President Cyril Ramaphosa’s recent visit to Washington, DC, has offered a platform for resetting relations and exposed deep fissures in bilateral relations.

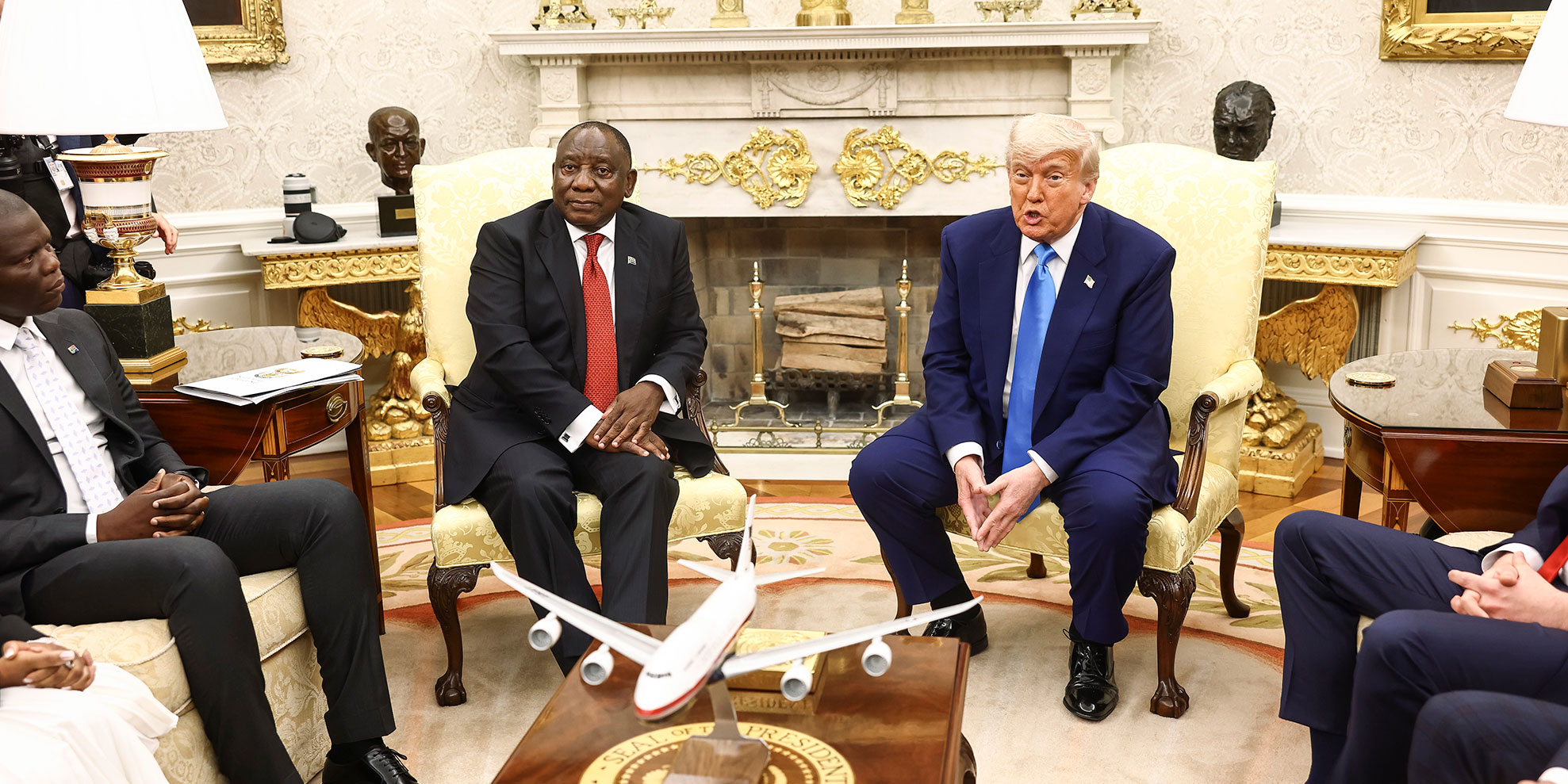

The challenges of navigating a world increasingly shaped by ideological polarisation and performative politics were laid bare in the livestreamed meeting between Ramaphosa and his entourage and President Donald Trump and his staff.

The meeting was anything but routine – while not descending to the level of chaos that characterised the Trump-Zelensky meeting, the American president did confront (read: ambush) Ramaphosa on claims of white genocide.

A video featuring Julius Malema’s trademark inflammatory rhetoric and a row of white crosses was presented as evidence of state-sanctioned violence against white farmers. Ramaphosa remained composed (looking bemused, even) and rebutted these claims, emphasising South Africa’s commitment to multiparty democracy and clarifying that EFF and MK sentiment reflected a minority view and did not reflect government policy.

While observers have offered a mixed interpretation, mine is that the meeting went as well as could be expected, given how acerbic American criticism of South Africa has been in the context of increasingly tense relations.

The South African delegation’s decision to maintain calm, even in the face of provocation, appears a strategic tactic to de-escalate tensions and reset the relationship on a firmer footing – leading with an honest assessment of the on-the-ground realities (albeit with unnecessarily graphic descriptions of crime from some in the delegation) and using a not-too-assertive approach.

The logic, it seems, was to use the visit as a platform to correct misperceptions and begin a reset, without provoking further rupture.

Beneath a difficult relationship

While the meeting has been closely watched, the underlying deterioration in the relationship is far more complex. These are two actors with fundamentally divergent worldviews amid a failure to find common understanding at a time when a global realignment appears to be under way.

On one side is a resurgent US under a Trump-led foreign policy that is transactional, nationalist and deeply sceptical of multilateralism. Trump’s White House has embraced a worldview framed around selective alliances based on loyalty rather than shared values.

In this context, South Africa’s non-alignment – a cornerstone of its post-apartheid foreign policy – has been recast in Washington as defiance, or worse, outright hostility.

Pretoria, for its part, sees itself as part of a multipolar future in which there is a more equitable seat at the table for those in the Global South. South Africa’s BRICS membership, deepening ties with China and Russia, and outspoken criticism of Western dominance in global institutions are not anomalies, but features of a strategy that sees the Global South as no longer beholden to the geopolitical logic of the Cold War or unipolar American power.

Ramaphosa’s government has made clear that his administration’s foreign policy is driven by constitutional principles, historic solidarity with anti-colonial struggles, and a desire for global equity. Washington, however, views these positions through a much narrower and increasingly ideological lens.

Ramaphosa’s visit was intended to highlight the country’s diversity, being honest about its challenges, but reaffirming a commitment to inclusive governance, while perhaps also trying to re-explain South Africa’s foreign policy outlook. He went there with a conciliatory tone, an appreciation of American contributions to the global order, and a desire to boost trade and investment, clothed as a request for help.

Solid foundation for cooperation

There is a solid foundation for continuing economic and political cooperation. The US is an important trading partner for South Africa, with 600 US companies active in the country, while several South African firms also invest heavily in the US.

Indeed, South Africa offers a range of opportunities for US economic engagement across multiple sectors, including renewables, mineral resources, ICT, infrastructure development and agriculture.

Furthermore, both nations share interests in regional stability. South Africa plays a crucial role in peacekeeping and conflict mediation efforts on the continent, particularly in southern Africa and the Great Lakes region. The US has faced a changing landscape of global influence in Africa, and partnering with Pretoria can offer it a different platform for engagement.

But even shared interests have proven vulnerable to distortion in the current climate, risking being drowned out by mutual mistrust, symbolic politics and domestic pressures.

While not a diplomatic breakthrough, the media spectacle of Ramaphosa’s visit exposed how deeply domestic political imperatives now shape bilateral engagement. If it serves any form of substantive turning point, it is in making clear that a recalibration will require deeper diplomacy (including public diplomacy) as well as political will behind the scenes.

For South Africa, the key question is whether it can pursue a principled foreign policy while maintaining strategic relationships with major powers. For the US, the challenge is to recognise that non-alignment is not hostility, and that partnership is most successful when built on mutual respect, not coercion.

Essential steps

Looking ahead, a few steps are essential if this relationship is to be salvaged.

First, there needs to be a revival of diplomatic dialogue beyond theatrical moments. Both countries have long-standing mechanisms for bilateral engagement that should be reactivated at a senior level, with clear channels for addressing areas of tension. To this end, South Africa needs diplomatic representation that can cut past the rhetoric and get through to important figures in the Trump administration.

Second, both sides must invest in the Track II relationships that have traditionally undergirded diplomacy – business partnerships, academic exchange and civil society dialogue. These are often more resilient than government-to-government relations and can provide ballast in turbulent times.

Finally, there must be a recognition that the world is changing. South Africa is no longer simply a beneficiary of US aid or a passive participant in Western-led initiatives.

It is a regional power with assertive diplomatic positioning and, despite having constrained and uneven power, an important voice on the international stage. That voice will not always echo Washington’s, but if treated with respect, it can still be an ally.

Indeed, diplomatic equilibrium does not necessarily require identical interpretations of the world, but it does require strategic maturity.

Ramaphosa’s visit did not mend fences, but it did force both sides to confront the new reality of their relationship. Whether this signals rupture or renewal remains to be seen.

But one thing is clear: the work of diplomacy must now begin in earnest, far from the cameras and the media, and rooted in the hard, often uncomfortable, business of listening.

Ramaphosa’s visit underscores the importance of sustained, high-level diplomatic engagement. It is a reminder that diplomacy, though often tested, remains essential in bridging divides and fostering understanding in an increasingly fragmented world. DM