In 1987, Anthony Akerman had already been living in Amsterdam for 12 years and had taken Dutch citizenship. He decided to visit South Africa after his anti-war play “Somewhere on the Border” had been performed there, but was denied a visa.

So instead, he went to Italy to work on a new play. En route back to Amsterdam, he made a stopover near Zürich where his adoptive sister was living with her Swiss husband and two children. She received Fair Lady from South Africa every month and told him she’d read an article saying the Child Care Act of 1983 had been amended and adoptees were now able to access information relating to their biological parents – provided they had a letter of consent from their adoptive parents. As it was a sensitive issue, she asked him to write to their parents on her behalf.

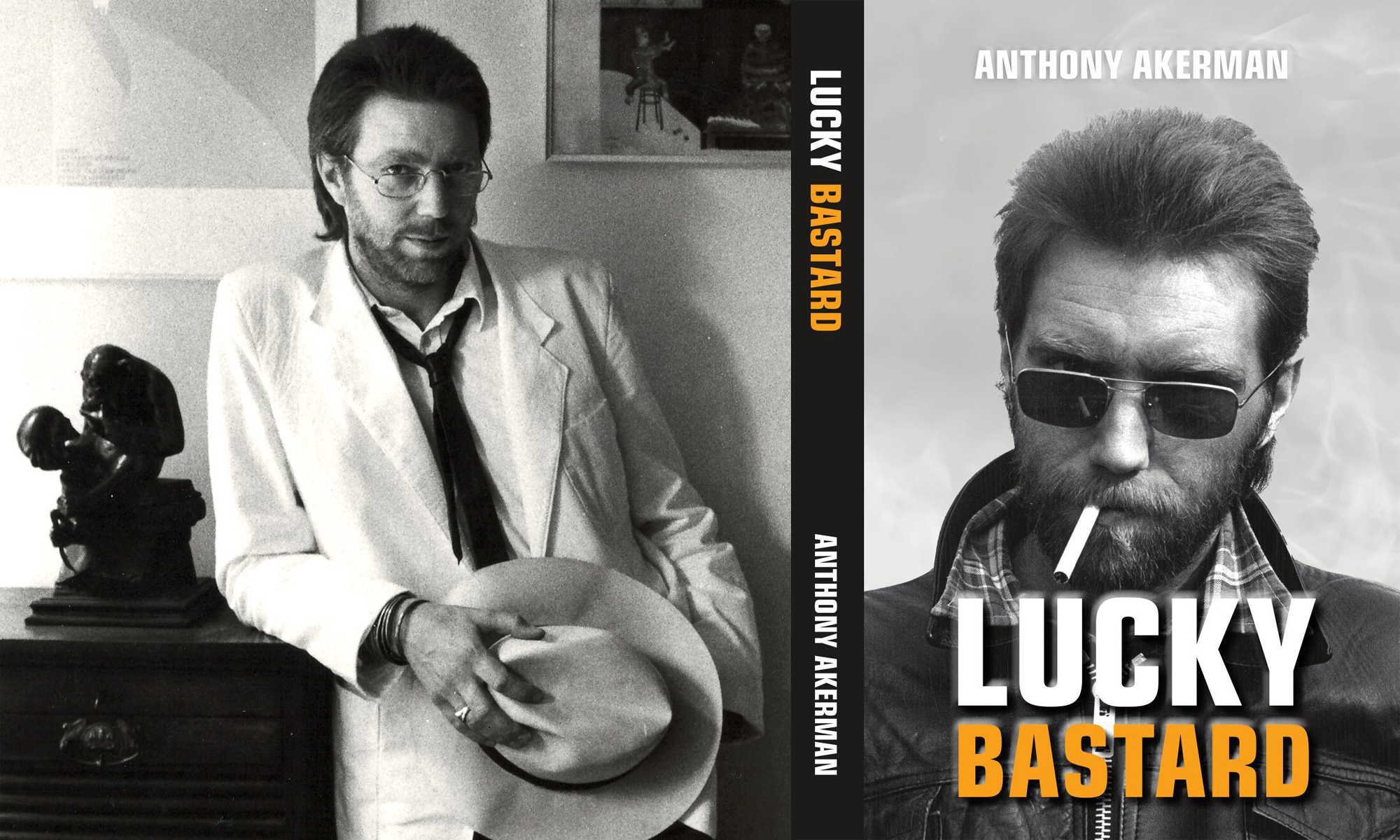

What follows is a lightly edited excerpt from Akerman’s memoir Lucky Bastard.

***

When Gill told me about the Fair Lady article, I thought I’d moved on from my adoption issues but, if it was important to her, I felt she had every right to whatever information she could get hold of. When I got back to Amsterdam, I wrote Mum and Dad a long letter. I discussed our adoption, told them Gill wanted a letter giving her permission to initiate a trace and explained that they shouldn’t think of it as rejection.

Then, almost as an afterthought, I asked Dad if there was anything else he knew about me. If there was, I wrote, please don’t take the secret to your grave. I meant that quite literally. Dad was turning seventy and, at the time, I thought that was ancient. I posted the letter, let Gill know I’d done so and then forgot about it.

In Amsterdam, post was delivered around mid-morning. If I was home and heard the postman, I’d go down the spiral staircase, pick up the letters off the flagstones in front of the street door and go around the corner to Ijssalon Tofani for a macchiato. Not many people outside Italy were familiar with macchiato in the 1980s, but Tante Truus had married a Mr Tofani from Luca.

Read in Daily Maverick: Anthony Akerman’s memoir – ‘Lucky Bastard’

On the morning of Tuesday, 1 September 1987, I sorted through my post while Truus attended to my order. There was an aerogramme from Dad. I slit it open and saw it was a reply to the letter I’d written on 21 July. He began by explaining that such information as he had, had come from papers he’d had to sign at the Child Welfare Society. He had my attention. He went on to explain that the policy had been to tell adoptive parents as little as possible to minimise the risk of any future embarrassment to the birth mother. He said they’d waited about a year before receiving a phone call to say a baby had been found for them.

“You were born at the Mothers’ Hospital, Durban. We fetched you as soon as we were allowed to, within a couple of weeks of your birth. All I could glean from documents I signed at the time was that your mother was probably a nurse. Your name at birth was Peter Farnham, so your mother was a Farnham. We were not allowed to see your mother. We know no other details.”

Peter Farnham?

I was amazed Dad had remembered. I was sure he hadn’t kept any papers because, as a child, Gill had jimmied his rolltop desk and cupboards looking for clues and came up empty-handed. But in retrospect that seems unlikely. Surely, he’d have kept some paperwork to prove, if necessary, that they were my legal parents. But where? If he’d died before he’d written that letter, I might never have known I’d been named Peter Farnham.

In all my fantasising about my adoption, it never occurred to me that I must once have had a different name. And yet it’s so obvious. A child must be registered within three weeks of birth, and to register a child you need a name.

I’d had to wait thirty-eight years to find out I was Peter Farnham. But was that who I was? When I got back to my flat, I stared in the mirror. Was that Peter Farnham looking back at me? Anthony Akerman or Peter Farnham? Why had I been called Peter? Did I look like a Peter? No, I didn’t look remotely like any of the Peters I knew. But maybe I’d have looked like a Peter if I’d always been called Peter. People do start to look like their names, don’t they? And if they feel they don’t, they change them. I was sure I didn’t look like my nickname Tony and reverted to my given name. If Mum and Dad had known my name was Peter, why did they change it? Well, I already had an older cousin called Peter Akerman and I suppose it would have seemed distinctly unimaginative to have given the next boy in the family the same name.

Now I knew her surname

So when Dad told me he thought my mother had been a nurse, he wasn’t just stringing me a line. And now I knew her surname or, if she was married, at least I knew her maiden name. I couldn’t think of anybody I knew with that surname, but Farnham sounded familiar. What did the name tell me? There was a town in England called Farnham, but it didn’t necessarily follow that she was from England or was even English-speaking. But she had stepped out of the world of myth and had become fact. I recorded the following in my journal:

“If she’s still alive I wonder if she ever wonders what happened to the child she called Peter. She must have given me that name. I also know now – for sure – that I was born out of wedlock. Am I going to want to trace her? It does interest me. Yes, it does.”

After Dad wrote to Gill she called and told me what her name had been at birth. Finding out the name she’d been given also came as a shock to her. It took Dad a few more weeks to write the letter addressed to the Registrar of Adoptions in which he gave his consent for her to trace the names of her natural parents, and not long after that I received a call from Gill.

As soon as she’d been told her original name, she wrote to the Adoption Centre. A Mrs Jordaan referred her to the Registrar of Adoptions, told her the legal position had changed and that, if she was over twenty-one, she no longer required the consent of her adoptive parents to obtain identifying information about her biological parents. By the time Mrs Jordaan replied, she’d already written to the Registrar of Adoptions, enclosed Dad’s consent letter and asked for whatever information they could give her.

A Mrs Honiball replied telling her that inquiries had been made and the information received had been forwarded to the Child Welfare Society in Cape Town. Gill received another letter from Mrs Jordaan. She gave Gill her mother’s first name and confirmed her married name. Mrs Jordaan had called the number in the phone book and spoken to one of her daughters – Gill’s biological half-sister – pretending to have been a nursing sister with her mother and saying she wanted to re-establish contact. Gill’s sister said her mother had died the previous year.

Nothing more she could do

Mrs Jordaan offered her condolences and told Gill there was nothing more she could do, because Gill’s mother may never have told anyone she’d given up a child for adoption. Gill was distraught. She promised to send me copies of her correspondence with the Adoption Centre and made me promise not to write to them until she’d received answers to all her questions. She didn’t want the Adoption Centre – like everyone else – to prioritise my interests over hers.

Although Gill felt cheated that she’d never meet her mother, she at least had some identifying information. She knew her mother’s name, what her occupation had been, where she’d lived, her husband’s surname and that she had, at least, two biological sisters. I knew nothing, except that my name had been Peter, my biological mother’s surname was Farnham and that it was likely that – like Gill’s mother – she’d been a nurse. Gill phoned a week later, told me her husband Hans had called all the people in that suburb with her mother’s married name and had now pinpointed the family. She was going to write to the Adoption Centre to ask how she should proceed.

Gill’s experience gave me a sense of urgency. I persuaded her to give me the address and wrote to Mrs Jordaan on 17 December. I gave her my birth name, date of birth and a shopping list of questions: what was my mother’s full name, where had she been born and where did she grow up, who were her parents, what was her occupation, how old was she when I was born, did she ever get married and have a family, was she still alive and, if so, did she live in South Africa?

But maybe none of these questions would ever be answered. Like Gill’s mother, she may have died. She may have left the country and been untraceable. There was also the possibility that she’d refuse to have contact with me.

But if she was still alive, I was determined to contact her because she was the only person who’d know my origin story. For thirty-eight years I’d thought it’d be impossible for me ever to find out where I came from. I’d learnt to live with it. Now that it seemed possible, I became impatient. When would I get a reply from Mrs Jordaan?

My letter would have arrived just before Christmas and Christmas was the summer holiday. People went to the beach, offices closed and I imagined my letter gathering dust in the hallway under the letterbox in the door of the Adoption Centre. Then, on 22 January, I received a letter from Mrs Jordaan. She told me my birth mother’s name was Vera Geraldine Farnham and that she’d lived in Cape Town before I was born. If she was able to trace her, she asked, did I want to make contact with her?

Glaringly obvious

I’d forgotten to state the glaringly obvious.

I phoned Gill a few days later and gave her an update. She told me she’d had a phone call from Dad who asked if she’d been able to find out anything more about her mother. She said she didn’t say anything because she thought it might have hurt them. But she said Dad had said it was all out in the open now and they were very interested. I decided to write to them once I knew more.

By 2 March I’d still heard nothing and so I called the Adoption Centre. I spoke to Mrs Bruce, a social worker, who said Mrs Jordaan only worked mornings. Mrs Bruce said these matters were extremely sensitive and they had to proceed with caution. She assured me I’d be informed as soon as they knew anything. But the next morning, I called Mrs Jordaan. She said it could take months. They couldn’t access records kept in terms of the Population Registration Act – which could give them the information within minutes – so they had to do a lot of painstaking research and detective work. I just had to be patient. At least I knew my mother’s first names.

Vera Geraldine Farnham.

Then I remembered Dad saying my Uncle Halley had vetted me before I was adopted, so I wrote and asked him what that had entailed.

Uncle Halley and Auntie Joyce with family, circa 1949. (Image: Anthony Akerman)

Uncle Halley and Auntie Joyce with family, circa 1949. (Image: Anthony Akerman)

“Joyce and I have given much thought to your letter of 2 April and, as her recollections of the adoption are still reasonably clear, I have asked her to reply to you. What records I have retained from my Durban medical practice, including my 1949 diary, make no reference to the adoption. This is as I would expect as very strict secrecy was kept in such matters. Until yesterday, neither of your parents were aware of Joyce’s participation, for instance. Apart from what Joyce has told you I have nothing further to add except to confirm that your mother was a fine person in every sense of the word.”

I then opened Joyce’s letter.

“Your letter to Halley has brought back into my mind very vividly a visit I paid in the company of Miss Mabel Bayley, who was a very old friend of my family’s and was Diana’s godmother. She had, through her influence with members of Child Welfare and the Adoption Society, and through her tender concern for John & Paddy, found an ‘eminently suitable’ baby. She took me with her to see you and your young mother. As this was all very confidential, I have never spoken of it to your adoptive parents or anyone else – thus John & Paddy did not know of my meeting your mother and of seeing you before they did.

Miss Mabel Bayley. (Image: Anthony Akerman)

Miss Mabel Bayley. (Image: Anthony Akerman)

“I remember her clearly – young, with very fair delicate skin & straight blonde hair, petite and with the most pleasing presence and composure. She had chosen to spend 3 months in the home for unmarried mothers so that she could breast feed her babe for the first vital three months of his life, thus giving him the optimum start. I respected her greatly for this as it is very hard to surrender a baby after 3 months & far more traumatic than at, the usual for adoption, two weeks.

“She was a nurse; I think still doing her training. Your biological father was a student. Thus you’ll realise both were potential ‘professionals’ and from good families. They were young & unable to marry and support a child. It was certainly not due to selfishness or lack of love that your mother parted with you. (I know nothing of your ‘father’s’ deliberations in all this.)”

This was the first glimpse I’d been given of my birth mother. Auntie Joyce had seen her, been in the same room with her, so now I could dispense with many of the mythological constructs of my youth. She hadn’t been killed in a car at a level crossing. She hadn’t been a Point Road prostitute. Both she and my unnamed father were young and unable to marry.

What caught me most off guard was that I’d spent the first three months of my life with her in an unmarried mothers’ home. In most other scenarios I’d invented, we’d been separated at birth. It had never occurred to me that she’d spent any time with me – let alone three months – before giving me up. And I was adopted by Mum and Dad because a former headmistress of Roedean Junior School called Miss Mabel Bayley considered me an “eminently suitable” baby.

Then on 19 April, a date that marked sixteen years since I’d arrived in Europe, I received a letter from Mrs Anne Bruce.

Delighted

“We are delighted to be able to tell you that we were able to establish your mother’s present whereabouts and were delighted to find that she lives in Cape Town. I personally called on your birth mother and found her to be a most attractive, warm, refined and intelligent person. She was understandably taken aback and moved to tears when I explained the reason for my visit. You have always been in her thoughts and she has very deep feelings for you.”

In the space of just two days, letters from Joyce Stott and Mrs Bruce had given me so many clues about my genesis. I cried as I re-read them and re-reading them now is still an emotional experience. Mrs Bruce continued:

“I told her a little bit about you and she was most delighted and would very much welcome letters and photos and will then personally answer all your questions. Should you wish to meet at a later stage she would be agreeable.” DM

Lucky Bastard is now available at Exclusive Books and most leading bookstores, also on Takealot, Amazon and Kindle. Reviewers are asked to direct all enquiries to ikesbooks@iafrica.com

Anthony Akerman will be discussing Lucky Bastard at the Midlands Literary Festival on 31 August 2024, shortly after the Durban launch at Ike’s on 28 August 2024.

Miss Mabel Bayley. Image: Anthony Akerman

Miss Mabel Bayley. Image: Anthony Akerman