Wilderness trail guide Rodney Hlatshwayo and his colleagues have taken some bigshots into the Zululand bush over the years: business tycoons, political leaders and even royalty.

Occasionally they get asked if a certain guest might receive VIP treatment. “But how do you do that?” asks Rodney. “Here we are all the same.”

His is a commentary as much on how the practicalities of the trail preclude pampering, as it is on how time spent in what is an untamed corner of KwaZulu-Natal’s Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, reduces things to their essentials: prince or plebeian, out there it’s just you and nature.

Which is not to suggest we were travelling light when we entered the wilderness, at least not in the physical sense. We had parked our minibus at the trailhead and set about stuffing our backpacks with food for four nights and the means to cook it. Along with clothes and camping gear, we had to find space for a couple of big pots and kettles. Spoons had to be separated from cups lest clinking signalled our approach to wild animals.

With the camera on timer, our little group gathers for a group pic above the Black Umfolozi River on the final day of the trail. From left are Josh, a Cape Town-based American, old friends Kenny and JP from Johannesburg, Gabbi, also from Cape Town, Matthew and Cathy from Durban, and our guides, Rodney and Njabulo. (Photo: Camera on timer)

With the camera on timer, our little group gathers for a group pic above the Black Umfolozi River on the final day of the trail. From left are Josh, a Cape Town-based American, old friends Kenny and JP from Johannesburg, Gabbi, also from Cape Town, Matthew and Cathy from Durban, and our guides, Rodney and Njabulo. (Photo: Camera on timer)

Then, as a lone impala looked on, we set off in single file.

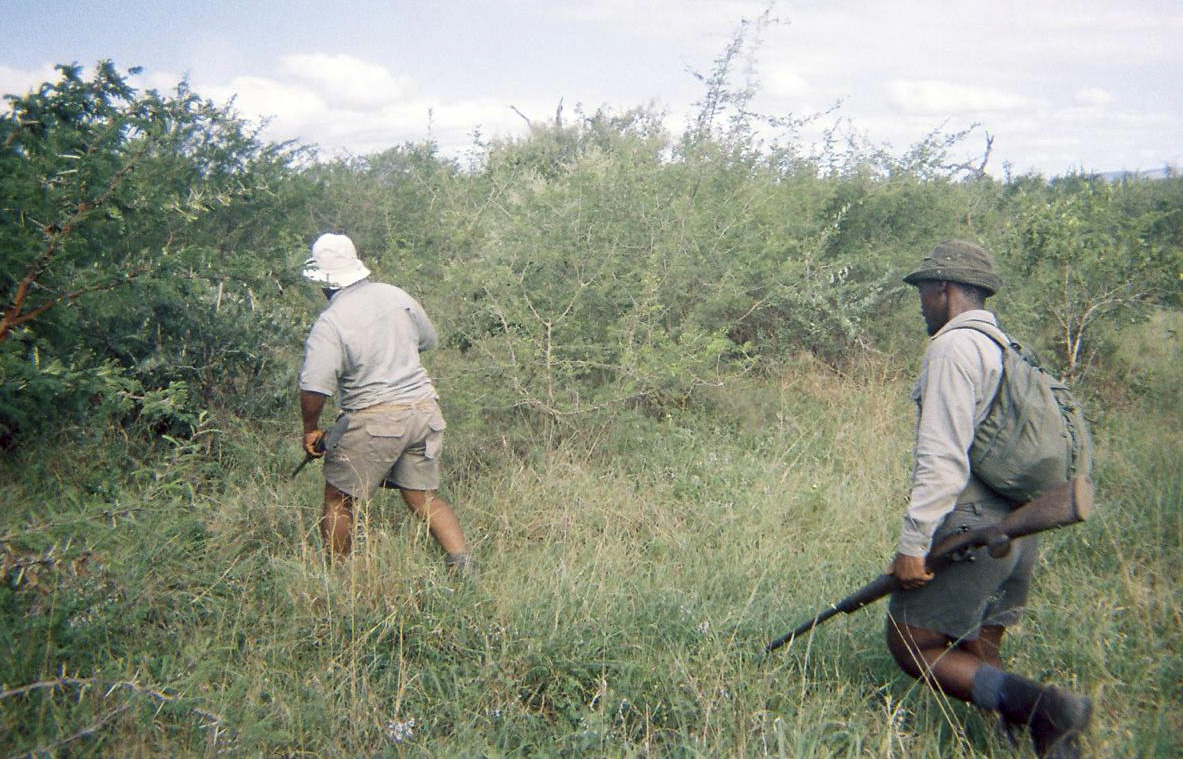

Rodney and fellow guide Njabulo Ngwazi led the way, rifles in hand, ready to come between us and any danger. A short while later our guides called a halt. We gathered as Rodney reminded us, six city folk from Durban, Cape Town and Johnannesburg, to keep quiet and stay alert.

We must be ready to jettison our packs and flee, climb or hide behind trees, depending on what comes our way.

A genial man with an easy authority and a Shembe’s beard and generous head of hair, Rodney told us we were leaving behind the workaday world and crossing into a sacred place. He reminded us how some of the world’s great spiritual figures, including John the Baptist and Muhammad, went into the wilderness seeking enlightenment. As it happened, we were beginning our journey on Good Friday, the culmination of Christ’s ministry, which began after 40 days in the desert.

Ian Player

The Wilderness Leadership School, which runs the trail, was founded in 1957 by the late Dr Ian Player, the celebrated conservationist.

Player, who with his friend and mentor Magqubu Ntombela took hundreds of men and women into Hluhluwe-iMfolozi, came to realise that when we spend time in the wilderness, free of the trapping of our everyday lives, the effects can be therapeutic, inspiring and sometimes profoundly spiritual.

Our spirits rise as we set off from the Black Umfolozi on a bright autumn morning. Although we were aware that danger might be lurking around the bend, the overwhelming feeling was one of peace. (Photo: Matthew Hattingh)

Our spirits rise as we set off from the Black Umfolozi on a bright autumn morning. Although we were aware that danger might be lurking around the bend, the overwhelming feeling was one of peace. (Photo: Matthew Hattingh)

A seeker after truths in his own right, Player was enamoured with the philosophies of Carl Jung and the idea that we need to journey into our personal “inner wilderness” to discover purpose and meaning. Time spent in wild spaces helps us to achieve this as we reconnect with nature, discover an environmental conscience and perhaps one day lead others on the same path

This remains very much what the school and its trails are about.

Excess baggage

Shouldering our backpacks we continued on our way, following animal paths through dense bush. After perhaps half an hour of watchfulness and walking we paused under some sycamore fig trees.

It was here, said Rodney, that Player and his companions would sometimes bury their sleeping bags to lighten the load when out walking.

In 1984 when Cyclone Demonia struck, its floodwaters carried away their kit. It also laid waste to the bush in this spot, but you wouldn’t know to see it now: it’s all grown back. There’s a timeless quality about the place that brings perspective; it helps rid you of excess baggage.

Further on, our guides pointed out a rhino grazing on higher ground, above a bend in the Black Umfolozi River. Rodney set us on a course that took us down towards the river, out-flanking the rhino before it might have thoughts of coming between us and the water. Then we walked through some reeds, passed beneath tall sycamore figs and finally clambered over a few rocks near the river’s edge.

Gag

“Home sweet home,” said Rodney as we arrived at our campsite. “Here’s the kitchen. Put the (fire) wood down,” he said, gesturing to a flat expanse of rock. “Here’s the first bedroom and here’s the second,” he said, indicating a wide, stony ledge above the first.

The concierge gag was probably an old one, but Rodney played it with a light touch.

Pausing to reflect as the sun slips behind Mpila hill, seen from a campsite above the Black Umfolozi River. (Photo: Matthew Hattingh)

Pausing to reflect as the sun slips behind Mpila hill, seen from a campsite above the Black Umfolozi River. (Photo: Matthew Hattingh)

Our rocky kitchens and bedrooms rested a few metres above the river, the drop to the water almost sheer. Above us, the ground was precipitous. The only viable approaches to our camp were the path we came in on, or with more difficulty, along the high bank downstream.

Across the river, opposite us, a single buffalo stood on a stretch of sand, chewing the cud. It had an air of general indifference. It didn’t give a tinker’s that our guides had picked us such a scenic spot, or that our campsite provided natural protection from predators.

Crocodile rock

The sun would soon be sinking behind Mpila Hill and Goqo. There was work to be done.

To draw water, a camping bucket was lowered into the river on a length of rope – a precaution against crocodiles. Rodney explained that while most wild animals, unfamiliar with man, attacked only in self-defence, this didn’t apply to crocs, who were opportunistic, aggressive hunters.

Elephant dung feeds new life. (Photo: Matthew Hattingh)

Elephant dung feeds new life. (Photo: Matthew Hattingh)

But if eternal vigilance is the price we pay for liberty, sometimes we need reminding of it, as Rodney would do a couple of days later when he spotted Cathy, from Durban, dangling her legs above a different stretch of the river. We had been taking turns showering, relishing the wonderful tonic of a bucket of cool river water tipped over the head after a hot afternoon’s walking.

But on that first day, our group was still finding its feet. So, when the first bucket came up from the river, brimming with an unappetising brown liquid there was rather less enthusiasm.

Gabbi, a sweet Cape Town artist, looked doubtful, but brightened when a few sachets of purifier turned it clear.

Fire was another necessity and Rodney and Njabulo set to work with the firewood we had gathered en route. They also busied themselves turning the chicken and veg from our backpacks into a tasty meal.

Night watch

After dinner Rodney briefed us on keeping watch. While the guides slept the guests would take turns tending the fire, a vital deterrent to predators.

From time to time, whoever was on watch had to shine Rodney’s powerful torch down the path and into the bush, looking out for big cats, hyenas and elephants.

For our amusement he suggested we scan the river’s opposite bank for animals safely beyond reach, or pick out the eerie red or yellow glow of crocodile eyes… now gliding away downstream… now swimming silently towards our sleeping party.

The nightly watches proved both a burden and a blessing. It took hot tea and some effort to shake off sleep when it was your turn to get up, but it was also a time for thinking, a chance to enjoy some solitude while taking in the calls of the wild at night.

A rhino and her sub-adult calf close to our picnic spot. (Photo: Matthew Hattingh)

A rhino and her sub-adult calf close to our picnic spot. (Photo: Matthew Hattingh)

But hang on a moment Rodney, wristwatches, cellphones and the like are not allowed on the trail, how do we know when our hour-and-a-half watch is done?

He told us to pick a star and follow its passage through the heavens. When it had moved a hand-width an hour would have passed.

Ok, that’s fine Rodney, but it’s cloudy; what to do?

“Use your intuition,” advised our Buddah of the Bush, who at other times on the trail would deflect the daft or insoluble questions we threw at him with a smile or a gnomic: “What do you think?”

Apart from complicating timekeeping, the clouds on the first night brought other troubles. We had barely settled down when it began raining.

Those of us who had elected to sleep under the stars were suddenly wrestling tent poles in the dark. Cathy announced in a stage whisper that I was “useless” and our bickering provided light relief to Gabbi and Josh who were also scrambling to pitch their tent below us in the first bedroom.

No rush

We awoke next day to the sight of two bull elephants browsing on the same hillside where we had seen the lone rhino. The elephants were in no hurry to move on, but we newcomers to Imfolozi were still adjusting to the pace of the place.

After a breakfast of muesli, tea and coffee, most of us were stuffing our packs and raring to go. Rodney couldn’t see the rush, though. And soon enough we understood why when it began to rain and the order went out to pitch tents.

No sense in hurrying off to nowhere in particular, only to get drenched.

The Wilderness Trail is not a hike, a safari, or an endurance event, the organisers will tell you.

The quest is for something else, with time set aside for meditating or journaling.

I remember perching on a high rock under a tree and with nothing but my thoughts for company, watching as European swallows zig-zagged above the Umfolozi, almost skimming the water as they harried after insects.

At other times our little group would gather (on one occasion passing around a talking stick) to share whatever was on our minds, but mostly how we felt about the place and the sense of gratitude, clarity and direction it seemed to bring.

Rodney, who has been guiding in Imfolozi for 18 years, and Njabulo, a younger man who was born and lives in the Kenneth Stainbank Nature Reserve, in south Durban, set the tone in these talks, speaking about the healing they experienced and the growing connections they felt with the wild animals around us and the bush.

On one of the days they invited us to leave our heavy packs behind at camp and walk unencumbered through the bush, free to ask questions.

Rodney would stop every now and then for a lively show and tell.

Industrious scarabs

He pointed out a white rhino midden – the personal outhouse of one of these outsized, very territorial herbivores.

Before our eyes, the midden was stirring. Dung beetles were on the job, collecting and feeding on rhino faeces.

The hungry and industrious scarabs attract francolins and monitor lizards, Rodney said, going down on his haunches and wriggling his rump and shoulders from side to side in what I thought was a very passable imitation of a monitor lizard.

The lizards and francolins in turn draw eagles. And so the circle of life goes round.

Rodney’s affinity with the bush and its creatures, his wry observations and stories about his own life (from lodge maintenance worker, to trail guide, to community activist, and recently would-be parliamentarian) had us rapt. So much so that Josh, an irrepressible American Capetonian with a rapid-fire sense of humour, took to addressing our leader as “King Rodney” – and not entirely in jest.

Njabulo was generous with his knowledge and attention, too.

In the distance, buffalo on the banks of the Black Umfolozi. (Photo: Matthew Hattingh)

In the distance, buffalo on the banks of the Black Umfolozi. (Photo: Matthew Hattingh)

He showed us a buffalo thorn or umphafa tree. “Very, very important to us.” In Zulu culture, he explained, when someone dies a branch from the tree could be broken off and used to transport his spirit home. “If you travel by taxi, just be sure to stop whenever you reach a river and reassure the spirit. Once home part of the branch may be offered to a goat, and part goes to the homestead’s sacred house, or it’s put on the rooftop.”

The buffalo thorn was not only a source of food for rhino, but provided a thorny redoubt from where thick-skinned buffalo could resist lions.

It was also traditionally used to treat headaches, said Njabulo.

We paused to look at a bushman’s tea tree (the leaves are used to treat flu and to wash one’s hands after a funeral); we examined some finely processed buffalo dung (it’s a ruminant, you see); admired a hyena paw print; sniffed at some wild basil; and marvelled at a termite nest with all its wonderful goings-on beneath the ground. Njabulo told us of the tireless grass-harvesting termite workers, soldiers and their fecund queen, capable of laying 30 000 eggs in a single day.

Poachers

On a number of occasions we heard the drone of an approaching light aircraft and watched as it passed overhead, hunting for poachers.

Last year Hluhluwe-iMfolozi bore the brunt of a national increase in rhino poaching. According to official figures released in February, 499 rhinos were poached across South Africa in 2023, compared with 448 in the previous year. Of the rhinos killed in 2023, 307 were in the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) provincial park.

Kruger, the only national reserve where rhino were poached, recorded a 37% decrease in poaching compared with 2022, with a total of 78 poached in 2023.

Many years ago Player led ground-breaking efforts to capture and relocate white rhinos from iMfolozi to restock other parks, including Kruger where the last remaining white rhino had been shot in the 1890s, doing much to save the animal from extinction. Now it’s Hluhluwe-iMfolozi that needs help as criminal syndicates, feeding a multibillion-dollar hunger for rhino horn in the Far East, have set their sights on KZN’s rhinos.

In 2021, poachers killed a total of 102 rhinos in the province; 244 in 2022 and 325 last year.

At the release of the 2024 figures, the then environment minister Barbara Creecy spoke of “relentless pressure” from poaching and of efforts to stem it.

Kudu voodoo

On day three we walked away from the river. On a ridge a few hundred metres to our east, our guides spotted giraffes. Such is their natural camouflage that even with binoculars it’s hard to see them until they move.

We headed in the general direction of the giraffes, startling a few kudu in thick bush near the path, before climbing a slope towards a stand of tamboti trees at the top.

Downwind, beyond the trees, next to a mudhole, stood a rhino and her teenage calf. They were perhaps 50m from us.

Gabbi tends the fire. Our group took turns at night keeping watch for unwanted visitors. (Photo: Gabriella Sexwale)

Gabbi tends the fire. Our group took turns at night keeping watch for unwanted visitors. (Photo: Gabriella Sexwale)

We spread out our things in the shade and spent a couple of hours picnicking, chatting over chilli-laced sandwiches of cheese and cold meat, enjoying each other’s company and the pleasure of having the rhinos so near.

Rodney said he guessed rhinos might be about when he heard the cry of a red-billed oxpecker as we neared the trees. The birds famously warn the big mammals (like poor-sighted rhinos) whose ticks they feed on, of approaching danger.

Njabulo told us how when ticks trouble a wildebeest or zebra they roll in the dust to shed the parasites.

Lots of rolling in the same place by still more animals scours away any remaining grass, leaving a depression, where in time water collects.

One day a warthog will wander by. It will roll in the mud and so the depression will gradually grow bigger. Eventually buffalo and rhino will come along. Maybe a rhino and its calf will find a place to cool off too.

In the wilderness each thing has its time and place, everything its season. The circle of life turns round. And so it goes… unto dust. DM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REeWvTRUpMk

Gabbi tends the fire. Our group took turns at night keeping watch for unwanted visitors. (Photo: Gabriella Sexwale)

Gabbi tends the fire. Our group took turns at night keeping watch for unwanted visitors. (Photo: Gabriella Sexwale)