parties, national government, the presidency, Parliament and the Constitutional Court.

Most trusted in 2023 is the SABC (57%), followed by the South African Revenue Service at 46% trust levels, and the Constitutional Court at 38%, which is significantly lower than its top trust rating of 65% in 2011.

Parliament, at 33% trust in 2023, has lost almost half its trust levels that stood at 62% in 2007. The 2023 trust levels are a little better than the worst showing during the State Capture years of 31% trust in 2017.

Trust in national government has dropped to 32% in 2023, from a high in 2007 at 63%.

The president has tracked a little better, at 35% public trust.

Assessment of improvement over time has remained consistently low, even though eradicating inequality, for example, has been a priority for the democratic government since 1994, said IJR researcher Kate Lefko-Everett on Thursday

By 2007, only 22% believed inequality and the jobs situation had improved, alongside 32% for improved personal safety. In 2013, 30% believed inequality had improved, 31% for a better job situation, and 38% believed personal safety improved.

But this low assessment of improvement declined further in 2023 – just 17% thought inequality had gotten better; 25% thought jobs improved and 28% believed personal safety was better.

Such findings come in the wake of a Statistics SA survey that emphasised greater access to water, electricity and formal housing. The ANC has made much of these findings to underscore improvements during its time in government.

The SA Reconciliation Barometer, like previous surveys, indicates a different lived reality for ordinary South Africans.

Despite being described as the world’s most unequal country by, among others, the World Bank, South Africans appear determinedly glass-half-full – at least on some matters.

“South Africans are moderately optimistic that the future will bring continued improvements in relationships between people, including in areas such as reconciliation and respect for languages and cultures.

“Expectations of improvement are much lower, however, in key governance concerns such as inequality and corruption,” says the IJR public opinion survey.

That most South Africans shared a common view of apartheid as oppressive, undemocratic and a crime against humanity provided an important foundation to continue to deal with inequality, justice, reparations and restitution – regardless of how fractured the society and country are regarded currently.

Inequality, poverty, racism and corruption emerged as the biggest barriers to reconciliation.

But the SA Reconciliation Barometer’s finding of “a growing distrust in leadership, limited confidence in public institutions and widespread concern over corruption” must raise red flags for South Africa’s constitutional democracy – now and beyond the 2024 elections. DM

Maverick Citizen

IJR survey confirms plummeting confidence in public institutions and politicians