Doctors, lawyers and other professionals display their university degrees with pride in reception areas and offices, largely to reassure patients and clients that they are qualified to perform specialist tasks.

Framed certificates of accreditation and training courses are also on display in vehicle dealerships and mechanical repair workshops for similar reasons.

So what reasons might there be for concealing or declining to produce proof of your hard-earned professional qualifications for all to see?

This is why it is rather puzzling that Cape Town hazardous risk consultant Terence Thackwray — who helped to authorise the fire and explosion risk assessment studies for the multibillion-rand Karpowership gas-to-electricity plans — has ignored repeated requests from Our Burning Planet to see a copy of his BSc chemistry degree.

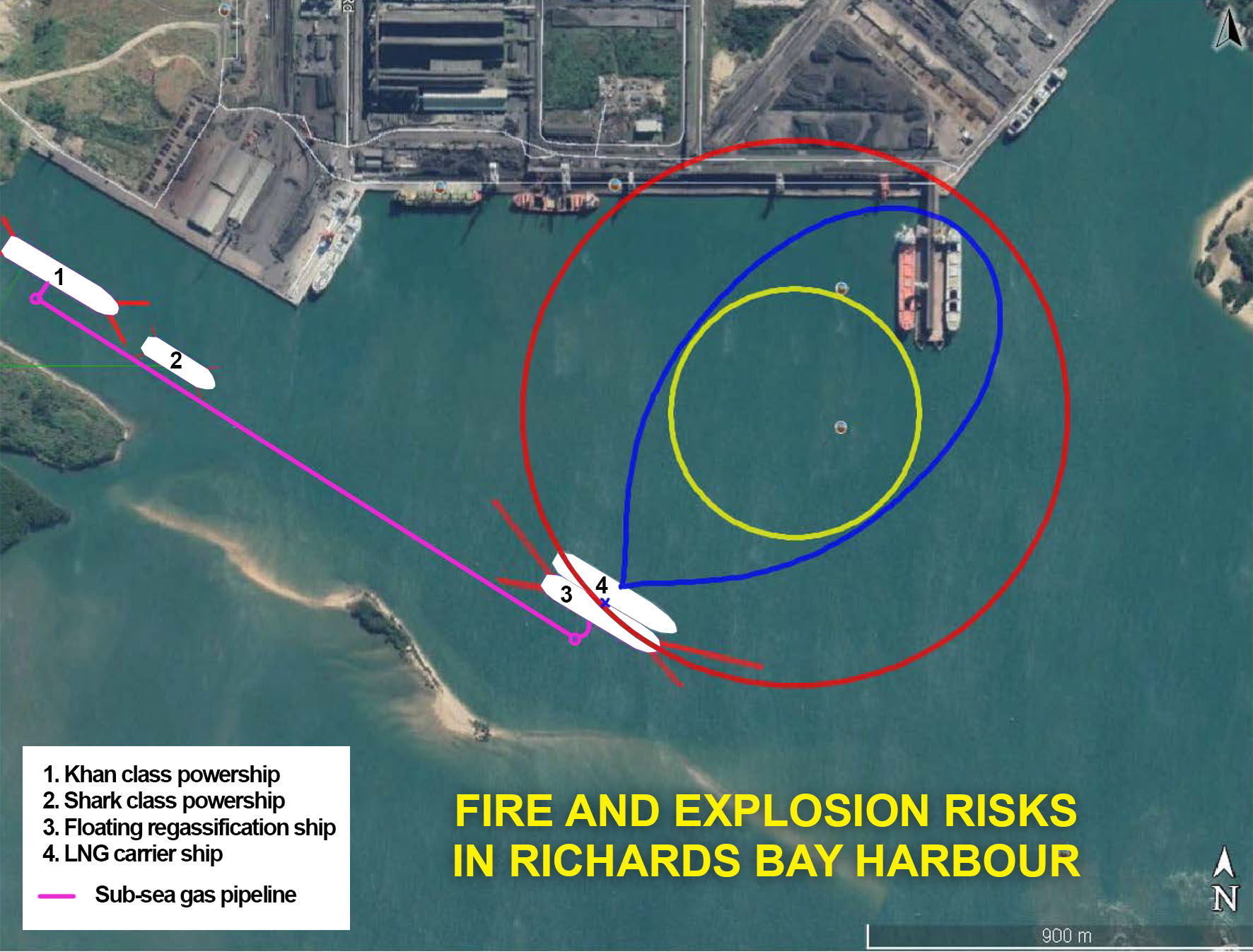

A February 2021 map prepared by Claude Thackwray indicating the potential consequences of a vapour cloud explosion from Turkish power ships in Richards Bay harbour. The blue contour shows the extent of the flammable vapour cloud, though the human safety risks of the yellow and red contours are not explained clearly in the report. (Image source: EIA report)

A February 2021 map prepared by Claude Thackwray indicating the potential consequences of a vapour cloud explosion from Turkish power ships in Richards Bay harbour. The blue contour shows the extent of the flammable vapour cloud, though the human safety risks of the yellow and red contours are not explained clearly in the report. (Image source: EIA report)

Terence Thackwray and his father, Claude, worked together on three recently revised risk assessment reports as part of the 20-year Turkish “emergency power” plan for Eskom.

The reports, by Major Hazard Risk Consultants CC, have been submitted to the government as part of the long, drawn-out environmental impact assessment (EIA) process.

The assessments were conducted by Claude Thackwray, who is listed as the technical signatory, and then checked and approved by his son Terence, who also signed a separate declaration under oath at Melkbosstrand Police Station on 22 October 2022 describing himself as the independent specialist for the risk assessment project.

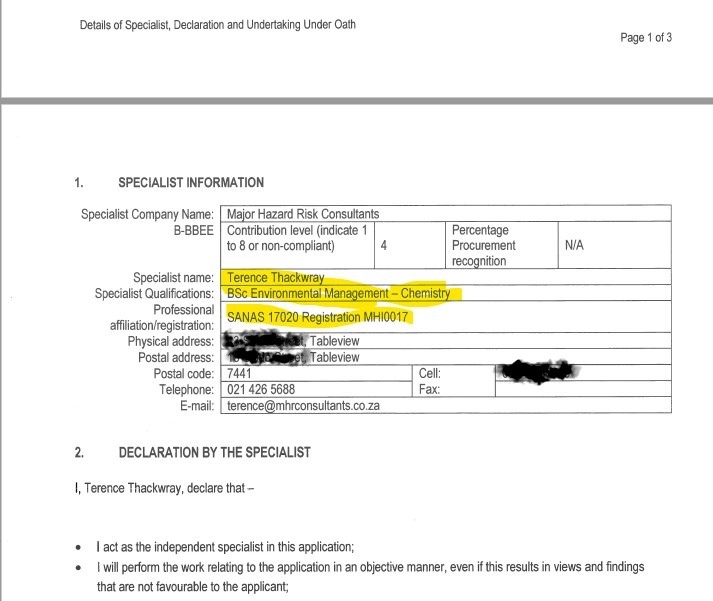

In this sworn declaration, Terence listed his academic qualification as “BSc Environmental Management (Chemistry)”.

Terence Thackwray’s sworn declaration about his academic qualifications dated October 2022. (Image: Supplied)

Terence Thackwray’s sworn declaration about his academic qualifications dated October 2022. (Image: Supplied)

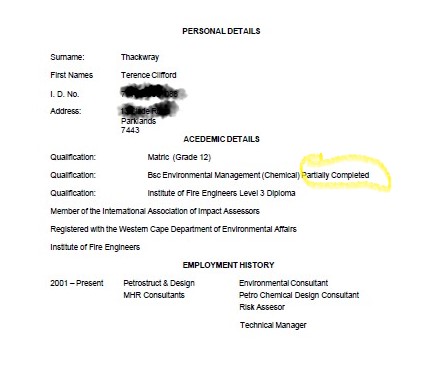

This was the declaration that drew the attention of Our Burning Planet, because in a previous bundle of documents submitted to the government in February 2021, Terence’s curriculum vitae recorded that his chemistry degree was only “partially completed”.

A CV submitted in 2021 states that Terence Thackwray’s B.Sc degree is ‘partially completed’ (Image: Suppiled)

A CV submitted in 2021 states that Terence Thackwray’s B.Sc degree is ‘partially completed’ (Image: Suppiled)

To clarify whether Terence had been awarded the degree, we sent messages last year to the Thackwrays and to Karpowership environmental assessment practitioner Aletta “Hantie” Plomp. In her written response, Plomp stated that Terence had completed the degree in 2019.

We thanked Plomp for this clarity, but subsequently requested her or Terence to kindly send proof: a copy of the degree certificate showing his name, tertiary institution, degree description and the date it was awarded.

Complete silence

Oddly, there has been complete silence from the Thackwrays and Plomp, following our request on 18 January.

What could be the reason for this?

Conceivably, Terence may have been insulted by our request for proof. But why not dispose of the question and any aspersions by providing a copy of the degree certificate?

So, earlier this week, this writer made a final effort to elicit a direct response via telephone.

But his dad replied and declared brusquely: “I’m not talking to you. Bye.”

Terence did not answer his cellphone a few minutes later; neither did he respond to a subsequent WhatsApp message.

And there was no response via cellphone or email from Plomp, who is in overall charge of Karpowership’s EIA application process.

So, what is the big deal? Does it matter whether Terence Thackwray has a BSc degree or not?

After all, his father’s company is registered by the Department of Labour as a “Type A” Approved Inspection Authority to conduct Major Hazard Installation (MHI) risk assessments. The company also has a similar certificate of accreditation from the South African National Accreditation System (SANAS). Both certificates are valid until 2025.

A Department of Employment and Labour accreditation certificate issued to the Thackwrays’ company. (Image: Supplied)

A Department of Employment and Labour accreditation certificate issued to the Thackwrays’ company. (Image: Supplied)

A South African Accreditation System certificate issued to the Thackwray’s company. (Image: Supplied)

A South African Accreditation System certificate issued to the Thackwray’s company. (Image: Supplied)

The first issue of concern is Terence’s apparent reluctance to produce proof of his academic qualifications. He made a declaration under oath at a police station that he has this degree but this appears to contradict the previous curriculum vitae statement that the degree was partially completed.

His failure to produce it after repeated requests appears incomprehensible.

Perhaps he is travelling abroad and does not have a copy to hand. He could be ill or ill-disposed to entertaining media requests, but in the absence of any responses from him, those reasons are not known.

The second issue concerns the critical importance of specialist personnel being suitably qualified to assess the potential death risk factors in the event of a major explosion or fire.

Outlining some of the pertinent history in a recent MHI safety report, senior South African chemical engineer and risk assessment specialist Debbie Mitchell referenced the Bhopal and San Juanico chemical gas disasters in India and Mexico, respectively, in 1984 and the Seveso chemical accident in Italy in 1976 among several catastrophic events that have underlined the need for tougher regulation of major hazard installations (MHI) globally.

“In many cases (eg Bhopal), this was compounded by the fact that the public as well as the emergency services had no idea of the types of chemicals on the sites and therefore no idea of how to respond when the events occurred.

“In an attempt to prevent the recurrence of such disasters, there was a trend in the 1980s and 90s around the world to implement legislation to control such situations.”

Stricter laws

The so-called Seveso Directives in Europe and the introduction of new MHI regulations in the UK were good examples of how stricter laws had been implemented across the world, she said.

“The most recent round of legislation is focused on requiring companies to provide evidence that they are managing their risks adequately. When the South African laws were compiled, the authors took cognisance of the regulations in other countries and any difficulties that had been experienced … Ultimately the objective behind registering a site as an MHI is to ensure that the local authorities know what hazardous chemicals and hazards are out there, have emergency plans in place in case of an incident and have adequate information to control developments.”

Visit Daily Maverick's home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Coming back to the Turkish powerships plan, large volumes of liquid natural gas would be transported to and burnt inside three of the country’s largest ports. Yet, despite rigorous safety precautions by Karpowership, accidents still happen. The harbour personnel and general public are entitled to a thorough, accurate and independent assessment of those risks.

Third, there are mandatory requirements to ensure that South Africa’s approved inspection authorities comply with the relevant national and international standards — SANAS/ISO/IEC 17020:2012.

As set out in the Department of Labour/SANAS technical document TR 54-06, a technical manager for these inspection authorities must (at minimum) hold a university degree, bachelor of technology or higher national diploma in either chemistry or engineering.

Risk assessors are also required to hold a “technical or scientific tertiary qualification with at least 2 years of tertiary chemistry included in the qualification”.

The importance of professional engineers and technicians having the requisite academic training for specialist tasks that can affect public safety was further underlined in a recent court case in which an Umgeni Water employee lost his job after presenting false academic qualifications to his employer.

Fourth, there is a legal grey area concerning whether professional MHI risk assessment personnel are required to be registered by the Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA) — a statutory body established in terms of the Engineering Profession Act (EPA), 46 of 2000.

The ECSA’s main role is to regulate the engineering profession, including the accreditation of engineering programmes and registration of professional engineers in specified categories.

A search function on the ECSA website indicates that neither Claude nor Terence Thackwray is registered as a professional chemical engineer — though the council suggested in a recent media statement that ECSA registration is not mandatory.

Nevertheless, says the council, South Africa is a signatory to three international accords that govern the recognition of engineering educational qualifications and professional competence.

“It is therefore incumbent upon any institution performing engineering work to make use of quality assured engineers in the interest of public safety.”

Perhaps Terence Thackwray has been awarded the relevant BSc chemistry degree required for his specialist tasks, but the answer to that question has not been resolved so far. DM/OBP

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REeWvTRUpMk

A South African Accreditation System certificate issued to the Thackwray’s company. (Image: Suppiled)

A South African Accreditation System certificate issued to the Thackwray’s company. (Image: Suppiled)