If we have one thing in common, it is the fact that we are all “mall rats” now. Sure, the few spend a lot, while the rest wish they could spend something. But what we all need can now be found at the local mall.

Surely we now need to ask the question: “why malls?” And surely that will provide a more significant material basis for debating the significance of these events than the political tropes derived from outdated largely Western theories of revolutionary change that we use as lenses for making sense of our complexified context.

There is near complete consensus among those who think about our economy that since 1994, two particularly important inter-linked dynamics have shaped our economic development trajectory — namely, consumerisation and financialisation. As the manufacturing sector has gone into decline, economic growth has been driven largely by consumption (consumers who buy more stuff).

That, however, would not have been possible if consumers did not have money. If the numbers of employed people are not rising, where does the money come from for all these increases in consumption? The answer is debt. Without massively expanding the amount of debt available to the expanding, increasingly multiracial middle class, the consumption-driven growth we have seen since 1994 would not have been possible. This, in turn, explains why the economy financialised.

Financialisation takes place when finance rather than primary production (mining, agriculture, etc) and manufacturing makes the biggest contribution to GDP growth. Unfortunately, services and finance-driven growth are not job-creating growth. Nor do they facilitate wealth redistribution — indeed, leaving existing land and property ownership intact is essential for the securitisation of the extended debt portfolios. Hence our so-called triple challenge — the persistence of poverty, unemployment and inequality.

At the core of South Africa’s Biggest Looting Campaign — better known as State Capture — was a political project to redirect the rents generated from financialisation and consumerisation into the hands of a political elite that felt excluded from the centres of financial power. Brian Molefe made that very clear during his remarkable testimony at the Zondo Commission about setting up a new bank for black capital; and the Gupta-compiled cheat sheet that Des van Rooyen was given just prior to his “weekend special” tenure as minister of finance included setting up a new state-owned national bank. And don’t forget the hoo-ha about the Reserve Bank’s so-called independence that our current Public Protector instigated.

What began as financialisation and consumerisation after 1994 became grand-scale looting during the State Capture years as the Zupta-centred power elite became impatient with “White Monopoly Capital”. When no one went to jail, everyone else was entitled to assume that looting is the South African way. (And now we debate whether this is insurrectionary... but I run ahead of myself.)

What needs to be recognised is that consumerisation and financialisation depended on the total spatial restructuring of consumption within South Africa’s urban centres. This was achieved by explicitly proliferating the construction of malls (many funded by the Public Investment Corporation) and concentrating the location of the supermarkets within these malls (funded mainly by private banks). The result was what UCT researcher Jane Battersby calls the “mallification” and “supermarketisation” of consumption.

Following the research by Battersby, just before the democratic era began, in 1992 less than 10% of all food was sold via the large supermarket chains in South Africa. The neighbourhood shops (the corner “caffee” and veg shop) and informal sector are where we bought most of our food in 1994. Only 10 years later, 60% of our food was supplied via the supermarkets. By 2010, 68% of all food was sold via the supermarkets (the highest in the world) and by 2017 75% of all groceries were sold via the supermarkets — the rest was distributed via the informal sector. However, without “mallification” this would not have been possible.

Retail space in 1970 was only 207,000m². However, as Battersby’s research shows, by 2002 it was more than five million square metres, and by 2010 a staggering 18.5 million square metres of retail space had been constructed. The proliferation of shopping centres after 1994 resulted in 1,053 by 2007, and then nearly doubling to 1,942 by 2015.

For those who think this was demand-led via the market, think again: total numbers dropped from 45,489 people per mall in 2007 to 28,321 in 2015. Overproduction because of easy access to finance has resulted in increasing amounts of empty space in malls. South Africa is fifth in the world when it comes to numbers of shopping centres. Shopping centres occur mainly in urban centres on land that needs to be zoned for this purpose by local government.

Even though local governments have no powers to determine the supply of food, by actively promoting mallification and supermarketisation, they have inadvertently been the primary drivers of restructuring food distribution to the majority of South Africans since 1994. And this has become synonymous in the minds of local politicians with “local economic development” (and more recently “township economic development”) — I recall the deputy mayor of Stellenbosch once saying to me: “How can we have development in this town without a mall?” Now we have two, and Stellenbosch is more unequal than ever.

Malls and supermarkets were the spatial fix that was needed to make consumerisation and financialisation work. They were also needed to reinforce the phantasmagorical consumer culture that has become the secular religion of the new debt-ridden, car-based, multiracial middle class that loves to “drive to park-n-shop”. But it was also needed to herd the urban poor (employed or not) into the proliferating “township malls” (promoted by local governments as “local economic development”).

The dramatic increase in the payment of social grants to 17 million South Africans created a consumer spend of R150-billion per annum. Christo Wiese may present himself as “bringing retail services to the poor”, but it was the social grants financed by the taxpayer that he cleverly raked into his gigantic treasure chest (which he later realised he needed to share by enriching his BEE partners).

Consumers needed to be herded into tightly controlled spaces to buy stuff from increasingly concentrated retail chains financed by powerful public and private financial institutions. The Public Investment Corporation (PIC), a public entity that invests government pension money, led the finance group that funded mallification, and the private banks funded supermarketisation. Centralised retail chains in centralised malls suited a centralised financial system. The neighbourhood shops (which used to be key donors for local civil society groups) went into decline and with them a key economic mainstay of community life. In short, consumerisation and financialisation led to mallification and supermarketisation which, in turn, has ripped the social guts out of local communities.

So the next question is whether these malls are, in fact, the engines of local economic development that developers, financial institutions and local politicians make them out to be. A remarkable Facebook post by Djo BaNkuna from Pretoria entitled The Dark Side of the Current Mall regime is worth quoting in full on this topic:

“A Mall is NOT development. Township Malls are instruments of poverty and exploitation. The sole purpose of a Mall is to permanently extract liquidity in the community ecosystem to the rich suburbs and offshore accounts. Once a Rand enters a Mall, that community will never see that money circulating in that community again. A Mall is like a fishnet, once the fish enters, it will never see the ocean again. Communities are poor because they do not have enough money in circulation. Shoprite shall never buy magwinya from Mrs Zulu, second tyres from Thabo or hire a cleaning company from Soshanguve. Mall money only travels in one direction from the community to the Mall, from the Mall to their wealth owners away from the township.

“One of the biggest mistake government is making is to continue to allow the proliferation of Malls in their current format. Members of the community do not have an emotional connection to the mall. For many, each visit to the Mall is like a visit to the zoo where they observe what they can never own. The Current Mall regime treat community customers as visitors than collaborators. They do not know who owns the mall, who sells in the Mall and who made the products being sold in the Mall. The Mall’s presence in the township is limited exclusively towards extracting value in the form of money. That is why Malls are seen as an external creation than a true part of the community (maybe with the exception of Maponya Mall).

“So, our celebration of the building and opening of a Mall is myopic, ill-educated and misguided. The celebration demonstrates how poor our comprehension and understanding of the basics of labour exploitation and profit making.

“What must be done? Introduce a policy on 70% local for certain goods/merchandise, force Malls to set aside 30% of floor space for local business. Restrict big cartel anchors like Checkers/Shoprite to one shop per mall per 20km radius. Do something! It is more complicated, but that is a start. Until then, just like cattle, we are grazers and consumers of the worst kind. We are producers of dung. As you know, cows end up in the slaughterhouse. We are busy celebrating our ignorance.”

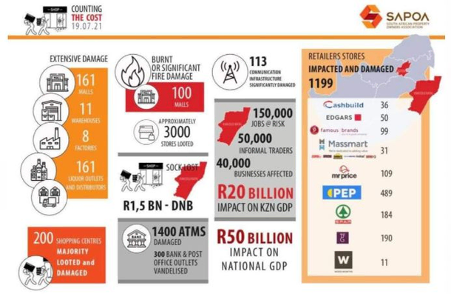

(Source: Sapoa)

According to the SA Property Owners Association, 161 malls were intensively damaged, 100 burnt and more than 1,000 retail stores damaged, with Pep, Game, Spar and Mr Price the most targeted. (So much for the argument this was a food riot! People need clothes.)

So, we return to the question of how best to characterise what happened during that fateful week after Jacob Zuma was imprisoned. Those who argue that it is problematic to characterise the events as an insurrection have a point. An insurrection implies an orchestrated act of violence aimed at collapsing or overthrowing a state. Some of the tweeters may have used this rhetoric, but there is no evidence that the logistics were in place to execute such a plan.

There is more than enough evidence, however, that there was in fact a group of instigators with a political strategy who triggered mass looting by sabotaging key high visibility targets with the explicit purpose of subsequently broadcasting these acts via social media. Then, following the wildfire analogy, the looting spread uncontrollably as a conglomeration of people who did not have an explicit political agenda (criminals, petty opportunists in their Mercs and SUVs, and a large number of desperate people who just took the gap and made good) seized the opportunity of a dazed (and probably divided) security establishment to attack the malls.

Sedition, therefore, best describes what the instigators had in mind. Sedition is organised action aimed at calling for or catalysing violent acts against the state to achieve a political objective. This may intentionally or unintentionally catalyse an insurrection or even a coup d’état, but this may not have been the original explicit intention. Sedition could also be an assassination or sabotage of infrastructure to secure a concession.

In short, what started as an act of sedition to secure Zuma’s release, triggered waves of mass looting of malls by many whose intentions were primarily acquisitive. But this then begs the question: why malls? Don’t get me wrong: I am not suggesting the attackers of malls understood that malls have become the epicentre of a failed post-1994 economic development strategy that has resulted in the persistence of poverty, unemployment and inequality. No.

Malls were attacked because they have become the epicentre of everyday economic life in post-apartheid South Africa — it was not factories that were attacked, as often happens in industrialised societies (because we did not build them). Malls are, quite simply, where the stuff of everyday consuming is now located. And as Djo BaNkuna put it, “the community do not have an emotional connection to the mall”.

That may change now, because the politics of either looting or protecting our local mall has now become the epicentre of middle-class politics. That does not mean working-class people are not at the barricades of protection. But in the final analysis, the sedition failed because the mall-centred consuming middle class felt attacked. Who would have thought back in 1994 after buying bread at the local “caffee” that by 2021 community organising would be about protecting the malls, complete with T-shirts boasting #no looting in my town?

What the July 2021 “Zumite sedition” and subsequent mall looting should signal for us all is the end of an economic development strategy premised on debt-financed consumerism that was spatially fixed through twinned strategies of supermarketisation and mallification.

To think these grocery fortresses (that need protecting now by police and army) surrounded by masses of poverty-stricken people in the most unequal society in the world can continue as lodestars of local economic development is a form of extreme stupidity. It is now, also, a security risk.

The solution lies in redirecting financial resources into the “real economy”, with a focus on production. We also need to rebuild the local neighbourhood retail centres and corner shops. We should have done this long ago, but as Djo BaNkuna proposes, it might not be too late. The PIC could take the lead by refusing to fund the next mall. DM