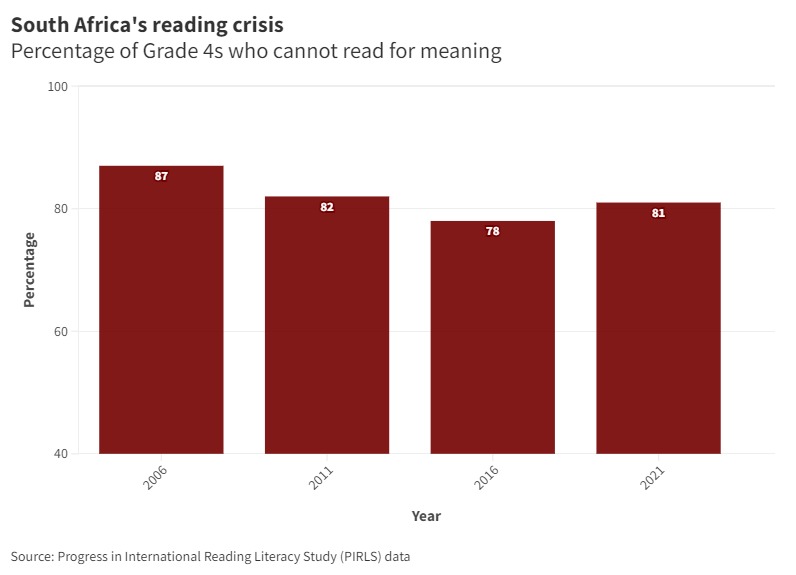

Children’s reading levels in South Africa have been in dire straits for some time, but the release of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) 2021 results shows that for the current cohort of learners, vital ground has been lost.

In 2021, 81% of Grade 4 learners were unable to read for meaning in any of South Africa’s 11 official languages, according to PIRLS data released by the Department of Basic Education on Tuesday. Previous iterations of the study in 2016 and 2011 put the percentage of Grade 4s who couldn’t read for meaning at 78% and 82%, respectively, suggesting that recent learning losses have set reading outcomes back a decade.

The PIRLS 2021 study took place at a time of ongoing learning disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Shutdowns, delayed school openings and rotational timetables led to reduced class time, with a recent research note, Covid-19 and the South African curriculum policy response, estimating that most learners received only a third to half of the instructional time that they would have in a normal year throughout 2020 and 2021.

“We had a serious crisis in early grade reading before the pandemic and clearly, the pandemic has exacerbated the crisis. [However], it’s not as though the crisis… is attributed just to the Covid-19 pandemic — there’s a long-term problem that South Africa faced, and it continues to face, [in] the challenge of early grade reading,” said Professor Brahm Fleisch of the School of Education at the University of the Witwatersrand.

South Africa exhibited the largest decline in reading outcomes of all 33 countries with PIRLS data in 2016 and 2021. Education experts have sounded the alarm that despite this, there remains no coherent national plan or budget to address learning losses.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Still no national plan to address SA’s reading crisis as percentage of children who can read for meaning declines

A generation of learning losses

Before the pandemic, South Africa was on a trajectory of improvement when it came to children’s literacy levels. PIRLS data shows that the number of Grade 4s who could read for meaning went from 13% in 2006 to 22% in 2016.

The PIRLS 2021 findings do not necessarily mean the infrastructure behind this trajectory has regressed. Many of the elements that led to improvements in South Africa’s education system in the past decade — such as a stable curriculum, national distribution of workbooks and the National School Nutrition Programme — are still in place, according to Nic Spaull, an associate professor of economics at Stellenbosch University.

“Let’s say a child went into Grade 1 in South Africa next year, in 2024. That child would likely experience an education system that’s quite similar to the pre-Covid education system,” he said.

“But for all the kids that are currently in the system, particularly the ones that were in primary school [during the pandemic], their learning losses will endure. It’s not like tomorrow they’re going to just catch up on a year that they lost.”

Without interventions to bridge the learning losses, these children run the risk of being perpetually behind and in catch-up mode when it comes to reading and other skills. Fleisch noted that while the pandemic had an impact on literacy levels, it was not a universal impact. Some countries that participated in the PIRLS 2021 saw minimal change in reading outcomes, such as the United Kingdom.

In South Africa, English and Afrikaans schools did not experience a decline in reading levels between 2016 and 2021, while most African language schools did see a decline.

“It’s not that South Africa overall is declining, [rather] the decline seems to be concentrated particularly in the poor schools, where historically [they] would have done the test in one of the nine African languages,” said Fleisch. “So, Covid-19 wasn’t universally impactful. It seems to have adversely affected the poorest [communities].”

The four provinces that exhibited the greatest decline in reading outcomes were North West, Free State, Mpumalanga and Limpopo. The three provinces with the smallest declines were the Western Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape.

Incoherent national policy

Some education experts have criticised the government for an inadequate, underfunded and uncoordinated approach to addressing learning losses in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“If you look at some of the other countries, they’re announcing huge investments and things like after-school tutoring, Saturday classes, holiday classes, home tutoring,” said Spaull. “We’re going back to ‘business as usual’, whereas we needed a big boost.”

No money was allocated for plans to catch up on the lost time and learning in the Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement and the Department of Basic Education’s budget from 2020 to 2023, according to Covid-19 and the South African curriculum policy response.

However, it stated that in May 2023 — shortly before the release of the PIRLS 2021 results — the Western Cape launched a costed and budgeted plan for a catch-up campaign, “#BackOnTrack”. This allocated R1.2-billion for activities such as tutoring, Saturday classes and holiday camps for grades 4 to 12. A further R118-million was allocated to grades R to 3.

In the same month, the directorate of Teacher Development under the Department of Basic Education released Learning Recovery Programme (LRP) guidelines, aimed at assisting teachers in identifying and planning around the need to catch up on lost learning. No budget, time or material resources have yet been allocated for the catch-up programme at the national level, according to the report.

To address learning losses, the national and provincial education departments need to find extra time within learning systems, according to Professor Ursula Hoadley of the School of Education at the University of Cape Town. This can involve extending instructional time, prioritising engagement with key subjects — such as literacy and mathematics — or accelerating programmes.

“I also don’t think that this can be done without a budget. You need particular materials… and you need to pay people to help with remediation,” said Hoadley.

Speaking at the launch of the PIRLS 2021 results on Tuesday, Minister of Basic Education Angie Motshekga said enhancing learners’ ability to read for meaning was a top priority, and highlighted the success of initiatives such as the Primary School Reading Improvement Programme.

“We’re finalising our revised national reading plan to address the gaps in our approach… Our plan will ensure further provision of a minimum learning and teaching support material package, especially designed to support reading,” she said.

“Our primary objective is to ensure that every learner has access to high-standards education that caters for their needs, regardless of their socioeconomic background, and as a sector we remain steadfast in fulfilling this critical mandate.” DM/MC