‘I am South African, a ‘Trevor Noah South African,’ not an ‘Elon Musk South African’,” is my response when asked about my accent in America. How I speak – I don’t sound American and, like many South Africans, unconsciously ja a lot – comes up often these days as I canvass for Democrats for the upcoming US elections.

Canvassing is trying to influence a voter on how they’ll vote in an election by connecting with them in person either at their home, by phone, or by text. Direct contact is arguably the most effective way of impacting people as they consider their vote. Voter turnout for those who’ve been canvassed is higher than for those who weren’t, reputedly as high as a six-point difference.

When I canvass, I knock on strangers’ front doors to talk politics. Which, in the fraught US political climate, qualifies as Extreme Halloween. The trick, at a minimum, is not getting the door slammed in your face while presenting your candidate’s promotional material. The treat is having an in-depth exchange with the voter: listening to their concerns, suggesting why they should support the candidate in question, and learning whether or not they’d actually vote for said candidate.

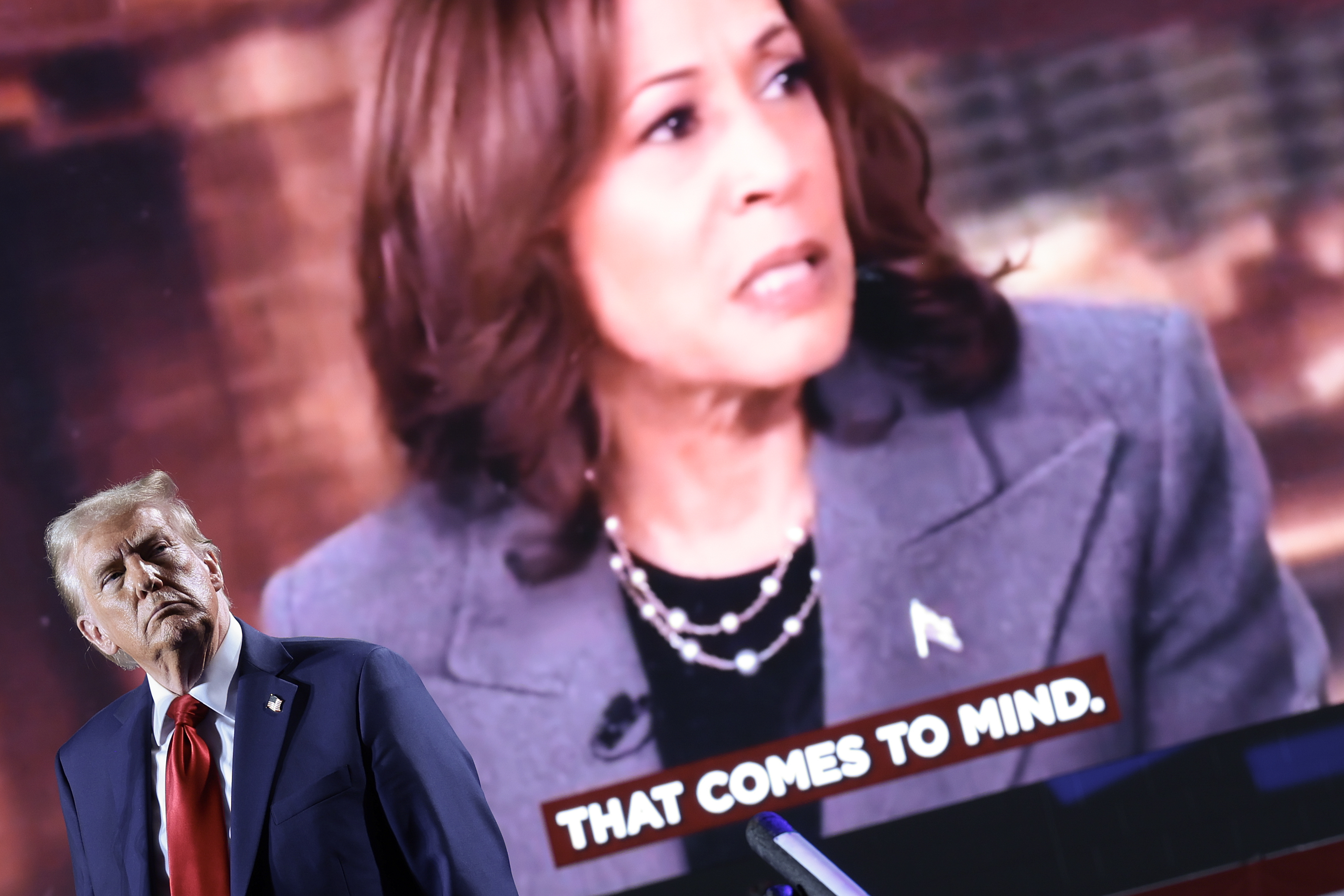

I’ve canvassed regularly for Democrats up and down the ballot in suburbs across Maryland, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Virginia on weekends since 2018. At present, I’m mainly canvassing in Pennsylvania, the state widely acknowledged as the “swingiest of the swing states” in this year’s presidential election. For both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump, their paths to victory in the electoral college, the quirky, antiquated system that determines who actually wins the presidency, are tricky without winning Pennsylvania’s 19 electoral college votes.

I canvass strictly as a volunteer, often with one of the many democracy-promoting grassroots groups that have sprung up in America these last years. The buzz, enthusiasm, and camaraderie found in these civic-minded groups remind me of the spirit of the United Democratic Front (UDF)-supporting networks in 1980s South Africa.

Meeting voters through canvassing lifts me. As this year’s campaigns obsess with the horse race of the elections, it’s the people I’ve met who stay with me: their faces, their neighbourhoods, and the stories they tell about themselves and their lives in America.

The front doors of most American homes are readily accessible. American homes, whether working class, lower or upper middle class, or even wealthy, are typically not shielded behind fences or big walls with electric wiring or broken bottle pieces on top. If American houses are physically fenced off, it’s usually to enclose pets.

My favourite areas to canvass are “melting pot” suburbs, where new and less newly arrived immigrants live interspersed with native-born Americans. Residents here might not hire yard services but instead maintain (or not) their yards themselves.

A scene near Richmond, Virginia especially charmed me. Of the eight homes on this cul-de-sac, three featured on my canvassing list. A mixture of Ghanaian-American and white American families lived there. Front doors and garages were ajar as a cacophony of children rode bicycles or scooters in the cul-de-sac while others rollerbladed, jumped rope, or wrote with chalk. It was the American Dream at its best.

In another Richmond neighbourhood, homes were closed up, with curtains, blinds, or even towels pulled across the windows overlooking the street. Front doors were plastered with “No soliciting” signs and notices announcing the alarm system being used. I learnt from three different households, all black women who opened their doors to me, that their neighbours, mainly white families, were uncomfortable with their presence. One lamented how her outdoor decorations, including for Halloween, were always destroyed. An American flag she once flew was shredded overnight.

In Fredericksburg, Virginia, the first thing I saw when the door opened was the barrel of a gun. I froze in stunned horror. As I turned to flee, a woman appeared. She apologised vociferously for her gun being on top of her television by the door, with its barrel aimed at whomever stood on the doorstep. She explained she did this because she lived alone, the “neighbourhood was rough”, and she wanted delivery people regularly bringing her takeout food to “know not to mess” with her.

Multigenerational homes are a particular joy. Many times, these are new immigrant families, but not always. A grandmother, perhaps wearing traditional clothing, might open the door – even though she barely speaks English but is a native speaker of, say, Urdu or Spanish. The parents are probably at work, while the comfortably bicultural grandchildren, in T-shirts and cut-off or ripped jeans, come to help grandma at the door.

Many people are struggling. You sense this immediately from the condition of their yards.

A scraggly lawn, flower beds wild with long-dead blooms, weeds galore, an overflowing mailbox. Or askew or fallen-off digits amidst the others displaying the house’s number. Or cars with flat tyres parked in the driveway or on the nearby road. These people are preoccupied. Perhaps a family health crisis is under way. Perhaps someone lost their job. Perhaps they don’t care. Perhaps they can’t afford to care.

At a townhouse complex in Bensalem, Pennsylvania, I knocked on the door of a family with four registered Democrats. The mother, who spoke heavily accented English, answered and told me that they’d all be voting Republican this election – for the first time. She attributed the failure of her 13-year-old business to Democratic policies. She was bitter about renting in that development as they’d “previously owned a very nice, big house”. She and her husband were doing everything they could to keep their two children in college.

People can be astoundingly chatty with a stranger. A woman discussed her cancer treatments. I was told about an abusive husband whom a wife escaped by moving back in with her parents, along with her three children, and how their presence was stressing the grandparents even while they were happy to help them. Others describe their neighbours’ political views, saying “you shouldn’t bother” going to this or that home, while directing you elsewhere.

Some baulk at discussing how they vote, saying their preference is private. Canvassers have to respect this perspective. Interestingly though, readily revealing their political proclivity is the rule, not the exception.

Some holding different views are aggressive or behave nastily. Recent experiences in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, were particularly unpleasant.

“I hope you won’t be home when I come to your house,” spat a man with a scraggly beard when I knocked on his door.

At another door 10 minutes later, a ginger-haired man turned red in the face as he hollered, “You take all your (expletive) Democrat (expletive) and leave my (expletive) house!” as I sought to canvass his mother or mother-in-law.

The coup de grace was a man who assured me all in his household were Trumpers and then yelled at his neighbour across the road who happened to be in his yard, “Here’s another Kamala fan for you!” I mistook this to mean the man was a genuine Harris supporter, so I headed over there, even though this man wasn’t on my canvassing list.

As I approached his house, the second man screamed, “Don’t you (expletive) dare set foot on my property! Don’t you (expletive) come anywhere near me!” as the first man roared with laughter. I was glad to walk away.

This trilogy of threatening experiences in one canvass is, fortunately, rare. The worst I’d previously faced was being accused of being “a traitor,” “a communist,” and “dangerous”.

Usually, when the person who opens the door disagrees with the canvasser, they’re not deliberately insulting. They’re mostly polite, saying they’re “busy” or “not interested”. Or they just say they “vote another way”. People are generally civil and moderate; they don’t seem to want to project being extreme one way or another.

Yet it’s also deeply problematic that too many Americans are apolitical, “don’t care,” or “don’t think much” about politics. The degree of indifference is alarming. They say they’re put off by politics and disgusted with politicians, especially “career politicians”.

One man explained how anything on elections that arrived by mail went straight into his outside rubbish bin. Another man said he’d always voted, but now felt it made no difference which party was in power as “nothing ever changed or improved” so he wouldn’t bother with it again. Yet another offered that voting “only worked for white people” so he didn’t vote any more.

A 72-year-old Pakistani-American woman said she’d never vote again – despite voting in every primary or general election since she arrived as an 18-year-old in America.

US policies in the Middle East disgusted her, especially how Palestinian children’s lives were devalued. She felt that Americans only supported democracy when it suited them.

What about Mohammed Morsi in Egypt? And Imran Khan in Pakistan? Both were legitimately elected. No, she insisted, Americans aren’t really democratic. She and others in her community were “done with voting”.

In all such cases, I push back, saying that when indifferent, disgusted, or disillusioned folks don’t vote, they cede the floor. I project that life could get worse if the majority’s views aren’t represented and offer that the best way to shut down the views of those who don’t reflect most voters is to outvote them. I remind folks how a coin toss literally decided a Virginia State House race in 2017. Who votes and who doesn’t vote absolutely matters.

I was supposed to speak to the tenant in the trailer home of a 68-year-old Virginian, but she wasn’t there. The landlord and I started chatting. She, a pint-sized chain smoker who swore at least twice in every sentence, despised the then-president, saying that he reminded her of “every (expletive) bad boss” she’d ever had. It turned out she’d never voted and had no idea how to do so. There was still time for her to register. She hoped assorted family members would join her the next day in registering and then voting.

A young man in North Carolina told me he couldn’t vote as he was a newly released felon. Fortunately, I knew that North Carolinians who’d served their time and paid all fines could resume voting. He was thrilled.

Another encounter with former felons, this time in Virginia, was more sobering. They were unimpressed with being eligible to vote again. They just wanted to get jobs so they could provide for their families. A neighbourhood car wash business they’d started together didn’t generate enough income and their pasts made it feel impossible to get other work. They were frustrated. I urged them and their family members to vote, especially in state and local elections, precisely to get representation that better helped people in their situation.

Black women are reputedly the most reliable voters in America and my anecdotal experience confirms this.

In my years of canvassing, all the black women I’ve met say they never miss an election. In the one possible exception, the mother of this woman had died from Covid-19 in 2020 and her sister in 2021.

The woman was convinced that her family members had received substandard care in hospital, that neither of them would have died if they were white, and that both should still be alive. Black lives, she said, were expendable in America. Her mother taught her children to vote, but she herself didn’t think voting made any difference. Yet I left thinking that, despite her understandable bitterness, she might end up voting – to honour her mother.

A stint handing out sample ballots at a Maryland polling station reminded me how black women go to extraordinary lengths to vote. One woman took two buses to come and vote in a journey of over two hours; the reverse trip would take another two. She said she always made the effort because “people died so I can vote”.

A frail woman arrived with a driver and an assistant, both of whom were necessary to help her out of and into their vehicle and in and out of the polling station. An official could have come to facilitate her voting in the car, but the woman insisted on going inside as voting was “sacred”.

There is a puzzling intersection in this election between socioeconomics, race and gender. Sometimes race reinforces gender, other times it works against it. A black male voter volunteered that “if it’s black, I vote for it”.

I imagine there are whites who’ll similarly only vote for white candidates. Yet not all women will vote Democratic because a woman again tops their ticket. To the contrary.

The gap between how men and women vote will, however, be extremely pronounced and meaningful this election, not only because women’s reproductive rights are on the ballot.

In a Prince William County retirement community in Virginia, four older women told me independently – in one day – that they’d never again vote Republican, even though they’d each voted that way most of their lives. They were angry that abortion rights, something their generation had worked for and had assumed would exist in perpetuity, had been taken away from American women.

Undercurrents around gender manifest in provocative ways when canvassing, with split-loyalty households being especially fascinating. It’s enjoyable when such a couple can joke about how their votes “cancel out” each other’s. Women who vote one way will speak of wanting to persuade their husbands to vote differently, whereas I’ve found that men will sometimes gatekeep. Men have blocked me from talking to their spouses or daughters – even when the partner or daughter is clearly home.

The man of a household in Bensalem, Pennsylvania, insisted that they “weren’t interested” as they were “a Trump family”, while the woman at his side simultaneously acknowledged that she was one of two women on my list whom I asked to speak to at that address. The man hovered as we conversed; I appreciated that she couldn’t wait for our chat to finish. But she looked me in the eye as she said, “I will vote.” As I walked away, I praised the secret ballot.

Various forms of misogyny will be a factor in this election. An older male voter in Virginia, clearly a charmer, said he adored women. He had three daughters. He thought women were “far better people and company” than men. He loved being with women so much, he told me, that he had a female doctor, a female dentist, a female lawyer, and so on. Yet he admitted he’d been unable to vote for the first female candidate for president. I wonder how he’ll vote in this election.

A female voter, who told me she was a social worker and a Christian, wondered if women have the “right emotional temperament” to be president.

Immigration is another hot issue facing the electorate. A Salvadoran family I met canvassing in Wheaton, Maryland, highlighted sensitivities around this. The wife shared how she and her husband immigrated over 25 years ago. The husband provided for their family these years by pouring cement in construction.

In the classic immigrant story, both daughters were now better educated than their parents: the eldest was teaching high school while the youngest was studying to be a doctor. She was rightly proud of her family’s success in America. She noted that they voted Democratic, but that those “not immigrating the right way” – as they’d done – “but trying to jump the line” offended them and made them question supporting Democrats.

Tensions are palpable in some suburban communities. You can sense this in neighbourhoods where only one group is displaying yard signs. It’s encouraging when signs proclaiming “Trump, Low Prices, Kamala, High Prices,” “Felon 2024,” or “The Outlaw and the Hillbilly” are interspersed with signs opining “Hate Never Made America Great,” “Trump is a Scab,” or “Dump Trump.”

When signs aren’t displayed in people’s yards, but are instead placed in public spaces along roads or at intersections, you wonder if some intimidation might be under way.

A life-long female Democratic voter told me in Levittown, Pennsylvania, that she wouldn’t put up any form of support for the Democratic ticket. She felt certain that any signs would immediately get destroyed in her neighbourhood, adding that no fellow Democrats felt it was safe to do so. Some really feared being “outed” as a Democrat. She also speculated (correctly) that I wasn’t from that neighbourhood, remarking, “you’d only canvass here as a Democrat if you weren’t from here.”

Loud and proud Trumpers mixed with private but defiant Democrats – and vice versa – make for fraying and distrustful communities.

Two female Democratic voters on my canvassing list in Bensalem, Pennsylvania, lived on either side of a home with a very large Trump flag splayed across its back fence. One woman shared that she’d lived next to the Trump couple for 20 years. She’d been shocked when he’d put up a small pro-Trump yard sign in the 2020 presidential election. And when this huge banner went up recently, something changed for her. She wondered if she’d feel comfortable turning to him for help if, say, her husband was away and she discovered she had a flat tyre.

Politically mixed neighbourhoods are becoming rarer as America increasingly sorts itself into echo chambers where people live and communicate only with those who think like they do. Yet many Americans still enjoy the cosy proximity of diverse neighbours.

At the Pennsylvania home of a young family where both parents were strong Democrats, a pack of children was playing. The father shared that, among the children at his home that day, were the children of his immediate neighbours who had multiple Trump signs on their front lawn.

Another child inside was from the family across the street where the father apparently voted one way and the mother another. He said the parents also socialised together. He described how his family had dined recently at the home of the strident Trump supporters and how they “just avoided speaking about politics” when they got together.

Like in South Africa, Americans have to figure out coexistence and tolerance – despite different political viewpoints. Hopefully, on 5 November, Americans will set aside their apathy, disillusionment and cynicism to vote in peaceful and considered elections where all vote their consciences without fear and intimidation.

Months of canvassing for these elections have left me utterly uncertain about which way a majority of Americans will vote. DM

Micheline Tusenius, a dual citizen of South Africa and the United States, is a writer living in Washington, DC.