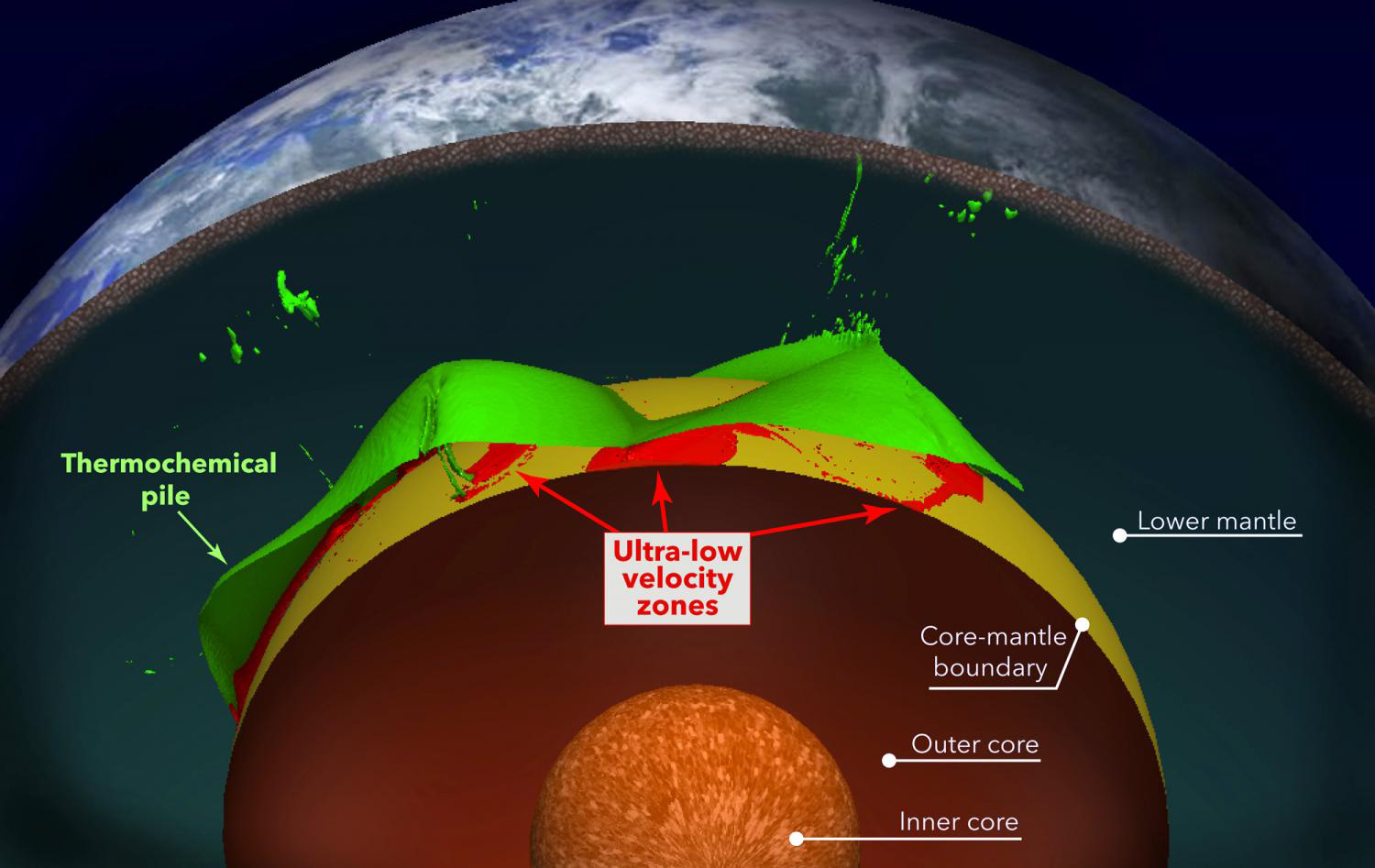

There are vast areas of… something… surrounding the earth’s core. Geologists call them large low-shear velocity provinces or superplumes. They’re massive, representing around 8% of the volume of the mantle or 6% of the entire Earth, and nobody knows for sure what they are, or what they’re made of.

But there are theories. One is that they’re the left-over mantle of a protoplanet that smacked into the earth billions of years ago, remelting everything and throwing huge amounts of material into space, which eventually coalesced to be the Moon.

Another theory is that ancient continents collided as they floated over our planet’s liquid mantle, one squeezing part of the other down towards a continental “graveyard”.

The superplume under Africa is about the size of the continent and about 1,000 kilometres thick; the other beneath the Pacific Ocean is about the same size but shallower. They’ve only fairly recently been discovered using seismic tomography of deep Earth by Arizona State University scientists Dr Quain Yuan and Dr Mingming Li.

Big splat

The most interesting theory of the existence of the blobs concerns a Mars-sized planet called Theia, which is thought to have collided with the Earth during the last stages of planetary formation. Yuan and Li postulate that in such a collision, Theia’s core would merge with Earth’s after the impact. The intruder would wind up mostly destroyed, with pieces flung into space to create the Moon.

Theia slams into Earth, an artist's impression. (Image: Universe Today)

Theia slams into Earth, an artist's impression. (Image: Universe Today)

Theia's impact on Earth. (Image: Dr Mingming Li)

Theia's impact on Earth. (Image: Dr Mingming Li)

Rendition of seismic tomography results beneath Africa. (Image: Mingming Li_ASU)

Rendition of seismic tomography results beneath Africa. (Image: Mingming Li_ASU)

A map of the superplumes. (Image: Dr Mingming Li)

A map of the superplumes. (Image: Dr Mingming Li)

If its mantle was denser than that of Earth, maybe richer in iron, it would not merge but work its way towards the core, forming the two superplume blobs.

This movement would be possible because Earth’s mantle is made of hot rock that behaves more like fudge simmering slowly on a stove. Its heat comes from both radioactivity within the mantle rock and from the planet’s core, the centre of which is about as hot as the Sun’s surface. Mantle rock responds to this heat with a slow churning motion.

Slow grind

The other theory has to do with the movement of tectonic plates that float the continents like rafts of pond weed on a wind-blown lake.

“You can have various mechanisms, such as plate tectonics, that push rock of differing chemistries into the deepest mantle anywhere on Earth,” says Arizona State University seismologist Professor Edward Garnero. “But once these different rocks have gone down deep, convection wins and sweeps them to the hot regions, namely, where the continental-sized thermochemical piles reside.”

Magnetic flip

It’s been speculated that the superplumes may be the birthplace of past and future magnetic pole reversals. Based on studies of old volcanic basalt, scientists know that the magnetic field of our planet has flipped many times throughout the planet’s history.

Since 1840 its strength has decreased 16%, with most of the decay related to the weakening field in the South Atlantic Anomaly — leading to much speculation that the planet is in the early stages of a field reversal.

“It has long been thought that reversals start at random locations, but our study suggests this may not be the case,” said Dr John Tarduno from the University of Rochester, NY, first author of a paper published in the journal Nature Communications. “We suggest that a statistically larger number of reversed polarity fluxes might occur along the sharp and steep African large low-shear velocity provinces boundaries.”

The scientists hypothesise that the superplumes affect the direction of the churning liquid iron that generates Earth’s magnetic field.

“The shift in the flow of liquid iron causes irregularities in the magnetic field,” says Tarduno, “ultimately resulting in a loss of magnetic intensity, giving the region its characteristically low magnetic field strength.”

At a certain point the polarity might flip. The consequences to Earth’s inhabitants are unknown, but could be considerable.

With the blobs too deep for us ever to test, a definite answer about their origin may elude us forever. But if the Earth’s polarity flips, we’ll certainly know about it. For a start, our compasses will read back to front. We would be exposed to high levels of solar radiation and our satellites would probably go haywire. DM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REeWvTRUpMk

Map of superplumes.(Photo: Dr Mingming Li)

Map of superplumes.(Photo: Dr Mingming Li)