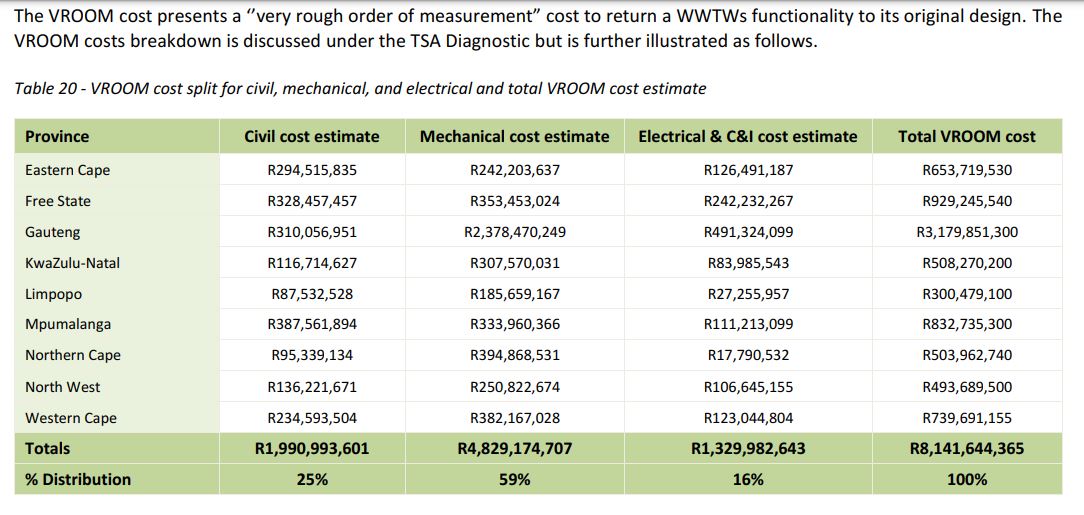

More than 60% of South Africa’s sewage and wastewater treatment works have been officially classified as being in a “poor to critical” state — and the estimated price tag for fixing the shambles is more than R8.14-billion.

Of the 850 plants audited nationwide last year, fewer than 3% were accredited with Green Drop status, which signifies excellence in wastewater treatment and purification.

The Green Drop scheme rates the treatment of polluted water after passing through municipal and private facilities and then being released into rivers, wetlands or the sea. This is entirely separate from the Blue Drop system, which rates the quality of drinking water flowing from municipal taps.

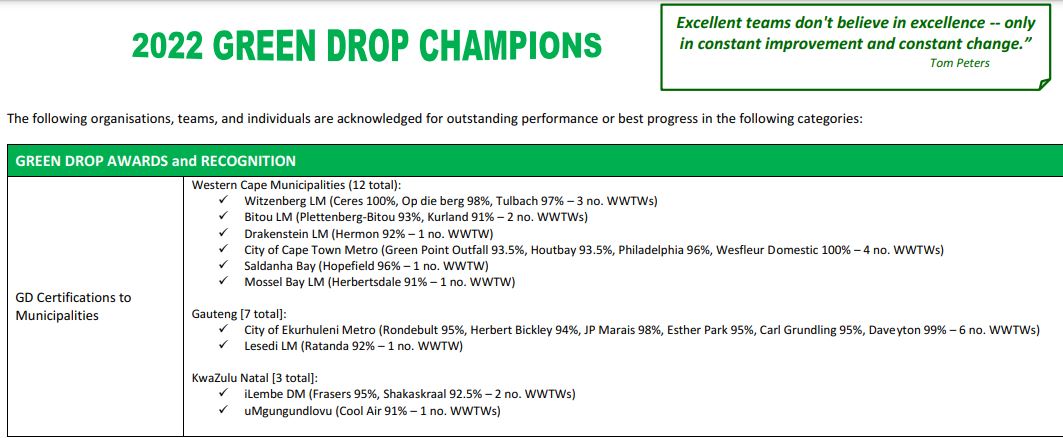

To attain Green Drop status, treatment facilities need to score 90% or higher. They are judged on a variety of weighted criteria which include staff capacity, environmental, financial and technical management issues and compliance with effluent and sludge disposal measures.

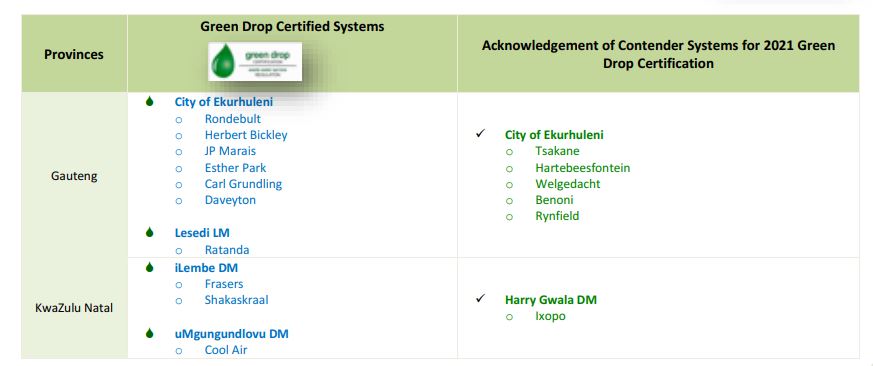

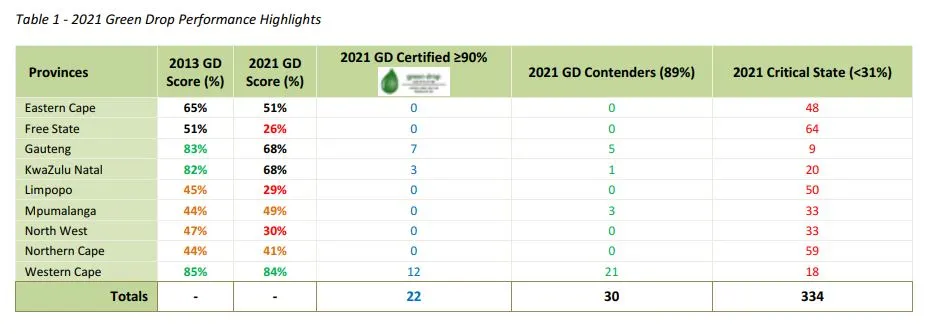

Only 22 facilities (12 in the Western Cape, seven in Gauteng and three in KwaZulu-Natal) were awarded this distinction in the 2022 Green Drop report published this month — the first such report in nine years.

Some passed, most failed

The only big city facilities that managed to pass the test were in Cape Town, along with parts of the East Rand (Ekurhuleni). Overall, the best treatment plants were in the much smaller Witzenberg, Bitou and Drakenstein local municipalities outside Cape Town.

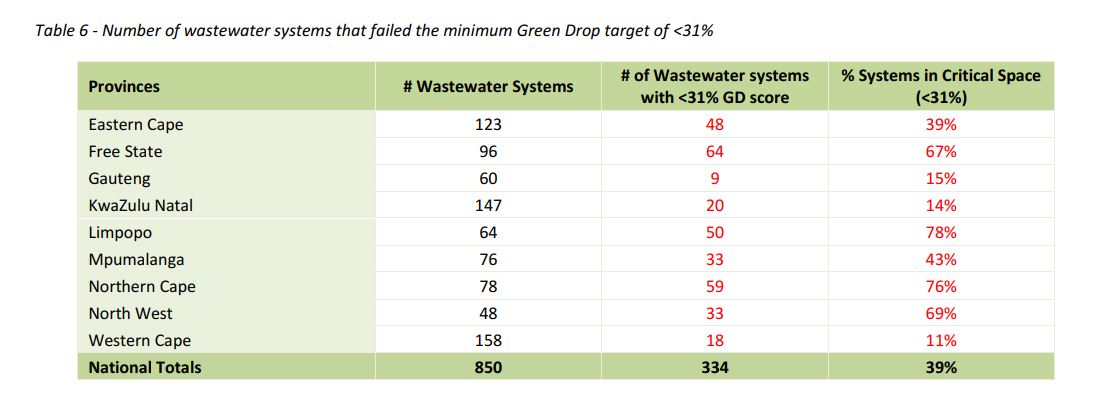

As for the rest, 39% of South Africa’s wastewater treatment plants were classified as being in a “critical state”; 24% in “poor” condition, 22% as “average” and 11% as “good”.

The overall big city Green Drop scores were Cape Town (88%), Ekhurhuleni (86%), eThekwini/Durban (76%), Johannesburg (73%), Tshwane/Pretoria (60%), Buffalo City/East London (61%), Nelson Mandela Bay (58%) and Mangaung/Bloemfontein (33% ).

Recently appointed Water and Sanitation Minister Senzo Mchunu has acknowledged that the report represents a robust and scientific assessment of the “dismal state” of South Africa’s wastewater management systems, and has promised strong action.

Now that the report has been published, the public will be watching closely to see if the government lives up to its promises to fix the mess.

The Organisation Undoing Tax Abuse (Outa) has commended the new ministerial leadership for being “bold enough to publish these facts and committing to action”.

‘Jail municipal managers’

The department now had to walk the talk and set an example by throwing certain municipal managers into jail, said Dr Ferrial Adam, Outa’s water campaign manager.

“We think that he (Mchunu) should go as far as charging municipal managers for sewage pollution under the National Environmental Act. We need all hands on deck to fix these dire problems and one or two municipal managers must go to jail to change the future of sewage management.

Minister of Water and Sanitation Senzo Mchunu. (Photo: Gallo Images / The Times / Jackie Clausen)

Minister of Water and Sanitation Senzo Mchunu. (Photo: Gallo Images / The Times / Jackie Clausen)

“Civil society will play a bigger role than ever to support the change and to expose and hold to account those who negligently pollute our scarce water resources.”

Adam said sewage spillages and failing wastewater treatment works were harming not just the environment, but also the national economy and the livelihoods and health of people.

She suggested that average Green Drop scores often concealed bigger problems.

“For example, Gauteng seems to have only 15% (of plants) in a critical state, but if we look at just the Emfuleni municipality and the sewage spills into the Vaal River, the damage is enormous, as the Vaal provides water to more than 15 million South Africans.”

Mokonyane scrapped Green Drop

The last Green Drop report was published in 2013 and then suspended, largely at the behest of former Water and Sanitation Minister Nomvula Mokonyane because the results were so shocking.

The publication of the latest (equally embarrassing) 2022 Green Drop Report was, however, sanctioned by President Cyril Ramaphosa and Mchunu.

“It remains unacceptable that sewage spillages and failing wastewater treatment works are detrimentally impacting our environment as well as the livelihoods and health of many of our communities on a daily basis in the year 2022,” said Mchunu.

“There is still a mammoth task ahead of us,” he said.

Readers who wade through the full 558-page report will discover just how daunting — and expensive — it would be to turn the situation around.

According to preliminary calculations, the repair bill is expected to be R8,141,644,365 (more than R8.14-billion).

Municipalities in the spotlight

Appealing to the country’s political, public and private leadership to help turn the situation around, Mchunu also brandished a stick, saying, “I need to make it clear that action will be taken against those municipalities that flagrantly put the lives of our people and environment at risk”.

Dr Sean Phillips, the newly appointed Director-General of the Department of Water and Sanitation, said his department would now use the information from the report to guide more effective planning, budgeting and professionalisation of the wastewater sector.

Overall, the latest report tells a story of regression nationwide since the 2013 report.

Just 22 wastewater plants were judged to be excellent over the past year, compared with 60 plants in the last report.

These “excellent” Green Drop plants were operated by the City of Ekurhuleni, City of Cape Town and Sasol, and the district or local municipalities of Lesedi, iLembe, uMgungundlovu, Witzenberg, Bitou, Drakenstein, Saldanha Bay and Mossel Bay.

Another 30 plants narrowly missed 90%, with the vast majority of rural municipalities struggling to score more than 50% — largely due to the absence of specialist engineering and scientific skills in outlying areas.

Several scored 0% (including the Thabazimbi, Ngaka Modiri, Moretele and Mafube municipalities).

Read: Declare South Africa’s wastewater treatment a national disaster, urges SAHRC

System failures

The most prominent risks were seen at the treatment level and pointed to works that exceeded their design capacity, dysfunctional processes and equipment (especially disinfection), along with a lack of flow monitoring and effluent and sludge non-compliance.

Overloaded or dysfunctional treatment works were also a reflection of the growing pressure placed on existing collection and treatment infrastructure driven by population and economic growth.

An aerial view of the Diep River estuary – also known as the Milnerton Lagoon – shows highly polluted blackened water flowing into the ocean at Lagoon Beach in Cape Town, South Africa. This water is polluted by the failure of the wastewater treatment works upstream. Photo: Anonymous, supplied by the Milnerton Central Residents Association

An aerial view of the Diep River estuary – also known as the Milnerton Lagoon – shows highly polluted blackened water flowing into the ocean at Lagoon Beach in Cape Town, South Africa. This water is polluted by the failure of the wastewater treatment works upstream. Photo: Anonymous, supplied by the Milnerton Central Residents Association

Worryingly, auditors who travelled across the country found evidence that “several” municipalities had invested large amounts of money on infrastructure upgrades, extensions and refurbishments — but these systems were still failing the regulatory standards (mostly not meeting effluent quality limits), or not meeting engineering and workmanship standards.

Some had not been commissioned, with the department recommending that donor and funding agencies set up new monitoring processes to check if the design and construction process had followed the work plans and to verify the quality of workmanship.

Another major worry was that during such plant upgrades, some municipalities had taken plants completely out of commission and allowed untreated sewage and wastewater to flow straight into rivers and other watercourses.

In other cases, contractors had pulled out because they had not been paid, “resulting in a prolonged continuance of untreated effluent being discharged to the environment”.

As a result, new directives would be issued to grant managers instructing that no capital project should be approved without a contingency/interim plan to ensure the plant remained operational during upgrades.

Theft and vandalism issues

The auditors also found several cases of vandalism and theft of electrical cables and other equipment, which halted polluted water treatment for extended periods. Yet, very few municipalities had anti-vandalism strategies or contingency plans.

While many of the larger municipalities fared well in terms of technical competencies, most smaller municipalities lacked the necessary technical skills.

The department has recommended that these municipalities improve recruitment processes to ensure that only registered, qualified and competent staff are appointed.

It would also require these facilities to establish new programmes so that qualified, experienced professionals could mentor and coach junior staff.

It was also essential for local governments to measure wastewater flows, especially where plants were overloaded or operating close to design capacity.

“Severe deficiencies” were found at most plants nationwide in monitoring their operational and compliance parameters.

“As an example, anaerobic digestion, which makes up the bulk of sludge treatment (and water reuse opportunities), is poorly monitored and operated at most wastewater treatment works.”

These plants needed to urgently correct failures in the disinfection process which caused poor microbiological quality effluent to be discharged into rivers, dams and oceans.

“This single hazard carries risks of epidemic proportions,” the department warned.

‘Expenditure must be monitored’

Because many plants failed to meet final effluent quality standards, remedial action would have to be taken beyond the immediate point of discharge and extend to restoring polluted water bodies, groundwater and soil.

Most municipalities were also failing to plan properly, as “the majority of institutions could not present completed and verifiable evidence in the form of budgets, expenditure, asset values and production cost (rand/m3 treated)”.

Read: South Africa’s rivers of sewage: More than half of SA’s treatment works are failing

As the national regulator of water quality, the department should work more closely with financial sector partners to ring-fence and monitor budgets and expenditure for wastewater systems.

The department should also “engage fund managers and (municipalities) in cases highlighted in this report, where vast amounts of capital funds (mostly grants) have been expended without positive outcomes or impact”.

Sewage overflowing into the Nahoon Estuary in the Eastern Cape. (Photos: Supplied)

Sewage overflowing into the Nahoon Estuary in the Eastern Cape. (Photos: Supplied)

Though the individual culprits are not named in the report, the department said it was looking at a “more drastic approach” towards local governments responsible for significant environmental damage over extended periods.

This could include rehabilitating damaged environments and sending the ecological clean-up and repair bill to the culprits.

The department has warned the private sector that its water treatment plants will also come under stricter focus as the Green Drop Certification programme would become mandatory for all treatment systems (no date specified). DM/OBP

[hearken id="daily-maverick/9317"]

Sewage overflowing into the Nahoon Estuary in the Eastern Cape. (Photos: Supplied)

Sewage overflowing into the Nahoon Estuary in the Eastern Cape. (Photos: Supplied)