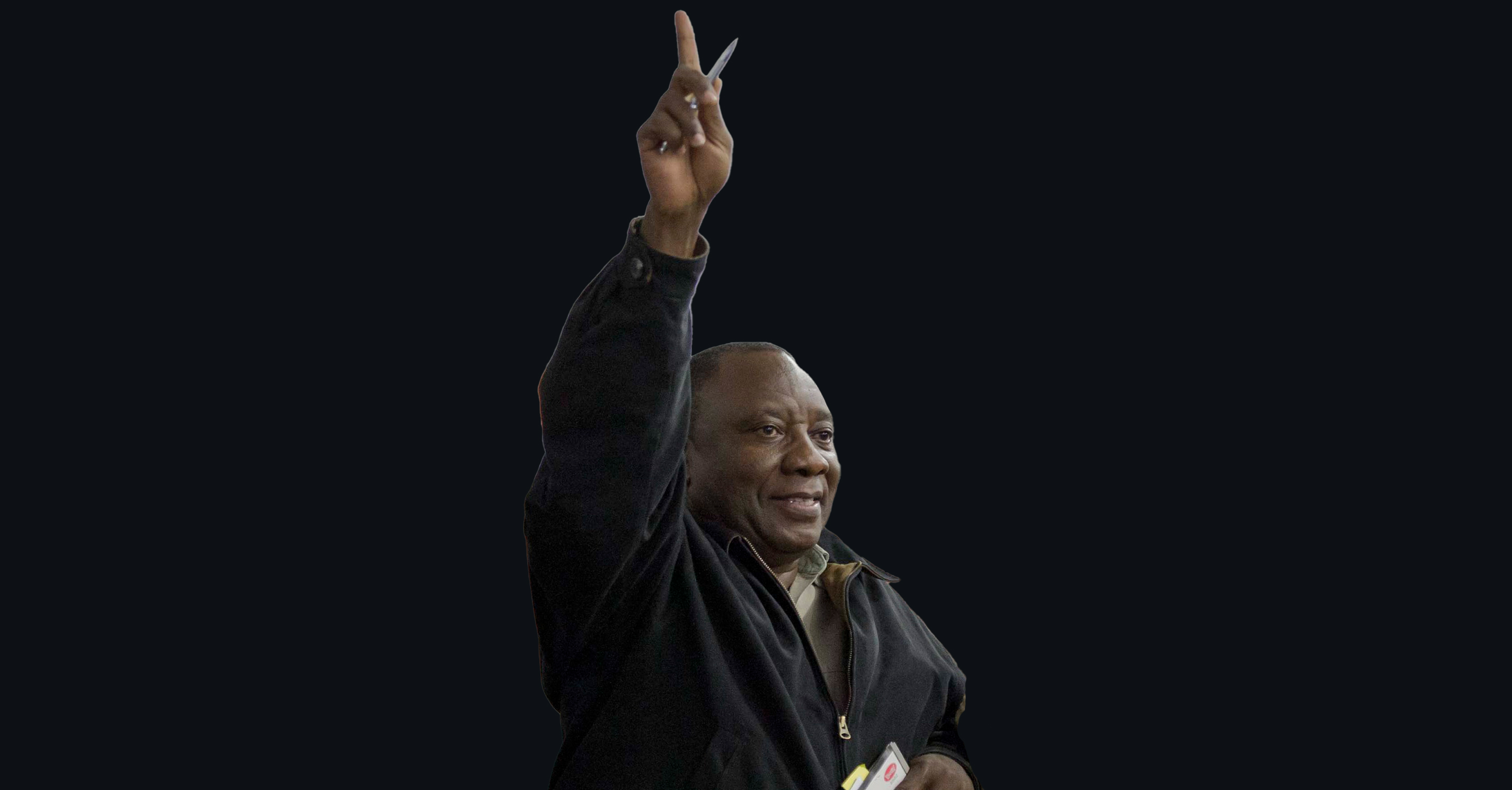

Have you seen Cyril Ramaphosa lately? The man looks like the proud grandparent of a R12-million Oryx calf. He resembles a convict unexpectedly released from solitary confinement, who now inhabits the penthouse suite in a seven-star Dubai hotel. Once he was a rusted 1987 Datsun, he is now reincarnated as a Maybach.

Indeed, the ashen presence who stared with glazed eyes at an iPad over the course of his first term is now plumper, his colour richer. He laughs readily, and has defaulted to the back-slapping bonhomie of his billionaire businessman era. From 2019 to mid-2024 he was a glitchy, low-res picture taken on a flip phone. Now, he’s a film clip taken on an iPhone 16 Max Pro.

What has changed Ramaphosa’s comportment so drastically?

In short, he lost an election.

For most politicians, being thrashed as thoroughly as Ramaphosa was in June would be the low point in a career of low points, a humiliating tumble that even the sharpest analysts failed to anticipate. The ANC tumbled from 57.5% to 40.18% in the space of one election cycle, and lost the parliamentary majority they’d enjoyed since the advent of local franchise.

This being South Africa, Ramaphosa wasn’t fired for this felonious act of political malpractice. Instead, he said some nice words about democracy, and implied that the ANC should be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for being the rare liberation party not to burn the country down after an election wipeout.

He then went back to his desk and shuffled some papers around.

Meanwhile, Jacob Zuma, Ramaphosa’s old boss, returned from the grave to smash through the ANC’s support in KZN and elsewhere, inadvertently handing Ramaphosa a gift: a huge cohort of really stupid people uselessly inhabiting a chunk of the opposition benches. The MK party came out of nowhere to rule over nothing. There were many dark warnings in the early days of the seventh administration of a “doomsday coalition”— a Tolkien-ish alliance of Orcs that would include the “progressive forces” in the ANC, along with the EFF and Zuma’s MK counter-counterrevolutionaries.

Instead, Ramaphosa assembled what was branded, rather hilariously, a Government of National Unity. (This was meant to evoke the soaring days following the end of apartheid, as if losing an election is some kind of historical accomplishment.) In reality, what Ramaphosa needed was a coalition that loosely stapled his faction of the ANC — let’s call them the “aspirant technocrats”— to a handful of parties that would get him as close to a parliamentary majority as possible.

Glad-handing is Ramaphosa’s superpower. He set about luring the DA, PA, and a bunch of lesser acronyms into his polycule, dangling before them the baubles of cabinetry. In a series of smoky backroom auto-hagiographies, DA Federal Chair Helen Zille stage-whispered to News24 how she and her fellow Bismarckian strategists were able to play the ANC like schoolchildren at a Smartie factory. But when the whole thing flushed out, it was difficult to imagine how anyone had benefited more than Ramaphosa.

He shut down his enemies in the ANC, pacified the opposition, and crafted for himself a best-case government that had no choice but to do its job.

* * *

Is Cyril Ramaphosa some kind of political mastermind, who played the long game for so long that we all forgot it was a game? Or is he simply an example of the one-testicled man in the land of the castrated?

The evidence — of which there is an abundance — is that Ramaphosa stumbles from committee to commission, hoping for the best, inviting the worst, but remains firm in the belief that good things happen to rich people.

Looking back slightly, it cost Ramaphosa and his allies mightily to sway the intra-ANC national elections in 2017. And while it’s tempting to say that he inherited a broken state, the truth is that he helped break it — or, rather, he was so baffled by the situation that he couldn’t do anything other than gawp in shock as the country was dismantled in front of him. His infamous 2014 Eskom “war room” appeared to direct most of its weaponry at Eskom — the place was all but flattened after doses of his consensus-building expertise. It was clear that Ramaphosa did not carry a big stick — he was the political equivalent of an industrial carrot farmer. And it boded ill for his presidency, should the time come.

Well, it did come — and holy Ankole cow was it a mess. We have litigated the awfulness to death, and so we must acknowledge that Ramaphosa’s first term added another five years on to Zuma’s nine wasted years. And if his intentions were as pure as his apologists insisted they were, that makes it even worse. Regardless, call it fourteen years of state and institutional capture, in which a sophisticated and deadly gangster demimonde appended itself to South Africa like a limpet mine. If Zuma used the security apparatus to subvert the state, Ramaphosa needed a state to subvert the security apparatus.

He didn’t have one.

Disgorging an entrenched, established and experienced mafia system is not easy. But one way of keeping the lights on is, well, keeping the lights on. In this, Ramaphosa got very lucky. As Chris Yelland reported in these pages, during the election campaign, Eskom “fixed” itself — because big chunks of the grid were effectively privatised by a citizen-led renewable energy revolution, coupled with a small uptick in efficiency.

Eskom is still laughably broke, but it’s not exactly the existential threat it was prior to the pandemic. And speaking of which, that little episode certainly didn’t help Ramaphosa during his first term. While he was playing dad on TV, he showed his fecklessness by allowing ministers like Nkosozana Dlamini Zuma and Ebrahim Patel to settle into their newly authoritarian briefs by banning the likes of roast chicken, alcohol and cigarettes. The chicken industry has recovered, but the pandemic set free the impulses of a cigarette mafia; their Zimbabwean brethren that has grown so powerful that it almost bought the sugar giant Tongaat-Hulett.

Speaking of organised crime, one thing Ramaphosa failed to do was unleash the Hawks and the National Prosecuting Authority on syndicates within the ruling party. Outside of Zuma avoidably landing himself in jail on contempt of court charges, there hasn’t been any meaningful movement on State Capture prosecutions. Ramaphosa was equally gentle with his real political opponents: Julius Malema and Floyd Shivambu were apparently immune to any consequences for their clear involvement in the VBS bank robbery. The only sap who got defenestrated was Ace Magashule, literally the dirtiest warlord democratic South Africa has ever had.

* * *

Given the scale of the mess, to what must we attribute the current Ramanaissance?

First, the Springboks are undeniably the finest rugby team in the world. This may or may not have anything to do with Ramaphosa, but it keeps the restive white minority sedated on good vibes, and that’s no small thing.

Second, the ANC is committed to ramming home its pet legislation, and Ramaphosa is delivering. In the weeks before the election, he signed the ridiculous (and likely unconstitutional) National Health Insurance bill. This cost the ANC a measurable amount of middle class and business support, but no matter — the internecine ANC war was momentarily quelled, and the argument against his leadership was diminished internally. Next was the so-called Bela education bill, which was "partly" signed despite (or because of?) the loud objections of the DA and FF+, who claimed that it would erode the educational rights of their Afrikaner constituents, among others.

On the foreign policy front, while the ANC has slightly dialled down overt support for Russia following the invasion of Ukraine, it has not moderated its stance on mass murder in the Middle East — it is firmly on the side of the Palestinians, and won’t budge by a millimetre.

And the “economy”? Who knows? Is there a plan? There is! Along with his CEO collaborators, Ramaphosa hopes to create “a million new jobs”. Sounds good. And yet, South Africa remains a post-employment economy. The so-called informal sector is the only possible future outside of Chinese-style factory slave labour, but we have laws here, so the informal economy it is. To make it work will require a universal basic income regime of some description, which is apparently considered “communism” by some members of the coalition.

Any one of these issues should — and still could — rip the coalition apart. But so far, the bleating is not as loud as it might be. Putting John Steenhuisen in kortbroek was a stroke of brilliance — as agriculture minister, he, too, is living his best life. Same goes for the rest of the DA ministers, and for xenophobic bully Gayton McKenzie, who is currently camping it up as a reformed jogger.

Even more felicitously, the deputy president position remains the most poisoned chalice in South African politics. Paul Mashatile is facing a raft of charges, and is likely to be a member of MK in the not too distant future. And perhaps that is the key to this entire mystery. By a mixture of accident, providence and a smidge of design in export of baddies and morons to MK — and by having his ass thoroughly whipped at the polls — Ramaphosa is now the happiest he’s ever been in politics.

There is much that can still go wrong, and even more that certainly will go wrong. In the meantime, give Ramaphosa this much — he made lemonade out of lemons. The squeeze, however, has barely started. When it does, we know how proficient he is at gawping in mute shock. But in the context of South African politics, Ramaphosa has once again proved that the real winners are the losers. DM