The Skeleton Coast in Namibia is the breeding ground for a really spectacular nightmare. Beneath the sea it’s burgeoning with life, but on land it’s best described by utter absences.

There’s no soil, virtually no life, no mountains, no escape from sun-blackened expanses of flat gravel and sand. And, when the wind’s blowing (as it generally does), no relief from being sandblasted the moment you step out of your vehicle.

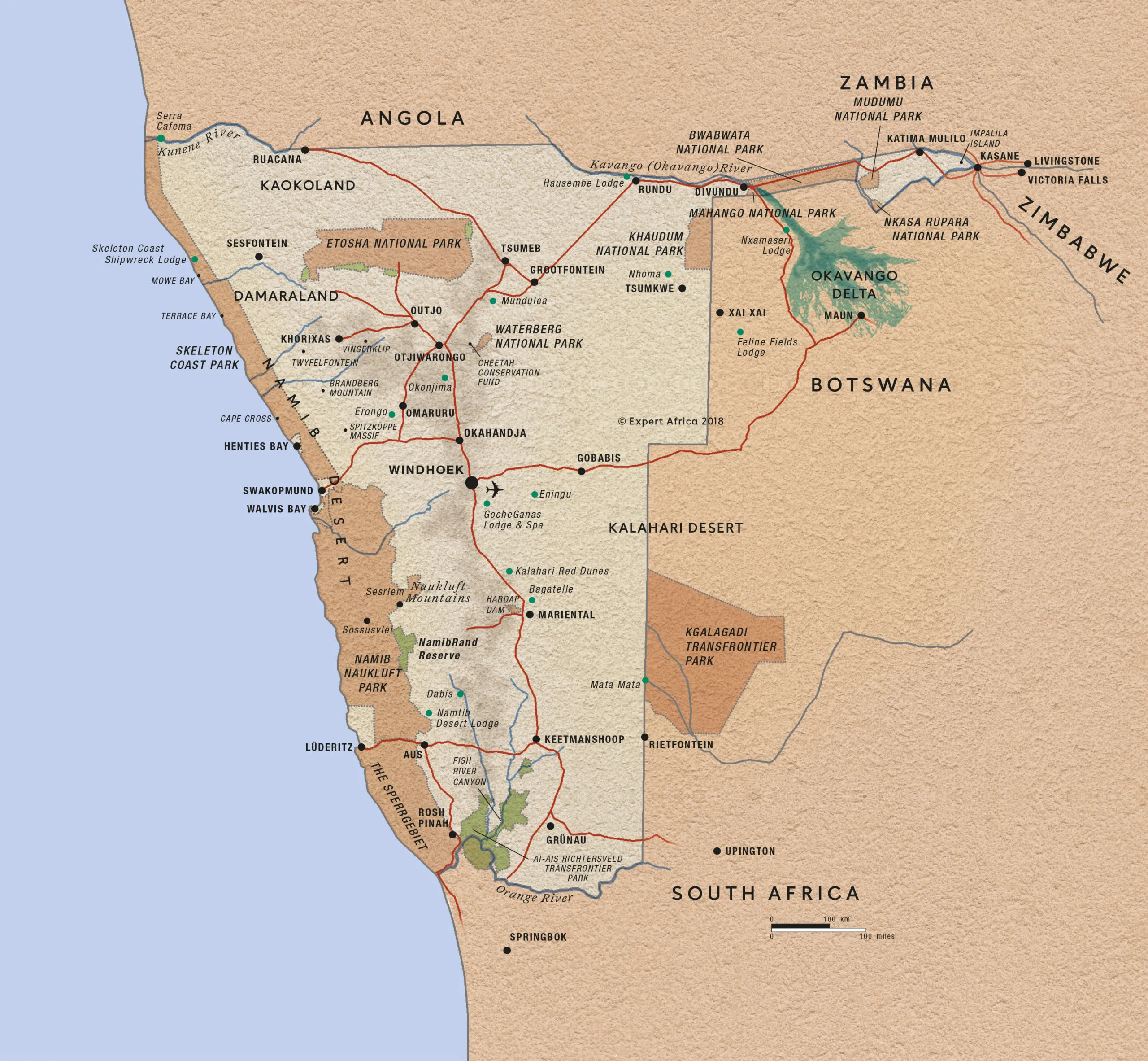

Map of Namibia (Supplied)

Map of Namibia (Supplied)

But the scale of “the nothing” is thrilling. Our Land Cruiser, just then being de-painted by flying grit, felt like a space buggy bounding across another planet. It was a privileged glimpse of what the world will look like at the end of time.

The journey to this extremely weird piece of African coast began in Kamanjab on an unexpected public holiday. We were low on supplies after wandering around western Etosha and the only thing open was the garage and a quirky forecourt shop.

The sign on the takeaway stoep offered some dubious advice: “Due to economic cutbacks, the light at the end of the tunnel has been turned off.” On a pillar was: “Today’s menu: eat it or starve.” Fuse tea and Afri-water (whatever they were) were on offer. A friendly local offered to sell us some gemsbok boerewors and Gordon’s gin. We bought them thankfully and pressed on westwards.

Kamanjab store for fuse tea and gin. Image: Don Pinnock

Kamanjab store for fuse tea and gin. Image: Don Pinnock

Kamanjab store sign. Image: Don Pinnock

Kamanjab store sign. Image: Don Pinnock

Kamanjab store sign. Image: Don Pinnock

Kamanjab store sign. Image: Don Pinnock

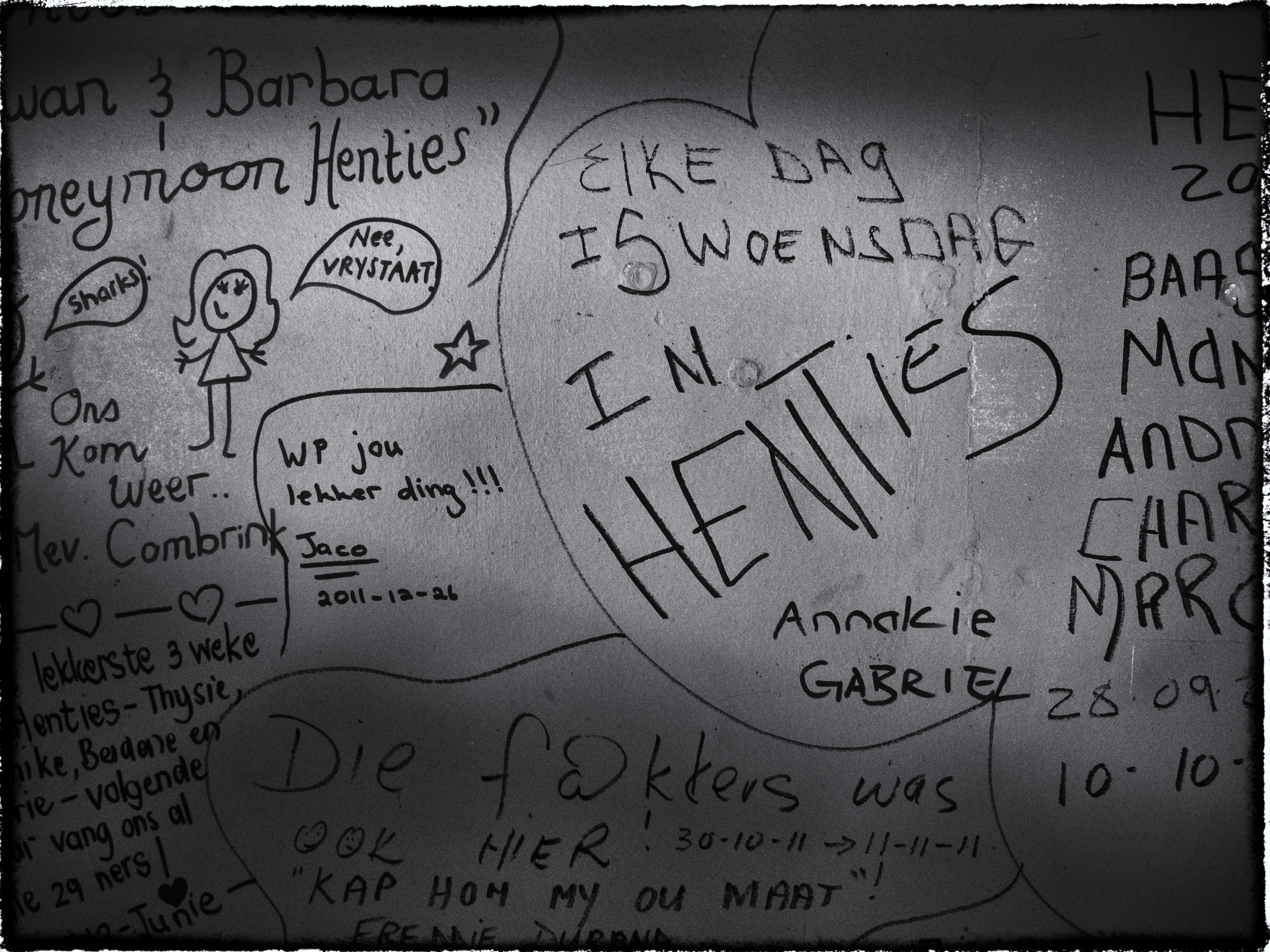

Graffiti in a Henties Bay. Image: Don Pinnock

Graffiti in a Henties Bay. Image: Don Pinnock

For a while the scenery could be described as fairly normal, with rippling hills and Karoo-like vegetation. Over the Grootberg Pass things got odder. The steep road down the other side, with no obvious nourishing vegetation or water, was dotted with fresh desert-elephant boluses.

We switched back from steep rises to dry stream beds that would probably flash flood if it ever rained. The low trees gave way to tough bushes, which morphed to vast stony plains. These offered an occasional welwitschia which looked and probably was 1,000 years old. The Skeleton Park offices eventually appeared as a blip on a table-flat horizon. After that it was empty plains of stone and sand, sea-flat in every direction.

A T-junction offered two options: north to Torra Bay (permits required) and south to Henties Bay. We turned south into a mighty headwind. Just then the sharp, flinty road claimed a victim: a flat back tyre. When we raised the van on a high-lift jack, the wind blew it off sideways and the tyres simply slid over the gravelly surface.

The solution was, dare I say, ingenious. We boxed the tail of the stricken van between the bull-bars of two other vehicles, jacked it up and changed the wheel.

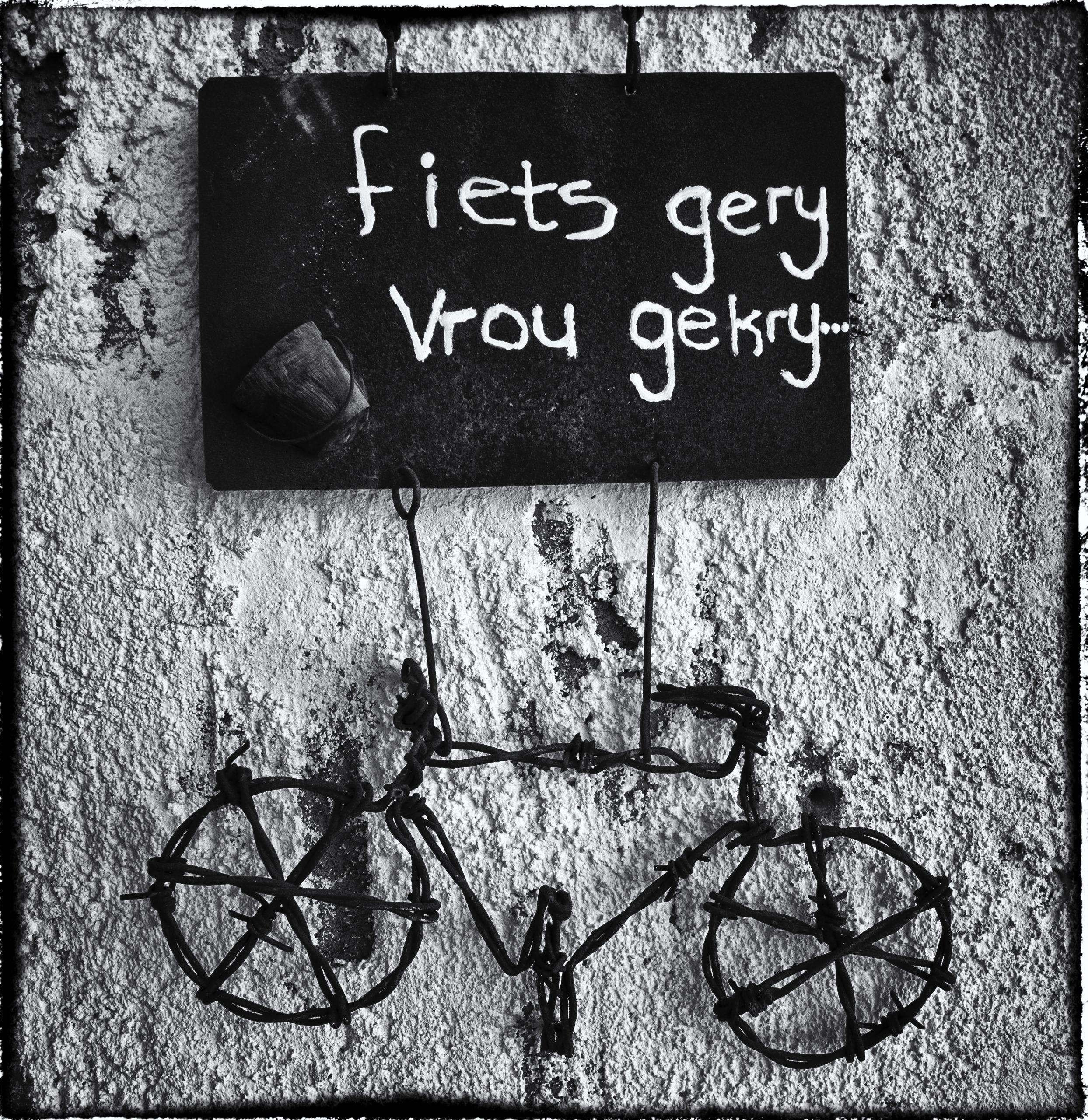

Kamanjab garage humour. Image: Don Pinnock

Kamanjab garage humour. Image: Don Pinnock

Fixing a flat in a screaming gale took two extra vans. Image: Don Pinnock

Fixing a flat in a screaming gale took two extra vans. Image: Don Pinnock

Tearing up this coast, the Benguela Current trade winds batter the shoreline day and night. The Bushmen called the area The Land God Made in Anger. Portuguese mariners simply referred to it as The Gates of Hell. The name Skeleton Coast was coined by John Henry Marsh as the title for a book he wrote in 1944 chronicling the shipwreck of the Dunedin Star – and it stuck.

There’s no shortage of skeletons: whales, ocean liners, trawlers, galleons, clippers, gunboats, rusting diamond mines and defleshed humans – testament to the perfidious current, heat and unrelenting winds. Wrecked onto this coast, the relief of having survived would soon have been replaced by the horror of where you’d landed.

There's no shortage of skeletons on the Skeleton Coast. Image: Don Pinnock

There's no shortage of skeletons on the Skeleton Coast. Image: Don Pinnock

The only road in the Land of Nothing. Image: Don Pinnock

The only road in the Land of Nothing. Image: Don Pinnock

The only road in the Land of Nothing. Image: Don Pinnock

The only road in the Land of Nothing. Image: Don Pinnock

Signs on the Skeleton Coast are so rare they become objects of interest. Image: Don Pinnock

Signs on the Skeleton Coast are so rare they become objects of interest. Image: Don Pinnock

The elemental beauty of the place is at the same time entrancing and malevolent. I hugged the ribbon of road, aware of a land utterly antithetical to human life. If you were stuck on this coast beyond help, the sun and wind would suck you to a husk within days and worry your desiccated bones for 1,000 years.

There is life, of course: tenebrionid beetles, chameleons and lichen surviving on water gleaned from sea mist. There are gemsbok, jackals, brown hyenas, desert elephants and even lions in dry river beds and around 75 species of seabirds. And seals.

We smelled them before we saw them at Cape Cross. The sight of about 100,000 of these sleek, grumpy creatures all going “arf” up and down the tenor scale was overwhelming. They’re not afraid of humans and showed a fine set of sharp dentures if we approached too close.

The stench and clamour of thousands of Cape Fur seals is overpowering. Image: Don Pinnock

The stench and clamour of thousands of Cape Fur seals is overpowering. Image: Don Pinnock

Here again, the stench and clamour of thousands of Cape Fur seals. Image: Don Pinnock

Here again, the stench and clamour of thousands of Cape Fur seals. Image: Don Pinnock

We turned in at a fisherman’s camp called, appropriately, St Nowhere run by Danie van der Westhuizen. It had been his salt mine, but transport got too expensive so now it’s a campsite with some prefab cottages. As the wind rattled the tin roofs and flung sand, we eyed the unprotected campsites with trepidation. If you erected a rooftop tent in that it would pop like a party balloon.

“Is there somewhere else around here we can stay?” one of our party asked, querulously.

“Ja, sure,” said Danie. “It’s 150km down the coast. But the big cottage here has five rooms and is unoccupied right now.” We had no choice. Two fishermen offered us some geelbek, which we grilled, and together with the Gordon’s gin from Kamanjab, the evening improved markedly.

At St Nowhere accommodation is simple but in the vastness most welcome. Image: Don Pinnock

At St Nowhere accommodation is simple but in the vastness most welcome. Image: Don Pinnock

Our campsite at Spitzkopppe was dwarfed by magical granite boulders. Image: Don Pinnock

Our campsite at Spitzkopppe was dwarfed by magical granite boulders. Image: Don Pinnock

That night the wind howled round the prefabs and icy Atlantic breakers growled 50m away. A warm sleeping bag on a soft mattress felt like heaven. In the morning the gale had stopped, the beach had no footprints and the sky was baby blue. We were sorry to leave. But another adventure beckoned.

After briefly sampling the urban pleasures of Swakopmund – good coffee and some excellent restaurants – we headed east in search of the Spitzkoppe mountains. Behind us the desert seemed to hover like an inchoate monster in a half-remembered dream.

On the flat plain near Usakos, the mountain was easy to see: a soaring mound of granite looking like the Matterhorn in the wrong hemisphere. After the unrelieved flatness of everything around for hundreds of kilometres, camping in the embrace of the mountain’s muscular arms was a hug of pure happiness.

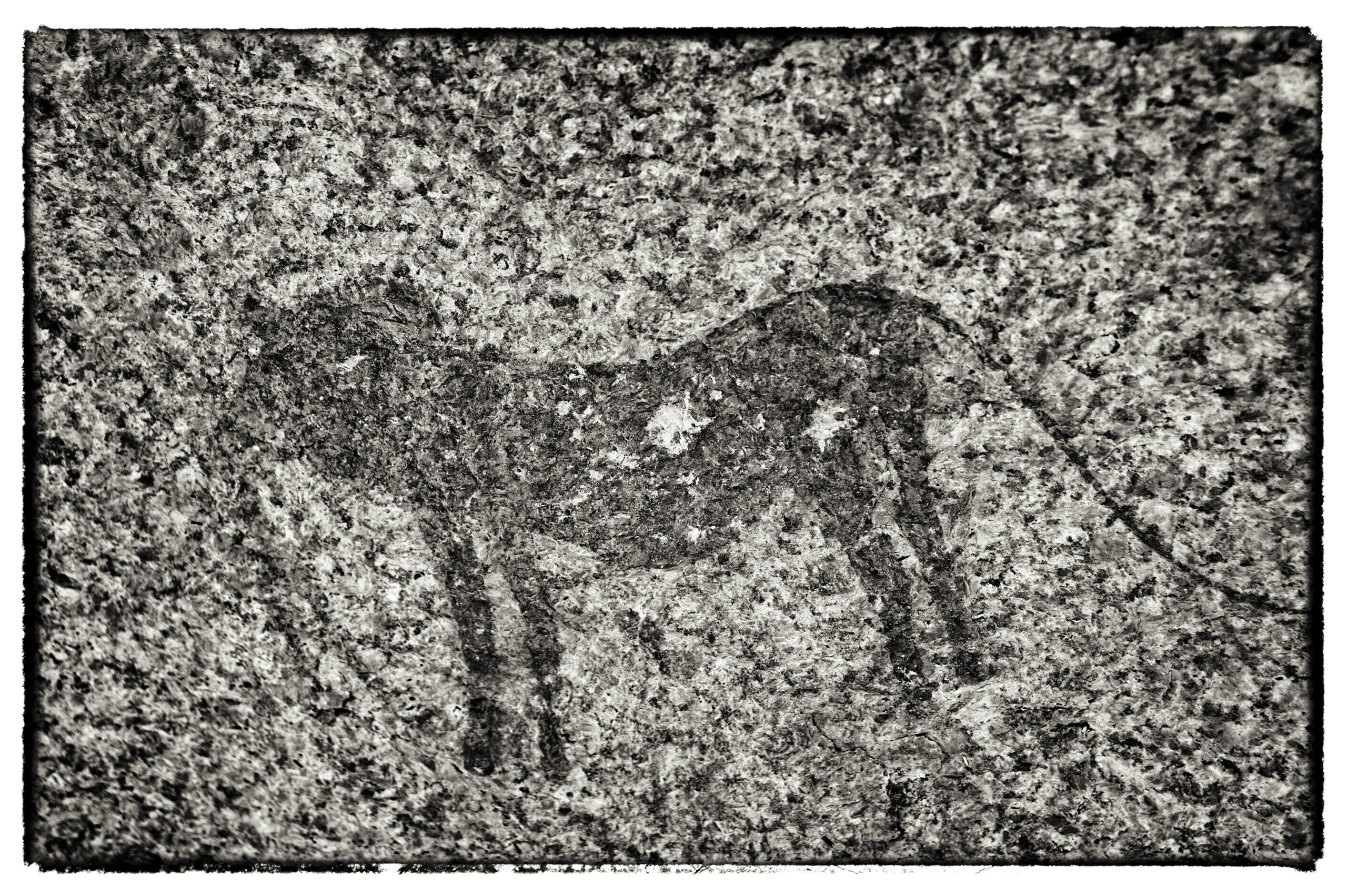

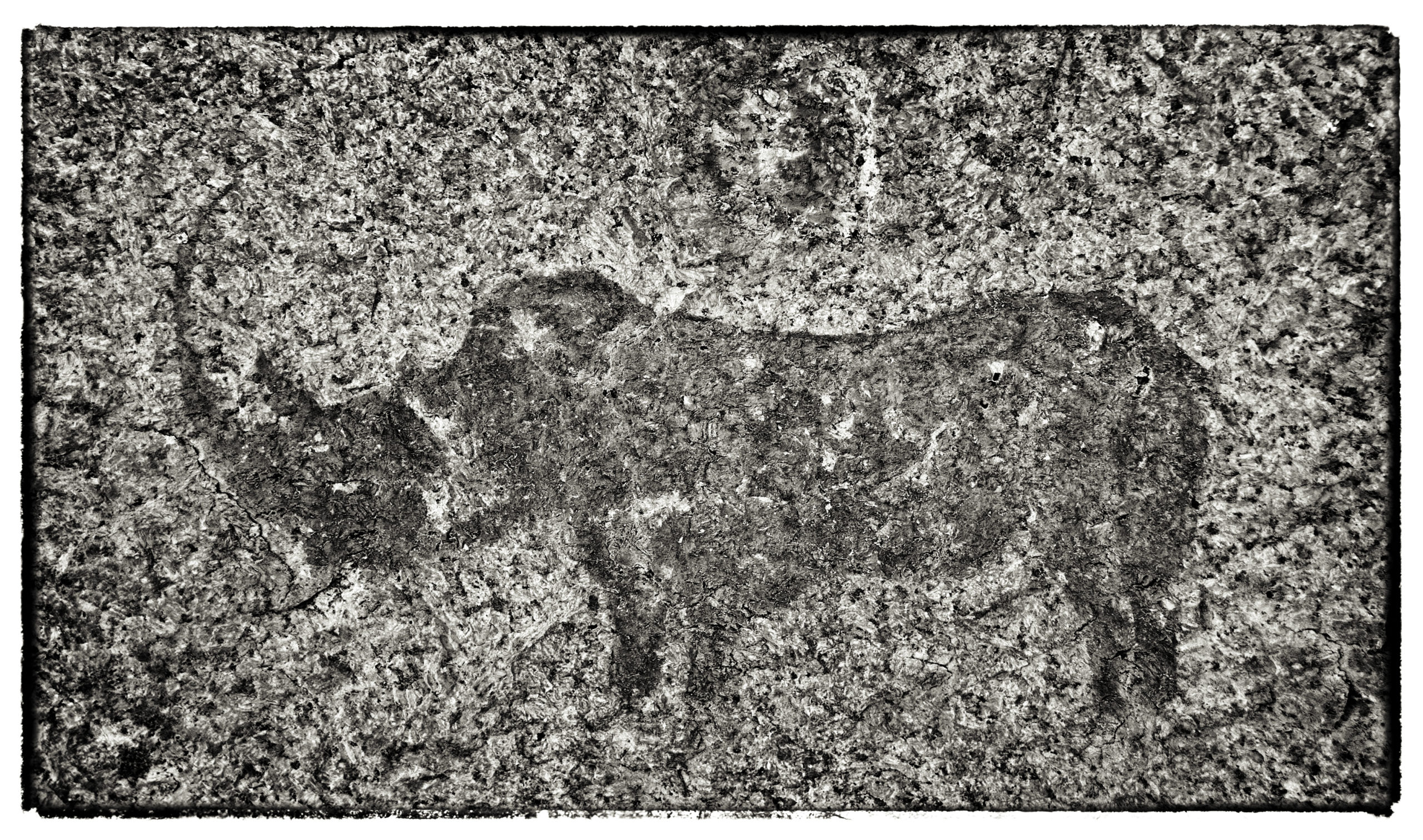

Spitzkoppe rock art. Image: Don Pinnock

Spitzkoppe rock art. Image: Don Pinnock

Spitzkoppe rock art. Image: Don Pinnock

Spitzkoppe rock art. Image: Don Pinnock

Spitzkoppe are saturated with strange magic. As the many children clamouring to sell crystals at the camp gates made raucously clear, it’s a source of all manner of glittering gems. If you know what to look for and where to look, there are also fields of ancient stone tools. In a cave we found the painting of a very long, sinuous snake and, at its head, a dancing shaman with a head-dress like a cockatiel.

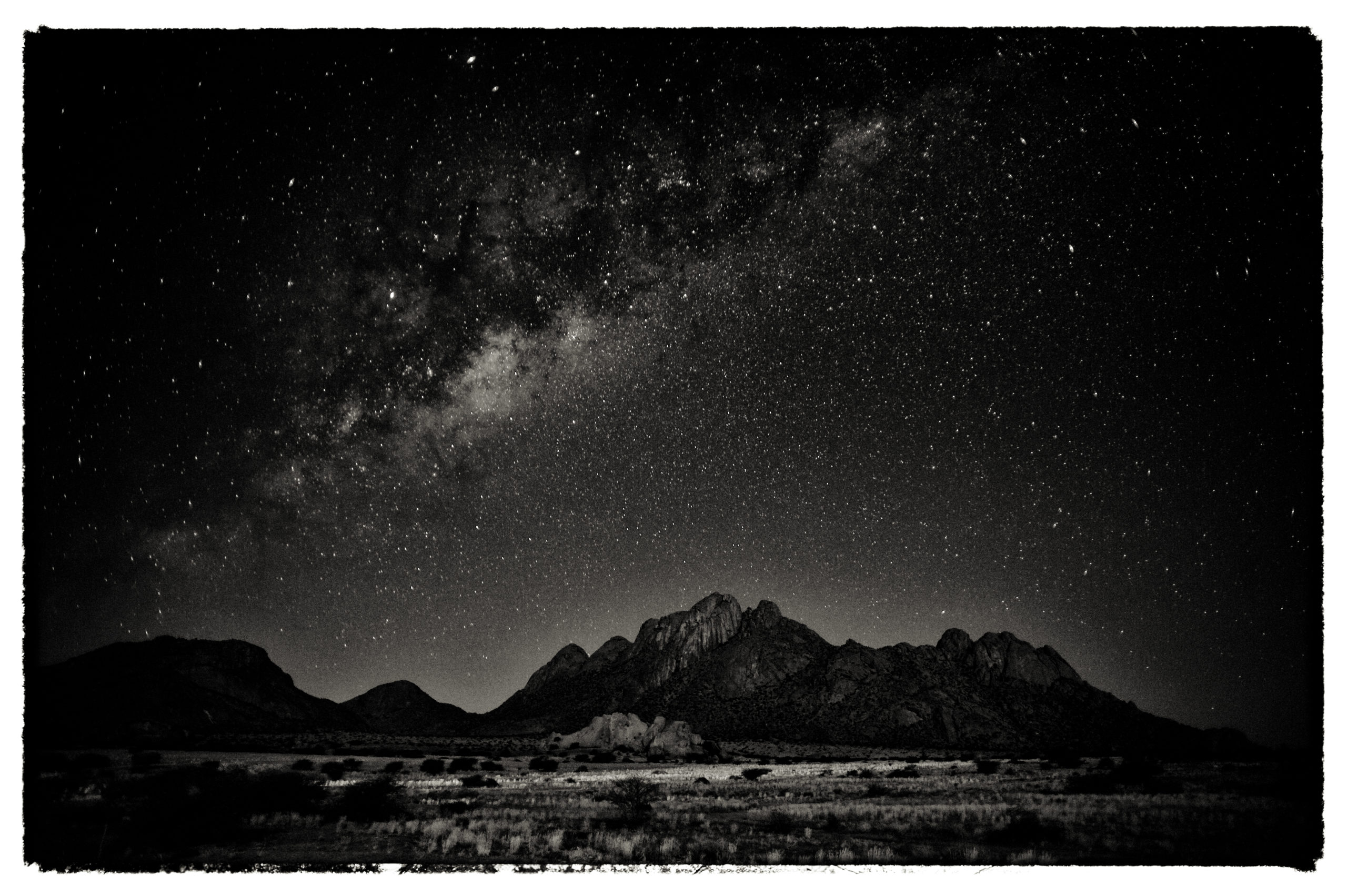

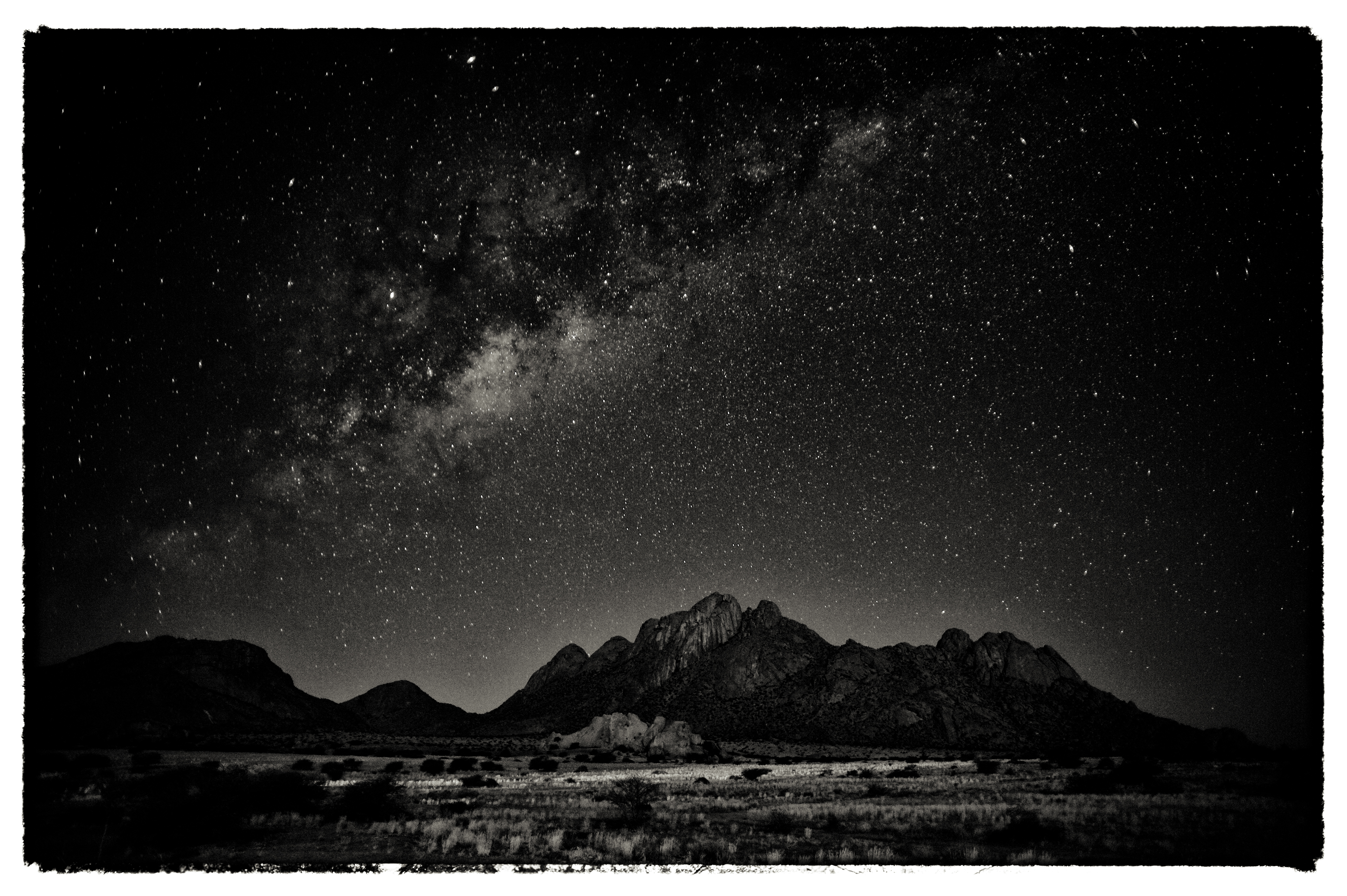

As night fell, the desert unveiled a sky glowing with more stars and galaxies than seemed possible to see – and so clear they twinkled at the very edge of Earth’s rim across the plains.

Image: Don Pinnock

Image: Don Pinnock

Night visitor: a spotted genet. Image: Don Pinnock

Night visitor: a spotted genet. Image: Don Pinnock

Camping among the boulders of Spitzkoppe is a surreal experience. Image: Don Pinnock

Camping among the boulders of Spitzkoppe is a surreal experience. Image: Don Pinnock

Deep in the night strange sounds around the camp had me tiptoeing down the rooftop tent ladder, flashlight and camera in hand. The prowler, so unconcerned that it nearly walked across my feet, turned out to be a large spotted genet. Or was it the shaman in disguise?

There’s a really beautiful lodge at Spitzkoppe, designed by architect Ronnie Barnard and run by his daughter, Janine, that seems to add, rather than detract from the area’s magic. But that’s another story.

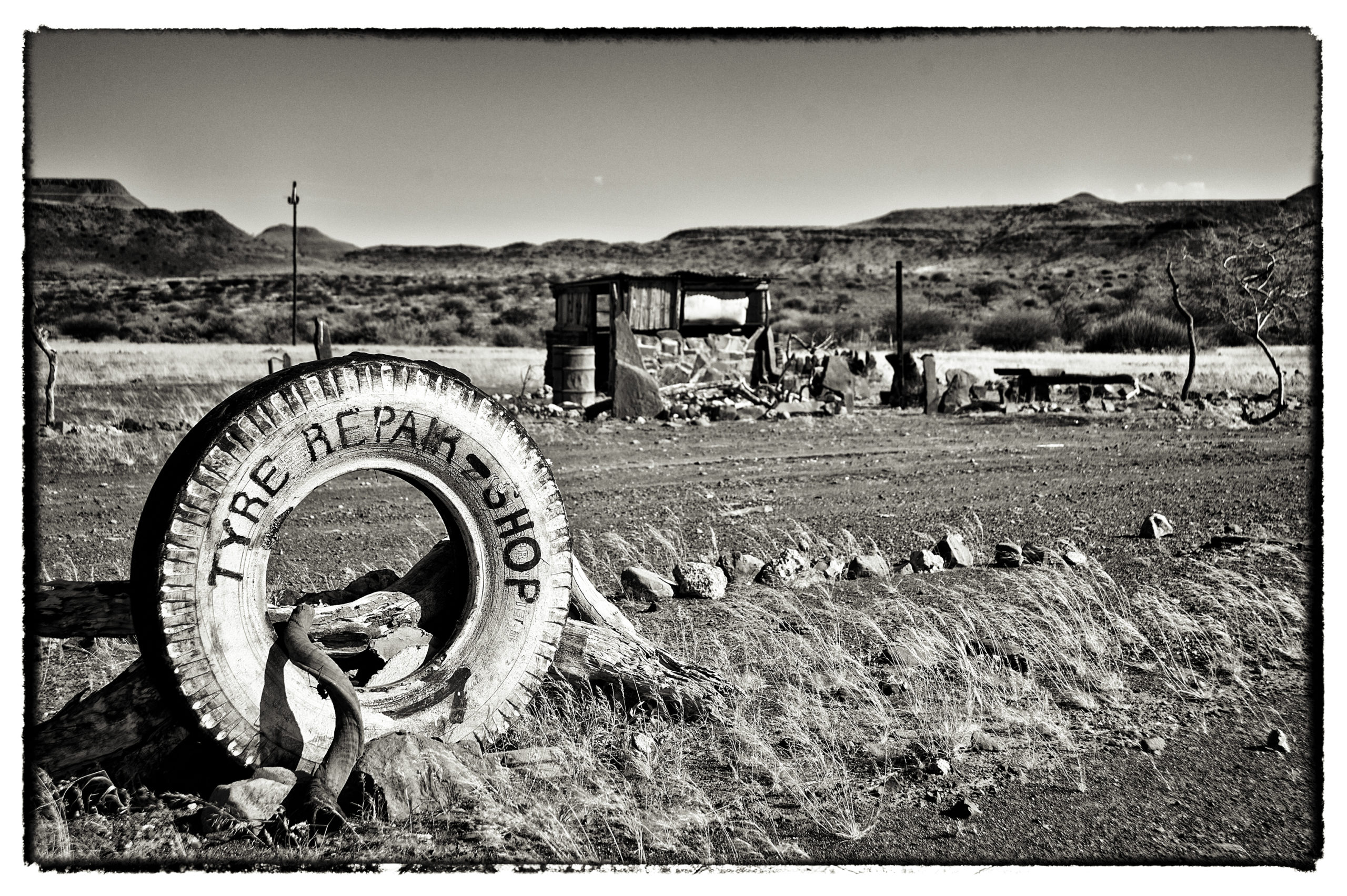

Roadside mechanical workshops in the Namib are not fancy affairs. Image: Don Pinnock

Roadside mechanical workshops in the Namib are not fancy affairs. Image: Don Pinnock

The sign, after an endless road, was irresistible. Image: Don Pinnock

The sign, after an endless road, was irresistible. Image: Don Pinnock

From Spitzkoppe, the highway to Windhoek via Okahandja was pretty monotonous. We’d been on the road camping rough for many weeks by that stage and heading for a city was somehow disconcerting. We’d booked a campsite just outside Windhoek, but my wife, Patricia, gave me a long, hard look and said: “Keep going.” By then, I guess, she deserved a hotel room with a hot shower and a comfortable bed with sheets. DM/ML

Image: Don Pinnock

Image: Don Pinnock